![]()

![]()

Copyright © 2022 Chidiogo Akunyili

Published in Canada in 2022 and the USA in 2022 by House of Anansi Press Inc.

www.houseofanansi.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

House of Anansi Press is a Global Certified Accessible™ (GCA by Benetech) publisher. The ebook version of this book meets stringent accessibility standards and is available to students and readers with print disabilities.

26 25 24 23 22 1 2 3 4 5

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: I am because we are : an African mother’s fight for the soul of a nation / Chidiogo Akunyili-Parr.

Names: Akunyili-Parr, Chidiogo, author.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 2021027929X | Canadiana (ebook) 20210279346 | ISBN 9781487009632 (softcover) | ISBN 9781487009649 (EPUB)

Subjects: LCSH: Akunyili, Dora N. | LCSH: Akunyili, Dora N—Family. | LCSH: Women cabinet officers—Nigeria—Biography. | LCSH: Cabinet officers—Nigeria—Biography. | LCSH: Nigeria—Politics and government—1993-2007. | LCSH: Nigeria—Politics and government—2007- | LCSH: Nigeria—Social conditions—1960- | LCGFT: Biographies.

Classification: LCC DT515.83.A38 A78 2022 | DDC 966.905092—dc23

Cover design: Alysia Shewchuk

Text design and typesetting: Lucia Kim

House of Anansi Press respectfully acknowledges that the land on which we operate is the Traditional Territory of many Nations, including the Anishinabeg, the Wendat, and the Haudenosaunee. It is also the Treaty Lands of the Mississaugas of the Credit.

We acknowledge for their financial support of our publishing program the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Government of Canada.

![]()

![]()

“Dora Akunyili was like an elephant. Describing her or telling about her is like asking several blind men to describe an elephant. The descriptions one will hear will be as varied as the number of blind men describing it from how it feels to their touch. Depending on where the man is standing and what he is touching, the elephant can be soft, hard, spiky, scaly, bristly, rough, smooth, fat, slim, floppy, flabby, long, short, wet, dry, et cetera.

No one can really say they know Dora and can comprehensively describe her or talk about her. She was an enigma. She had varied sides to her. She was very good and very bad. She was very kind and could be unkind. She could be generously generous and some would say she was very stingy. She was very humble and some would say she was arrogant and brash. Some would say she was ruthless, some say adorable. Strict disciplinarian, ordered, organized, focused, ambitious, determined, go-getter, achiever. No one can exhaust all the epithets that can describe Dora. Is she indescribable?”

— Iyom Josephine Anenih, Former Minister of Women Affairs of Nigeria

![]()

“Dora Akunyili once thrust a rosary into my hand.

‘Keep it with you at all times to protect you, because success brings envy,’ she said, and added, as though to brook no argument, ‘It was blessed in Rome.’

A slate-coloured rosary with a shiny crucifix. I have kept it since, part comforting superstition and part tribute to a woman who was one of the best public servants Nigeria has ever had.

As the director general of NAFDAC, the food and drug regulating agency, she fought the importers of fake medicines and the makers of unsafe foods, unnerving business interests that had long been complacent in their corruption. They went after her, and she survived assassination attempts; a bullet once narrowly missed her head, striking her ichafu. She was radical because she had integrity in a system that was unfamiliar with integrity. A businessman once told me that Dora Akunyili was the only public official he respected. ‘She smiles with you but she will insist that you do the right thing,’ he said.

She was kind and vigorous, and when she spoke, she widened eyes as though to better convey the force of her conviction.

Nigeria lost one of its best when she died.”

— Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Author

![]()

Prologue: Chidiogo

“Ugogbe — mirror.”

A friend once suggested that I would only be able to tell my mother’s story once I had the experience of being a mother. It turned out that she was half-right. It took me losing a pregnancy to connect fully to the story of my mother, Dora Akunyili.

After my husband and I learned that our nine-week-old baby showed signs of incompatibility with life, I reached out to my father. “Ndo, sorry,” he comforted me. “Even Mummy too experience loss with pregnancy ya,” he said, speaking in a stylized Engiligbo. It was the first I had ever heard of this, and even more shocking was learning that such a loss had happened not once, not twice, but three times, with the third occurring right before she had me. Worried I had somehow missed such an important story, I inquired with all five of my siblings, none of whom knew. In sharing details of bleedings and operations, my father shared as well the tears that accompanied each experience. Yet, for all those years, she kept it to herself. Perhaps it was true to her personality — her ability to move through difficulty with learned ease, sweeping pain away like dust under a dark stairwell — or maybe it was because of the social stigma surrounding miscarriages, which compels women to mourn in silence.

In the weeks that followed, as my husband and I navigated the path of letting go, I experienced such dense pain marked by a mix of sadness, rage, and complete dejection, which, at its lowest point, called for a completely different texture of strength: a softness that required me to fully acknowledge pain’s powerful embrace. I had to learn to recognize and reject anger as my mask, as even the slightest things got me into a fit of violent wrath, trusting that, with time, all would be well, and that it was okay not to feel like my usual self — in control, unflinching.

In control was how I had seen my mother approach even the most challenging situations. It was one of her greatest teachings. Now I was searching for the right fit for my skin.

I wondered about my mother’s pain — that which she carried and that which she buried. The ache of leaving home at such an early age; of living through a devastating civil war, followed by the loss of those she loved the most. This all happened to a girl still in her teenage years. And just when life seemed to offer her a break, a different pain awaited her. By then she had learned to transform her disappointment into unshakable strength, which served her in battle against forces contributing to senseless human suffering across her beloved homeland, Nigeria.

What happens to pain over time when it’s consigned to silence?

As I wrote my mother’s story as if in her own voice, weaving its complex textures into a narrative, I found that her strength was far more apparent than her pain. On the journey of piecing together her truth, I discovered that strength and pain are mirrors of one another, for strength grows to protect from pain, and pain builds strength.

My mother’s legendary brand of strength did not allow for her to linger on that which was not as she desired; rather, she fought for that which was within her control. To this, she gave everything, trusting in her own capacity and the guidance that fuelled her fire. In her last public words, she said, “A society grows great when old men plant trees whose shade they know they shall never sit in.” Therein was her truth: the belief and trust that she mattered, that we all matter, and that our actions have the potential to reverberate through time and space. As she saw it, it was in the best interest of our shared destinies to act in selfless dedication to truth and to one another.

This commitment to supporting each other, leveraging the power of unity, was shaped by her own experiences of how far people can go when they do just this, and it was reinforced by her strong Catholic faith and the Bible’s teachings of the virtues of love and charity, especially for those most in need. This belief is captured by the humanist African philosophy of Ubuntu, which is also a personal guiding philosophy of mine. Ubuntu, which has its roots in the Zulu language, and its branches across various African communities, is an ideology of the universal brotherhood and sisterhood of all humankind, upholding and celebrating our co-dependent human community: “I am because we are.”

It was her focus on compassion that allowed her to transform her pain into support for so many others in their times of need — an unspoken conviction that another’s healing was her own. I experienced this interconnectedness and transference for myself: recovering from my loss, and simultaneously grieving the loss of my mother as if for the first time, I connected even more deeply to the invitation to tell my mother’s story.

While the world saw Dora Akunyili, known by many as the Amazon, at the peak of her strength — a warrior with a gap-toothed smile whose light-skinned oval face was crowned with a colourful head-tie that doubled as armour against incessant attacks against her values — I saw the complexity that was hidden from sight. This is the story of her multiplicity: the story of my mother.

![]()

![]()

![]()

One

“A name is both a prayer and a story.”

I was six, my thick, tight coils in neat plaits, my bright face accentuated by my fair complexion, and my mind mature enough to understand that something major was happening.

In the late 1950s and early ’60s, in the face of Nigeria’s transitions, Papa would explain to me the history of colonization and that hitherto the country hadn’t been free. With this, he often reminded me of the transient nature of things — one moment we were a part of Great Britain and with the stroke of a pen we were not. He underscored his message with his experiences and the drastic changes in his own life, having gone from riches to penury after his father’s death and then again to riches in Makurdi as a business tycoon. He always returned to the emphatic reminder that no one knew tomorrow and as such nothing was to be taken for granted.

He loved to talk about change as captured by history and the passage of time. He spoke of Igbos and the great traditions that had shaped the people, like the very language itself. In the Igbo culture of southeastern Nigeria, he said, the power of words has always mattered, for words form stories, and stories shape mindset and reality.

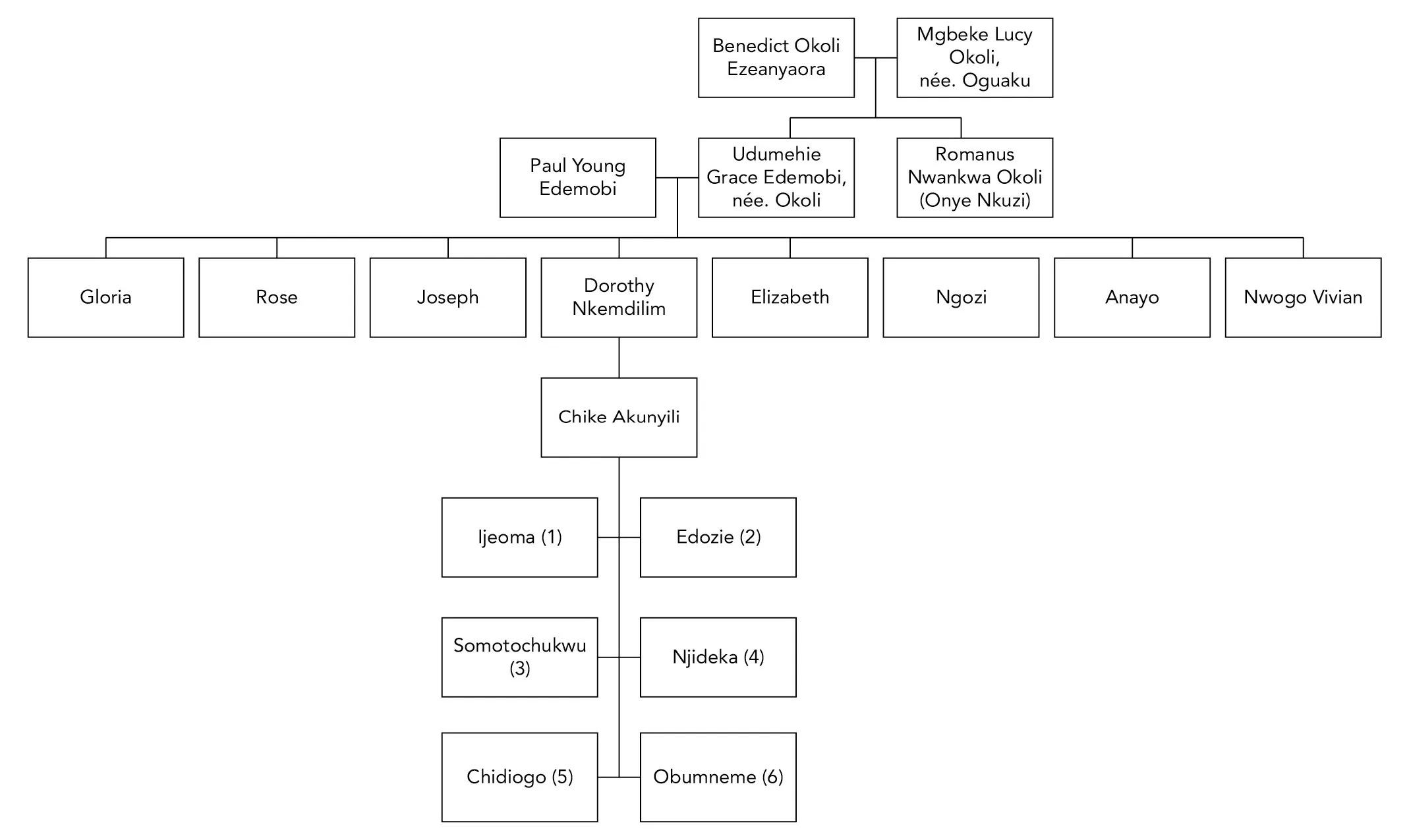

When I was born in 1954, a kola nut was broken in honour of my birth, and isee — “and so it is” — was chorused along with prayers for a long and prosperous life. To support these prayers to take root, I was given the name Dorothy Nkemdilim Edemobi. Dorothy means “gift of God,” and Nkemdilim, “let what is mine be unto me”; in other words, “may my destiny be fulfilled.” Edemobi is short for edeimobi, meaning “I rest my soul.” My name in full was the prayer for the “gift of God whose destiny will be fulfilled so that I may rest my soul” — a heavy name for a newborn girl.

Papa was a great storyteller and he loved to share details of my birth. “One look in your eyes,” he said, “and I knew you were special.”

Some children are drawn to a toy or a blanket; I was attached to my father. I loved to be around him, and I always sought out his presence and drank it in fully.

The affection was mutual. I was the fourth born of eight, but Papa lavished me with his attention. He insisted it was because I was very intelligent; I suspected that it was because I loved listening to his stories the most.

He liked to sit outside on the back porch of our home in Makurdi on the south bank of the Benue River, watching the day slowly turn to night, swatting away mosquitoes as we both listened to the sound of birds overhead saying good night to the day that was. It was his quiet t...