- 757 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

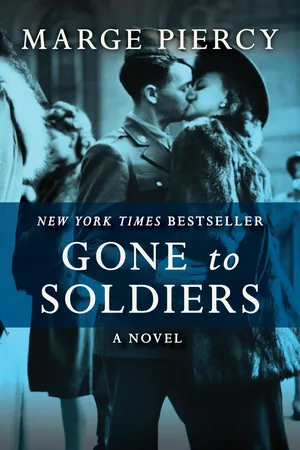

This sweeping

New York Times bestseller is "the most thorough and most captivating, most engrossing novel ever written about World War II" (

Los Angeles Times).

Epic in scope, Marge Piercy's sweeping novel encompasses the wide range of people and places marked by the Second World War. Each of her ten narrators has a unique and compelling story that powerfully depicts his or her personality, desires, and fears. Special attention is given to the women of the war effort, like Bernice, who rebels against her domineering father to become a fighter pilot, and Naomi, a Parisian Jew sent to live with relatives in Detroit, whose twin sister, Jacqueline—still in France—joins the resistance against Nazi rule.

The horrors of the concentration camps; the heroism of soldiers on the beaches of Okinawa, the skies above London, and the seas of the Mediterranean; the brilliance of code breakers; and the resilience of families waiting for the return of sons, brothers, and fathers are all conveyed through powerful, poignant prose that resonates beyond the page. Gone to Soldiers is a testament to the ordinary people, with their flaws and inner strife, who rose to defend liberty during the most extraordinary times.

Epic in scope, Marge Piercy's sweeping novel encompasses the wide range of people and places marked by the Second World War. Each of her ten narrators has a unique and compelling story that powerfully depicts his or her personality, desires, and fears. Special attention is given to the women of the war effort, like Bernice, who rebels against her domineering father to become a fighter pilot, and Naomi, a Parisian Jew sent to live with relatives in Detroit, whose twin sister, Jacqueline—still in France—joins the resistance against Nazi rule.

The horrors of the concentration camps; the heroism of soldiers on the beaches of Okinawa, the skies above London, and the seas of the Mediterranean; the brilliance of code breakers; and the resilience of families waiting for the return of sons, brothers, and fathers are all conveyed through powerful, poignant prose that resonates beyond the page. Gone to Soldiers is a testament to the ordinary people, with their flaws and inner strife, who rose to defend liberty during the most extraordinary times.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Gone to Soldiers by Marge Piercy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literatura & Literatura general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

LiteraturaSubtopic

Literatura generalLOUISE 1

A Talent for Romance

Louise Kahan, aka Annette Hollander Sinclair, sorted her mail in the foyer of her apartment. An air letter from Paris. “You have something from your aunt Gloria,” she called to Kay, who was curled up in her room listening to swing music, pretending to do her homework but being stickily obsessed with boys. Louise knew the symptoms but she had never learned the cure, not in her case, certainly not in her daughter’s. Kay did not answer; presumably she could not hear over the thump of the radio.

Personal mail for Mrs. Louise Kahan in one pile. The family stuff, invitations. An occasional faux pas labeled Mr. and Mrs. Oscar Kahan. Where have you been for the past two years? Then the mail for Annette Hollander Sinclair in two stacks: one for business correspondence about rights, radio adaptations, a contract with Doubleday from her agent Charley for the collection of stories Hidden from His Sight. Speaking engagements, club visits, an interview Wednesday.

The second pile for Annette was fan mail, ninety-five percent from women. Finally a few items for plain Louise Kahan: her Daily Worker, reprints of a Masses and Mainstream article she had written on the Baltimore shipyard strike, a book on women factory workers from International Publishers for her to review, William Shirer’s Berlin Diary.

Also in that pile were the afternoon papers. Normally she would pick them up first, but she could not bring herself to do so. Europe was occupied by the Nazis from sea to sea, an immense prison. Everywhere good people and old friends were shot against walls, tortured in basements, carted off to camps about which rumors were beginning to appear to be more than rumor.

She leaned on the wall of the foyer, gathering energy to resume her life, to walk into the emotional minefield that lately seemed to constitute her relationship with Kay. The foyer was the darkest room of the suite, for the living room, her office and Kay’s bedroom enjoyed views of the Hudson River, and her own bedroom and the dining room looked down on Eighty-second Street. She had lightened the hall with a couple of cleverly placed mirrors and the big bold Miró with the spotlight on it, which she contemplated now, seeking gaiety, wit, light.

The talk she had given two hours before had bored her, if not her audience. Passing the shops hung with tinsel, she found Christmas harder to take than usual. The world was burning to ash and bone, and all her countrymen could think of was Donald Duck dressed in a Santa Claus suit. She ought to cross town to the East Side soon to get lekvar for a confection she liked to bake at Chanukah, a Hungarian-Jewish treat her mother had made, but the shop that had it was in German Yorkville. She needed a belligerent mood to brave the swastikas openly displayed, the Nazi films playing in the movie theaters, Sieg im Westen, Victory in the West, the German-American Bund passing out anti-Semitic tracts on the corners.

Next to the mail was a list of phone calls, scrawled when Kay had taken them: Ed from the Lecture Bureau called. Call him tomorrow A.M. He sounds bothered.

Some lunatic called about how she wants you to write her life story.

Daddy called.

The notes from her secretary Blanche or her housekeeper Mrs. Shaunessy were neater:

Mr. Charles Bannerman, 11:30. He wants to know if the contracts came.

Mr. Kahan, 2:30. He is in his office at Columbia.

Mr. Dennis Winterhaven, at 3, said he would call back.

Miss Dorothy Kilgallen called about interviewing you December 12.

Oscar had called twice. She tried to treat that as a casual occurrence, but nothing between them would ever be reduced to the affectless, she knew by now. At the simple decision that she must return his call, her heart perceptibly increased its flowthrough, damned traitorous pump. She cleaned up the business calls first, straightening out her schedule, glancing at the contracts and initialing where she was supposed to initial and signing where she was supposed to sign. She certainly could use the money.

She also decided she would talk to Kay before taking on her ex-husband. She knocked. At fifteen she had longed for privacy with a passion she could still remember. She granted Kay the sovereignty of her room, although it took restraint. Louise knew herself to be an anxious parent. She wanted to be closer to Kay again, as close as they had been when Kay was younger, even as she knew Kay needed to assert her independence. Somewhere was the right tone, the right voice, the right touch to ease that soreness.

“Gosh, that’s an Annette hat!” Kay said. She was sprawled on the floor, all legs and elbows and extra joints in a pleated skirt that was rapidly losing its pleats and an oversized shirt in which her barely developed body was lost, as if dissolved. She turned down the radio automatically when Louise came in.

Louise touched the hat: a cartwheel in pink and black, with a loop of veil over the eyes. “I was addressing a literary club in Oyster Bay.”

“Literary?” Kay screeched. “What do they want with you?”

“That’s what they call themselves, but they aren’t reading Thomas Mann.” Unpinning the hat, she balanced it on two fingers, twirling it. She stepped out of her high heels and sank in the rocking chair to massage her tired feet. “Did your daddy say what he wanted, Kay?”

Kay giggled. “I told him about my essay and he practically wrote it for me on the phone.”

“I’m sure that was very helpful,” Louise said, tasting the vinegar in her voice. “Did he volunteer anything else?”

Kay shrugged. Clearly she did not care to share the riches of a private conversation with her father.

Louise remembered. “Here’s a letter for you from your aunt Gloria.”

Gloria, Oscar’s sister, had been caught by the outbreak of war in Paris. Gloria was Kay’s favorite aunt, the glamorous other she longed to be: a chic black-haired beauty who worked as a stringer reporting French fashions for stateside magazines. Gloria, like Oscar, had been born in Pittsburgh, but the only steel remaining was in her will. Louise admired her sister-in-law’s willpower and her style, although Gloria had no politics besides opportunism and had married a vacuous Frenchman with more money than sense and more pride than money.

Gloria took her aunt’s duties seriously. She was childless, for her French husband, some twenty years her senior, had grown children who obviously preferred that he propagate no more. As Kay knocked through a rocky adolescence, Gloria sent her inappropriate presents (either too childish—stuffed bears—or sophisticated beaded sweaters) and anecdotal letters, which Kay cherished.

Now Louise stirred herself, sighing. She brushed a cake crumb from the skirt of her rose wool suit and looked at herself in Kay’s mirror. “You look elegant, Mommy. Why are you still dressed up? Are you going out again?”

“No, darling, not a step. I just wanted to check in with you.” She did look reasonably soignée, her complexion rosy above the rose suit, her hair well cut, close to the sides of her oval face whose best feature was still its finely chiseled bones and whose second best feature was the big grey eyes set off by auburn hair. Louise had always taken for granted being attractive to men; it was a given, not worth much consideration, but an advantage she could count on. Now she examined her looks warily, as she did her bank account each month. Expenses were high for their fatherless establishment, and the cost of living could write itself quickly on the face of a woman of thirty-eight. Little vanity was involved. She reasoned that when an advantage was lost, it was well to take that into account. But the mirror assured her she remained attractive, if that was of any use.

When she thought of marrying again, she wondered where she would put a man. After Oscar had walked out, she and Kay and Mrs. Shaunessy and her secretary Blanche had quickly filled the space. She would not give up having an office to work in, never again satisfy herself with a dainty secretary in a corner of the bedroom behind a screen. She smiled at the reflection she was no longer seeing, thinking how that setup was a symbol of the way she had had to pursue her work in a corner while living with Oscar. Everything had been subordinated to him at all times.

“Mother! You use that mirror more than I do.”

She realized Kay was sitting with Gloria’s letter unopened in her lap, waiting for her to leave so that she could engorge it in private. Feeling shut out, Louise departed at once. Supper would be better. She and Kay would talk at supper, for often that was their best time. She would turn her afternoon into a string of funny stories to make Kay laugh, then ask her about school and her friends. She was always courting her daughter lately. She had to restrain herself from buying too many presents, but maybe Saturday they could go shopping together, in the afternoon. She could remember their intimacy when she had known all Kay’s hopes and wishes and fears by heart, when she had held Kay and sung to her, “You Are My Sunshine,” and meant it. Her precious sun child whose life would be entirely different, safer and better than her own, poor and battered, growing up.

Now she could not put off calling Oscar. She thought of questioning Mrs. Shaunessy about his exact words, but her procrastination and anxiety were not yet totally out of control. Door shut, she put her bedroom telephone on her lap, then changed her mind and decided to call him on her office phone. Desk to desk. That felt safer. Louise sat in her swivel chair looking with satisfaction on the little kingdom of work she had created and then reluctantly she dialed Oscar’s number at his Columbia University office.

“Oscar? It’s Louise. You called?”

“Louie! How are you. Just a moment.” He spoke off-line. The voices continued for several moments while she sat grimacing with impatience. “Sorry to keep you waiting, but I wanted to pack off my assistant to the outer office.”

“Assistant what?”

“I’m running an interview project on German refugees. I have a student of mine interviewing the men, and a young lady of Blumenthal’s who’s going to start on the females. How are you, Louie? I spoke to Kay earlier. We had a quite intelligent conversation about the meaning of democracy.”

“Kay said you’d blocked out her essay for her over the phone.”

“Isn’t the news rotten these days? I turn on the radio expecting to hear that Moscow has fallen.”

“They’re fighting in the suburbs. I keep waiting for the legendary Russian winter to do its historic task and freeze out the Nazis—”

“I saw Oblonsky last week. He was in Leningrad, you know. He says they’re starving.”

“Not literally,” Louise said acerbically. She disliked hyperbole.

“Quite literally. People are dying of hunger and the cold. He said they’re dropping in the thousands with no one to bury them.”

Louise was silent. She and Oscar had friends among the intellectuals and writers of Leningrad, a city they preferred to Moscow. Oscar spoke some Russian, and they had visited the Soviet Union in 1938. Finally she said, “I suppose we won’t know till the war is over what’s happened to everyone.” She sighed and Oscar at his end sighed too. “Oh, Gloria wrote Kay.”

“What did she have to say?”

“You’ll have to ask your daughter.”

“I’m sure Gloria is fine. She’s well insulated from the Nazis, and I can’t imagine why they’d take an interest in her. I do wish she’d get herself back here, but I suppose she sees little reason to pick up and leave. After all, she’s a citizen of a neutral power.”

“What’s on your mind, Oscar? I had two messages from you.”

“Sunday’s our anniversary. The seventh, right?”

“It was extraordinary for you to remember it the fifteen years we were married, all my friends used to tell me, but don’t you think it’s superfluous to note it since we’re divorced?”

“I still don’t know why you wanted a divorce—”

“It’s been final for a year now. Isn’t that late to debate it? I found it absurd being married to a man I was no longer living with.”

“Don’t let’s quarrel about that now. I thought it would be nice to have supper together for old time’s sake. After all, we’ll think about each other all evening anyhow. Why not do it together?”

“Are you asking me for a date, Oscar?” She sounded ridiculous, but she was playing for time.

“That’s what I’m doing. Wouldn’t it be rather sweet? We haven’t sat down in a civilized way and shared a good meal and a bottle of wine in ages. I’d love to tell you what I’m doing. And hear all your news too, of course.”

Oscar hated to let go of women. He tried to retain all his old girlfriends in one or another capacity, friends, colleagues, dependents, at least acquaintances. He was used to demanding his widowed mother’s attention still. He could not see why he should ever let go of any woman whose attendance he had enjoyed. He also knew how to manipulate her desire for advice and commiseration on her problems with Kay. She could not imagine ceasing to be curious about Oscar; one problem she had with all other men was comparing them to him. Dennis Winterhaven said she made Oscar into a myth, but he did not know Oscar.

“Come, Louie, why not? I’ll take you anyplace you want to go. But I’ve discovered a wonderful Spanish restaurant on Fourteenth, refugees of course, fine guitarist, perfect paella.”

She was supposed to see Dennis that evening, but not till seven. They were having supper and then he was taking her to hear Hildegarde at the Savoy. “I have plans for Sunday evening. But I could have Sunday dinner with you.”

“Pick you up at one?”

“Fine.” The moment she hung up she paced her office. Why had she agreed? Because she could not resist seeing him. She would be safe, seeing Dennis just afterward. Oscar was right, of course; she would spend the evening thinking of him. She wished she had the capacity to fall in love with Dennis. The dinner was theoretically rich in possibilities. How to use her skittery feelings? Her fingers sketched circles on the pad. She could not have a divorcée as heroine. They were only the occasional villainess in the slick magazines. She herself adored the racy sound of being a divorcée. She had graduated from dull wifehood, emerging a glorious tropical butterfly, but one with a wasp sting.

Could she get away with the couple being separated? Or would it have to be a man almost married, years before? That was safer. The anniversary was of the day they had almost married, but she had decided not to. Now why? Louise glanced at the clock. She had a couple of hours before dinner. She dug for the buried fantasy that lay in the bland story. That was her power, to exploit that vein like radioactive ore in rock, the uranium Madame Curie had worked; or, more honestly, a layer of butter cream in a cake, the power of fantasizing what women really wanted to happen. Let’s see, how about a widow? Widowed young? They weren’t into war deaths yet, but how about an accident? No blame attached, proceed at your own pace now. A second chance at a man you’d turned down or dropped for reasons you now know were unworthy. Yes, she would work that secret fantasy in married women that their idiot husband should suddenly drop dead and the one who got away came back on the scene. This was a sure seller.

What she needed was a good hook and a good title. A bouquet of yellow roses coming suddenly to the door. A mistake, surely. The memory years before. Call her Betsy. That’s a nice safe respectable-sounding name. It was a New England story, she decided, one of the ones she would set in her invented Cape Ann town of Glastonbury. A fisherman who went down in a storm? Or a commuting husband in a train accident? That would provide better class identification for her readers.

Funny how the phone call with Oscar set her off. She had ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Also by Marge Piercy

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Louise 1: A Talent for Romance

- Daniel 1: An Old China Hand

- Jacqueline 1: In Pursuit of the Adolescent Universal

- Abra 1: The Opening of Abra

- Naomi 1: Naomi/Nadine Is Only Half

- Bernice 1: Bernice and the Pirates

- Jeff 1: Emplumado

- Ruthie 1: Ruthie’s Saturday

- Jacqueline 2: Of Chilblains and Rotten Rutabagas

- Ruthie 2: Of Rapid Pledges

- Abra 2: Stories to Make the Ears Bleed

- Bernice 2: Bernice on Patrol

- Duvey 1: Many a Stormy Sea Will Blow

- Louise 2: The Dark Horse

- Naomi 2: Today You Are a Woman

- Daniel 2: The Great Purple Crossword Puzzle

- Jeff 2: The Creature from the Logey Swamp

- Jacqueline 3: A Star Shaped Like Pain

- Abra 3: Such a Roomy Closet

- Naomi 3: The Jaws Close

- Louise 3: Afternoon Sun

- Jeff 3: High Tea and Low Tricks

- Duvey 2: The Maltese Crossing

- Ruthie 3: Of Good Girls and Bad Girls

- Bernice 3: Bird on a Wire

- Murray 1: One More River to Cross

- Daniel 3: Daniel’s War

- Jacqueline 4: Roads of Paper

- Jeff 4: A Few Early Deaths

- Abra 4: Hands-on Experience

- Naomi 4: Home Is the Sailor

- Louise 4: Something Old and Something New

- Jacqueline 5: Of Common Wives and Thoroughbred Horses

- Daniel 4: Their Mail and Ours

- Duvey 3: The Black Pit

- Ruthie 4: Everybody Needs Somebody to Hate

- Bernice 4: Up, Up and Away

- Abra 5: What Women Want

- Louise 5: Of the Essential and the Tangential

- Jeff 5: Friends Best Know How to Wound

- Naomi 5: One Hot Week

- Jacqueline 6: Catch a Falling Star

- Ruthie 5: Candles Burn Out

- Bernice 5: The Crooked Desires of the Heart Fulfilled

- Louise 6: The End of a Condition Requiring Illusions

- Abra 6: Love’s Labor

- Daniel 5: Working in Darkness

- Murray 2: A Little Miscalculation of the Tides

- Jeff 6: A Leader of Men and a Would-be Leader of Women

- Naomi 6: A Few Words in the Mother Tongue

- Ruthie 6: What Is Given and What Is Taken Away

- Louise 7: Toward a True Appreciation of Chinese Food

- Jacqueline 7: The Chosen

- Bernice 6: In Pursuit

- Abra 7: The Loudest Rain

- Daniel 6: Under the Weeping Willow Tree

- Jeff 7: When the Postman Passes at Noon, Twice

- Naomi 7: The Tear in Things

- Jacqueline 8: Spring Mud, Spring Blood

- Ruthie 7: Woman Is Born into Trouble as the Water Flows Downward

- Bernice 7: Major Mischief

- Louise 8: I Could Not Love Thee, Dear, So Much

- Abra 8: The Great Crusade

- Jeff 8: The Die Is Cast

- Ruthie 8: Almost Mishpocheh

- Murray 3: Return to Civilization

- Jacqueline 9: An Honorable Death

- Louise 9: Rations in Kind

- Naomi 8: The Voice of the Turtledove

- Daniel 7: Flutterings

- Jacqueline 10: Up on Black Mountain

- Bernice 8: Of the One and the Many

- Louise 10: The Biggest Party of the Season

- Abra 9: The Grey Lady

- Ruthie 9: Some Photo Opportunities and a Goose

- Jacqueline 11: Arbeitsjuden Verbraucht

- Murray 4: The Agon

- Bernice 9: Taps

- Daniel 8: White for Carriers, Black for Battleships

- Naomi 9: Belonging

- Jacqueline 12: Whither Thou Goest

- Abra 10: When the Lights Come on Again

- Ruthie 10: A Killing Frost

- Louise 11: Open, Sesame

- Murray 5: An Extra Death

- Jacqueline 13: Tunneling

- Daniel 9: Lost and Found

- Bernice 10: Some Changes Made

- Louise 12: The Second Gift

- Ruthie 11: The Harvest

- Jacqueline 14: L’Chaim

- Abra 11: The View from Tokyo

- Naomi 10: Flee as a Bird to Your Mountain

- After words: Acknowledgments, a complaint or two and many thanks

- About the Author

- Copyright Page