- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

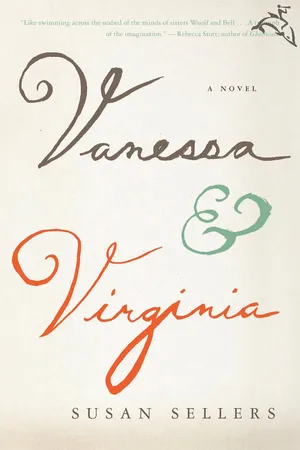

This novel of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell "captures the sisters' seesaw dynamic as they vacillate between protecting and hurting each other" (

The Christian Science Monitor).

You see, even after all these years, I wonder if you really loved me. Vanessa and Virginia are sisters, best friends, bitter rivals, and artistic collaborators. As children, they fight for the attention of their overextended mother, their brilliant but difficult father, and their adored brother, Thoby. As young women, they support each other through a series of devastating deaths, then emerge in bohemian Bloomsbury, bent on creating new lives and groundbreaking works of art. Through everything—marriage, lovers, loss, madness, children, success and failure—the sisters remain the closest of co-conspirators. But they also betray each other.

In this lyrical, impressionistic account, written as a love letter and an elegy from Vanessa to Virginia, Susan Sellers imagines her way into the heart of the lifelong relationship between writer Virginia Woolf and painter Vanessa Bell. With sensitivity and fidelity to what is known of both lives, Sellers has created a powerful portrait of sibling rivalry, and "beautifully imagines what it must have meant to be a gifted artist yoked to a sister of dangerous, provocative genius" ( Cleveland Plain Dealer).

"A delectable little book for anyone who ever admired the Bloomsbury group. . . . A genuine treat." — Publishers Weekly

You see, even after all these years, I wonder if you really loved me. Vanessa and Virginia are sisters, best friends, bitter rivals, and artistic collaborators. As children, they fight for the attention of their overextended mother, their brilliant but difficult father, and their adored brother, Thoby. As young women, they support each other through a series of devastating deaths, then emerge in bohemian Bloomsbury, bent on creating new lives and groundbreaking works of art. Through everything—marriage, lovers, loss, madness, children, success and failure—the sisters remain the closest of co-conspirators. But they also betray each other.

In this lyrical, impressionistic account, written as a love letter and an elegy from Vanessa to Virginia, Susan Sellers imagines her way into the heart of the lifelong relationship between writer Virginia Woolf and painter Vanessa Bell. With sensitivity and fidelity to what is known of both lives, Sellers has created a powerful portrait of sibling rivalry, and "beautifully imagines what it must have meant to be a gifted artist yoked to a sister of dangerous, provocative genius" ( Cleveland Plain Dealer).

"A delectable little book for anyone who ever admired the Bloomsbury group. . . . A genuine treat." — Publishers Weekly

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Vanessa & Virginia by Susan Sellers,Jenny Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

![[Image]](https://book-extracts.perlego.com/2427823/images/graphic-plgo-compressed.webp)

I AM LYING ON MY BACK ON THE GRASS. THOBY IS LYING next to me, his warm flank pressing into my side. My eyes are open and I am watching the clouds, tracing giants, castles, fabulous winged beasts as they chase each other across the sky. Something light tickles my cheek. I raise myself onto my elbow and catch hold of the grass stalk in Thoby’s hand. He jerks away from me, and soon we are pummeling and giggling until I scarcely know which of the tumbling legs and arms are Thoby’s and which are mine. When we stop at last, Thoby’s face is on my chest. I feel the weight of his head against my ribs. His hair is golden in the sunlight and as I look up I see the blazing whiteness of an angel. I loop my arm round Thoby’s neck. For the first time in my life I know what bliss means.

A shadow falls. My angel disappears. I recognize your snake-green eyes. You want to lie between us and when I push you away you jump up and whisper in Thoby’s ear. He lifts his head and looks at you. I see from his expression that your words have captured him. I know that you will lure him away with one of your daredevil plans. I roll over and press my face into the grass. The blades prickle my eyelids and I concentrate on the sharpness. When I turn round again the two of you have gone. I sit up and spot Thoby perching precariously on top of the garden wall. His hand clutches at the branches overhead as he tries to steady himself. I hear him shrieking with daring and fear. I want to shout to him to come and play in the grass with me. Then I watch you catch hold of Thoby’s leg and pull yourself up beside him. You wobble for a moment before you find your balance. I know that now you will turn and wave to me in triumph. I lie back on the grass, feigning indifference. Not for the world will I let you see my tears.

I lift my head from the page and look out the window. Sunlight shivers on the glass. For a moment I see your face as it was then, impish, grinning at me as I write. The light dissolves and you disappear. I am left staring at the empty pane. My memories are as tangled as the reels of thread and fragments of cloth in Mother’s sewing basket, which I loved to tip out and sort on the nursery floor: colored ribbons, stray buttons, a triangle of purple lace.

Mother. She enters the nursery like a queen. We, her troops, present ourselves for her inspection, fidgeting as we wait in line for our turn. Her hair is parted in the middle and tied at the back of her neck in a net. She wears a black dress, which rustles like leaves as she moves about the room, gathering up the damp clothes that have been draped over the fireguard, sweeping the scattered pieces of a puzzle back into their box. Her ringed fingers dance as she talks to the nursemaids. I learn the questions she asks them by heart. Later I will set out my dolls and quiz them in her clear round voice about castor oil and the mending. I practice standing with my head erect and my back straight until my shoulders feel as if they are pinned in a press. Finally, Mother seats herself in the chair by the fire and calls us to her.

Always, Thoby goes first. I watch him pulled into the curve of Mother’s arm, closing my eyes to imagine the silky feel of her dress, her smell of lavender and eau de nil. When I open my eyes her fingers are stroking his hair. I do not question why it is always Thoby who is first, or why, when Adrian is born, he takes his place after Thoby. I sense that this is the order of things and that here my wishes count for little. Yet when Thoby is relinquished with a kiss and Mother holds out her hand to you it is as if a promise has been broken. My stomach clenches and a hot spurt of indignation surges to my cheeks. I am the eldest. I should come before you. As Mother lifts you onto her knee your dimpled hands reach for the ribbon she wears at her throat. Checked by her reproving frown, you lean forward and kiss her. Her smile is like sunshine on a winter’s afternoon. You seem to spend an eternity in her arms. Your palms clap together in a rhyme of pat-a-cake, and when Mother praises you I wonder what would happen if a spark from the fire were to catch your petticoat. I picture your clothes igniting and your red hair blazing and Mother in her alarm hugging me to her breast.

There is a knock on the door. Ellen, slightly breathless from the stairs, holds out a card on a tray. Mother sighs and reaches for the card. When she has finished reading it she puts it back on the tray and tells Ellen that she will come straight down. She lifts you from her lap and with a final instruction to the nursemaids follows Ellen onto the landing.

I stare after her. You crawl toward me and your hand reaches for the buckle on my shoe. Quick as lightning, I kick back with my heel and trap your fingers under the sole. Your howl voices what I feel. I count to five before I lift my foot. Then I reach down and pick you up and carry you to the chair Mother sat in. I settle you on my lap and rock you backward and forward until the soft lullaby of your breathing tells me you are asleep.

It is my half sister Stella who first puts a piece of chalk in my hand. She and I share a birthday. I rummage in her pocket and pull out the package I know is there. It is wrapped in brown paper that crinkles as I turn it over in my hands. Inside are six stubby colored fingers. Stella takes a board she has concealed under her arm and draws on it. I am amazed by the wavy line that appears and reach up to try the chalk for myself. I spend the morning absorbed in my new pursuit. Though my hands are clumsy, I persevere until the board is covered. I am fascinated by the way my marks cross and join with each other, opening tiny triangles, diamonds, rectangles between the lines. When I have finished I sit back and stare at my achievement. I have transformed the dull black of the board into a rainbow of colors, a hail of shapes that jump about as I look. I am so pleased with what I have done that I hide the board away. I do not want to share my discovery with anyone.

We are in the hall dressed and ready for our walk. At our request Ellen lifts us onto the chair by the mirror so that we can see the reflections we make. Our faces are inexact replicas of each other, as if the painter were trying to capture the same person from different angles. Your face is prettier than mine, your features finer, your eyes a whirligig of quick lights. You are my natural ally in my dealings with the world. I adore the way you watch me accomplish the things you cannot yet achieve. I do not yet see the frustration, the desire to catch up and topple me that darkens your awe.

“Who do you like best, Mother or Father?” Your question comes like a bolt out of the blue. I hold the jug of warm water suspended in midair and look at you. You are kneeling on the bathmat, shiny-skinned and rosy from the steam. The ends of your hair are wet and you have a towel draped round your shoulders. I am dazzled by the audacity of your question. Slowly I let the water from the jug pour into the bath.

“Mother.” I lean back into the warmth.

You consider my answer, squeezing the damp from your hair.

“I prefer Father.”

“Father?” I sit up quickly. “How can you possibly like Father best? He’s always so difficult to please.”

“At least he’s not vague.” You spin round and look at me directly. I sense that you are enjoying this discussion.

“But Mother is . . .” I search for my word. I think of the arch of her neck as she walks into a room, the way the atmosphere changes as she seats herself at table.

“Is what?” Your eyes are daring me now.

“Beautiful.” I say the word quietly.

“What does that count for?” You do nothing to hide your contempt. “Mother doesn’t know as much as Father, she doesn’t read as much. At least when Father settles on something you know he isn’t going to be called away.”

I want to rally, hit back, protest how self-centered Father is. I want to declare Mother’s goodness, proclaim her unstinting sense of duty, her ability to restore order when all is in disarray. Instead I stare in silence at the water. From the corner of my eye I can see that you are smiling.

“Well at least we needn’t fight about who we like.” Sure of your victory, your tone now is conciliatory. I get out of the bath and wrap myself in a towel. As so often happens, our argument has made me miserable. I press my forehead against the glass of the window and watch the branches of the trees make crisscross patterns against the sky. I do not like this sifting through our feelings, weighing Mother’s merits and Father’s faults as if the answer to our lives were a simple question of arithmetic. Not for the first time, I find myself fearing where your cleverness will lead.

I want to convey the aura of those days. Father’s controlling presence, the sound of his pacing in the study above us, his clamorous, insistent groans. Mother sitting writing at her desk, preoccupied, elusive. I visualize the scene as if it were a painting. The colors are dark—black, gray, russet, wine red—with flashes of crimson from the fire. At the top of the picture are flecks of silver sky. The children kneel in the foreground. Mother, Father, our half brothers George and Gerald stand in a ring behind us, their figures monumental and restraining. Though our faces are indistinct it is possible to make out our outlines. Thoby’s arm reaches across mine, in search of a toy, perhaps, a cotton reel or wooden train. Laura hides behind Thoby, Stella’s arm curled round her in a sheltering arc. Adrian, still a baby, lies asleep in his crib. You are in the center of the picture. You seem to be painted in a different palette. Your hair is threaded with the red of the fire, your dress streaked with silver from the sky. You leap out from the monotone gloom of the rest. I cannot tell if this prominence has been forced on you, or if it is something you have sought for yourself.

“Do pay attention, Vanessa!” Mother’s rebuke startles me from my reverie and I struggle to focus on what she is telling us. She is teaching us history. Her back is as straight as a rod and her hands are folded demurely in her lap. This, too, is part of our lesson. She wishes us to learn that we must be controlled and attentive at all times. My mind skates over the list of names she is reading aloud to us. There is a picture of a crown at the top of her page and without meaning to I lose myself in its delicate crenelations.

“Vanessa! This is the second time of telling! You will please stand up and recite the kings and queens of England in order and without error!” I jump out of my chair. Your eyes are fixed on me and I sense you willing me to remember. I stammer the names of William and Henry and Stephen then grind to a stop. Before Mother can scold, you come to my rescue.

“Please, I have a question.” We both look at Mother, who nods.

“Is it true Elizabeth the First was the greatest queen England has ever known? Was she truly—a superlative monarch?” Mother smiles at your eloquence and I slink back into my chair, dejected as well as relieved. You have your permission to proceed and your eyes shine in triumph. I know that nothing will stop you now.

“Do you suppose it was because she was a woman that she achieved so much? I mean, it’s true, isn’t it, that she never married? I suppose there wasn’t a king who was good enough for her. If she had married she would have been busy having children and so wouldn’t have had time for her affairs of state. The people called her ‘Gloriana’ and she had her own motto.”

“‘Semper eadem’!” Father stands in the doorway, applauding your performance. He has the book from which he is teaching us mathematics under his arm. “‘Always the same.’ It was the motto she had inscribed on her tomb. So it’s Elizabeth the First, is it? The Virgin Queen. In that case, perhaps you had better come with me and we will see what we can find for you in my library.” You slip from your chair and take the hand Father holds out to you. I see the skip in your walk as you accompany him out of the room. The door closes behind you and I turn my attention back to Mother. I try not to hear her sigh as she begins to reread the list of names.

I thumb the pages of the family photograph album and stop at a portrait of Laura, Father’s daughter by his first marriage. She is nine, ten, perhaps, and her ringleted hair cascades over her shoulders. Her face is turned away from the camera and she clasps a small doll in her arms. It is impossible to tell her expression.

You never ridiculed Laura, I remember. Once when Thoby tried to imitate her stammering and pretended to throw his food in the fire you were so angry you slapped him. He turned to you in disbelief but the indignation on your face was real.

The day Laura was sent away you stayed in our room. It was one of your “curse” days, and when I went to see if you wanted anything I found you lying with your face buried in your pillow. As I tiptoed toward your bed you turned to look at me.

“Have they sent her to a madhouse?” I did not know the answer any more than you but shook my head.

“How could they?” I saw then the anguish in your eyes. As I put my arm around you it was my fear as well as yours I was shielding.

We lie in our beds watching the darkness. Though we plead for a crack to be left in the curtains they are pulled tight against the certainty of drafts. I close my eyes to conjure the moonlight and listen for Mother’s footsteps on the stairs. There are guests tonight and we have helped her dress. I fastened her pearl necklace carefully round her neck and she promised to come and kiss us goodnight. I imagine her sitting at the table, handing round the plates of soup. If the dinner is a success she will tell us about her labors. She will describe the fidgety young man who must be coaxed into the conversation, and the woman whose talk of ailments has to be curtailed to avert alarm. She will tell us these things not for our amusement but because she wants us to benefit from the example. We must learn, she will remind us with a judicious nod of her head, that the hostess cannot leave her place at table until those around her are at their ease. Her own wishes, and those of her daughters, must be placed second to the needs of others.

The darkness is so intense it seems to be alive. I think of the silver candelabra, drawing those seated round the table into a circle of light. A floorboard creaks and I turn toward the sound.

“Mother?” I whisper.

Your hand is on my arm. I have forgotten you in my musings. I pull back the bedclothes and make room for you. We lie shoulder to shoulder, comforted by each other’s presence. You clear your throat and begin.

“Mrs. Dilke,” you say in your storytelling voice, “was most surprised one morning to discover that the family had run out of eggs.” I settle back on my pillow and let your words weave their spell. Soon I have forgotten the darkness and Mother’s broken promise. I am caught up in your world of make-believe. I fall asleep dreaming of hobgoblins and golden hens and eggs fried for breakfast with plenty of frizzle.

“Is she reading it?”

I stand by the window that allows us to see into the drawing room from the conservatory where we work. Mother is in her armchair, the latest copy of our newspaper on the table beside her. She has a letter in her hand and I can tell from the movement of her lips that she is reading parts of it aloud to Father. He is in the armchair next to her and appears engrossed in his book. You are crouching on the floor beside me, your hands pulling nervously at a cushion. Your agitation surprises me. The newspaper is something we have compiled for fun. I peer through the window.

“She’s finishing her letter, folding it back into its envelope.”

“And has she picked up the newspaper?”

I stare at Mother. She has leaned her head back against the chair rest and closed her eyes. I watch her motionless for a few moments. You pummel the cushion in desperation. I can bear your anxiety no longer.

“Yes,” I lie. “She’s opening it now.”

“Can you see what she’s reading? Is it my piece about the pond? Does it make her laugh? What’s the expression on her face?”

I turn back to the window. Mother still has her head resting against her chair. I watch her rouse herself, pick up the newspaper, glance at its headline, then let it fall unopened on her lap. I cannot tell you what I see.

“She loves it,” I say. “She turned straight to your story and now she’s laughing her head off.” I pull the curtain firmly across the window and turn away.

You smile as if what I have told you is the most important thing in the world.

It is our ritual. You sit on the bathroom stool, a towel wrapped loosely round your shoulders. I choose lily of the valley and rose water from the shelf and stand behind you. I pour a little of the rose water into my palm and leave it for a moment to warm. Your shoulders are smooth under my fingers. I work my hands down your back, watching your skin undulate to my touch. You lay your head on my chest and as I look down I see the curl of your lashes against your cheek. I knead the soft flesh of your arms as if it is dough.

“Go on,” I nudge you gently, “carry on with the story.”

The garden is divided by hedges into a sequence of flower beds and lawns. A pocket paradise, Father calls it. We are on the terrace playing cricket....

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author