- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

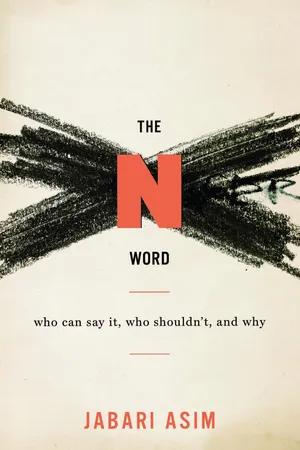

About this book

A renowned cultural critic untangles the twisted history and future of racism through its most volatile word.

The N Word reveals how the term "nigger" has both reflected and spread the scourge of bigotry in America over the four hundred years since it was first spoken on our shores. Jabari Asim pinpoints Thomas Jefferson as the source of our enduring image of the "nigger." In a seminal but now obscure essay, Jefferson marshaled a welter of pseudoscience to define the stereotype of a shiftless child-man with huge appetites and stunted self-control. Asim reveals how nineteenth-century "science" then colluded with popular culture to amplify this slander. What began as false generalizations became institutionalized in every corner of our society: the arts and sciences, sports, the law, and on the streets. Asim's conclusion is as original as his premise. He argues that even when uttered with the opposite intent by hipsters and hip-hop icons, the slur helps keep blacks at the bottom of America's socioeconomic ladder. But Asim also proves there is a place for the word in the mouths and on the pens of those who truly understand its twisted history—from Mark Twain to Dave Chappelle to Mos Def. Only when we know its legacy can we loosen this slur's grip on our national psyche.

The N Word reveals how the term "nigger" has both reflected and spread the scourge of bigotry in America over the four hundred years since it was first spoken on our shores. Jabari Asim pinpoints Thomas Jefferson as the source of our enduring image of the "nigger." In a seminal but now obscure essay, Jefferson marshaled a welter of pseudoscience to define the stereotype of a shiftless child-man with huge appetites and stunted self-control. Asim reveals how nineteenth-century "science" then colluded with popular culture to amplify this slander. What began as false generalizations became institutionalized in every corner of our society: the arts and sciences, sports, the law, and on the streets. Asim's conclusion is as original as his premise. He argues that even when uttered with the opposite intent by hipsters and hip-hop icons, the slur helps keep blacks at the bottom of America's socioeconomic ladder. But Asim also proves there is a place for the word in the mouths and on the pens of those who truly understand its twisted history—from Mark Twain to Dave Chappelle to Mos Def. Only when we know its legacy can we loosen this slur's grip on our national psyche.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The N Word by Jabari Asim in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & African American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

2

Niggerology, Part 1

I advance it therefore as a suspicion only, that the blacks, whether originally a distinct race, or made distinct by time and circumstances, are inferior to the whites in endowments both of body and mind.—Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, 1785

TO JUSTIFY THEIR AVERSION to emancipation, both to themselves and to increasingly skeptical observers from foreign lands, slaveholders adhered to what Ira Berlin has called “the logic of subordination, generally finding the sources of their own domination in some rule of nature or law of God.” Desperate to cloak their nakedly unreasonable system in the respectable garb of rationality, members of the propertied elite increasingly turned to the comforting pronouncements of scientific racism.

With his Notes on the State of Virginia—a seminal document in the American branch of this nefarious tradition—Thomas Jefferson gave himself and his peers just what they needed. First published in France, Notes reached American readers in 1785. It included a stunning section, ostensibly based on Jefferson’s “observations” of Negroes, which suggested that blacks were little more than childlike, animalistic creatures doomed to lives of permanent subservience. His ludicrous, inflammatory absurdities, relayed in the careful prose of “learned discourse,” set a poisonous precedent for the seemingly endless examples of racist pseudo-scholarship that would follow. Winthrop Jordan has called Jefferson’s remarks on the Negro “the most influential utterances on the subject” until the mid-nineteenth century. Nearly sixty years after Jefferson, Josiah Nott, another “scholar” dedicated to proving Negro inferiority, memorably dubbed his brand of science “niggerology.” In setting the stage for Nott and his cohorts, Jefferson’s Notes made the self-styled philosopher-scientist the preeminent niggerologist of his time.

While Jefferson claimed to be conflicted about slavery, he evidently harbored few doubts regarding the apparently insurmountable inferiority of Negroes. Joseph Ellis has written that the sage of Monticello “was a staunch believer in white Anglo-Saxon supremacy, as were several other leading figures in the revolutionary generation.” Yet none of his like-minded peers had dared to offer their potentially caustic summations in such carefully fashioned prose. Unlike George Washington, whom John Adams once described as having “the gift of silence,” Jefferson could rarely resist sharing his thoughts with the world.

Notes was published in the United States the year before Robert Burns offered a poetic explanation of the Negro’s plight in two lines of “The Ordination”: “How graceless Ham leugh at his dad, / Which made Canaan a nigger.” Burns echoes the long-held idea that blackness derived from a divine curse; the luckless wretches who bore its stamp were sentenced by the Creator to eternal servitude. Jefferson alludes to the concept when wondering if Negroes could be “nurtured” to a higher state of existence beyond what Nature appeared to ascribe to them. Both Burns’s poem and Jefferson’s Notes reflect the influence of Enlightenment thinking in Europe. Montesquieu’s Spirit of the Laws exerted a recognizable influence on many of the leading intellectuals of the Revolutionary generation. Published in 1748, in addition to its author’s disquisitions on types of government and principles of governing, Spirit suggests that man can improve his natural state by acquiring, among other things, knowledge and religion. In other words, basic human nature is universal but can be affected by environment and culture. Other voices of the Enlightenment argued that some “types” of mankind could not be improved. David Hume’s essay “Of National Characters,” also published in 1748, was amended five years later to include the author’s contention that “negroes and in general all other species of men . . . are naturally inferior to the whites.” Without challenging Montesquieu’s notion of the “laws of human nature,” Jefferson speculates that “time and circumstance” may be responsible for blacks’ lowly status. (The other emerging theory behind blacks’ alleged inferiority was that they were created in a different time and place from white men, a hypothesis to which we will return shortly.)

Jefferson entered the discussion just as scientists, influenced by Carolus Linnaeus’s taxonomic system of the 1730s, had begun a quest to classify just about everything—including human beings. Almost inevitably, these efforts led to hierarchical categories not entirely dissimilar to those offered by a concomitant system of thought, the Great Chain of Being. Proponents of the Chain argued that Man belonged somewhere in the middle—above Beasts and below Angels. As quasi-science met quasi-philosophy, the ranking of living things (including men) was increasingly based on supposedly measurable anatomic differences. No matter the criteria, blacks usually suffered by comparison.

Jefferson was not only the author of the Declaration of Independence but also an international symbol of American enlightenment. Thus, his anti-Negro ramblings—the most intensive ever contrived during the post-Revolutionary era—established a model of rationalized racism that would inflict incalculable damage to blacks’ quest for basic human rights.

“Animal Urges”

According to Jefferson, blacks were “more ardent after their female: but love seems with them to be more an eager desire, than a tender delicate mixture of sentiment and sensation.” He went on to argue that it was only natural for black men to prefer the superior beauty of white women, just as the “Oranootan” preferred “black women over those of his own species.” Not everyone embraced Jefferson’s bodacious claims. One of his fiercest critics was Gilbert Imlay, who in 1792 charged that Jefferson “suffered his imagination to be carried away” when predicting the amatory inclinations of apes. Such speculation, according to Imlay, was “paltry sophistry and nonsense!” Clement Clark Moore, writing in 1804, challenged Jefferson’s scientific method: “Where Mr. Jefferson learnt that the orangoutang has less affection for his own females than for black women, he does not inform us.”

Jefferson may have been familiar with William Smith’s New Voyage to Guinea, which in 1744 told of apes frequently carrying off and sexually assaulting black women in the jungles of Africa. In 1799 Britain’s Charles White, the last major niggerologist of the period, specifically referred to Jefferson’s Notes to bolster his own “research” comparing black men with apes.

In each of these perverse fantasies, black men are portrayed as wild, simian creatures, whereas black women are described as uninhibited, sexually licentious creatures, perfectly suited as targets for rampant libidinous attacks. (Such characterization also justifies the rape of black women, for how could a gentleman planter possibly cause harm to a being who is designed by nature to want sex all the time, is accustomed to the brutal techniques of uncivilized black men, and has been known to satisfy orangutans? With such a rationale, one can argue that her mere presence is tantamount to “asking for it.”)

Jefferson’s and White’s unseemly obsession with black sexuality coincided with the scientific community’s fascination with comparative anatomy. White, for example, claimed to gauge blacks’ intelligence by comparing the size of their skulls to those of whites. At the same time, white scientists’ fixation with African penises, extant since at least the fifteenth century, peaked in grisly fashion. Charles White provided an indication of just how widespread this mania was and how it was gratified. In An Account of the Regular Gradation in Man, and in Different Animals and Vegetables; and from the Former to the Latter (1799), he enthused, “That the PENIS of an African is larger than that of an European has . . . been shewn in every anatomical school in London. Preparations of them are preserved in most anatomical museums; and I have one in mine.”

One helplessly imagines a covetous spectator interrupting White’s lecture to ask “Where can I get one of those?” The proclivity of slaveowners to dismember their captives, while perhaps not as fervent as that exhibited by lynchers in the nineteenth century, nonetheless ensured that sufficient specimens remained in supply to meet the appetites of dedicated collectors such as White. The result of these “studies” was to perpetuate the stereotype of the black man as a potential rapist, whose toxic sperm would infect white purity with the “blot of infection” that blackness was thought to carry.

Back in the late eighteenth century, white men’s concerns were exacerbated by the swelling slave population. Viewed in conjunction with the related musings of Patrick Henry and Benjamin Franklin, it becomes clear that the fear of a black penis and the fear of a black planet have long been inextricably connected. Southern politicians of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (as well as Republican strategists such as Lee Atwater, who harvested abundant political capital from exactly this sort of psychosexual paranoia) owed an enormous debt of gratitude to Thomas Jefferson.

“Transient Griefs”

Remarkably, Jefferson also fancied himself privy to blacks’ innermost emotions. “Their griefs are transient,” he wrote in Notes. “Those numberless afflictions, which render it doubtful whether heaven has given life to us in mercy or in wrath, are less felt, and sooner forgotten with them.” Jefferson’s counterintuitive attempt to establish his captives’ lack of emotional depth offers proof of Roger Wilkins’s observation that “to ease their guilt, whites invented and clung to the idea that blacks had no family feeling.” Clearly, Jefferson was disturbed by the idea of slaves having emotions; that discomfort had to be part of his motive to dehumanize them so thoroughly in Notes, which appeared just as he was attempting to consolidate his various holdings and stem his financial difficulties. Part of that effort would involve getting rid of some 161 slaves over the next ten years, either by sale or by gift. Ellis suggests that Jefferson was able to perform such tasks by shielding himself from the “day-by-day realities of slave life.” At Monticello he surrounded himself with pale-skinned house servants and avoided almost all contact with the adult slaves who worked in his fields. Despite this distance, he could write confidently not only of their work habits but also of their fears, dreams, desires, and regrets. Or their alleged lack of them.

Perhaps we can also blame Jefferson’s distance from Mulberry Row (the slave quarters at Monticello) for his failure to consider that the slaves’ apparent serenity was often, in the words of Paul Laurence Dunbar, “a mask that grins and lies.” One former slave, Henry Watson, didn’t publish his memoirs until 1848, but his explanation of slave “merriment” no doubt held true during the glory years of Jefferson’s more attentive contemporaries: “the slaveholder watches every move of the slave, and if he is downcast or sad—in fact, if they are in any mood but laughing and singing, and manifesting symptoms of perfect content at heart—they are said to have the devil in them.”

“Plain Narration”

Whereas Montesquieu described man as a being “hurried away bya thousand impetuous passions,” Jefferson described blacks as “induced by the slightest amusements.” For him, blacks’ inclination toward distraction could be attributed to any number of inadequacies, from their tendency toward sensation rather than reflection, their “dull, tasteless, and anomalous” imaginations, or perhaps their “want of forethought.” All of these shortcomings contributed to Jefferson’s never having encountered a black who had “uttered a thought above the level of plain narration.”

Jefferson’s slaves included any number of highly skilled artisans, without whom the continuous construction at Monticello would not have progressed beyond his own presumably sharp, tasteful, and superior imagination; it is simply inconceivable that all of them were as inarticulate as Jefferson described. As the owner of what was probably the largest and most extensive private library in the United States, he must also have “encountered” narratives written by blacks, which began to appear around 1760. In fact, the writing by blacks during this period amounts to an eloquent counterargument to the allegations put forth by Jefferson and others, as forceful as those later advanced by Gilbert Imlay and Clement C. Moore. By the time Notes was published in the United States, James Gronniosaw, Briton Hammon, and Phillis Wheatley had already published works; Olaudah Equiano’s memoir soon followed. If Jefferson saw any merit in their efforts, he was unwilling to admit it. He pronounced Wheatley’s poems “beneath the dignity of criticism.” Ignatius Sancho’s work was far better in his view, although unequal to that of his white contemporaries—if, that is, it could even be proved that Sancho wrote it himself and “received amendment from no other hand.”

Friendly Fire

Abolitionists weren’t always much help at combating scientific racism, because all of them didn’t necessarily disagree with its chief assertion. However, some did have their own ideas about its cause. Some anti-slavers, who conceded that blacks were inferior or “depraved,” blamed their condition on the squalid environment in which the majority of them were forced to live. Therefore, their argument went, reform was not possible without emancipation. The environmental perspective had been introduced by John Woolman in Philadelphia in 1754, some twenty years before the meeting of the nation’s first anti-slavery society was held there. In Some Considerations on the Keeping of Negroes, Woolman suggested that many of the shortcomings attributed to blacks stemmed directly from their enslavement. “If Oppression be so hard to bear, that a wise Man is made mad by it . . . then a Series of those Things, altering the Behaviour and Manners of a People, is what may reasonably be expected,” he wrote. Woolman, a Quaker, implied that white men, too, would be inferior if they were enslaved.

Dr. Benjamin Rush, a prominent abolitionist in Philadelphia, echoed Woolman’s contention in 1774, asserting that “Slavery is so foreign to the human mind, that the moral faculties, as well as those of the understanding are debased, and rendered torpid by it.” Such sentiments, albeit well intentioned, did little to sway pro-slavers or anybody else. By 1800, the anti-slavery movement was all but dead.

But the image of Negroes as “brutish, ignorant, idle, crafty, treacherous, bloody, thievish, mistrustful, and superstitious” was alive and well. Jefferson’s Notes had conveniently codified “truths” held to be self-evident by the majority of white Americans at the end of the eighteenth century. In sum, black men and women were best considered as lower primates, emotionally shallow, simple-minded, sexually licentious, and prone to laziness. Contempt for blacks was so widespread, wrote David Cooper in 1772, that children were encouraged “from the first dawn of reason, to consider people with a black skin on a footing with domestic animals, form’d to serve and obey.”

A Code of Conduct

Washington and Jefferson were racists, but how racist was their language? As quintessential Southern men of their time, they behaved in public according to entrenched notions of honor, courtliness, and refinement. While violent language was considered beneath a gentleman, some forms of physical violence were not. In Affairs of Honor, Joanne B. Freeman identifies canings and nose-tweakings as acceptable components of the Revolutionary era’s “grammar of combat.” When flung at a gentleman, words such as “scoundrel,” “rascal,” and even “liar” were considered proper cause for retaliation.

In light of such customs, it is no surprise that during the constitutional convention “slavery” became in essence the “s” word, to be avoided out of respect for the delicate sensibilities of the distinguished members from the South. The delegates therefore engaged in shifty wordplay in the interests of civility, calling slaves “persons” or “persons held to Service or Labour.” In what must be considered the very apogee of irony, the Atlantic slave trade was rechristened “migrations.”

It is quite likely that Washington and Jefferson engaged in similar euphemisms at home, not out of respect to their captives, but in keeping with their concept of themselves as gentlemen of refinement. In correspondence, Washington referred to his slaves as “that species of property” (a phrase favored at the convention), “poor wretches” when he was feeling especially compassionate, and “those who are held in servitude” in missives of an official nature. At Monticello, Jefferson’s elderly slaves were quaintly called “veteran aids,” although the master was known to refer to adult black men as boys—a form of insult that gained in popularity during his time. It is reasonable to assume that the great lengths to which Jefferson shielded himself from the gritty reality of slave life included linguistic buffers as well. Crude terms such as “nigger” probably were not part of his vocabulary. Such coarseness was more appropriately left to the overseers and white men of the working class, whose tasks included the punishment and supervision of the idle wretches in the fields.

As the eighteenth century wound down, Jefferson’s peers in the creative arts also condemned the character of the Negro, replacing him in the popular imagination with a grotesque caricature so lowly and egregious that its very presence demanded its ritualistic and cathartic abuse. Taking a cue from their more sober-minded peers who wrote essays and pamphlets, creative writers added their skewed perspectives to the prevalent image of the black American, collectively fashioning a debased character of the sort Henry Louis Gates Jr. has described as “an-Other Negro, a Negro who conformed to the deepest social fears and fantasies of the larger society.”

Apparently what whites desired most in blacks was energetic servility combined with a willingness to laugh away life’s troubles. After assessing such Revolutionary literature as John Leacock’s “Fall of British Tyranny” (1776), J. Robinson’s “Yorker’s Stratagem” (1792), and John Murdock’s “Triumph of Love” (1795), the brilliant critic Sterling Brown concluded, “The earliest plays, as [well as] the earliest novels, show the Negro character chiefly as comic servant and contented slave.”

Of the Revolutionary writers, Jefferson deserves special attention for two reasons:

First, because his book endowed such fantasies with respectability and became a handy, influential primer for those who aspired to advance the cause of white supremacy. And its influence was far-reaching; Winthrop Jordan estimates that Jefferson’s remarks “were more widely read, in all probability, than any others until the mid-nineteenth century.”

Second, because Jefferson’s influence continued to rise to unparalleled heights as the sun began to set on the Revolutionary era. Ironically, blacks had played a pivotal role in his long and eventful climb. He had ...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Birth of a Notion 1619–1799

- Founding Fictions

- Niggerology, Part 1

- The Progress of Prejudice 1800–1857

- No Place to Be Somebody

- Niggerology, Part 2

- Life Among the Lowly

- Jim Crow and Company

- Dreams Deferred 1858–1896

- The World the War Made

- Nigger Happy

- Separate and Unequal 1897–1954

- Different Times

- From House Niggers to Niggerati

- Bad Niggers

- Progress and Paradox 1955–Present

- Violence and Vehemence

- To Slur with Love

- What’s in a Name?

- Nigger vs. Nigga

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author

- Connect with HMH

- Footnotes