eBook - ePub

Finding the Few

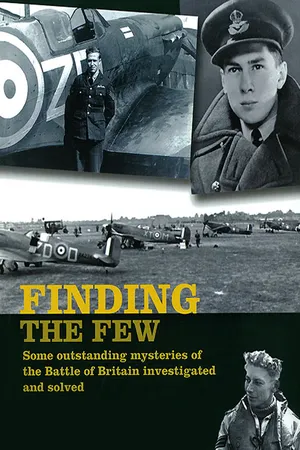

Some Outstanding Mysteries of the Battle of Britain Investigated and Solved

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Finding the Few

Some Outstanding Mysteries of the Battle of Britain Investigated and Solved

About this book

An "extraordinarily researched" account of a quest to find MIA fighter pilots decades after World War II (Barrett Tillman).

1940: The air over Britain is filled with danger. Courageous and heroic men fly and fight, often sacrificing their lives to keep the nation free. Some of them will disappear into the summer sky without leaving a trace . . .

This remarkable book records the lives of RAF pilots who were shot down and remained missing for decades—until diligent research efforts by author Andy Saunders and others brought identification to them and closure to their families. Each case represents a fascinating human story of drama, love, and tragedy; these stories are filled with startling detective work, remarkable coincidences, and shocking controversy.

Finding the Few ends with a mystery still unsolved, and features photographs throughout, standing as a fitting testament to those men lost but not forgotten.

1940: The air over Britain is filled with danger. Courageous and heroic men fly and fight, often sacrificing their lives to keep the nation free. Some of them will disappear into the summer sky without leaving a trace . . .

This remarkable book records the lives of RAF pilots who were shot down and remained missing for decades—until diligent research efforts by author Andy Saunders and others brought identification to them and closure to their families. Each case represents a fascinating human story of drama, love, and tragedy; these stories are filled with startling detective work, remarkable coincidences, and shocking controversy.

Finding the Few ends with a mystery still unsolved, and features photographs throughout, standing as a fitting testament to those men lost but not forgotten.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Finding the Few by Andy Saunders in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1 First On The List

THE FIRST name to be found on the official Battle of Britain Roll is that of Sgt Pilot Hubert Hastings Adair of 213 Squadron. In all published lists, on the Roll of Honour at Westminster Abbey and on the magnificent Battle of Britain Memorial on the Thames Embankment at Westminster Sgt Adair’s name is the first, alphabetically, to be found. It is therefore fitting that he should also be the first RAF casualty dealt with in detail within these pages. Not only is his name the first on the list of the RAF’s serving Battle of Britain aircrew but he is also one of those still classified as ‘missing’. That said, his date of death was outside the official period of the Battle of Britain (10 July-31 October 1940) but his inclusion here will surely be seen as both significant and appropriate. His ‘qualification’ for inclusion within the limited criteria set for this book is threefold. First, he was a participant in the Battle of Britain. Second, he was posted as missing in action over the UK and, thirdly, his status continues to be classified as such – notwithstanding the almost certain discovery of his bodily remains in the wreckage of a Hurricane fighter during 1979.

Sgt Hubert Hastings Adair of 213 Squadron was lost flying from RAF Tangmere on 6 November 1940. Despite the recovery of his Hurricane in the 1970's and extensive research he remains “missing” to this day.

On 6 November 1940 Hubert Adair was shot down in a short sharp battle over the Solent area. Remarkably, local schoolboy Alexander McKee snapped the vapour trails formed during that very battle from his back garden.

Teenagers Colin and Alexander McKee were keen observers of the air battles that raged around them in skies over their Hampshire home during 1940 but it was the young Alexander who enthusiastically recorded what he saw and heard during that momentous period. In his diaries, meticulously preserved post-war, Alexander had not only described in words the sights and sounds of battle but had also made sketches and watercolour paintings of some of those events. Incredibly, he even recorded some of the battles he saw via the medium of the camera lens and had made use of his limited supply of film to compile a unique perspective of the Battle of Britain through the eyes of one observer. As the aerial fighting of July and August moved on into the autumn so the young Alexander continued his avid recording, and by November he was still enthusiastically logging events. November 6th 1940 was no exception. Writing in his diary the young Alexander recorded:

“Afternoon. Sirens and then gunfire! I spotted many vapour trails over Portchester. There seemed to be several formations. First, came four planes travelling westward towards us under the trails. Two silver specks danced above, and were joined by three more. Trails formed on some of these and eight other planes in compact formation left comet-like trails. Gradually a confused mass of vapour trails like an octopus all tangled up came into being above our heads as the fighters weaved in and out. A plane stood on its ear, another looped, just like a coin spun casually upwards from the fingers. Others whirled around each other in merry circles to the chattering tune of machine guns. Then the sky rained planes. Like leaves in the autumn sky they came to earth. A Hurricane shot over Wallington very fast and at a flat angle to disappear behind the hill. Almost on its heels came another plane falling flat and fast. Neither rose again. My brother Colin then yelled ‘Look…he’s going straight down. He’s into a cloud now. He’s doing a terrible speed…’ I looked and although I failed to spot the vertical one I did see another plane descending just above the horizon.”

Although young Alexander and Colin did not know it they had witnessed the brief and bloody encounter between Me 109s of Helmut Wick’s JG2 (the Richthofen Geschwader) and the Hurricanes of 145 and 213 Squadrons up from Tangmere, the Spitfires of 602 Squadron from Westhampnett and Hurricanes of 238 Squadron from Chilbolton. Sgt Adair’s 213 Squadron had been ordered up to patrol base and then Portsmouth at 25,000 ft, or ‘Angels 25’ in RAF parlance. It was here, over Portsmouth, that the fatal encounter with the Me 109s took place – the Messerschmitts led into action by the enigmatic Luftwaffe ace Major Helmut Wick in an event that was detailed in a book called Helmut Wick – Das Leben Eines Fliegerhelden (Helmut Wick – The Life of a Flying Hero) by Josef Grabler and published in Germany during 1941. Heavily laden with more than just overtones of wartime propaganda the book must be viewed in that context, although specific episodes are carefully recorded in considerable detail. Such is the case in relation to the events of 6 November 1940 and Wick’s account of that day’s fighting provides a fascinating comparison with how things were viewed from the ground by the two McKee boys.

“Today we had a terrific time again. We meet a heap of Hurricanes which fly lower than we do. I am just getting ready to attack when I notice something above me and I immediately shout over the intercom ‘Attention! Spitfires above us!’ But they were so far away that I could begin attacking the Hurricanes. They were just turning away from their original course and that sealed their fate. Almost simultaneously the four of us fired at their formation. One went on my account. The rest of the Hurricanes moved away, but then pulled up to a higher altitude. During this manoeuvre I once again caught the one on the outer right hand side. He was done for immediately, and went straight down! Now I can’t say what it was that was the matter with me on this day, November 6. I wasn’t sure if I wasn’t well or if it was my nerves which were about to break. When my second Englishman was prone down below I just wanted to go home.

“I would have had enough fuel for a few more minutes, but the urge to go home completely overwhelmed me. Also, to justify myself – if that is at all necessary – there wasn’t much I could do with the few minutes I had left in reserve. As we begin to turn away and we are holding the course for home I spot below me three Spitfires. I am the first to see them and attack immediately. Already the first one falls! But now I say to myself ‘Go for the others!’ – if I let the other two get away they will probably shoot down my comrades tomorrow!”

Wick goes on to record his return flight across the Channel and a triumphal arrival back home when he noted to himself that the day’s ‘bag’ had taken him to 53 victories and that he had only one more claim to make before catching up with his old fighter instructor, Werner Mölders. (In fact, post-war research indicates that Wick’s tally at the day’s-end was probably 52 rather than 53.)

Clearly, and with the tactical advantage of height, Wick’s Messerschmitts had first fallen on the Hurricanes of 145 and 213 Squadrons and in a sharp and bloody encounter had bludgeoned two Hurricanes from these squadrons out of the sky. Up from Chilbolton, 238 Squadron had also joined the fray and one of their Hurricanes, too, was sent crashing to earth under the collective cannonade of JG2. The Spitfires of 602 Squadron, though, had fared rather better and came through unscathed. Indeed, and to partly redress the balance, Sgt A McDowall had sent Ofw Heinrich Klopp of 5/JG2 into the sea off Bonchurch on the Isle of Wight in his Me 109 E-4, ‘Black 1’ W.Nr 2751. Of 602 Squadron’s participation in this action, and as a counter-point to Wick’s contemporary narrative, we have the first-hand diary account of 602’s commanding officer, Squadron Leader ‘Sandy’ Johnstone. He wrote:

“Was busy dealing with a mountain of bumff in the office when a call came for the whole squadron to scramble, so I dropped everything and dashed off to lead it, as it was ages since we had had one of these! In the event, we intercepted about thirty 109s approaching the Isle of Wight but when they saw us approaching they scarpered, making no attempt to stay and fight it out. However I am pleased to say that McDowall got one as it scooted rapidly uphill. I saw it go down in flames. Some Hurricanes from Tangmere also arrived on the scene when Mac and one of the 213 boys were able to claim a second victory between them, but I did not witness that one as I was too busy trying to catch up with another 109 which was outpacing me in the climb. Lord Trenchard had been right. The Germans are behaving like a bunch of cissies!”

Again, we have here a fascinating first hand account of the action over the Solent area that day from another perspective. However, Johnstone’s remark about the Germans turning and running for home and behaving like cissies is actually rather wide of the mark and more than a little unfair on the Luftwaffe fighter pilots. We know that the Germans fought hard and well in that action and had achieved a creditable score of victories to prove so – and that is notwithstanding Wick’s surprisingly candid openness about his attack of nerves. What Johnstone probably did not realise was that the Messerschmitt 109s really had no choice other than to turn for home so quickly since they were already at the limit of their range. Fuel reserves after their brief combat were already running low for the long flight home over the sea. Indeed, so desperately short was Helmut Wick’s fuel on his return from this combat operation that he was unable to carry out the customary victory rolls over his home airfield.

Major Helmut Wick, one of the three top German aces who accounted for RAF pilots covered in this book.

Despite Wick’s assertion that he had downed at least one of Johnstone’s Spitfires (his actual claims for the combat show three Spitfires downed), this was not the case and either he incorrectly believed he had shot down some of the Spitfires or, more likely, had misidentified his Hurricane victims as Spitfires in the heat of battle. Either way, JG2 overclaimed in this action with a reported tally of eight destroyed – five Hurricanes and three Spitfires. If we count one Hurricane of 145 Squadron that made a forced-landing back at Tangmere after combat with the Messerschmitts over the Isle of Wight, then JG2’s tally can only be made to reach a maximum of four. In reality, just three fell over the actual combat zone. That said, though, there can be little doubting that all of the Hurricanes were downed by the guns of JG2 with Major Wick, Oblt Leie and Oblt Hahn all making claims around the Southampton and Isle of Wight area in this combat and with Wick claiming two Hurricanes and three Spitfires, Leie getting two Hurricanes and Hahn another Hurricane. Who shot down who it is impossible to say, especially given the element of over-claiming by the German pilots. What is certain though is that one of the victims of that combat was Sgt Hubert Adair who failed to return to his Tangmere base after the encounter. Very clearly ‘Paddy’ Adair must have been one of the fighters seen to fall by the brothers McKee and by a process of elimination, and by examining the known details of the other RAF fighter losses that day, it is possible positively to ascertain where his Hurricane fell. Again, we turn to Alexander’s diary for that clue:

“We found a woman who had bussed past a burning plane near Widley and sure enough there in a field below the road a group of tin-hatted men stood around a white gash in the soil. Overhead, where battle had raged shortly beforehand, a Hawker Hart circled around, just like a vulture floating round a corpse. I biked through a field and turned the glasses onto a small elongated tangle of silver and green metal. In most places it wasn’t more than six inches high. Smoke drifted faintly away on the wind. Twenty yards was the nearest I managed to get. One chap had seen it come down. He said it had been a Hurricane and simply dived in under full throttle at about 500mph. An ambulance stood waiting for the soldiers to pull the pilot out but the smouldering heap was too hot to touch. Small boys, though, collected bits of metal and their pockets bulged!”

What Alexander McKee had witnessed on the hill above Widley was clearly the aftermath of the vertical crash his brother Colin had seen. Who though was the pilot? From all available evidence it was clear that the unfortunate occupant had died in his Hurricane and with the established knowledge that there were only three contenders for Hurricane losses that day then there was, at least, a starting point. Of these three, however, only two were found to have known burial places. The same two could also be tied to specific crash locations. First, we have Sgt J K Haire of 145 Squadron who was shot down and killed at Heasley Farm, Arreton, on the Isle of Wight and who was taken home for burial in his native Ulster at Belfast (Dundonald) Cemetery and then we have Fg Off James Tillet of 238 Squadron who was killed when his Hurricane crashed and burnt out at Park Gate, Fareham. Tillet was taken the short distance to Anns Hill Cemetery, Gosport, for burial thus leaving only one other casualty, Sgt Hubert Adair, to consider. Of Adair, no trace had evidently been found and he was thus commemorated by name on Panel 11 of the Runnymede Memorial to the RAF’s missing. The conclusion is obvious; the body of the unfortunate Adair has never been recovered although by a process of simple deduction, his must have been the Hurricane that slammed with such awful ferocity into the chalk hill at Widley.

In 1979, and armed with Alexander McKee’s accounts, the author set out to find anyone in the Widley area who might offer more clues as to what had happened. The search did not take long. The crash was established to have happened at Pigeon House Farm and here by an incredible stroke of good fortune were found to be living Robert and Ernest Ware – two brothers who had farmed the land for the Southwick & Roche Court Estates Company since before the war. Like the McKee brothers they too had seen the battle and subsequent crash and their recall was equally vivid. The noise of the approaching aircraft was so tremendous that Robert flung himself under a farm cart for some measure of safety and, peering out, he watched as the Hurricane smashed into the field just 200 yards away shaking the ground underneath him “like an earthquake”. As it hit, a huge column of smoke, dirt and debris shot skywards and then, seemingly in slow motion, cascaded back to earth in a massive arc.

For several days the wreckage burnt underground until finally the Ware brothers were instructed to clear up the scattered debris and fill in the crater. Both were adamant in 1979 that no attempt was ever made to recover the pilot. Here then was the last resting place of Sgt Adair. Further confirmation, if any were needed, that the pilot was not recovered was provided by a former officer of the 35th Anti-Aircraft Brigade stationed at Fareham who told how a Royal Air Force officer arrived on the scene from Tangmere and searched amongst the debris where he found the aircraft serial number. This, he told the army officer, would enable the aircraft and its pilot to be identified and if true then the number the unknown officer found would have been V7602. Again if true, the RAF at Tangmere would have had clear evidence pointing to what had happened to Adair and exactly where he had crashed.

Whilst it might seem surprising that no further action was taken, it will be seen later in this book that this would not have been the first time that a crash location of a missing pilot had been found, clearly identified and then abandoned. One c...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Chapter One: First On The List

- Chapter Two: First to Be Found

- Chapter Three: The Sad Secret of Daniels Wood

- Chapter Four: Missing to Friendly Fire?

- Chapter Five: Case Not Proven

- Chapter Six: An Unforgotten Pole

- Chapter Seven: The Discovery of Hugh Beresford

- Chapter Eight: One of The Few and One of The Best

- Chapter Nine: Finding Cock-Sparrow

- Chapter Ten: Sgt Scott is No Longer Missing

- Chapter Eleven: Mistaken Identity

- Chapter Twelve: Blue One Still Missing

- Chapter Thirteen Found But Still Missing

- Chapter Fourteen: Known Unto God

- Chapter Fifteen: I Regret to Inform You ...

- Chapter Sixteen: Still Missing

- Chapter Seventeen: Those Left Behind

- Chapter Eighteen: "No Trace of Him Could Be Found..."

- Postscript: The Missing Few – An Overview

- Appendix I: The Air Forces Memorial, Runnymede

- Appendix II: The Missing Few

- Selected Bibliography

- Index