eBook - ePub

Park

The Biography of Air Chief Marshal Sir Keith Park, GCB, KBE, MC, DFC, DCL

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"A fine biography of one of the war's greatest unsung heroes," Royal Air Force Commander Keith Park (

The Daily Telegraph).

"If ever any one man won the Battle of Britain, he did. I don't believe it is realized how much that one man, with his leadership, his calm judgement and his skill, did to save not only this country, but the world." So wrote Marshal of the RAF Lord Tedder of Keith Park in 1947.

As commander of No. 11 Group, RAF Fighter Command responsible for the air defense of London and southeast England, Park took charge of the day-to-day direction of the battle. In spotlighting his thoughts and actions during the crisis, this biography reveals a man whose unfailing energy, courage, and cool resourcefulness won not only supreme praise from Winston Churchill, but the lasting respect and admiration of all who served under him.

Few officers in any of the services packed more action into their lives, and Park covers the whole of his career: youth in New Zealand, success as an ace fighter pilot in World War I, postings to South America and Egypt, the Battle of Britain, command of the RAF in Malta 1942–43, and finally Allied Air Commander-in-Chief of Southeast Asia under Mountbatten in 1945. His contribution to victory and peace was immense and this biography does much to shed light on the Big Wing controversy of 1940 and give insight into the war in Burma, 1945, and how the huge problems remaining after the war's sudden end were dealt with.

Drawn largely from unpublished sources and interviews with people who knew Park, and illustrated with maps and photographs, this is an authoritative biography of one of the world's greatest unsung heroes.

"If ever any one man won the Battle of Britain, he did. I don't believe it is realized how much that one man, with his leadership, his calm judgement and his skill, did to save not only this country, but the world." So wrote Marshal of the RAF Lord Tedder of Keith Park in 1947.

As commander of No. 11 Group, RAF Fighter Command responsible for the air defense of London and southeast England, Park took charge of the day-to-day direction of the battle. In spotlighting his thoughts and actions during the crisis, this biography reveals a man whose unfailing energy, courage, and cool resourcefulness won not only supreme praise from Winston Churchill, but the lasting respect and admiration of all who served under him.

Few officers in any of the services packed more action into their lives, and Park covers the whole of his career: youth in New Zealand, success as an ace fighter pilot in World War I, postings to South America and Egypt, the Battle of Britain, command of the RAF in Malta 1942–43, and finally Allied Air Commander-in-Chief of Southeast Asia under Mountbatten in 1945. His contribution to victory and peace was immense and this biography does much to shed light on the Big Wing controversy of 1940 and give insight into the war in Burma, 1945, and how the huge problems remaining after the war's sudden end were dealt with.

Drawn largely from unpublished sources and interviews with people who knew Park, and illustrated with maps and photographs, this is an authoritative biography of one of the world's greatest unsung heroes.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Park by Vincent Orange in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

1892 – 1936

PROLOGUE

An Undistinguished Young Man

1892-1914

Keith Rodney Park was born in Thames, a small town south-east of Auckland, on 15 June 1892. His father, James Livingstone Park, was a Scotsman, born near Aberdeen in July 1857. He was the second son of another James Park and of Mary Elphinstone, a niece of Mountstuart Elphinstone, Governor of Bombay from 1819 to 1827. In 1874, having already travelled down from Aberdeen to study at the Royal School of Mines in London’s South Kensington, James made a far longer journey to Wellington, New Zealand. He spent nearly four years as a sheep farmer before turning to geology and a career that would earn him an international reputation. In May 1880 he married Frances, daughter of a Captain William Rogers, in Wellington. They had seven daughters and three sons, of whom Keith was the ninth child and third son.

By the time of Keith’s birth, James had made a name as a mountaineer and explorer as well as a geologist. Since 1889 he had been Director of the Thames School of Mines and Keith retained several sharp memories of Thames even though he was only six when the family moved to Birkenhead, on Auckland’s North Shore. He remembered his father bringing home an amazingly heavy gold ingot from the Maunahie mine; but the ‘stampers’ or quartz crushers made the nights hideous when the Parks lived down by the mine and Keith was greatly relieved when they moved to the hill above the Maori village at Totara Point. He also remembered being told about famous men who had done poorly at school. This information encouraged him in later years because his own school record was, as he admitted, ‘undistinguished’.

In March 1901, when Keith was eight, James Park was appointed Professor of Mining at Otago University in Dunedin in the South Island. The family therefore moved again, to the other end of New Zealand, but Keith remained in Auckland, as a boarder at King’s College, until 1906. Strangely, for a man destined to earn fame as an airman, Keith loved the sea from his earliest days. He was much too keen on playing about among the ferry boats at Birkenhead to concentrate on school work. As a very small boy he would sail his father’s dinghy in the Waitemata harbour, using a stick and a holland blind for a sail. He would also swim out to ships anchored in the harbour, climb aboard and talk to sailors from many lands. That self-reliance and self-confidence remained with him all his life; so, too, did his love of the sea. His ability to swim was put to excellent use one day to save his sister Lily from drowning in a large pond. No details of this dramatic incident survive and Keith characteristically made light of it, but Lily never did.

The Park children were evidently a boisterous lot and on one occasion they prevailed upon Keith to go up a bank near their home dressed in a white sheet and wander about, moaning and groaning. Screaming with fear, the children called their father, telling him they had seen a ghost. James grabbed a gun and charged up the bank. Keith scuttled for cover when he saw his father coming, knowing him to be an accurate shot, and took some persuading home again. Thus ended ghost games in the Park household. However, on another occasion – when James was away – Keith helped to ‘lay out’ his sister Maud in a winding sheet, ringed by lighted candles and with her face chalked. The children then called their mother, lamenting poor Maud’s untimely demise. Her views on such games are not known. What is known is that she left James some time after his move to Dunedin and went to live in Australia, where she died in March 1916.

Keith, meanwhile, completed his education at Otago Boys’ High School. According to the school’s historian, there was in those years ‘an intense patriotism and enthusiasm for things military’ and Keith enrolled in the cadet force in February 1909, at the age of sixteen. Exactly a year later, Lord Kitchener of Khartoum visited the school and was practically mobbed by excited boys – and their parents. Although Keith enjoyed his first taste of military life, he did not then intend to become a professional soldier. He loved guns and horses now, as well as the sea, but he did not yet know what he wanted to do with his life.

‘I investigated the origins of Dunedin wealth,’ Keith recalled many years later, ‘and quickly learned that few men who work for anybody else accumulate much capital.’ Nevertheless, even the greatest tycoons have usually started out on someone’s payroll and so, on 1 June 1911, a fortnight before his nineteenth birthday, he joined the Union Steam Ship Company in Dunedin as a Cadet Purser. By the following April, he was a Purser (Class IV) earning £6 per month. He was employed on colliers and other coastal vessels until he graduated to the inter-colonial ships, visiting Australia and several Pacific islands. To become a purser aboard a passenger vessel naturally required a talent for discretion and at least the appearance of wide experience. Men occupying such positions were usually over twenty-five, but Park served as purser aboard three passenger vessels in 1914 when he was only twenty-two.

In December 1914 he was granted war leave and although his ambitions were to be transformed during the next four years, Park cannily withheld his resignation from the company until December 1918. Unfortunately, from a biographer’s viewpoint, he kept out of trouble throughout his three and a half years as a purser and consequently little is known about his life at that time. With his experience, he could have become an Assistant Paymaster in the New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy when war broke out, but his friends were joining the Army in the ranks and so he did too. This is Park’s own explanation, recorded many years later, but we shall see that within a year of joining up Park had chosen to cut himself off permanently from those friends and transfer to the British Army. He had already served in Dunedin as a Territorial. After the cadets at school, he had enrolled in ‘B’ Battery, New Zealand Field Artillery, in March 1911 and had remained with that battery on a part-time basis until his discharge in November 1913.

As a father of fighting-age sons, James Park had better luck than many in the First World War. All three served and all three survived. The two eldest came home, but James would not meet Keith again until 1923. In 1918 James married again. Keith also married in 1918 and so father and son performed the rare feat of taking wives in the same year – a matter which afforded all concerned wry amusement for the rest of their lives. James and Keith had much in common. James was a handsome, upright man, friendly but firm with colleagues and students. He kept himself physically fit and believed in hard work. He was resilient and abstemious. Ambitious, conscientious, unwilling to countenance foolishness, particular about his rights as well as his duties, he was more widely respected than loved. James was often referred to, by friends and family alike, as ‘Captain’; Keith was known to his family as ‘Skipper’. James retained his vigour into advanced old age, dying in Oamaru on 29 July 1946, aged eighty-nine, at a time when his now-famous son was in New Zealand for the first time in over thirty years, enjoying a triumphant tour of his native land.1

CHAPTER ONE

Artilleryman: Gallipoli and the Western Front

1915 – 1916

In January 1915 the British War Council resolved that the Admiralty ‘should prepare for a naval expedition to bombard and take the Gallipoli Peninsula, with Constantinople as its objective.’ British, French, Australian and New Zealand troops were required to support this enterprise, under the command of Sir Ian Hamilton. It was supposed that the fall of Constantinople would open a line of supply to Russia, force Turkey out of the war, secure allies in the Balkans and contribute significantly to the defeat of Germany.

Purser Park and the Maunganui had returned to New Zealand from Vancouver in 1914, ending their peacetime careers. Early in the new year they set sail once more, bound this time for Egypt, as part of the Third Reinforcements for the New Zealand contribution to the Gallipoli campaign. Both were now in military guise: Park as a Lance-Bombardier, the Maunganui as HMNZ Troopship No. 17. Park was promoted to Corporal on 1 February and transferred to the main body on arrival in Egypt. There he served with the 4th (Howitzer) Battery, commanded by Major N.S. Falla. Falla, like Park, was an employee of the Union Steam Ship Company. During 1915 he lent him books and encouraged his growing ambition to get on. It was in Egypt that Park saw his first aircraft. Although he and his friends were keenly interested in them, they learned only later that these aircraft were serving a useful purpose: locating and reporting a Turkish advance several days before an attack was launched.

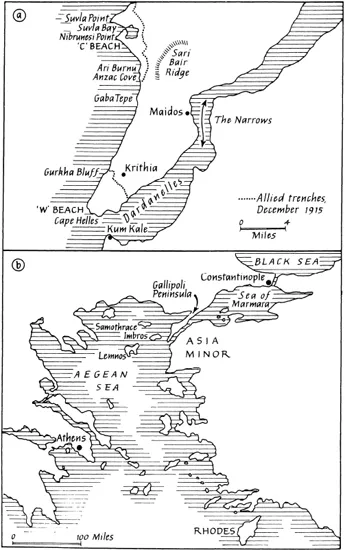

Early on 25 April 1915, British troops landed at Cape Helles on the southern tip of the Gallipoli Peninsula, French troops at Kum Kale on the Asiatic mainland and Australian and New Zealand troops on the west coast of the peninsula. The landings were fiercely opposed by Turkish forces and narrowly saved from complete disaster by the astounding bravery and resolution of the invaders. The Australians and New Zealanders scrambled ashore at what became known as Anzac Cove. Owing to the accuracy of Turkish artillery fire, the transports carrying the field guns and howitzers were forced to stand out of range. Support from the fleet’s guns was inadequate because of difficulties in communicating with the shore to direct fire to where it was most needed. Consequently, the foothold was so precarious that it would have been abandoned had it not been thought that a withdrawal would cost even heavier casualties. Thus Park spent the first Anzac Day afloat, unable to help his comrades on the shore.

1 a: Gallipoli Peninsula b: Surrounding area

Throughout that dreadful day and night, the infantry hung on in the face of ceaseless rifle and machine-gun fire. Six guns were landed at about 5.30 p.m. and their crews performed bravely until the guns were silenced. Clearly, more guns had to be got ashore somehow before dawn if the positions so courageously won were to be retained. By 6 a.m. a section of Park’s howitzer battery had been landed and set up in a gully running up to the foot of Plugge’s Plateau. It went into action as soon as possible, lifting the spirits of every surviving infantryman. ‘We had never fired the guns before,’ remembered Park fifty years later. ‘We were so short of ammunition that we had not been allowed to expend any in training.’

Once the first frenzied charges and counter-charges were spent, both sides dug in and their lines were often no more than a few yards apart. Densely packed trenches, virtually unroofed, made ideal targets for attack by howitzers, which aim to lob shells over vertical defences, unlike field guns, which try to knock them down. But Park’s battery, consisting of four 4.5-inch pieces, was the only howitzer battery at Anzac and ammunition was so scarce that it was frequently restricted to two shells per gun per day. Park’s exasperation was tempered by relief that the Turks appeared to have no howitzers at all. He was not, of course, permitted to sit idly by his silent guns. He was sent forward to pass messages down from observation officers and carried out all manner of jobs: telephonist, battery runner and general scrounger (of food and clothing).

By June, it was clear that the Allied forces were pinned down to small bridgeheads at Helles and Anzac and that a new trench warfare had begun, as fierce and sterile as that on the Western Front. Early in August an attempt was made to end the deadlock. Strong reinforcements were smuggled into the Anzac bridgehead to permit a sudden and powerful breakout, aided by a new landing a little farther north at Suvla Bay. The object was to gain the Sari Bair Ridge: that ridge, dominating the battle area, was the key to the campaign. The offensive surprised the Turks, but hesitation and incompetence among the local commanders nullified the initial advantage and led to heavy losses.

Park had been commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in July and the Suvla landings gave him his first chance to distinguish himself. His battery was on the left of the Anzac position, covering the landing of eighteen-pounders on ‘C’ Beach, south of Nibrunesi Point. The guns were put ashore without carriages, adequate supplies of ammunition or horses, and volunteers were asked to go down and impose some sort of order on the chaos. Park had never seen eighteen-pounders in action, but he agreed to go. He and his men ran along the beach to where the guns lay and man-handled them into position. They had no means of judging range, he recalled, ‘except to see that we weren’t going to blow the head off the nearest battalion commander’ and that they could clear the crest. The Turks were above them and Park’s men fired only a few rounds before they were swept by machine-gun fire. Park spent the rest of the day flat on his face in the sand.

During that month of August 1915, while taking part in a grossly mismanaged campaign in conditions of squalor such as he cannot have imagined even in nightmares, Park decided to become a regular officer in the British Army. He never subsequently commented on this momentous decision which separated him from his own countrymen and led to his shaping a career outside New Zealand. He transferred to the Royal Horse and Field Artillery as a Temporary Second Lieutenant on 1 September and was attached to the 29th Division. That division, having fought at Cape Helles since April, had been brought round to Suvla Bay to take part in the August offensive. After that offensive failed, Park returned with the 29th to Helles where he served until the evacuation.

On 24 September he was posted to No. 10 Battery, 147th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery. The gun line lay on the west of the peninsula, facing Turkish trenches in front of Krithia. The forward observation post was in the front line near Gurkha Bluff, where the trenches were only twenty-five yards from those of the enemy. The battery’s horse lines, in which Park took a particular interest, were at the bottom of Krithia Gully, well protected from enemy fire. Most of the men were reasonably fit by Gallipoli standards, although the effects of hard fighting, constant tension, bad food, worse cooking and lack of exercise were wearing them down. Nothing was done, as far as Park could remember, to provide books, papers or games to help them forget, even for a few minutes, their fear and misery.

He remembered Little Kate more happily. She was a naval twelve-pounder, well supplied with ammunition by the Navy, and despite her small size she did more damage than the rest of the battery put together. A covered emplacement was built for her on Gurkha Bluff and she did such splendid service, scattering Turkish ration parties and making their trenches dangerous, that they brought up a couple of field guns in an attempt to silence her. Although Little Kate’s position was often hit, repairs were made with sandbags each night to enable her to fire the next day.

A surviving letter written by Second Lieutenant A. Jennings, RFA, on 9 November 1915, describes his arrival at Helles in October and his early experiences in No. 10 Battery:

Park [he wrote] had landed at Anzac with the first lot and so has seen plenty of service, mostly in the ranks. He has only had his commission a few weeks. He is about my age but has seen more life than I have. When I arrived, he was ‘up forward’ in the trenches. There was no dugout for me, so I slept in Park’s. It was tiny and quite cold, but he didn’t seem to mind so I couldn’t.

Another glimpse of Park appears in his battery’s War Diary, which recorded in December that it became rather unpopular ‘because 2nd Lt. Park exercised the horses on the sky line near to Corps Headquarters resulting in the enemy shelling the sacred area.’

The evacuation from Cape Helles began for Park’s battery on 2 January 1916. Sixty rounds were fired during the afternoon and Little Kate was then removed from her position and taken to ‘W’ Beach. There she was embarked at night under the command of Park and nine men. Not long before he died, Park recalled this dangerous exercise. He felt ‘most frightened’ when ordered to take Little Kate and other guns off on flat-bottomed ‘lighters’ and sail them to Mudros harbour, on the island of Lemnos. These unseaworthy craft had little freeboard and under shelling from the Turks, ‘I was bloody scared and so were my men.’ Even when they passed beyond the range of Turkish fire, Park and his men merely exchanged one fear for another: Mudros lay some fifty miles from Cape Helles, the night was black and a heavy sea was running. As with so many other dramatic incidents in his long life, Park rarely mentioned it in later years and never in detail. By the early hours of 9 January, the battery, in the words of its War Diary, was ‘in abeyance’: scattered about ashore and afloat in the eastern Mediterranean.

Park looked back in 1946 on his Gallipoli service with a nostalgia unusual for him. He remembered the Anzac commander, Sir William Birdwood, prancing naked across the beach for his daily swim. Known as ‘Birdie’ to the troops and ‘the Soul of Anzac’ in the history books, he earned both styles, showing Park how a leader can relax without cheapening his authority. Park tried to follow many of Birdwood’s precepts: attention to detail, regular tours of inspection, indifference to personal danger and, not least, Birdwood’s recognition that the uniformed civilians of a wartime army should not be treated ‘with barrack-square discipline’. Sir Aylmer Hunter-Weston, commander of the 29th Division, taught Park equally valuable lessons. ‘Hunter-Bunter’, in Park’s opinion, was ‘a great hot air merchant’. One day he began an inspection of Park’s battery shortly after a two-man ration party had had an ‘accident’ with a jar of rum. Both men were incapable by the time the General arrived and had been hastily laid out on stretchers and covered with blankets. Hunter-Weston gazed solemnly down at the stretchers, drew himself upright and said in his best graveyard voice: ‘I salute the dead.’ As he moved away, a muffled voice rose from one of the stretchers: ‘What was the old basket saying?’ Park learned that a pompous manner earns contempt rather than respect.

He had survived a prolonged test under fire and chosen a new career. Gallipoli marked him both physically and mentally, for he was there in the ranks, seeing and sharing the exceptional squalor of that campaign, observing and suffering from the exceptional bungling of those responsible for conducting it. He had shown himself resourceful as well as brave under fire. No less important, he had also shown that he had the mental and physical toughness to function efficiently in conditions of acute, prolonged discomfort. Gallipoli has a unique place in the history of warfare: ‘for the first time,’ wrote H. A. Jones in the official history of the war in the air, ‘a campaign was conducted by combined forces on, under, and over the sea, and on and over the land.’ In the next war, Park would be among the commanders of similar combined operations in the Mediterranean and in the Indian Ocean, where many of the mistakes made at Gallipoli were avoided. But Gallipoli remains one of the greatest disasters in British history: ten thousand Anzacs left their bones there and the losses suffered by the British and French were much heavier, and all to no purpose.1

Six months after the evacuation, Park was thrust into a disaster of even greater magnitude: the Somme Offensive. Early on 16 January 1916, No. 10 Battery’s headquarters staff arrived in the 29th Division’s camp near Suez. Most of the men caught up during the next few days and strict training began because it soon became known that a transfer to the Western Front was likely. Training a...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgement

- Introduction by Christopher Shores

- Part One 1892-1936

- Part Two 1937-1940

- Part Three 1941-1946

- Part Four 1946-1975

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index