eBook - ePub

The Pyramids

The Mystery, Culture, and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments

- 512 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Pyramids

The Mystery, Culture, and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments

About this book

A "richly illustrated . . . engaging, lucid account" of Ancient Egyptian Pyramids, what we know about them now, what we don't, and what is still debated today (

Kirkus Reviews).

Hailed by Science News as "the new seminal text," The Pyramids is a comprehensive record of Egypt's most awe-inspiring monuments and what Egyptologists now know about them today—from their construction and purpose to the culture that surrounded them. Distinguished Egyptologist Miroslav Verner draws from the research of the earliest Egyptologists as well as the startling discoveries made with late twentieth century technology.

Here you will find a clear, authoritative guide to the ancient culture that created the pyramids five thousand years ago without iron or bronze, and with only the most elementary systems of calculation. As Verner explains the magnitude of this accomplishment, he also traces the stories and ideas of the intrepid scientists who uncovered the mysteries of the pyramids.

"Editor's Choice . . . this comprehensive volume details everything you ever wanted to know about pyramids." —Rosemary Herbert, Boston Herald

"Displays both a deep respect for the research of Egyptologists and a comprehensive knowledge of it . . . An important, comprehensive resource for the study of those most mysteriously, enduringly impressive structures." — Kirkus Reviews

"An accessible introduction to the culture of the ancient Egyptians." — Die Welt

Hailed by Science News as "the new seminal text," The Pyramids is a comprehensive record of Egypt's most awe-inspiring monuments and what Egyptologists now know about them today—from their construction and purpose to the culture that surrounded them. Distinguished Egyptologist Miroslav Verner draws from the research of the earliest Egyptologists as well as the startling discoveries made with late twentieth century technology.

Here you will find a clear, authoritative guide to the ancient culture that created the pyramids five thousand years ago without iron or bronze, and with only the most elementary systems of calculation. As Verner explains the magnitude of this accomplishment, he also traces the stories and ideas of the intrepid scientists who uncovered the mysteries of the pyramids.

"Editor's Choice . . . this comprehensive volume details everything you ever wanted to know about pyramids." —Rosemary Herbert, Boston Herald

"Displays both a deep respect for the research of Egyptologists and a comprehensive knowledge of it . . . An important, comprehensive resource for the study of those most mysteriously, enduringly impressive structures." — Kirkus Reviews

"An accessible introduction to the culture of the ancient Egyptians." — Die Welt

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Pyramids by Miroslav Verner, Steven Rendall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Egyptian Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

THE BIRTH OF THE PYRAMIDS

CHAPTER ONE

BEFORE THE PYRAMIDS

The Early Dynastic Period (From the Zero Dynasty to the Second Dynasty)

THE BIRTH OF EGYPT

Among the oldest and most important extant Egyptian historical documents ranks a palette commemorating King Narmer’s victory over a rebellious principality in the Nile Delta (c.3000 B.C.E.). Until recently, most Egyptologists saw this palette as providing evidence that by finally subjugating the last independent princes in the delta, Narmer created the first united Egyptian kingdom that included both Upper and Lower Egypt.

Recent archaeological research suggests, however, that Narmer was not the first king to unify Upper and Lower Egypt. In particular, the German excavations in the cemetery at Umm el-Qaab, near Abydos, have shown that the fourteen predecessors of Narmer buried there, who constituted the so-called Zero Dynasty, must have reigned over all Egypt at least part of the time, so that the true era of unification had already begun some two centuries earlier.

The arrangement of the tombs at Umm el-Qaab allows us to discern a clear continuity with the subsequent First Dynasty, and this tends to confirm the assumption that the first king of this dynasty, King Aha (fl. c.2925 B.C.E.?), was one of Narmer’s sons.* Construction of the White Walls, the fortified residence of the Egyptian kings, began in the age of unification, and was located on the boundary between the Nile Valley and the delta. The city that gradually grew up around the fortification was later known as Mennefer (Greek Memphis) and ultimately extended over several square miles. Archaeologists have still not succeeded in determining the site of the fortress, the oldest part of the city.

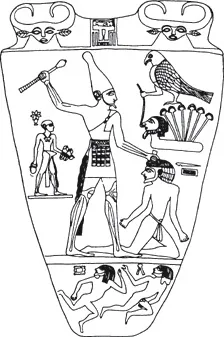

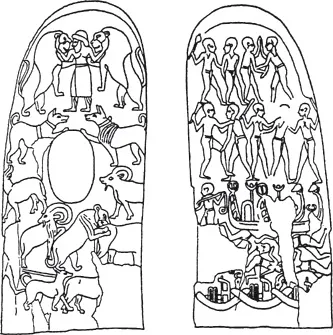

Narmer’s palette, made of dark gray slate, was found by British archaeologists at the beginning of the twentieth century, near Hierakonpolis in Upper Egypt. It is an important document for understanding the origins of Egyptian writing. Originally, palettes were rectangular or oval stone slabs on which pigments were rubbed, but the Narmer palette is already a work of art both memorial and celebratory in character. It is thought to symbolize the ruler’s success in putting down a rebellion in the delta.

On the front side of the stela is a delicate bas-relief divided into three registers. In the center of the upper register, between two cow’s heads usually interpreted as “Hathor-heads,” is a stylized image of the palace facade, with the Horus name of the last ruler of the Zero Dynasty, Narmer. This name should probably be translated as “Pungent catfish.” The middle register is dominated by the figure of Narmer, wearing the crown of Upper Egypt, about to strike with a stone club an enemy who has fallen to his knees and may be a chieftain from the east delta. The servant standing behind Narmer is carrying the pharaoh’s sandals. In front of the king the Horus-falcon holds an enemy’s head on a rope. The latter is connected with a flat oval representing a piece of land on which a papyrus plant with six blooms is growing. The papyrus symbolized Lower Egypt and also transcribes the numeral one thousand. The whole scene can thus be interpreted as follows: “The pharaoh overcame six thousand enemies from Lower Egypt and took them prisoner.” The scene is rounded out with the image of the triumphant Narmer and, according to the British Egyptologist Alan Gardiner, the author of the celebrated Egyptian Grammar, is a classical example of ancient Egyptian thinking in the earliest times. In the lower register two other vanquished enemies are represented.

On the reverse of the stela the decoration is divided into four registers. The first from the top is identical with the corresponding one on the front side. The second shows Narmer, this time with the crown of Lower Egypt on his head and in a cortege of men bearing standards with the symbols of the provinces of the victorious Upper Egyptian coalition, viewing executed enemies. The third pictorial field takes up a decorative motif that may be of Elamite origin: two fabulous creatures with intertwined necks. It is considered evidence of Near Eastern cultural influence in the Nile Valley at the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period. In the lowest register field, a bull, which like the falcon is a symbol of the ruler, smashes a fortified city and tramples down the enemies living in it.

Until well into the First Dynasty Egyptian rulers had no permanent residence. In the biennial “Horus-procession” they crossed the whole country with their retinue, in order to collect taxes, administer justice, and show themselves to the people.* The north-south dualism, which subsided only gradually, was still clearly reflected in the peculiar names of the first governmental institutions in the era of unification. Thus, e.g. the “White House,” the royal treasury, became the “Red House” after being moved to the Memphis area; the change in its name is related to the fact that the “red crown” was the symbol of Lower Egypt and the “white crown” the symbol of Upper Egypt.

As a result of increasing centralization, the administrative apparatus grew significantly larger during the First Dynasty. Members of the royal family still stood at the apex of its hierarchy. Officials were chiefly responsible for regional administration, the registration of inhabitants, controlling floods on the Nile, the construction of irrigation canals, the cultivation of fields and gardens, workshop production, and the tax system.

The consolidation of governmental administration went hand in hand with the development of writing, which ancient Egyptians considered to be divine in origin. The oldest literary traditions commemorate episodes in the battle to unify the kingdom, rites connected with the introduction of agricultural labor, and religious festivals. In addition, more practical contents are found in inscriptions on vessels, funerary stelae, annals tablets, and sealings. The oldest papyrus scroll currently known, though it bears no writing, was found in Saqqara, in the tomb of the official Hemaka. It shows that under the fifth king of the First Dynasty, Den (fl. 2850 B.C.E.), Egyptians already knew how to produce the writing materials that later became so widespread.

The ruler was at the center of the Egyptian world. He was seen as the connecting link between human beings and the gods. It was around him that the administrative apparatus of the newly developed state began to form. Royal estates were established, and undeveloped regions, particularly in the south and in the marshes of the Nile Delta, were settled and made productive by means of “internal colonization.” Despite the organization of Egypt into provinces (Greek nomoi)—ultimately twenty-two in Upper Egypt and twenty in Lower Egypt—the political unity and stability of the country remained fragile. At the end of the First Dynasty the latent oppositions between north and south resurfaced.

The first ruler of the Second Dynasty, Hetepsekhemwy (twenty-eighth century B.C.E.), whose name means “the two powers [Upper and Lower Egypt] are reconciled,” succeeded in reestablishing Egyptian unity, but not for long. Two generations later the two parts of the country were being ruled separately again. Upper Egypt was ruled from Thinis, the old center of power and administration close to Abydos, while the rest of the country was ruled from the White Walls. This internal political instability was reflected in royal titles: unlike his predecessors, the ruler Peribsen was not identified in any way with the god Horus, but rather was identified with the latter’s ideal opponent Seth, the god of evil and war. The unsettled conditions under the Second Dynasty are also manifested in the deliberate destruction of the preceding dynasty’s royal monuments in Abydos, Naqada, and Saqqara, which was motivated by the desire to obliterate not only the tombs and worship of the dead, but also and especially all memory of the dynastic opponent. The last ruler of this dynasty finally succeeded in subjugating Lower Egypt. He was originally named Khasekhem, “power shines” (or “appears in brilliance”), but changed his name to Khasekhemwy, “the two powers shine,” in order to express the unity of the gods Horus and Seth, the latter representing not only the opposing principles of good and evil, but also the formerly opposed parts of Egypt, the north and the south.

The upper border of the palace facade with Khasekhemwy’s name is unusual in depicting together the two enemy divinities Horus and Seth.

In ancient Egypt’s relationships with the ancient world surrounding it, we can already discern a few principles that were to characterize the country’s whole history. The ancient Egyptians’ religion led them to see their neighbors as enemies. Egyptians waged many wars of conquest against their neighbors, whether they lived in the east, west, or south. The most common target was Nubia, perhaps because it was more easily accessible through the corridor of the Nile Valley. In the reign of Djer, the third king of the First Dynasty, the Egyptians were already seeking to extend their influence as far as the border of present-day Sudan (see illustration p. 20).

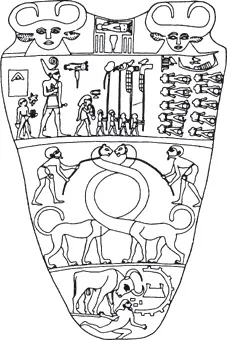

Yet Egypt’s relationships with neighboring countries were not exclusively hostile. The people of the Nile Valley also traded with their African and Near Eastern neighbors. For instance, they exported agricultural products to Palestine, evidenced by Egyptian pottery from Rafah and Arad, as well as by imprints of Egyptian seals from Tell Erama near Jerusalem. In return, they imported primarily metal products, even after the copper mines in the Sinai came under Egyptian control in the course of the First Dynasty. By way of Palestine, the ancient Egyptians also had long-standing contacts with more remote regions, as is shown by some Sumerian or Elamite motifs—a winged griffin, interlaced serpents, a man tying up animals, and zoomorphic urns and ships with towering sterns—that appeared in the Nile Valley during the First Dynasty. Some researchers found these foreign elements so striking and surprising that they arrived at the view—today outdated—that people belonging to a so-called dynastic race from Mesopotamia had ruled and “civilized” Egypt toward the end of the prehistoric era. Scholars found themselves unable to explain in any other way the rapid rise of Egypt at the beginning of the historical period. Only after new discoveries were made and evaluated did they realize that the notion of a “civilizing phase” had been based not on a sudden developmental rupture but on gaps in their own knowledge.

The stone relief from Gebel Sheikh Suleiman is considered by many Egyptologists to reflect the pharaoh Djer’s policy of conquering the region lying to the south of Egypt.

KINGSHIP AND STATE DOGMA

During the early or Thinite period (as the reign of the first two dynasties is also known), the prolonged, complicated, and often conflictual process of shaping the ancient Egyptian state that had begun toward the end of the prehistoric era, around the middle of the fourth millennium B.C.E., was finally brought to a conclusion. The fusion of the fundamentally different cultural groups of the delta and the Nile Valley played a major role in this process.

The figures incised on the ebony handle of a knife from Gebel el-Arak (Louvre E. 11517) used to be considered evidence of Near Eastern influence in Egypt at the end of the prehistoric era. On one side are hunting scenes representing a hero between two lions facing each other. The other side is decorated with scenes of battle on land and on water.

In the southern part of the country, which was inhabited primarily by nomadic shepherds, economically prosperous centers began to emerge and gain political power; among these were Hierakonpolis, Naqada, and Abydos. The rise of these new centers was aided by nearby sources of raw materials in the eastern desert and the development of foreign trade in gold and other materials.

Before the age of unification, northern Egypt, where a rather sedentary population lived and practiced agriculture, developed differently from southern Egypt. Major economic centers may have emerged there even earlier than they did in southern Egypt, especially along the banks of the navigable branches of the Nile. Closer contacts were probably established with Near Eastern urban cultures, both by land and by sea. Buto and Sais became important cities. However, archaeological sources in this part of the country remain inadequate because the complicated environmental situation makes excavation very difficult.

In contrast to the predynastic monarchs from Hierakonpolis, the princes of the great cities in the delta were probably not able to extend their rule beyond the local level. Consequently, they could not avoid military subjection to the king. Initially, the violently created bond between Upper and Lower Egypt was not very stable, being threatened by various political, economic, and religious interests.

As a result, during the Early Period the inhabitants of Lower Egypt made great efforts to win independence that culminated in the rebellions that finally led King Khasekhem to take energetic punitive action against them. This time, it seems he was successful. The subsequent long period of internal stability and relative shelter from outside influences was the crucial precondition that allowed the Old Kingdom (from the Third Dynasty to the Sixth Dynasty) to flourish.

In addition, the ideology of the ancient Egyptian state developed through the process of culturally assimilating Lower Egypt. According to the Egyptian worldview, a divine principle called maat was the foundation of everyday life. At its center stood law and order, and it was typically represented in the figure of the goddess of justice. Only if an individual obeyed the rules of maat could he achieve happiness and fulfillment, and only then could his life have any meaning in the framework of creation. This world order had to be constantly defended against the hostile powers of chaos. The ancient Egyptians believed that was why the gods set up the monarchy, which had to be supported and honored. Only the ruler, as the sole divinity living among men, could guarantee the survival of the divinely established order. In the context of the eternal myth, during his reign the ruler was obligated to overcome evil, either actually or symbolically, and evil was embodied in enemy countries and peoples. For this reason the ruler was usually represented as triumphing over Nubians, Libyans, and Asians, even when no historical facts justified such a representation.

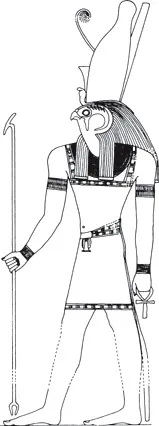

The whole system of the ancient Egyptian state was based on these ideas, which have often been described, not very precisely, as theocratic. During the Early Dynastic Period in particular, the state and the monarchy were virtually identical. The increasing importance of the state is shown by additions to the royal nomenclature. At first, the latter consisted simply of the name Horus, written in a rectangle called a serekh that was a stylized representation of t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Plate Illustrations

- Foreword

- Note on Usage

- Introduction: The Rediscovery of the Pyramids

- Part One: The Birth of the Pyramids

- Part Two: The Pyramids

- Postscript

- Epilogue: The Secret of the Pyramids

- Appendix 1: Basic Dimensions of the Pyramids

- Appendix 2: Egyptologists and Pyramid Scholars

- Appendix 3: Chronological List of Rulers and Dynasties

- Appendix 4: Glossary

- Selected Bibliography

- Index of Names

- Index of Places

- Footnotes