- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

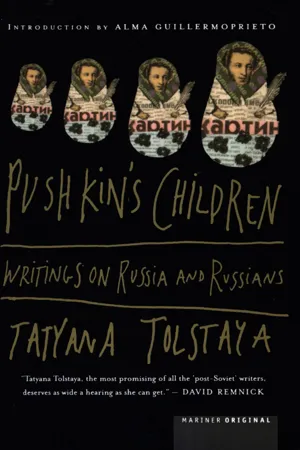

"Tolstaya's essays in this compact, historically significant volume offer a fascinating, highly intelligent analysis of Russian society and politics" (

Publishers Weekly).

These twenty essays address the politics, culture, and literature of Russia with both flair and erudition. Passionate and opinionated, often funny, and using ample material from daily life to underline their ideas and observations, Tatyana Tolstaya's piees range across a variety of subjects. They move in one unique voice from Soviet women, classical Russian cooking, and the bliss of snow to the effect of Pushkin and freedom on Russia writers; from the death of the tsar and the Great Terror to the changes brought by Gorbachev, Yeltsin, and Putin in the last decade. Throughout this engaging volume, the Russian temperament comes into high relief. Whether addressing literature or reporting on politics, Tolstaya's writing conveys a deep knowledge of her country and countrymen. Pushkin's Children is a book for anyone interested in the Russian soul.

"Tolstaya is simply the most fearless female observer of the very male-centric culture . . . of the USSR." —Ben Dickinson, Elle

These twenty essays address the politics, culture, and literature of Russia with both flair and erudition. Passionate and opinionated, often funny, and using ample material from daily life to underline their ideas and observations, Tatyana Tolstaya's piees range across a variety of subjects. They move in one unique voice from Soviet women, classical Russian cooking, and the bliss of snow to the effect of Pushkin and freedom on Russia writers; from the death of the tsar and the Great Terror to the changes brought by Gorbachev, Yeltsin, and Putin in the last decade. Throughout this engaging volume, the Russian temperament comes into high relief. Whether addressing literature or reporting on politics, Tolstaya's writing conveys a deep knowledge of her country and countrymen. Pushkin's Children is a book for anyone interested in the Russian soul.

"Tolstaya is simply the most fearless female observer of the very male-centric culture . . . of the USSR." —Ben Dickinson, Elle

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pushkin's Children by Tatyana Tolstaya in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Littérature & Collections littéraires européennes. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

LittératureMisha Gorbachev’s Small World

Review of The Man Who Changed the World: The Lives of Mikhail’S. Gorbachev, by Gail Sheehy (HarperCollins, 1990)

YOU HAVE TO BE quite fearless, an adventurer, extraordinarily self-assured, to offer American readers a book about a country that you yourself do not understand. Gail Sheehy possesses all these qualities in abundance. As she correctly indicates, “A mystery is what no one knows. The Soviet Union used to be a nest of secrets. Now it’s all mystery—even to its own leadership.” A secret that’s become a mystery is pretty hard to handle. Sheehy has written a book on the enigmatic president of a country that she has not studied, explaining the incomprehensible in terms of the unknown, and vice versa.

It is hardly surprising, therefore, that she got tangled in contradictions at the outset, was tied up in knots by the middle, was hopelessly stranded by the end, and scrambled out after 400 pages into the index (which is nearly useless, because it seethes with mistakes), without having convincingly answered any of the questions that she herself posed. Sheehy modestly refers to her book as “an X-ray of history,” but it is not nearly so probing. If a medical metaphor is wanted, I would sooner compare what she has produced to a dermatologist’s examination. Its skin deep.

The reader will learn a lot of surprising things from this book. For instance, that “diabetes is definitely a familial disease and would therefore be widespread in a closed ethnic society such as Russia, where people marry and reproduce, for the most part, with other Russians.” Sheehy seems not to know that there really is no such thing as a Russian, genetically or racially; a more diverse people would be hard to find. (Besides, there are about 150 million of them.) The reader also learns from Sheehy that the “Peredvizhniki” (more commonly known in the West as the “Wanderers”) were “a group of seventeenth-century Russian classicists,” when in fact they were critical realist painters of the late nineteenth century who broke with the Academy. (In seventeenth-century Russia there was not yet, nor could there have been, any such groups, nor any classicists.) The reader will also take away that Potemkin, one of Catherine the Greats favorites, was an architect, when his contribution to architecture, as is known, consisted of ordering the construction of decorative facades to hide the poverty and destitution of Russian villages from the empress when she rode about the country to survey her lands.

The reader is also asked to believe that Russians hate Tatars, which supposedly explains the populations friendly dislike of Raisa Gorbacheva: “Because of her wide cheek span, she is believed to have Mongol ancestors, an unappealing feature in a society that bears undisguised hatred for the Tatar-Mongols stemming from Russia’s long subjugation by both.” This “both” is especially endearing, since really only one people is under discussion, not two. If, in her headlong plunge into Russian affairs, Sheehy had relied less often on the help of the KGB, the Central Committee staff, Party bureaucrats, and would-be mistresses of Gorbachev (what a pity that no real mistresses could be found!), then she might have observed a completely different picture. Russians love to talk about their Tatar heritage. Educated Russians will inevitably quote Napoléon, who is supposed to have said, “If you scratch a Russian, you’ll find a Tatar.” Cursing the historical, almost mythological Tatars, Russians will look for the mythological Tatar in themselves.

Russians take particular pleasure in self-disparagement. They like to rub salt in old, historical wounds. (The writer Bunin called this phenomenon being “moved by your own perdition.”) Sometimes it seems that if it weren’t for the Tatar-Mongol yoke (which lasted not 500 years, as Sheehy thinks, but about 300), the Russians would have nothing to talk about. Fusing selfabasement and pride is a Russian characteristic, well described by Dostoyevsky. Raisa Maksimovna’s wide cheekbones are not her personal features, they are a trait typical of many Russian faces, which Sheehy could have noticed herself, and which Russians know perfectly well.

The number of illiterate mistakes in this book is beyond counting. I will enumerate a few of them, mixing the silly and the serious. There is no journal called “Banner and Strength” (Znamia i sila,) but there is one called “Knowledge Is Strength” (Znanie—sila). “Imenikirovna Sanitorium” is a chimera; it is the “Sanatorii imeni Kirova,” or the Kirov Sanatorium, or the Sanatorium named after Kirov. The Catcher in the Rye was not “just published” in the Soviet Union; it was translated into Russian and published in the 1960s, has been frequently reissued since, and is one of the most popular American novels in Russia (which says much about the Russian mentality). And there is this surprising sentence, which serves as an excellent test of Sheehy’s competence in matters Russian: “For a thousand years—500 under the yoke of the Mongol-Tatars, and 500 more from Ivan the Terrible to Lenin—the Russian people had no experience of liberal democracy or economic competition.”

Everything has been swept into this remarkable sentence, as if into a black hole: the pre-Mongol period; the first republic, Novgorod; the unification of the Russian principalities; the rapid growth of the country from the small kingdom of Muscovy to the giant that included the unembraceable expanses of Siberia (where there was no serfdom and economic competition abounded); the reforms of Peter the Great; the Decembrist uprising; the reforms of Alexander II; the emancipation of the serfs; Russian capitalism of the nineteenth century; and many, many more important things. Not to mention that the Tatar-Mongol yoke ended not with Ivan the Terrible but 100 or 200 years earlier, depending on how you count. All in all, Sheehy seems to have trouble with math. She assures us that she was the owner of a 260-mega byte computer, which was worth only $350. As far as I know, computers of that capacity are used only in things like Star Wars. And she gave hers to her stool pigeon-chauffeur. Generous.

Almost all the proper names in the book are garbled. A single individuals name is sometimes spelled different ways in the body of the text, and in the index it becomes entirely unrecognizable. (Brezhnev’s son-in-law suffers terribly: one time he appears correctly as the daughters husband Churbanov and another time as her lover Cherbonov.) Scolding Russian society for its patriarchy and its oppression of women, Sheehy nonetheless doesn’t bother to do Russian women the honor of spelling their names correctly, to say nothing of often changing their surnames into the masculine form, removing the feminine grammatical endings. I, too, have the misfortune to be mentioned in Sheehy’s book, and my surname is also misspelled. Worse, a conversation is ascribed to me that actually happened in a different place, at a different time, and under different circumstances than Sheehy describes. She may not care how she presents me, but I do: my story about how I interceded with the editors of a journal on behalf of certain young poets who were rejected as insufficiently traditional is transformed into a story about how I supposedly begged to be admitted to the Writers’ Union. In the Soviet Union we have always believed that Americans are legendary for their work ethic, their honesty, their sense of responsibility. Now I wonder.

Sheehy would seem to be closer to the mark when she writes that “for seven decades under their Marxist masters, [Soviets] have been isolated from the civilized world, forbidden to travel to the West, and insulated from the great currents of social, political, economic, and spiritual thought.” Well, almost. Those seventy years that everyone talks about now—everyone who wants to simplify things, to straighten out history and dump everything on the Bolsheviks as everything was previously dumped on the Tatars—were a complex and heterogeneous period. It was possible, though it was difficult, to travel to the West until about 1928, so ten years can be dropped right away. And limited travel (for a particular kind of person, at particular times, and at the price of fantastic humiliation) became possible again after 1956. So there’s another thirty years to be dropped, or at least qualified. It adds up to quite a difference. And it should not be forgotten that in the 1920s and 1930s some Western influence did exist. In those years the most influential Western politicians, writers, and philosophers visited the Soviet Union. They arrived in a country swathed in barbed wire, surveyed the Kremlin tables heavy with caviar and cognac, and heartily extolled the wonders of communism. They preferred not to hear the halfstifled moans of the victims.

This book, in short, is not to be trusted. It doesn’t even hold together as a book, though Sheehy’s pretensions to having created something monumental are clear from her title, The Man Who Changed the World. We are given the World, and the Man (Gorbachev), and the author, who has broken through the KGB’s cordons and made it to the hero’s hometown, so as to see the hero’s mother, his neighbors, his chickens, and his classmates, all with her own eyes. Breathlessly, she broke through. Breathlessly, she looked. And with what did she return? Nothing much. Was it worth all that investigative zeal just to discover that Misha had two grandfathers, and that one of them spent time in prison and the other sent people to do time in prison—a typical Soviet biography that sheds no light at all on our hero’s personality and achievements?

It is true that Sheehy displayed a certain persistence and cunning in getting to a village to which others don’t have access; but her feats and her accomplishments occupy a central place in the first half of her narrative. The reader is offered long and allegedly exciting stories about how Gail thought that Sergei might inform on her, but it turned out to be Oleg who informed. What a surprise! I can assure Sheehy that she was informed on by Oleg and Sergei, and by Arkady and Pyotr and Ivan (if she met anyone by these names), and by another couple of dozen people who smiled and helped her; and by Sergei Ivanko (an old, renowned villain whom Vladimir Voinovich made the subject of a great satire), to whom she expresses her gratitude in the introduction. Her chauffeurs informed on her, as did her maids, her translators, her neighbors, and certainly Gorbachev’s villagers; and they informed not out of any evil intent but mechanically, indifferently, as a matter of course. And those who were not actually required to inform couldn’t help it anyway: their apartments, their telephones, and their automobiles were bugged, the Moscow apartment that Sheehy inhabited was bugged, and so was the apartment of her kindly neighbors, from whom the naive and tactless Sheehy tried to borrow an egg (which, under current Russian conditions, is something like borrowing change from a beggar’s cap because you’re too lazy to go to the bank).

Please do not ask me for proof of this mass informing. I may assert that the sun rises in the morning and sets in the evening without appealing to astronomical theories. This is the way things are. And everyone knows this: every single step, every look, every breath of an American reporter who’s trying to unearth the details of the personal life and the murky past of the number-one man in the Soviet Empire is observed, recorded, and filed in a dossier. To expect that Soviet people will tell the truth to such an American reporter is ridiculous. Some will and some will not; and you’ll never know who is telling the truth, because without knowledge, experience, and informed intuition in a society like Soviet society, you can’t learn anything.

Still, Sheehy has a theory, of which she is very proud. Her theory, as is well known, is that people pass through several “lives” within their lifetimes. Or, in a word, they undergo “passages.” Sheehy has no compunction about transporting this dubious flight of American pop psychology to the Soviet Union. Thus Gorbachev is supposed to have undergone a transformation into a reformer, or a revolutionary, or something. (For some reason Sheehy fails to apply her theory to Raisa Gorbacheva.) Did Gorbachev change the world or did the world change Gorbachev? Sheehy calls this a “philosophical riddle,” and boldly takes the second hypothesis as her point of departure (thereby refuting the title of her book). Never mind that at least 2, 000 years ago the Romans noted that the times change and we change with them. But let us even grant that a “philosophy” underlies the “riddle.” The important question is whether, as a result of Sheehy’s “philosophy,” we will be enlightened about these changing times, about the processes that have taken place in Soviet society during the seventy years of its existence.

Now, our country possesses certain peculiarities that verge on the fantastic, and its inner geometry is decidedly non-Euclidean. Our roads are Mobius strips; our parallel lines cross as many times as you like; the sum of the angles of our triangles is infinite. You knock a hole through the wall of the fortress and you find yourself inside a swamp; the wall didn’t actually enclose anything. Russia is an accursed but bewitching place. It has its own logic, which the most intelligent Russian people have been unable to explain. All they could do was describe it, weep over it, and pray for it.

Sheehy appears in Russia, however, brimming with confidence, a self-proclaimed philosopher and a self-satisfied sociologist. Like Cuvier, who recovered the image of prehistoric animals from a single bone, she tries to reconstruct Russian society from random shreds of evidence. But she doesn’t know how to distinguish a bone from a boulder, and instead of full-blooded and frightening dinosaurs, she produces an impossible bestiary of talking hens and fish with eyeglasses. After visiting one market, for example, she asserts that Soviet markets are “open-air stalls . . . operated by migrant sellers from the Central Asian republics.” In fact, most Moscow markets are covered pavilions where people from all over the country sell their wares—from the Ukraine and the Caucasus, but mostly from the Moscow area. For that matter, things are often sold through surrogates, or fake “communal farmers”; the goods are frequently stolen from state stores, since they can be sold at the markets for ten times the price. And to keep everything under wraps, bribes are paid to the police, the Party secretaries at all levels, and so on, upward and upward until the money reaches—guess who?

Sheehy tells us that she decided to live in the Soviet Union just the way that Soviet people supposedly do. To this end, she pockets the salt and pepper given out with breakfast in the airplane, though I wonder how many days she planned to get by on this quantity of spices. Its a nice detail—except that Soviet people, when they steal, steal by the wagonload. If a train full of goods stalls in a provincial station, whole brigades of thieves will appear, open the sealed doors with experienced hands, and carry off every last item. Sometimes the guards and the station manager help, too. They take hundreds of thousands of rubles’ worth at a go, sometimes millions, depending on what the loot is. If you want to live like us, my dear, you better get used to our scale of operations!

Interpreting the behavior of Russian people, Sheehy ascribes motivations to them that are based on her own hastily conceived errors and homegrown theories. In this, of course, she is not alone. It has become fashionable, for example, to rebuke Russians for their indignation at Raisa Gorbacheva’s behavior: male chauvinists, that’s what they are. It doesn’t occur to Sheehy that, unlike the American president, who is elected freely by at least half the voting population, our president, or general secretary of the Communist Party, is elected by nobody. He lands on our heads all by himself, with all his stupidity, his tactlessness, his dishonesty, his shady past and unpredictable decrees. If he is unavoidable, however, like rain in autumn, or like old age, or like fate, she is not. If he has won the right to torment us (and Russians don’t doubt that the authorities exist solely in order to torment) as the result of a long, dirty struggle with other, weaker tormentors, she has not.

Raisa jabs at us—robbed, humiliated, and half-imprisoned people that we are—with her well-manicured fingers decorated with diamonds bought with our money. She screeches at us with a mouth that has tasted countless delicacies, while our children are half-starving. This woman can elicit nothing but intense scorn. She didn’t struggle for power with anyone, she received it as the result of luck, happy circumstance, and now she sets out loudly and shamelessly to make use of what she has not earned. Instructing whole peoples and republics on how they should behave, she reproaches children in the Baltics for speaking their native language instead of Russian, and she tells the Ukrainians that their capital, Kiev, is a Russian city, because “that’s what’s written in the textbooks.” If the president had, say, a brother who traveled everywhere with him, screamed, gave orders, made scenes in museums and instructed the professional staff on what they should and should not do, took over state culture as though it were his own property, got himself a gold credit card and bought diamonds with the taxpayer’s money, the reaction to that man would be precisely the same as the reaction to this woman.

As befits the product of a tabloid mentality, Sheehy’s book is lousy with “big names.” Andropov’s son and Brezhnev’s grandson touchingly discourse on the problems of the Soviet mafia as if it were something to which they had no relationship. The excited American correspondent comes to the conclusion that “ ‘organized crime’ is indeed an oxymoron in the Soviet context. Crime is no more organized than agriculture.” A big mistake: criminal activity is extremely well organized in our country. Its organized on the lowest level, from the pickpockets and the train thieves, to the highest level, where, in essence, the whole government is stolen, all rights and all freedoms are embezzled and handed out to people piecemeal, in the form of privileges.

“When did Gorbachev find out that socialism doesn’t work?” Sheehy asks anxiously. The answer is simple: he knew that nothing works while still in his mother’s womb. That’s why he embarked on a Party career. Such a career was the only way that he could find for himself a warm place within a dysfunctional system—a dangerous place, perhaps, but a privileged one. “Who suggested the idea of glasnost to him? Who first began talking about perestroika?” Another anxious question. Sheehy sets out to guess, naming first Gorbachevs boss and patron Fyodor Kulakov, then Raisa. It never occurs to her that not only the ideas of glasnost and perestroika, but the very terms themselves, have a history more than 150 years old.

In the correspondence between the Russian revolutionaries and emigrants Herzen and Ogarev, in the middle of the last century, we read about hopes for “glasnost” and “perestroika.” Russian writers, revolutionaries, and dissidents of all parties and all periods have ceaselessly talked about the necessity of reform and of freedom of expression—with variable results. Herzen and Lenin and perhaps Saltykov-Shchedrin (the nineteenth-century satirist who described the vices of Russian society and Russian psychology so exactly that his works could have been written only this morning) would have been required reading for the Gorbachevs at university.

In fact, Sheehy patronizes Gorbachev, painting the picture of a witless provincial whose “older comrades” or wife taught him everything. She patronizes him by thrilling over his ability to quote Pushkin or Lermontov, not knowing that each and every Soviet schoolchild is forced to learn poems by heart (and prose as well!) over the course of ten years of schooling. Its a bit like exalting Gorbachev for knowing his multiplication tables. And she patronizes him by calling him a “master strategist” merely because as a young flatterer he was able to carry off the most banal sort of manipulation: he ordered his assistant to lose at billiards to a high-placed official and thus gained the official’s good graces.

There is no need to marvel over the enigma of Gorbachevs soul just because he tells the Soviet people that “I am a convinced Communist” and then tells Margaret Thatcher that he is no longer a Communist. No theory is required for an explanation. It’s quite simple: he says whatever will go over better with the listener. (If he had said the opposite, now that would be truly inexplicable.) Similarly, it would be curious to consider why the general secretary of the Communist Party was ashamed of his title and decided to call himself president, after the Western fashion. After all, there are grander appellations that would have been closer to the truth. The answer, again, is simple. The term “president” soothes the Western ear and creates a subconscious image of democracy, a foggy vision of legitimacy. It brings free elections to mind. A president may receive loan credits more easily than a general secretary. Its no wonder that President Bush keeps repeating that President Gorbachev is resolved “to continue to move along the path of reform and perestroika,” despite the obvious meaninglessness of such claims.

In order to arrive at “the truth,” Sheehy has used all possible sources: honest and dishonest, clean and unclean. She has questioned intelligent people and idiots, the experienced and the inexperienced, without, it seems, being able to distinguish one from the other. There is not a trace of a critical attitude toward her material. Instead there is her trite theory of “passages.” There are moments of intelligence scattered about the book,...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Contents

- Copyright

- Introduction

- Women’s Lives

- The Great Terror and the Little Terror

- Misha Gorbachev’s Small World

- Yeltsin Routs Gorbachev

- The Future According to Alexander Solzhenitsyn

- Pushkins Children

- The Death of the Tsar

- Kitchen Conversations

- In the Ruins of Communism

- Yeltsin and Russia Lose

- The Past According to Alexander Solzhenitsyn

- On Joseph Brodsky

- Russia’s Resurrection

- Dreams of Russia, Dreams of France

- History in Photographs

- The Price of Eggs

- Snow in St. Petersburg

- Andrei Platonov’s Unusual World

- The Making of Mr. Putin

- Lies I Lived

- About the Author

- Connect with HMH

- Footnotes