eBook - ePub

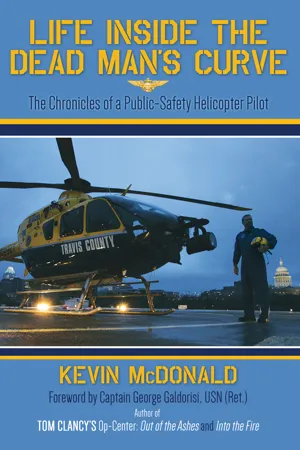

Life Inside the Dead Man's Curve

The Chronicles of a Public-Safety Helicopter Pilot

- 318 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"A warm compassionate story of helicopters in rescue missions" (Igor Sikorsky Jr., aviation historian).

Travis County STAR Flight, in Austin, Texas, is recognized as one of the premier public-safety helicopter programs in the United States. Life Inside the Dead Man's Curve is a firsthand account of the tragedy and triumph witnessed by STAR Flight crews as they respond to a myriad of emergencies, everything from traumatic injuries to rescues?and more. The author, Kevin McDonald, recounts how he turned his passion for flying into an extraordinary career filled with real-life twists and turns that will keep you on the edge of your seat from start to finish. From his early days as a naval aviator, to his twenty years as a STAR Flight pilot, Kevin takes the reader on a powerful, emotional roller coaster ride. Even if you're not an aviation enthusiast, you need to strap in for this read. This is more than a book about flying helicopters?it's a book about life, life inside the dead man's curve.

"A delightful, informative homage to a life of flight." — Kirkus Reviews

Travis County STAR Flight, in Austin, Texas, is recognized as one of the premier public-safety helicopter programs in the United States. Life Inside the Dead Man's Curve is a firsthand account of the tragedy and triumph witnessed by STAR Flight crews as they respond to a myriad of emergencies, everything from traumatic injuries to rescues?and more. The author, Kevin McDonald, recounts how he turned his passion for flying into an extraordinary career filled with real-life twists and turns that will keep you on the edge of your seat from start to finish. From his early days as a naval aviator, to his twenty years as a STAR Flight pilot, Kevin takes the reader on a powerful, emotional roller coaster ride. Even if you're not an aviation enthusiast, you need to strap in for this read. This is more than a book about flying helicopters?it's a book about life, life inside the dead man's curve.

"A delightful, informative homage to a life of flight." — Kirkus Reviews

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Life Inside the Dead Man's Curve by Kevin McDonald in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Morgan James PublishingYear

2018eBook ISBN

9781683505228Subtopic

Aviation

Chapter One

THERE I WAS, . . .

(If Only I Could Remember the Rest of the Story)

Almost every great barroom aviation story begins with these three words, “There I was.” The expanded prelude normally includes something like:

There I was, . . . upside down, in a flat spin, on fire, with three bogies on my tail.

Or, if the aviator telling the story happens to be a helicopter pilot:

There I was, . . . tail rotor gone, cyclic jammed, almost out of altitude, airspeed, and ideas.

Well, it just so happens I was a helicopter pilot, and this is my story:

There I was, . . . at Brackenridge Hospital, in downtown Austin, Texas—sitting in front of the television. It was October 12, and the Texas Rangers were playing the Detroit Tigers in game four of the 2011 American League Championship Series. Five hours into the night shift, I was comfortably ensconced in a La-Z-Boy recliner inside the STAR Flight crew quarters.

With the score tied at three runs apiece in the top of the eleventh inning, Mike Napoli came to the plate with one out and runners at first and second. He lined an RBI single to centerfield, which gave the Rangers a four to three lead and brought up Nelson Cruz, who had thus far been the hottest hitter in the series. With two runners still aboard and still only one out, the count was one ball and two strikes to Cruz when he hammered a long fly ball to left-center field. I could tell it had a chance, so I came up out of the recliner yelling for the ball to “get out!”

As the ball cleared the wall and landed in the stands, I was pumping my fist and shouting, “Yes! . . . Yes! . . . Yes!” at the top of my lungs.

Cruz’s three-run homer made it seven to three. Rangers pitcher Neftali Feliz sat the Tigers down in order in the bottom of the inning, giving Texas a three-games-to-one lead in the series. Three nights later, the Texas Rangers would win their second consecutive American League Pennant.

By that time, however, my career—and my life—had drastically altered course in a direction I could never have anticipated.

As the game ended, the on-duty flight nurse let me know she wasn’t very happy with me. She had been snoozing in a back bedroom—right up until Nelson Cruz’s three-run homer. As it turned out, it didn’t really matter that my loud celebration had interrupted her sleep because—just as she was reading me the riot act—the pager sounded, which meant we were being tasked.

The pager was an amplified, audible alarm, which let us know we had been dispatched on a call (assigned to a mission). It began with rapid-fire, high-pitched chirping sounds, followed by a series of long, deafening tones, all of which combined to make it incredibly irritating to the human ear. I had really come to hate that sound over the past twenty years. It was especially excruciating if you happened to be sleeping when it went off, so in a way, I had actually done my nurse a favor by waking her up before we were dispatched.

Once the cacophony of tones had ended, the dispatcher informed us we were being assigned to a neonatal flight with a “specialty team” from St. David’s, another nearby hospital. From our home base at Brackenridge, we would be flying to St. David’s, where we would pick up a team of nurses from their NICU (neonatal intensive care unit), then fly them sixty miles east to the hospital in La Grange (the same town where “they got a lot of nice girls” in the ZZ Top song). Once we were in La Grange, the team would spend a couple of hours stabilizing the patient, a premature baby, at which time we would fly the team and the infant back to the NICU at St. David’s in Austin.

On any other mission, we would be lifting off in the helicopter within five minutes from the time the pager went off, but specialty team flights were different. Before we could launch, there were always a few preflight administrative duties that had to be completed by the medical crew.

This gave me just enough time to scan the pantry. Hopefully, I’d find a snack, and I could make short work of it on my way up to the helipad. These missions usually took several hours to complete, and since it was already close to midnight, I knew there would be slim chow pickings at the hospital in La Grange. Unfortunately, the choices were equally lean in our pantry, so I grabbed a Diet Coke from the refrigerator and guzzled it down on my way out the door and up the stairs.

Because I was picking up an extra shift that night, I wasn’t flying with my regular crew. My flight nurse, whom I had unwittingly annoyed just moments earlier, was relatively new. Kristin McLain was, at that time, the only female crew member at STAR Flight. “STAR” stood for Shock, Trauma, Air Rescue, and the physical demands placed on STAR Flight’s medical crews were much more challenging than those required by most air ambulance programs. Not only were they tasked with providing prehospital medical care on EMS (emergency medical service) flights, the medics and nurses who flew with STAR Flight also functioned as rescue swimmers, hoist operators, and crew chiefs on a wide range of public-safety missions.

Kristin McLain had proven herself extremely competent in all of these roles. Just a month earlier, she and I had flown together on a rare nighttime fire-suppression mission. It had been an especially challenging operation, and Kristin—flying as my crew chief—had acquitted herself quite well, this despite working under some very difficult conditions. Even though she may have been slightly aggravated with me on this particular night, I still enjoyed flying with her.

My paramedic was Bill Hanson. Because we only took one STAR Flight crew member on specialty team flights, and it was Kristin’s turn in the rotation, Bill would be sitting this one out at Brackenridge. Although he wasn’t part of my regular crew, I was never disappointed when we were scheduled together. A U.S. Army veteran and a bit of a renaissance man, Bill was able to converse intelligently on a vast array of subjects. This helped pass the time on our long, twelve-hour shifts. Bill was from New Hampshire, and he liked to keep me entertained with his slightly left-of-center political views. Like most pilots, I’m somewhat conservative when it comes to ideology, and Bill was one of those rare individuals with whom you could disagree and still have a friendly, intelligent discussion about politics. That night, however, I wasn’t so much interested in convincing Bill Hanson he was wrong about supply-side economics—I just wanted him to make a doughnut run so there’d be something to eat when I returned from La Grange.

While I was sitting in the cockpit, waiting for Kristin to finish making all the preflight arrangements with the NICU team, Bill came up to the pad and assumed his post next to the external power cart. When we were at Brackenridge, we always used external power during startups to conserve the helicopter’s internal battery power.

“Is there anything you need?” Bill asked me.

Without hesitating, I answered his question. “That’s affirmative, Bill. You can go get a dozen doughnuts and have them waiting for me when we get back.”

“You know I can’t do that,” he said, laughing at my request. “If the boss calls, and I’m not here, I’ll be in big trouble.”

“It’s after midnight, Bill. Nobody’s going to call, and the doughnut shop is only ten minutes from here. You got nothin’ else to do while we’re gone. Man up!”

“Can’t do it,” he said again.

I hit the starter just as Kristin emerged from the stairwell. Then, making myself heard over the noise from the turbine spooling up, I yelled at Bill one last time.

“If you’re a team player, Bill, there’ll be doughnuts in the crew quarters when I get back!”

Bill just smiled, put his helmet on, and waited for me to give him the signal to disconnect the external power cart. As soon as the first engine was at idle, I gave him a thumbs-up. As I watched Bill flash a salute and roll the cart away, I was pretty sure there weren’t going to be any doughnuts waiting for me when I got back from La Grange.

I started the second engine, and as Kristin finished strapping into the copilot seat, I rolled both throttles to the full-open position and finished my takeoff checks. During flights with no patient on board, it was standard procedure to have a medical crew member in the cockpit, and because the NICU team would be caring for the patient during the return flight from La Grange, Kristin would be up front with me for the entire mission.

“We good to go?” I asked, scanning the cockpit gauges and checking for caution lights.

“Good to go,” she replied.

With that, I lowered my night-vision goggles and raised the collective until we were hovering just a few feet above the elevated, one-story pad. After one final cockpit check, I eased the cyclic forward and added just enough power to slide off the pad and start our climbout. Because it was such a short flight, we only had time to climb a few hundred feet before beginning our approach to the rooftop at St. David’s.

As I completed my landing checks, I could see the team of two NICU nurses getting ready to roll their isolette up the long ramp to the pad. The isolette was an incubator, mounted to a gurney to make it portable. The gurney was equipped with collapsible legs to facilitate sliding it into our helicopter, where it could then be secured to the floor. The clear plastic dome, along with the rest of the equipment mounted to the gurney, provided a controlled, sterile environment for transporting a newborn infant. The entire assembly weighed about 350 pounds, so even though we were tasked with transporting a baby, we would actually be adding the weight of two adults to the back of the helicopter.

Once we were on short final, about a hundred yards from the elevated pad, I began slowing our approach speed and arresting our descent rate. I raised the collective and eased back on the cyclic, and then, just as we were about to come to a hover over our landing spot, I lowered the collective a little and let the helicopter settle onto the pad. As she unstrapped to get out and greet the team, Kristin reminded me that we needed to shut down, so I began securing the engines.

We’d been flying the EC-145 (a medium twin-turbine helicopter) for a few years, and this “cold load” policy was a special precaution on NICU flights. The isolette had to be loaded through a pair of clamshell doors at the back of the aircraft, and the tail rotor was just a step or two from the doors. Because of the potential for someone to walk into it, we didn’t want the NICU team loading their equipment while the tail rotor was still turning.

As soon as I applied the rotor brake, and the blades came to a stop, Kristin began escorting the two nurses up the ramp, toward the pad. There was a security guard with them, and once they reached the helicopter, the guard helped Kristin and the nurses lift the isolette through the clamshells and into the cabin.

As soon as Kristin let me know the team was ready and their equipment was secured, I began lighting the engines again. Once we were at idle, I asked each nurse how much she weighed and plugged the numbers into my load schedule, a series of charts used to determine if we were below our maximum takeoff weight and within our center-of-gravity limitations. The numbers all checked good, so I ran the throttles up and went through my takeoff checks one more time.

“You ladies all set?” I asked.

“We’re good to go,” came the response from the back of the helicopter.

Kristin gave me a thumbs-up, and with that, we were off. I had no way to know in that moment that the trip from St. David’s Hospital to La Grange, though it wasn’t to be the final flight of my career, would be the last flight about which I have any personal recollection.

(to) take something for granted:

1. to fail to appreciate the value of something

2. to assume that what has been will continue to be

The half-hour trip to the hospital in La Grange was pretty much standard fare. The nurses told us the baby boy had been born prematurely, and they briefed Kristin on his condition. Trying to estimate our turnaround time at the hospital, I asked the nurses how long they would need to prep the patient for the return flight. They answered with the customary “about an hour,” but from my previous experience with these estimates, I knew this meant we would likely be on the ground for a good two and a half hours. I began pondering my prospects for a late-night pizza delivery in La Grange.

When we arrived over the hospital, I discovered that another helicopter had already parked on the helipad. It was only big enough for one bird, so this meant we would have to land in the grass instead of on the concrete pad. This was no big deal. I’d done it hundreds of times on hospital transfers. It would make it harder to roll the heavy isolette in and out of the hospital, but it was nothing three nurses and a pilot couldn’t handle.

Prior to setting up for our final approach, I circled the hospital once to check out the wind sock. Turning into the wind, I rolled final to a flat spot in the grass, about two hundred feet from the hospital. Once we’d landed, I shut the aircraft down and unstrapped so I could help Kristin and the NICU nurses unload the isolette.

The four of us alternately carried and rolled the unwieldy contraption, bouncing it through the thick St. Augustine grass, until we reached the asphalt in front of the entrance to the emergency room. Once we were on the pavement, the wheels on the gurney became functional again; so I turned the isolette over to Kristin and the NICU team, and then I went back to finish securing the doors on the helicopter. As I turned to watch Kristin and the two NICU nurses disappear into the hospital with all of their equipment, I called the only two local pizza deliveries, but neither was open at this late hour. I began settling in for what I knew was going to be a long wait.

It was a little past one o’clock in the morning, and it was mid-October. In Central Texas, the nights are usually pleasant in the fall, and this night was no exception. There was a brilliant three-quarter moon ove...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword by Captain George Galdorisi, USN (Ret.)

- Author’s Note

- How to Fly a Helicopter

- In Memoriam (for Kristin McLain)

- Prologue

- 1. There I Was, . . .

- 2. Lee Harvey Oswald, Kosmos Spoetzl, and a German Guy Named Moses . . .

- 3. A Chronic Case of Aerodynamically Induced Paranoia

- 4. Too Yong for the Job (Part One)

- 5. Too Yong for the Job (Part Two)

- 6. Anatomy of a STAR Flight Pilot

- 7. Flying Without Fear

- 8. Flying in Exile

- 9. The Leper Colony Anthology (Volume One)

- 10. The Leper Colony Anthology (Volume Two)

- 11. The Leper Colony Anthology (Volume Three)

- 12. Ejection Seats, Fires, and Flameouts

- 13. The Longest Night

- 14. Two Weeks in September

- Epilogue

- The Letter

- Acknowledgments