- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

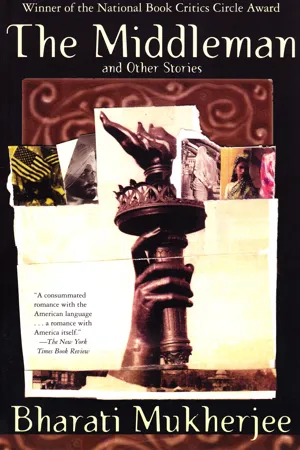

A National Book Critics Circle Award winner and

New York Times Notable Book: "intelligent, versatile . . . profound" stories of migration in America (

The Washington Post Book World).

Illuminating a new world of people in migration that has transformed the essence of America, these collected stories are a dazzling display of the vision of this critically-acclaimed contemporary writer.

An aristocratic Filipina negotiates a new life for herself with an Atlanta investment banker. A Vietnam vet returns to Florida, a place now more foreign than the Asia of his war experience. An Indian widow tries to explain her culture's traditions of grieving to her well-intentioned friends. And in the title story, an Iraqi Jew whose travels have ended in Queens suddenly finds himself an unwitting guerrilla in a South American jungle.

Passionate, comic, violent, and tender, these stories draw us into a cultural fusion in the midst of its birth pangs, expressing a "consummated romance with the American language" ( The New York Times Book Review).

Illuminating a new world of people in migration that has transformed the essence of America, these collected stories are a dazzling display of the vision of this critically-acclaimed contemporary writer.

An aristocratic Filipina negotiates a new life for herself with an Atlanta investment banker. A Vietnam vet returns to Florida, a place now more foreign than the Asia of his war experience. An Indian widow tries to explain her culture's traditions of grieving to her well-intentioned friends. And in the title story, an Iraqi Jew whose travels have ended in Queens suddenly finds himself an unwitting guerrilla in a South American jungle.

Passionate, comic, violent, and tender, these stories draw us into a cultural fusion in the midst of its birth pangs, expressing a "consummated romance with the American language" ( The New York Times Book Review).

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Middleman by Bharati Mukherjee in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

BURIED LIVES

ONE March midafternoon in Trincomalee, Sri Lanka, Mr. N. K. S. Venkatesan, a forty-nine-year-old schoolteacher who should have been inside a St. Joseph’s Collegiate classroom explicating Arnold’s “The Buried Life” found himself instead at a barricaded intersection, axe in hand and shouting rude slogans at a truckload of soldiers.

Mr. Venkatesan was not a political man. In his neighborhood he was the only householder who hadn’t contributed, not even a rupee, to the Tamil Boys’ Sporting Association, which everyone knew wasn’t a cricket club so much as a recruiting center for the Liberation Tigers. And at St. Joe’s, he hadn’t signed the staff petition abhorring the arrest at a peaceful anti-Buddhist demonstration of Dr. Pillai, the mathematics teacher. Venkatesan had rather enjoyed talking about fractals with Dr. Pillai, but he disapproved of men with family responsibilities sticking their heads between billy clubs as though they were still fighting the British for independence.

Fractals claimed to predict, mathematically, chaos and apparent randomness. Such an endeavor, if possible, struck Mr. Venkatesan as a virtually holy quest, closer to the spirit of religion than of science. What had once been Ceylon was now Sri Lanka.

Mr. Venkatesan, like Dr. Pillai, had a large family to look after: he had parents, one set of grandparents, an aunt who hadn’t been quite right in the head since four of her five boys had signed up with the Tigers, and three much younger, unmarried sisters. They lived with him in a three-room flat above a variety store. It was to protect his youngest sister (a large, docile girl who, before she got herself mixed up with the Sporting Association, used to embroider napkin-and-tablecloth sets and sell them to a middleman for export to fancy shops in Canada) that he was marching that afternoon with two hundred baby-faced protesters.

Axe under arm—he held the weapon as he might an umbrella—Mr. Venkatesan and his sister and a frail boy with a bushy moustache on whom his sister appeared to have a crush, drifted past looted stores and charred vehicles. In the center of the intersection, a middle-aged leader in camouflage fatigues and a black beret stood on the roof of a van without tires, and was about to set fire to the national flag with what looked to Mr. Venkatesan very much like a Zippo lighter.

“Sir, you have to get in the mood,” said his sister’s boyfriend. The moustache entirely covered his mouth. Mr. Venkatesan had the uncanny sensation of being addressed by a thatch of undulating bristles. “You have to let yourself go, sir.”

This wasn’t advice; this was admonition. Around Mr. Venkatesan swirled dozens of hyper kinetic boys in white shirts, holding bricks. Fat girls in summer frocks held placards aloft. His sister sucked on an ice cream bar. Every protester seemed to twinkle with fun. He didn’t know how to have fun, that was the trouble. Even as an adolescent he’d battened down all passion; while other students had slipped love notes into expectant palms, he’d studied, he’d passed exams. Dutifulness had turned him into a pariah.

“Don’t think you chaps invented civil disobedience!”

He lectured the boyfriend on how his generation—meaning that technically, he’d been alive though hardly self-conscious—had cowed the British Empire. The truth was that the one time the police had raided the Venkatesans’ flat—he’d been four, but he’d been taught anti-British phrases like “the salt march” and “satyagraha” by a cousin ten years older—he had saluted the superintendant smartly even as constables squeezed his cousin’s wrists into handcuffs. That cousin was now in San Jose, California, minting lakhs and lakhs of dollars in computer software.

The boyfriend, still smiling awkwardly, moved away from Mr. Venkatesan’s sister. His buddies, Tigers in berets, were clustered around a vendor of spicy fritters.

“Wait!” the sister pleaded, her face puffy with held-back tears.

“What do you see in that callow, good-for-nothing bloke?” Mr. Venkatesan asked.

“Please, please leave me alone,” his sister screamed. “Please let me do what I want.”

What if he were to do what he wanted! Twenty years ago when he’d had the chance, he should have applied for a Commonwealth Scholarship. He should have immured himself in a leafy dormitory in Oxford. Now it was too late. He’d have studied law. Maybe he’d have married an English girl and loitered abroad. But both parents had died, his sisters were mere toddlers, and he was obliged to take the lowest, meanest teaching job in the city.

“I want to die,” his sister sobbed beside him.

“Shut up, you foolish girl.”

The ferocity of her passion for the worthless boy, who was, just then, biting into a greasy potato fritter, shocked him. He had patronized her when she had been a plain, pliant girl squinting at embroidered birds and flowers. But now something harsh and womanly seemed to be happening inside her.

“Forget those chaps. They’re nothing but troublemakers.” To impress her, he tapped a foot to the beat of a slogan bellowing out of loudspeakers.

Though soldiers were starting to hustle demonstrators into double-parked paddy wagons, the intersection had taken on the gaudiness of a village fair. A white-haired vendor darted from police jeep to jeep hawking peanuts in paper cones. Boys who had drunk too much tea or soda relieved themselves freely into poster-clogged gutters. A dozen feet up the road a housewife with a baby on her hip lobbed stones into storefronts. A band of beggars staggered out of an electronics store with a radio and a television. No reason not to get in the mood.

“Blood for blood,” he shouted, timidly at first. “Blood begets blood.”

“Begets?” the man beside him asked. “What’s that supposed to mean?” In his plastic sandals and cheap drawstring pajamas, the man looked like a coolie or laborer.

He turned to his sister for commiseration. What could she expect him to have in common with a mob of uneducated men like that? But she’d left him behind. He saw her, crouched for flight like a giant ornament on the hood of an old-fashioned car, the March wind stiffly splaying her sari and long hair behind her.

“Get down from that car!” he cried. But the crowd, swirling, separated him from her. He felt powerless; he could no longer watch over her, keep her out of the reach of night sticks. From on top of the hood she taunted policemen, and not just policemen but everybody—shopgirls and beggars and ochre-robed monks—as though she wasn’t just a girl with a crush on a Tiger but a monster out of one’s most splenetic nightmares.

Months later, in a boardinghouse in Hamburg, Mr. Venkatesan couldn’t help thinking about the flock of young monks pressed together behind a police barricade that eventful afternoon. He owed his freedom to the monks because, in spite of their tonsure scars and their vows of stoicism, that afternoon they’d behaved like any other hot-headed Sri Lankan adolescents. If the monks hadn’t chased his sister and knocked her off the pale blue hood of the car, Mr. Venkatesan would have stayed on in Sri Lanka, in Trinco, in St. Joe’s teaching the same poems year after year, a permanent prisoner.

What the monks did was unforgivable. Robes plucked knee-high and celibate lips plumped up in vengeful chant, they pulled a girl by the hair, and they slapped and spat and kicked with vigor worthy of newly initiated Tigers.

It could have been another girl, somebody else’s younger sister. Without thinking, Mr. Venkatesan rotated a shoulder, swung an arm, readied his mind to inflict serious harm.

It should never have happened. The axe looped clumsily over the heads of demonstrators and policemen and fell, like a captured kite, into the hands of a Home Guards officer. There was blood, thick and purplish, spreading in jagged stains on the man’s white uniform. The crowd wheeled violently. The drivers of paddy wagons laid panicky fingers on their horns. Veils of tear gas blinded enemies and friends. Mr. Venkatesan, crying and choking, ducked into a store and listened to the thwack of batons. When his vision eased, he staggered, still on automatic pilot, down side streets and broke through garden hedges all the way to St. Joseph’s unguarded backdoor.

In the men’s room off the Teachers’ Common Room he held his face, hot with guilt, under a rusty, hissing faucet until Father van der Haagen, the Latin and Scriptures teacher, came out of a stall.

“You don’t look too well. Sleepless night, eh?” the Jesuit joked. “You need to get married, Venkatesan. Bad habits can’t always satisfy you.”

Mr. Venkatesan laughed dutifully. All of Father van der Haagen’s jokes had to do with masturbation. He didn’t say anything about having deserted his sister. He didn’t say anything about having maimed, maybe murdered, a Home Guards officer. “Who can afford a wife on what the school pays?” he joked back. Then he hurried off to his classroom.

Though he was over a half-hour late, his students were still seated meekly at their desks.

“Good afternoon, sir.” Boys in monogrammed shirts and rice-starched shorts shuffled to standing positions.

“Sit!” the schoolmaster commanded. Without taking his eyes off the students, he opened his desk and let his hand locate A Treasury of the Most Dulcet Verses Written in the English Language, which he had helped the headmaster to edit though only the headmaster’s name appeared on the book.

Matthew Arnold was Venkatesan’s favorite poet. Mr. Venkatesan had talked the Head into including four Arnold poems. The verses picked by the Head hadn’t been “dulcet” at all, and one hundred and three pages of the total of one hundred and seventy-four had been given over to upstart Trinco versifiers’ martial ballads.

Mr. Venkatesan would have nursed a greater bitterness against the Head if the man hadn’t vanished, mysteriously, soon after their acrimonious coediting job.

One winter Friday the headmaster had set out for his nightly after-dinner walk, and he hadn’t come back. The Common Room gossip was that he had been kidnapped by a paramilitary group. But Miss Philomena, the female teacher who was by tradition permitted the use of the Head’s private bathroom, claimed the man had drowned in the Atlantic Ocean trying to sneak into Canada in a boat that ferried, for a wicked fee, illegal aliens. Stashed in the bathroom’s air vent (through which sparrows sometimes flew in and bothered her), she’d spotted, she said, an oilcloth pouch stuffed with foreign cash and fake passports.

In the Teachers’ Common Room, where Miss Philomena was not popular, her story was discounted. But at the Pillais’ home, the men teachers had gotten together and toasted the Head with hoarded bottles of whiskey and sung many rounds of “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow,” sometimes substituting “smart” for “good.” By the time Mr. Venkatesan had been dropped home by Father van der Haagen, who owned a motorcycle, night had bleached itself into rainy dawn. It had been the only all-nighter of Mr. Venkatesan’s life and the only time he might have been accused of drunkenness.

The memory of how good the rain had felt came back to him now as he glanced through the first stanza of the assigned Arnold poem. What was the function of poetry if not to improve the petty, cautious minds of evasive children? What was the duty of the teacher if not to inspire?

He cleared his throat, and began to read aloud in a voice trained in elocution.

Light flows our war of mocking words, and yet,

Behold, with tears mine eyes are wet!

I feel a nameless sadness o’er me roll.

Yes, yes, we know that we can jest,

We know, we know that we can smile!

But there’s a something in this breast,

To which thy light words bring no rest,

And thy gay smiles no anodyne.

Give me thy hand, and hush awhile,

And turn those limpid eyes on mine,

And let me read there, love! thy inmost soul.

“Sir,” a plump boy in the front row whispered as Mr. Venkatesan finally stopped for breath.

“What is it now?” snapped Mr. Venkatesan. In his new mood Arnold had touched him with fresh intensity, and he hated the boy for deflating illusion. “If you are wanting to know a synonym for ‘anodyne,’ then look it up in the Oxford Dictionary. You are a lazy donkey wanting me to feed you with a silver spoon. All of you, you are all lazy donkeys.”

“No, sir.” The boy persisted in spoiling the mood.

It was then that Mr. Venkatesan took in the boy’s sweaty face and hair. Even the eyes were fat and sweaty.

“Behold, sir,” the boy said. He dabbed his eyelids with the limp tip of his school tie. “Mine eyes, too, are wet.”

“You are a silly donkey,” Mr. Venkatesan yelled. “You are a beast of burden. You deserve the abuse that you get. It is you emotional types who are selling this country down the river.”

The class snickered, unsure what Mr. Venkatesan wanted of them. The boy let go of his tie and wept openly. Mr. Venkatesan hated himself. Here was a kindred soul, a fellow lover of Matthew Arnold, and what had he done other than indulge in gratuitous cruelty? He blamed the times. He blamed Sri Lanka.

It was as much this classroom incident as the fear of arrest for his part in what turned out to be an out-of-control demonstration that made Mr. Venkatesan look into emigrating. At first, he explored legal channels. He wasted a month’s salary bribing arrogant junior-level clerks in four consulates—he was willing to settle almost anywhere except in the Gulf Emirates—but every country he could see himself being happy and fulfilled in turned him down.

So all through the summer he consoled himself with reading novels. Adventure stories in which fearless young Britons—sailors, soldiers, missionaries—whacked wildernesses into submission. From lending libraries in the city, he checked out books that were so old that they had to be trussed with twine. On the flyleaf of each book, in fading ink, was an inscription by a dead or retired British tea planter. Like the blond heroes of the novels, the colonials must have come to Ceylon chasing dreams of perfect futures. He, too, must sail dark, stormy oceans.

In August, at the close of a staff meeting, Miss Philomena announced coyly that she was leaving the island. A friend in Kalamazoo, Michigan, had agreed to sponsor her as a “domestic.”

“It is a ploy only, man,” Miss Philomena explained. “In the autumn, I am signing up for post-graduate studies in a prestigious educational institution.”

“You are cleaning toilets and whatnot just like a servant girl? Is the meaning of ‘domestic’ not the same as ‘servant’?”

Mr. Venkatesan joined the others in teasing Miss Philomena, but late that night he wrote away to eight American universities for applications. He took great care with the cover letters, which always began with “Dear Respected Sir” and ended with “Humbly but eagerly awaiting your response.” He tried to put down in the allotted blanks what it felt like to be born so heartbreakingly far from New York or London. On this small dead-end island, I feel I am a shadow-man, a nothing. I feel I’m a stranger in my own room. What consoles me is reading. I sink my teeth into fiction by great Englishmen such as G. A. Henty and A. E. W. Mason. I live my life through their imagined lives. And when I put their works down at dawn I ask myself Hath not a Tamil eyes, heart, ears, nose, throat, to adapt the words of the greatest Briton. Yes, I am a Tamil. If you prick me, do I not bleed? If you tickle me, do I not laugh? Then, if I dream, will you not give me a chance, respected Sir, as only you can?

In a second paragraph he politely but firmly indicated the size of scholarship he would require, and indicated the size of apartment he (and his sisters) would require. He preferred close proximity to campus, since he did not intend to drive.

But sometime in late April, the school’s porter brought him, rubber-banded together, eight letters of rejection.

“I am worthless,” Mr. Venkatesan moaned in front of the porter. “I am a donkey.”

The porter offered him aspirins. “You are unwell, sahib.”

The schoolteacher swallowed the tablets, but as soon as the servant left, he snatched a confiscated Zippo li...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- The Middleman

- A Wife’s Story

- Loose Ends

- Orbiting

- Fighting for the Rebound

- The Tenant

- Fathering

- Jasmine

- Danny’s Girls

- Buried Lives

- The Management of Grief