- 147 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Brief History of Memphis

About this book

The story of Memphis, Tennessee—from raucous river town to major Southern metropolis—with photos included.

No other southern city has a history quite like Memphis. First purchased in the early 1800s from natives to serve as a vital port for the emerging American river trade, the city flourished until the tumultuous years of the Civil War brought chaos and uncertainty.

Yet the city survived. Through the triumphs and tragedies of the civil rights movement and beyond, Memphis endured it all. Despite its compelling story, no concise history of this home of soulful music and unmistakable flavor is available to modern readers. Thankfully, local historian and Memphis archivist G. Wayne Dowdy has filled this gap with a history of Memphis that is as vibrant and welcoming as the city itself.

No other southern city has a history quite like Memphis. First purchased in the early 1800s from natives to serve as a vital port for the emerging American river trade, the city flourished until the tumultuous years of the Civil War brought chaos and uncertainty.

Yet the city survived. Through the triumphs and tragedies of the civil rights movement and beyond, Memphis endured it all. Despite its compelling story, no concise history of this home of soulful music and unmistakable flavor is available to modern readers. Thankfully, local historian and Memphis archivist G. Wayne Dowdy has filled this gap with a history of Memphis that is as vibrant and welcoming as the city itself.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Brief History of Memphis by G. Wayne Dowdy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

“TRICK OF THE PROPRIETORS”

In October 1818, elders of the Chickasaw Indian tribe sold more than 6 million acres of land to the United States. Included in the purchase was the Fourth Chickasaw Bluff, which was located on the Mississippi River in what would become the western district of Tennessee. Although the Chickasaw nation technically owned the property until 1818, this did not deter the State of North Carolina from claiming all land between its western boundary and the Mississippi River. Consequently, North Carolina officials gave some Chickasaw tracts to Revolutionary War soldiers and sold other parcels to pay state debts. One such piece of property was the Fourth Chickasaw Bluff, purchased from the State of North Carolina by John Rice. After Rice’s death in 1791, his heirs sold the grant to John Overton, who then shared parcels with Andrew Jackson and James Winchester. Despite owning legal title to the land, they could do little with it until the Chickasaw cessation of 1819.

With the sale complete, Jackson, Overton and Winchester wasted little time in organizing their property. Dividing the bluff into lots, the proprietors hoped to increase the area’s population through land sales, a stable government and expanded trade. This put them in direct conflict with many of the original settlers, or squatters, who did not own titles to their land and were fearful of being displaced by newer, wealthier arrivals. On November 24, 1819, the Tennessee legislature, acting on the proprietors’ wishes, established Shelby County, named for Revolutionary War hero and Kentucky governor Isaac Shelby.

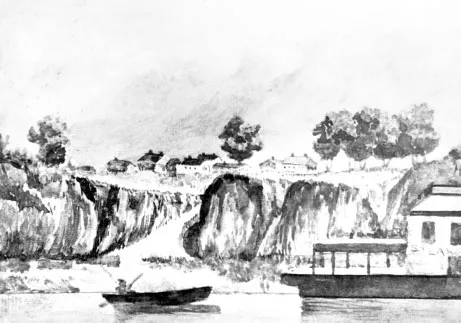

A view of Memphis not long after a German nobleman described the town as “a group of rather miserable houses.”

In the spring of 1820, Governor Joseph McMinn appointed six justices of the peace to administer local government in Shelby County. Among this group was James Winchester’s son, Marcus, who had arrived at the fourth bluff in 1818 to represent the interests of the proprietors. Born in Sumner County, Tennessee, Marcus Winchester joined the army during the War of 1812, in which he was captured by the British and held in a Canadian prison camp for several months. When Winchester arrived at the bluff, there was little to suggest that the area could become a trading metropolis. During the 1820s, Bernard, Duke of Saxe-Weimar Eisenach, traveled down the Mississippi River and was unimpressed by what he saw.

“Upon the fourth Chickesa [sic] Bluff…stands a group of rather miserable houses,” the German nobleman wrote in his book Travels Through North America During the Years 1825 and 1826. Recognizing the discontent brewing among some of the squatters, and wishing to appease them, the proprietors offered many of them titles to their land. This, however, did not satisfy the most strident member of the anti-proprietors faction, Isaac Rawlings.1

Rawlings had lived at the fourth bluff since March 12, 1814, when he was appointed by the federal government to run a trading post in order to “secure the friendship of the Indians in our country in a way the most beneficial and the most effectual and economical to the United States.” The majority of original settlers deeply respected Rawlings for his willingness to arbitrate local disputes and dispense justice without charging fees. In December 1826, when a shipment of Nashville newspapers arrived declaring that the state legislature had incorporated the bluff as the town of Memphis, the squatters turned to Rawlings in hopes that justice would again prevail.2

Sharing his neighbors’ view that high taxes would be an inevitable result of incorporation, Rawlings organized a public meeting to debate the incorporation charter. Many of the settlers denounced the measure, including one contrary soul who denounced it as a “trick of the proprietors.” Rawlings echoed this view when he rose to speak. According to historian O.F. Vedder, Rawlings explained to the audience—proprietors’ representatives and settlers alike—that “the town had not grown sufficiently in wealth and population to need a town government, and that its support would be a severe hardship on several of the poor people living in the outskirts of the proposed town.” Rawlings’s passionate argument convinced the proprietor faction to contract the town’s limits and exclude the poorest section of the bluff. This move did not eliminate the threat of taxation, but it nevertheless mollified many of the settlers, who tenuously accepted the new government.

The charter of incorporation created the office of mayor and a board of aldermen, to which was granted:

Full power and authority to enact and pass all bylaws and ordinances necessary and proper to preserve that health of the town; prevent [and] remove nuisances and to do all things necessary to be done by corporations; provided, none of the acts or ordinances shall be inconsistent with the laws and constitution of this state.

Aldermen were chosen by “all persons residing in said town, who are entitled to vote for members of the general assembly,” and the mayor was elected by the board of aldermen from within its membership. The first election was held on April 26, 1827, and several residents sought alderman positions, including Marcus Winchester. There was one notable absence on the list of candidates, however. Still smarting over the charter controversy, Isaac Rawlings refused to allow his name to be put in contention. N.B. Attwood, Joseph L. Davis, John R. Dougherty, G. Franklin Graham, John Hook and William D. Neely along with Winchester were chosen to serve as alderman; at the first meeting, Marcus Winchester was selected mayor.3

Once the mayor had been chosen, the major issue facing the aldermen was how to pay for the newly installed government. Taxes were assessed on property owners with improved lots, while peddlers, tavern keepers, physicians and attorneys paid a business levy for operating in the town. In addition, each free male inhabitant and slave were levied a twenty-five-cent tax for residing in Memphis. The first government also fixed the boundaries of the town and appropriated funds for street improvement. Reelected mayor the following year, Winchester oversaw the construction of a wharf that increased river traffic, expanded the town’s population and provided additional tax revenue in the form of wharfage fees. In his two years as mayor, Winchester effectively implemented the proprietors’ vision for Memphis; taxation led to street improvements and wharf construction, which in turn increased the town’s population and established it as a trading center. Indeed, by 1829, so much mail was passing through town that the U.S. Postal Department granted Memphis the same status as Nashville, which prompted the legislature to recognize the municipality as Tennessee’s second major town. This was no doubt gratifying to Winchester, but it also signaled the end of his public career. He had been serving as postmaster in addition to mayor, but the upgraded postal status forbade the local postmaster from holding other public office. Reluctantly, Winchester announced on the eve of the next scheduled election that he would not seek a third mayoral term.

Isaac Rawlings originally opposed the proprietors’ plans for the city but was later elected the second mayor of Memphis.

By 1829, Isaac Rawlings had reconsidered his decision to avoid involvement in local government. Consequently, he ran for, and won, a seat on the board of aldermen in the March 1829 town election. A vote was held at its first meeting, and Rawlings was selected mayor by a vote of four to three. As mayor, he abandoned the squatters and instead continued Winchester’s policies by improving streets and dividing the town into three wards, which expanded the size of the board of aldermen. Although reelected in 1830 and 1831, there were some in Memphis who never forgave Rawlings for switching sides and championing the proprietors’ cause.

In response, Rawlings attempted to eradicate the squalid neighborhood called Catfish Bay, located at the mouth of Gayoso Bayou. Labeling the neighborhood an “insufferable nuisance,” the aldermen introduced an ordinance to depopulate the area that Rawlings supported. Catfish Bay denizens, joined by newly arrived Irish immigrants living in the equally poor neighborhood known as the Pinch, denounced the nuisance ordinance as “a cruel, tyrannical infraction of the poor man’s rights, and a violation of the Constitution.” Ably assisting them in their fight with the aldermen was attorney Seth Wheatley, who successfully lobbied a majority to scrap the ordinance.4

The widespread support Wheatley received from Catfish Bay convinced the young lawyer to challenge Isaac Rawlings for an alderman seat. In March 1831, citizens from the impoverished neighborhoods flocked to the polls, where they repudiated Isaac Rawlings and elected Wheatley in his stead. When Rawlings learned that his former colleagues had chosen Wheatley as the next mayor, he allegedly determined to seek revenge on those who cost him his office. Two nights after the election, a boat filled with animal waste mysteriously floated into Catfish Bay and overturned. The stench emanating from the rancid waters soon turned the stomachs of the residents and forced them to flee.

Wheatley served only one term as mayor, as did Robert Lawrence, who was elected in March 1832. Soon after Lawrence’s selection, a census was taken that revealed that the population of Memphis had increased to 906 people. Recognizing this increase, the legislature expanded the town limits in October 1832. Many voters apparently longed for stronger leadership than Wheatley or Lawrence provided because in the municipal election of 1833, Isaac Rawlings was again elected to the board of aldermen and selected mayor. Reelected two more times, during his three additional terms Rawlings purchased a fire engine, which greatly improved the safety of Memphis.5

In addition to the fire engine, another expansion of town services came during the second administration of Mayor Enoch Banks, who served two nonconsecutive terms, 1836–37 and 1838–39. In August 1838, a board of health was appointed to “report to town constable all causes of disease the require removal and to arrange for the printing of death notices giving cause, name, and address in each instance.” The mayor who served between Banks’s two terms, John H. Morgan, also attempted to improve conditions in Memphis. During Morgan’s one-year term, the board of aldermen passed an ordinance requiring the operators of dray wagons to obtain a license for ten dollars per year, and if a driver was found guilty of “stealing or of having received stolen goods, he shall forfeit license and be thereafter prohibited from driving a cart, dray, or wagon within corporate limits.” A few months later, the aldermen passed a more stringent law that imposed “a penalty on persons shooting, whooping, gambling or swearing within the limits” of the town. Fines ranged from five dollars for swearing to ten dollars for discharging a firearm and fifty dollars for gambling—fees were doubled if the offense occurred on a Sunday.

Mayor Thomas Dixon, elected in 1839, expanded the anti-crime measures implemented by Morgan. Realizing that the constable could not patrol the town twenty-four hours a day, the board of aldermen hired two night watchmen, who were each paid $400 a year to patrol the town’s streets from 10:00 p.m. to daylight. Night watchmen had the authority to detain “disorderly” people, who could be fined for their offense, and compel any citizen to help them enforce the law. The aldermen also took steps to control the growing number of free persons of color and slaves living in, and navigating through, Memphis. Any African American, whether free or slave, who was discovered on the streets after 10:00 p.m. was automatically thrown in jail until morning. Detained slaves were then given ten lashes and their owners fined two dollars, while free blacks were fined ten dollars.6

Dixon and the aldermen also passed an ordinance requiring dog owners to buy a license and place an identification collar around the canine’s neck. If a dog was found without a collar, it would be summarily shot by the town constable. The town also purchased a larger fire engine, which could discharge 220 gallons of water per minute. Perhaps more importantly, on April 25, 1840, Dixon proposed an act to remove the town designation and adopt the name “City of Memphis,” which was supported by the aldermen. Despite Dixon’s considerable accomplishments in fighting crime and expanding city services, he was defeated for reelection by William Spickernagle in the spring of 1841.

For the first fifteen years of its existence, the office of mayor had few powers, was controlled by the board of aldermen and did not even pay a salary. This changed when the voters of Memphis ratified a proposal to pay the mayor $500 per year for his services, and the city’s charter was amended to allow for the direct election of the mayor. The awarding of a salary and bringing the office out from under the aldermen’s control provided Mayor Spickernagle with added influence, which he used to address perhaps the greatest problem facing Memphis government.

For many years, flatboat operators had refused to pay city fees when they docked at the city-operated wharf. A raucous and violent-prone lot under the best of circumstances, the river men violated local laws with impunity and were not shy about spreading terror through the streets of Memphis. Their refusal to pay severely restricted the ability of local government to provide services and implement needed improvements. One reason for this deplorable situation was the timidity of earlier wharf masters, who all too often knuckled under to the flatboat men. Determined to remedy this, Spickernagle hired James Dick Davis, a local painter and future Memphis historian, to serve as wharf master, offering him “twenty-five per cent of his collections and promised to stand by and sustain him.” In order to strengthen Davis’s hand, the mayor also formed two armed militia units to enforce the wharf master’s decrees. As a result of Spickernagle’s actions, wharfage fees soon filled the city’s treasury for the first time in years. So while the city treasurer counted the funds, the flatboat men seethed with rage over a measure they believed to be “onconstitutional.”7

Feelings of rage turned violent two months after Edwin Hickman defeated Spickernagle in the March 1842 municipal election. On a very hectic collection day in early spring, five hundred flatboats were docked at the wharf. As the day wore on, an irate boat owner named Trester brandished a spiked club and threatened to “comb the Memphis wharf master’s head.” When Davis arrived on the scene, Trester waved the cudgel in his face and loudly declared, “I cut this on purpose for you, and I am going to use it on you if you ever show your face here while I remain…I am the master of the landing.” As Trester’s rant reached its climax, Davis noticed that a large crowd had formed and was lustily cheering the boat owner’s defiance. Fearing for his safety, Davis left the wharf and met with Mayor Hickman, who issued a warrant for Trester’s arrest and ordered Constable G.B. Locke to serve it.

When Locke attempted to serve the document, Trester threatened him as well, so the constable turned to the militia. Captain E.F. Ruth and a dozen armed militiamen quickly dispersed the crowd as Trester and his crew hastily paddled their boats away from the wharf. Safe in the belief that he had escaped their wrath, the boat owner taunted the militia to open fire on him. Davis, Constable Locke, Captain Ruth and the armed volunteers boarded the city’s ferry and rowed toward Trester. Members of the military company watched as Davis, Locke and Ruth were clubbed to the deck as soon as they boarded Trester’s vessel. Enraged by what they saw, the volunteers opened fire, killing Trester immediately. Upon returning to the shore, a mob of armed boatmen swarmed the wharf area, but the crowd dispersed when met by equally armed citizens and militia. The decisive action taken by Mayor Hickman, Wharf Master Davis, Constable Locke and Captain Ruth broke the power of the flatboat men and secured an important revenue stream for the city, which improved dramatically the city’s overall economy.8

In 1841, during Spickernagle’s term, Congress appointed a commission to investigate and recommend a site for a freshwater naval yard somewhere in the Mississippi Valley. When the mayor and aldermen learned of this effort, they appointed their own committee to “draw up a memorial to the president of the United States, setting forth the claims of Memphis and the advantages she possesses for such an establishment.” It is not known whether this document had any effect on the subsequent choice, but the federal commission determined, after a tour of the Mississippi Valley, that the best location for the proposed naval yard was in Memphis at the mouth of the Wolf River. Mayor Hickman and the board of aldermen agreed to sell the property to the federal government for $25,000 on May 4, 1843, and the parcel was transferred to the federal government the following year. Although the navy yard never reached its potential and was abandoned in the early 1850s, nevertheless it drew attention to the economic potential of Memphis and the lower Mississippi Valley.

This became apparent in November 1845 when the city hosted the Southern and Western Commercial Convention eight months after Jesse Johnson Finley was elected mayor. Designed to advocate for the construction of public works such as roads, canals and railroads to improve the economy of the southern and western states, the convention was attended by 476 delegates from fifteen states. The highlight of the gathering was an address by former vice president John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, who urged the convention to pressure the federal government to improve navigation on the Mississippi because “congress has as undoubted a right as to protect and provide for the safety of our commerce on the ocean.” Despite its earnestness, the convention did not see any of its proposals come to fruition for the region. However, the delegates were able to lay the foundation for a railroad to be constructed between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mississippi River, which would have a profound effect on the futu...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Memphis’s Three Revolutions

- Chapter 1: “Trick of the Proprietors”

- Chapter 2: “The Utter Failure of the Municipal Government of Memphis”

- Chapter 3: “Without a Dollar of Cash in Her Treasury”

- Chapter 4: “A Beautiful City, Nobly Situated on a Commanding Bluff”

- Chapter 5: “Why Not Vote the Officials Out of Power?”

- Chapter 6: “We Cannot Stand Still”

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author