- 131 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

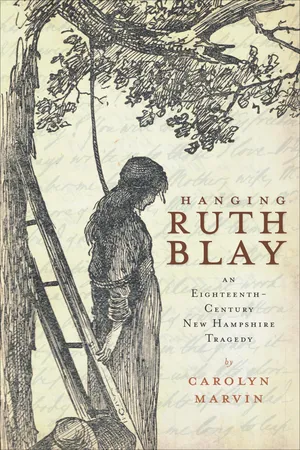

The true story of a woman hanged in colonial Portsmouth for burying her stillborn out-of-wedlock baby.

On a cold December morning in 1768, thirty-one-year-old Ruth Blay approached the gallows for her execution. Standing on the high ground in the northwest corner of what is now Portsmouth's old South Cemetery, she would have had a clear view across the pasture to the harbor and open sea.

The eighteenth-century hanging of a schoolteacher for concealing the birth of a child out of wedlock has appeared in local legend over the last few centuries, but the full account of Ruth's story has never been told. Drawing on over two years of investigative research, author Carolyn Marvin brings to light the dramatic details of Ruth's life and the cruel injustice of colonial Portsmouth's moral code. As Marvin uncovers the real flesh-and-blood woman who suffered the ultimate punishment, her readers come to understand Ruth as an individual and a woman of her time.

On a cold December morning in 1768, thirty-one-year-old Ruth Blay approached the gallows for her execution. Standing on the high ground in the northwest corner of what is now Portsmouth's old South Cemetery, she would have had a clear view across the pasture to the harbor and open sea.

The eighteenth-century hanging of a schoolteacher for concealing the birth of a child out of wedlock has appeared in local legend over the last few centuries, but the full account of Ruth's story has never been told. Drawing on over two years of investigative research, author Carolyn Marvin brings to light the dramatic details of Ruth's life and the cruel injustice of colonial Portsmouth's moral code. As Marvin uncovers the real flesh-and-blood woman who suffered the ultimate punishment, her readers come to understand Ruth as an individual and a woman of her time.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hanging Ruth Blay by Carolyn Marvin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

THE BEGINNING

I live in a cottage & yonder it stands

And while I can work with these two honest hands

I’m as happy as those that have houses and lands.9

–1737

Eighteenth-century provincial New Hampshire was a sprawling frontier wilderness run by British governors and magistrates. It was founded as a business venture rather than a haven for religious dissenters, and the population was originally clustered in the coastal centers of Portsmouth, Dover Point and Gosport at the Isles of Shoals. Captain John Smith’s early explorations in the 1620s produced maps that clearly showed the Isles of Shoals and Portsmouth, and by 1623 a fishing community existed at the Shoals.

Unlike the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay Colonies, where land was granted to a corporation, the area comprising Maine and New Hampshire was granted to individuals. In 1622, the British Council for New England granted the land between the Kennebec River in Maine and the Merrimac and sixty miles inland from their headwaters to Captain John Mason and Sir Ferdinando Gorges. They, in turn, “sub-granted” parts of this vast territory to others. Another man, David Thomson, had also secured a smaller grant of six thousand acres and, in 1623, sailed from Plymouth, England, with the backing of three Plymouth merchants to find a suitable site for settlement. Thomson and others sailed on the ship Jonathan and founded the first settlement in New Hampshire at Odiorne’s Point, at the mouth of the Piscataqua River.

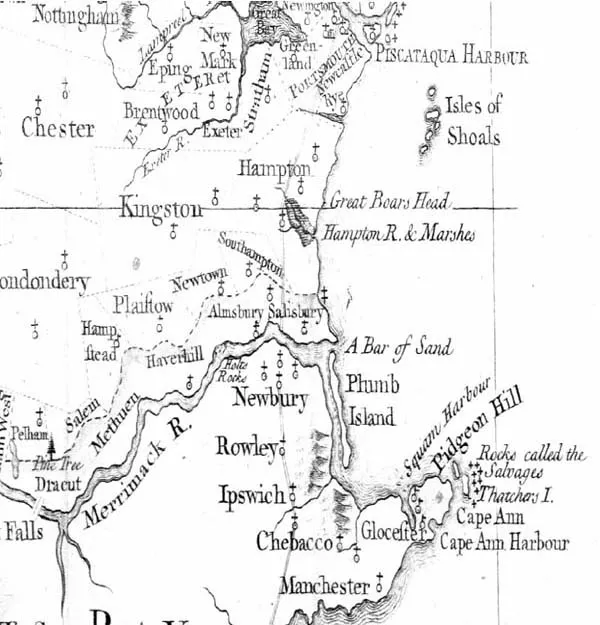

Detail from a 1761 map of New Hampshire as surveyed by Samuel Langdon, showing the towns in which Ruth lived, worked and died. Courtesy of the Portsmouth Athenaeum.

Following the Piscataqua and its branches, the Cocheco and Lamprey, settlers moved inland from the southeastern coast to found the towns of Dover, Durham, Exeter and others. Along the border with the Massachusetts Bay Colony, other settlers followed the Merrimac River inland, and New Hampshire’s population grew with a continuous migration of Massachusetts families seeking land, religious freedom or both.

A good example of the latter was the arrival in 1638 of John Wheelwright’s group of Puritan dissenters, the Antinomians, who founded the town of Exeter. John, a minister in Quincy and the brother-in-law of Anne Hutchinson, took issue with the Puritan leadership’s stand on his sister-in-law, was banished from Boston and then moved to Exeter.

Governing an area of many individual land grants proved difficult, and New Hampshire came under the governing body of the Massachusetts Bay Colony until 1680. From that date on, it had its own assembly and an appointed royal governor and/or lieutenant governor. By 1730, the provincial seat in Portsmouth was becoming wealthy from active trading in lumber, masts and fish. Those exports bought imports to sell, and the small coastal town grew and became home to many successful merchants, including members of the Wentworth family. The court system, too, was centralized in Portsmouth. New Hampshire was ready to be declared a political entity in its own right. When the boundary dispute between New Hampshire and Massachusetts was finally settled in 1741, Benning Wentworth was appointed the first royal governor of the new province of New Hampshire. Benning and his nephew, John Wentworth, who succeeded his uncle, remained in power until the outbreak of the American Revolution.

Meanwhile, north and west of Portsmouth, the bitter French and Indian Wars had introduced the colonists, albeit at a terrible cost, to the central and northern areas of New Hampshire and Vermont as they cut roads through to the Canadian border in pursuit of the enemy. The Peace of Paris in 1763 finally brought a close to the last of the French and Indian Wars. In another twelve years, alliances would alter, and the French would side with America in the revolt against British rule. Between the earlier wars, as each ensuing peace lessened the danger of Indian attacks, many colonists revisited, laid claim to and settled in these areas.

New generations of long-standing families who had settled in the parent towns along the coast and mouth of the Merrimac River acquired new property in the hills just a few miles inland, and family members ventured forth to establish these new townships, build meetinghouses in which to worship and raise new families to farm the land and create new communities. The land was hilly with rocky soil, the weather unpredictable and life a constant struggle lived under strict religious tenets as unforgiving as the land. Hard winters and summer droughts added to the homesteaders’ trials. In Joshua Coffin’s History of Newbury, Newburyport, and West Newbury—towns a short distance away from where Ruth grew up in the second parish of Amesbury (now Merrimac)—earthquakes and aftershocks are reported almost every year from the great one of 1727 through 1755 and thereafter.10

Order and status were established as leaders in each community emerged, were elected to responsible posts and fulfilled their elected or appointed duties. Families also brought with them the status of their birth families. As with all frontiers, migration north of the coastal communities brought hardworking persons of great esteem, as well as its share of those who were marginalized by reputation, bad luck, poverty or temperament. Despite the best efforts of church, town and Crown, there had always been those who could not or would not conform to accepted social mores or legal constraints.

The high mobility of our New Hampshire forefathers and foremothers often makes tracking these families a genealogical nightmare. Women like Ruth Blay, who didn’t marry, had no brothers and whose sisters became absorbed into the families of their spouses, become even more difficult to track. Their surname effectively disappears.

Ruth began life in one of the Massachusetts border towns and later moved inland to live and work in today’s New Hampshire towns including South Hampton, Danville and Sandown.

Fortunately, Ruth had grandparents who were among the earliest and most respected settlers of Newbury, Amesbury and Salisbury. Ruth’s grandfather was John Chase, a son of Aquila Chase, one of the original proprietors of Newbury. Ruth’s great-grandfather on her mother’s side was Philip Watson-Challis, another well-respected early settler in Salisbury and Amesbury. Her great-grandmother, Mary Challis, an apparently educated and independent woman for her time, administered Philip’s estate upon his death, and her name appears on a number of land transactions in her role as both family matron and executrix. It was Phillip and Mary Watson-Challis’s daughter, Lydia Challis, who would become Ruth’s grandmother. Lydia Challis and John Chase were married in 1687 in what must have seemed a most auspicious marriage, merging two of the most prominent family names in the area. In time, they became the parents of nine children whose births are recorded in the Newbury church records.11

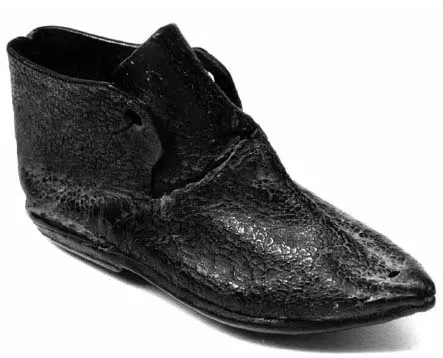

Example of an eighteenth-century child’s shoe, made by Samuel Lane of Stratham, New Hampshire. Ruth’s father, a cordwainer, would have produced similar shoes and other leather items. Courtesy of the New Hampshire Historical Society.

One of these children was Ruth’s mother, also named Lydia, who was born in 1700. Unlike her brothers and sisters, who married cousins or persons with surnames common to the area, Lydia seems to have chosen a relative “outsider” as her spouse, one William Blay of Haverhill, Massachusetts.12 Certainly he plied a respectable enough trade as a cordwainer (shoemaker), but he would have been of a lower economic class than Lydia, whose parents, while not wealthy, had certainly accumulated land, position and some material wealth, which can be ascertained from her father John Chase’s itemized will proved in 1739: “Item I give unto my daughter Lydia five shillings to be paid by my executor out of my estate after my Decease (the Reason why I give her no more is because she hath had her Portion already.”13

We can surmise that Lydia probably received the greater part of her “Portion,” whatever that may have been, at the time of her marriage to William in 1724, perhaps allowing them to establish their homestead in the eastern part of Haverhill known as Rocks Village. Seven children, all girls, were born to the couple, their births duly recorded in church records.14

The tragedy of losing children touched most eighteenth-century families, and the Blay family was no exception. Two children died in infancy during the 1735 “throat distemper” (diptheria) epidemic; a third died in 1747. Three of the girls would marry. The last born was Ruth, named for an infant sister whose death preceded her birth. A not uncommon practice, it has been the bane of many a genealogist since.

Lydia Blay was thirty-seven years old at the time of Ruth’s birth on June 10, 1737, an older mother by any standard. Baby Ruth’s siblings were Ann, six; Abigail, seven; Lydia, twelve; and eldest sister Mary, age thirteen. In England, George II had been in power for one decade and British-born American Patriot and pamphleteer Thomas Paine was born. In America, Jonathan Edwards published A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Works of God in the Conversion of Many Hundred Souls in Northampton, a work inspired by the beginnings of what would become known as the “Great Awakening.”

Chapter 2

TESTING THE FAITH

I Have a God in Heaven

Who Care For Me Doth Take

And If I to Him Constant Prove

He Will Not Me Forsake.15

–1737

In the middle of the eighteenth century, the faith and endurance of the Blays and others was greatly tested by renewed war against the French, culminating in the successful 1745 siege on Fort Louisburg in Cape Breton and two other major events: the outbreak of a serious contagious disease and the concurrent arrival and spread of religious fervor known as the “Great Awakening.” One of these we can prove had a direct effect on the young Blay family; the other we shall have to deduce may well have influenced the parents, if not the children.

The outbreak of “throat distemper” (diphtheria) was purportedly traced to the Clough farm in Kingston, where Mr. Clough had slaughtered a diseased hog in May. It then spread like wildfire throughout the surrounding communities:

The first person who took the disease was a Mr. Clough, who, having examined the swelled throat of a dead hog, died suddenly with a swelling in his throat…in fourteen towns in New Hampshire, nine hundred and eighty-four died between June, 1735, and July, 1736.16

The highly contagious disease took a devastating toll on the towns of southern New Hampshire, causing the death of over 1,000 persons, mostly children. In Haverhill alone, 199 persons died. The New England Weekly Journal for March 28, 1738, reported:

Just Published, the Second Edition, with Some Alterations and Additions, An Account of the Number of Deaths in Haverhill, and also some comfortable Instances thereof among the CHILDREN, under the late Distemper in the Throat; With an Address to the Bereaved. By the Rev. Mr. John Brown, Minister of the Gospel there.17

We can imagine that the Blay family, being among the bereaved, may have attended that sermon or at least read Reverend Brown’s published remarks. Their homestead was located on the eastern boundary of Haverhill, closer to Amesbury. In 1730, William was among twelve men who successfully petitioned the Haverhill church to release them to the second church of Amesbury (now Merrimac) so they might be closer to their meetinghouse.18 This was common enough in the eighteenth century, when pioneers may have established homesteads miles from the nearest meetinghouse and attending Sunday service, an all-day affair, was difficult and dangerous.

Regardless of whether the Blay family heard Reverend Brown’s accounting of the toll the throat distemper took, he and Lydia had suffered its devastation firsthand. A list of families who each lost two children includes the name of William Blay.19 The vital statistics of Newbury records their names: Ruth and Ealce. They died in 1735.

In May 1738 a pamphlet was published in Boston with verses c...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: The End

- Chapter 1. The Beginning

- Chapter 2. Testing the Faith

- Chapter 3. The Great Awakening

- Chapter 4. Home and Family

- Chapter 5. Semptsress and Teacher

- Chapter 6. A Fall from Grace

- Chapter 7. South Hampton Summer

- Chapter 8. Portsmouth: Summer of 1768

- Chapter 9. Politics and Penal Codes

- Chapter 10. King v. Blay

- Chapter 11. Hope and Despair

- Chapter 12. The Clough Connection

- Epilogue

- Ruth’s Story as Retold Through Time

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author