- 131 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hidden History of Boston

About this book

Quirky and little-known true stories of one of America's most historic cities.

Boston may play a big role in American history textbooks, but it also has quite a bit of forgotten past. For example, during the colonial era, riotous mobs celebrated their hatred of the pope in an annual celebration called Pope's Night. In 1659, Christmas was made illegal, a ban by the Puritans that remained in effect for twenty-two years. William Monroe Trotter published the Boston Guardian, an independent African American newspaper, and was a beacon of civil rights activism at the turn of the century. And in more recent times, a centuries-long turf war played out on the streets of quiet Chinatown, ending in the massacre of five men in a back alley in 1991.

Author and historian Dina Vargo shines a light into the cobwebbed corners of Boston's hidden history in this riveting read, complete with illustrations.

Boston may play a big role in American history textbooks, but it also has quite a bit of forgotten past. For example, during the colonial era, riotous mobs celebrated their hatred of the pope in an annual celebration called Pope's Night. In 1659, Christmas was made illegal, a ban by the Puritans that remained in effect for twenty-two years. William Monroe Trotter published the Boston Guardian, an independent African American newspaper, and was a beacon of civil rights activism at the turn of the century. And in more recent times, a centuries-long turf war played out on the streets of quiet Chinatown, ending in the massacre of five men in a back alley in 1991.

Author and historian Dina Vargo shines a light into the cobwebbed corners of Boston's hidden history in this riveting read, complete with illustrations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hidden History of Boston by Dina Vargo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

DO THEY KNOW IT’S CHRISTMAS?

The Banning of Christmas, 1659

Samuel Breck sat down to recount how Christmas was celebrated in Boston during his boyhood years, back around 1780. He came from an upper-crust family, and while his family was having a gathering, playing cards and chatting together, a group from the meanest class forced their way into his home. He described them as “disguised in filthy clothes and oftimes with masked faces”; the band of misfits demanded everyone’s attention by joining the card game, sitting on the furniture and generally making a nuisance of themselves. The only way to get rid of them was to give them some cash: “Ladies and gentlemen sitting by the fire. Put your hands in your pockets and give us our desire!”

Still not satisfied, the devilish crew then staged an impromptu play, acting out the death and revival of a reveler, right there in the midst of what had been a lovely evening for Breck and his friends. After about a half hour, the troupe disappeared, only for another group to come along and take their place, acting out a similar series of comic scenes and taking leave with a few coins.

A classic straight out of a Currier and Ives print this is not! Instead of a snowy sleigh ride and carols around a decorated tree, the Breck family holiday party was broken up by a ratty troupe of ruffians who disrupted their gathering, put on a play and then beat it out the back door with a mouthful of treats and a pocketful of the family silver, all before another merry gang came along to do it all over again.

This is not your typical idea of how early New Englanders enjoyed Christmas, but this kind of “celebration” is exactly why the Puritans banned it in the first place.

Puritans had a tense relationship with Christmas. As far as they were concerned, the exact date of the birth of Christ had never been determined, let alone confirmed. If Christ had been born on December 25, why wasn’t it written anywhere? The Puritans knew the Bible back and forth, and the date of December 25 is nowhere to be found. The Puritans knew the truth of the matter—as Christianity was emerging as a more widely accepted and practiced religion, church leaders also struggled to find the date of Christ’s birth. That led them to co-opt a popular pagan festival called Saturnalia. Call it killing two birds with one stone—undermine a pagan holiday and establish a Christian holy day. Celebrated at the Winter Solstice, at the end of harvest season and the start of a long, dark winter, Saturnalia was something of a bacchanal, a sort of spring break many months early.

During ancient Roman times, Saturnalia started on December 17 and continued until the twenty-third. During that period, gifts were given, feasts were attended and people were free to gamble and play dice games. The period was also marked by role reversals—slaves were allowed to eat with their masters, men dressed as women and vice versa. A Lord of Misrule was appointed to oversee the shenanigans, and obviously, no small amount of alcohol was consumed. “Moral excess” was the rule of the day, and it was not coincidental that a lot of babies were born nine months later.

Another tradition was also carried on. Akin to role reversals, the Saturnalia season, and later the Christmas season, was a time in which those with money helped the poor, so long as the poor literally sang for their supper. The singing was called “wassailing” or caroling. Mainly taken on by young boys, a group of kids would enter into a rich person’s home to sing for them and afterward be rewarded with food and money.

Even after Christians adopted Saturnalia as their own and called it Christmas, the rowdy traditions lived on all over Europe and in England. A pagan holiday called by any other name is still a pagan holiday, which is why the Puritans refused to observe it. And there was yet another reason why the Puritans rejected it—too much chaos, too much confusion and too much fun! In both England and New England, the Puritans were driven to purify the church, not pump up the volume. They removed all decoration from their churches and called them meetinghouses. They tried to control as much of their environment as possible and valued hard work, piety, learning and clean living. Before banning Christmas entirely, they tried to make it a fast day. We all know how that worked out long term, but the Puritans’ rejection of Christmas did affect those early American Christmases for much longer than the twenty-two years the holiday was actually illegal in Massachusetts.

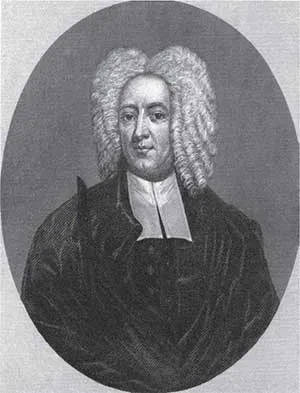

Cotton Mather was no fan of fun and frivolity. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. “Cotton Mather, D.D.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections, 1777–1890.

How did the Puritans celebrate Christmas? They didn’t. If Christ’s birth couldn’t be proven, there was truly nothing to celebrate. Work went on as usual, shops and stores stayed open, there were no special services, no meetinghouse bells ringing, no wreaths hung on doors or candles in windows. In New England, Christmas was just like any other day. It was those darned non-Puritans who ruined the party…by having a party.

The raucous traditions of Christmas traveled across the Atlantic to the colonies as more Anglicans made their way to New England. Caroling and singing in the streets, gambling, eating to excess, drinking, public drunkenness and the sexual conduct that accompanies all of the above were completely unacceptable behavior to the Puritans. To combat the revelry, in 1659, they took a page out of their brothers’ rule book in England (which had abolished the observance of Christmas in 1647) and banned the holiday. The ban must not have had the desired effect. Increase Mather wrote in 1687, “Men dishonor Christ more in the twelve days of Christmas then in all the twelve months besides.”

The ban was enforced with a five-shilling fine. It was accompanied by another law against taking any time off work to celebrate the holiday. No feasts were to be eaten, no carols sung, no playing of games and, clearly, no heavy drinking allowed. In a statement that seems to be reiterated by cultural pundits or Charlie Brown wondering about the true meaning of Christmas, Cotton Mather asked in 1712, “Can you in your conscience think that our holy savior is honored by mirth, by long eating, by hard drinking, by lewd gaming, by rude reveling…”

This ban against Christmas was in many ways more than what met the eye. The ban coincided with tension with England over the control of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. One could say that the ban of Christmas was an early shot across the bow of Britain in the long move toward independence. Indeed, in 1665, Charles II demanded that the ban on Christmas be lifted in New England to bring the colony more in line with British customs and traditions; Britain had abolished the ban in 1660. The ban was finally rescinded in 1681 under pressure from the Crown, but that did not mean that the Puritans started to observe Christmas.

There was an ongoing battle between the hated Governor Edward Andros, an Anglican appointed by the king, and the Puritans. Andros insisted on closing businesses on Christmas Day during his reign from 1686 to 1689. Later, as more Anglicans continued to arrive in Boston, it was something of a battle of wills to keep shops open on Christmas Day. The governors asked that leaders of the clergy encourage their parishioners to close shops, and both Cotton Mather and Samuel Sewall were among those who rejected the request. This was one way that the colonists could keep control over their day-to-day life under British rule.

The Reverend Samuel Sewell especially had a bone to pick against Christmas, writing constantly in his diary of those sinners who celebrated the holiday and how they did so. Whether it was a small French congregation or a newly ordained Anglican minister in Braintree, he observed and documented the transgressions.

Many years later, after the ban had been rescinded and Christmas was no more acceptable, the practice of mumming was taken up in Boston. Harkening back to the uproarious traditions of Saturnalia, mummers would disguise themselves and visit the homes of the well-to-do. “Visiting” might actually be too polite a term; mummers would barge into homes and make a nuisance of themselves. They would put on a short play and make a request of food or money. Those who participated were usually poor, and they cleverly called themselves the Anticks. From the 1760s into the 1790s, Boston’s finest families, like the Brecks, might entertain a visit from multiple groups of Anticks in the same night. At the time, tradition held that the well-to-do had to accommodate the groups of merrymakers, but later, these fine families started to complain and make their complaints public in the newspapers. Because of the outcry, police suggested that community members be free to make civilian arrests, after which the practice of mumming faded away.

By 1800, New England Unitarians had made their own play to subvert the pagan aspects of Christmas by making it an acceptable Christian holiday. Perhaps if it were a more respectable holiday, with the added sweetener of a day off work, people could be convinced to attend church to celebrate the birth of Christ and turn their back on the more crass aspects of the holiday. In 1817, a handful of Unitarian churches attempted to hold Christmas services and partnered with local businesses to close their doors, but by 1828, it was back to business as usual in Boston. Stores were open for business, and church doors were closed.

Again, we know how this story ends. Christmas is one of the most looked-forward-to Christian holidays that is often celebrated in some way by one and all, regardless of faith. Whether it’s the office holiday party (and Yankee Swap), just enjoying the Grinch on television or the music that becomes ubiquitous after Thanksgiving Day, Christmas season has become inescapable. And after all that the early New Englanders did to stop the celebration of Christmas in its sleigh-ride tracks, one of the cultural touchstones that popularized Christmas and made it much more accessible to families across America was developed by none other than a Bostonian. That touchstone is the giving and receiving of Christmas cards.

An extension of the traditional calling card, the holiday card was invented in England in 1843. By the 1850s, Christmas cards were being shared in America. A printer named Louis Prang, a German immigrant, seized upon the idea and turned a simple card into a huge industry. A postal official called it “Christmas card mania.”

Prang arrived in Boston in 1850. A wood engraver by trade, he worked for several printing presses until going off on his own in 1860. By 1868, Louis Prang & Company owned close to half of all steam presses in America. He was one of the best in the business, committed to using new technologies for better quality cards. He prided himself on introducing fine art to the American public in an affordable way. While other printers also sold Christmas cards, it was Prang who turned it into a massive enterprise. His cards were bigger and more “Christmas-y” than the cards created by his early contemporaries.

Prior to Prang’s involvement, Christmas card designs were Victorian in nature but lacked most indications we now associate with the holidays. The cards would feature flowers, children and birds. All lovely, to be sure, but it took Prang and his stable of (mostly female) artists to create the lexicon of the season—sleigh rides, evergreens and holly berries, carolers, families by the fireside, snowy churches and angels. Some of his most popular cards were fringed in silk, and overall, his cards were bigger and thicker than his competitors’. In this way, his cards could be offered as gifts in and of themselves. Indeed, Christmas cards didn’t wind up in the trash bin as quickly as they do today. Often the cards would be framed and hung in the home as artwork—such was both the sentiment and the quality of Prang’s product.

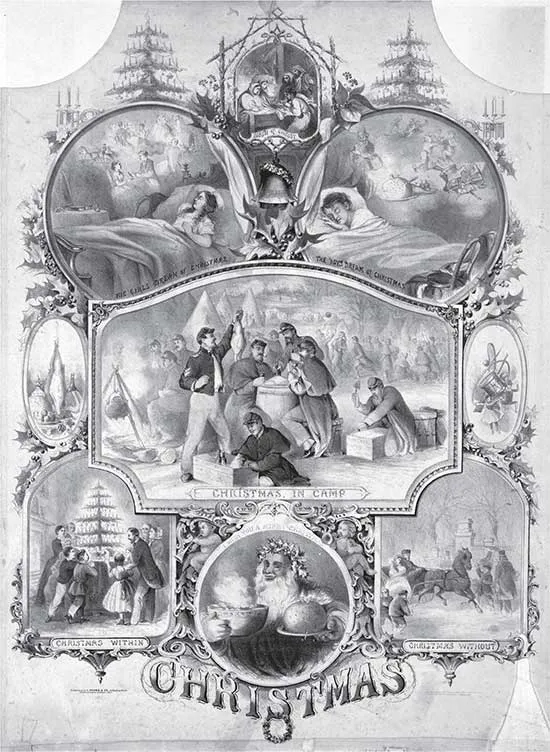

A Louis Prang Christmas card. L. Prang & Co., Christmas, 1862.

Of course, the overwhelming popularity of Christmas cards enabled other printers to enter the game and produce their own, with much less of a commitment to fine art and quality production and a stronger commitment to the bottom line. Prang, often hailed as the Father of the Christmas Card, continued on in his print company, producing fine art for public consumption, but eventually got out of the Christmas card business. Prang is buried in Forest Hills Cemetery, not too far from his factory in Jamaica Plain.

Chapter 2

AN AUDIENCE WITH THE POPE

Pope’s Night Celebrations, circa 1685–1774

John Poole hurried home. The sun had just set, and the chill November air spurred him to put some pep in his step. He usually enjoyed such evenings, breathing in the autumn air before the snow started to fly, but tonight, he wanted to get home, preferably behind locked doors. Trouble was brewing, as it had on this night every year since he could remember. He was all the more anxious because the violence was worsening. It used to be a bunch of street toughs battling it out for neighborhood turf, all in the name of good fun. Lately though, the fun had turned deadly. Just last year, a young boy was killed under the wheels of the North End mob’s cart, and the brawl had lasted all night long. Every year, the same ritual played out on the streets of Boston. The enemy wasn’t the rival street gangs; they were united against their common devil, the old Whore of Babylon. A fiery death for him was an issue on which almost all Bostonians could certainly agree.

Poole didn’t begrudge the fellas their fun, but he’d rather avoid a run-in. He’d done what he could to stay on the right side of the mob by donating a cask of rum for their festivities. Hopefully, they’d remember his deed and leave him and his family alone.

Poole continued his speedy cruise from the Long Wharf to home, but he could already see a crowd starting to gather—a drunken throng pushing and shoving at one another. He saw one member of the group point, and the horde gasped as they looked toward the North End. The procession had started. As he rounded the corner to get home, he could see the cart approaching with the most resplendent, beautifully decorated figure sitting atop it. Its robes flowed, caught in the evening breeze; its face was illuminated by the men carrying torches beside it. It wore a tall cap, decorated with bits of glass and ribbon that flickered in the night. Flanked by the horrible effigy of the horned Devil, which appeared to be dancing a jig, the crowd appreciated the artistry that had gone into making the dummy. Its twin, making its way to the center of town from the South End, was equally resplendent and terrible. Both would be consumed by bonfires by the end of the night—that was the way the Pope always ended his journey across Boston on the evening of November 5.

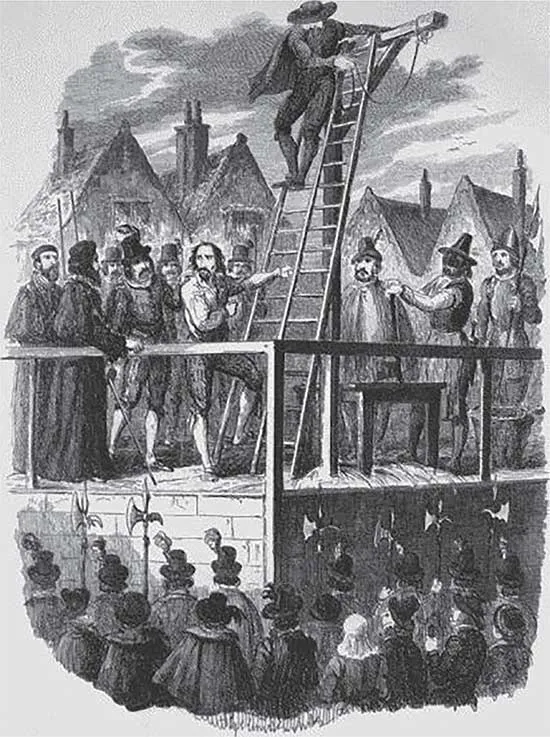

The brutal execution of Guy Fawkes. Made by George Cruikshank (1792–1878) in 1840 for a book titled Guy Fawkes or The Gunpowder Treason by author William Harrison Ainsworth.

Pope’s Night (also called Pope’s Day) was an annual celebration of anti-Catholic hatred. Celebrated every November 5 from roughly 1685 to 1774, the holiday had roots in Britain’s Guy Fawkes Night celebrations. Guy Fawkes was a Catholic who famously plotted to assassinate King James I by blowing up Parliament via a stockpile of gunpowder in its basement. He and his co-conspirators were caught on November 5, 1605. When they were found out, they were tortured to extract a confession to the so-called Gunpowder Plot. They were punished for treason by hanging to “near death.” As if that wasn’t enough, they were then “drawn and quartered,” meaning that each of their limbs and head was hacked off. Sometimes each limb would be attached to a different horse, and you can imagine the spectacle when each ran in a different direction. Occasionally, a little disembowelment and emasculation might be thrown in for fun, as the victims watched their own entrails be thrown into a raging fire—if they were conscious. Fawkes actually avoided this fate, succumbing to a much more humiliating one. He fell off the hangman’s scaffolding and broke his neck. Lucky break?

Meanwhile, across the pond, the holiday was especially popular in Boston because its citizens were particularly intolerant of Catholics and other religious groups in the colonial era compared to those in the other colonies. Why was this? Bostonians were Puritans, a religious group that wanted to go further than King Henry VIII had when he broke from the Catholic Church to found the Church of England. Puritans, both those in England and New England, are so named because their aim was to “purify” the Church of England—to make it more Protestant, less Catholic. Even today, some consider the Church of England to be “Catholic lite.” The Pilgrims, the group famous for the Mayflower, Thanksgiving and Plymouth Rock, wanted to go a step further and break away entirely from the Church of England. They were considered “Separatists.” It was the constant internal strife and battle for control for the English Crown between Protestants and Catholics that spurred the Pilgrims and Puritans to come to ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Do They Know It’s Christmas?

- 2. An Audience with the Pope

- 3. Night Shift

- 4. Burn, Baby, Burn

- 5. Fugitives to Freedom

- 6. Photogenic Phantasms

- 7. The Boy Torturer

- 8. Smallpox Smackdown

- 9. The Suitcase Case

- 10. Murder at the Y

- 11. Nevertheless, He Persisted

- 12. Fatal Plunge

- 13. Nightclub Nightmare

- 14. Soaring Social Worker

- 15. Monkeys and Cobras and Bears, Oh My!

- 16. Jew Hunting

- 17. The Tyler Street Massacre

- Bibliography

- About the Author