eBook - ePub

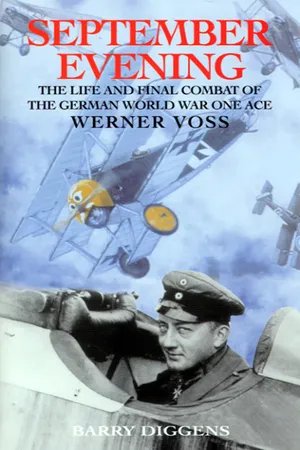

September Evening

The Life and Final Combat of the German World War One Ace: Werner Voss

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

September Evening

The Life and Final Combat of the German World War One Ace: Werner Voss

About this book

The true story of the daredevil flying ace who rivaled the Red Baron, with photos included.

This is the first full-length biography of nineteen-year-old Werner Voss, a legend in his lifetime and the youngest recipient of the Pour le Mérite, Germany's highest award for bravery in WWI. At the time of his death he was considered by many, friend and foe alike, to be Germany's greatest ace—and, had he lived, Voss would almost certainly have overtaken Manfred von Richthofen's victory total by early spring of 1918.

Voss is perhaps best remembered for his outstanding courage, his audacity in the air, and the prodigious number of victories he achieved before being killed in one of the most swashbuckling and famous dogfights of the Great War: a fight involving James McCudden and 56 Squadron RFC, the most successful Allied scout squadron.

Yet the life of Voss and the events of that fateful September day are surrounded by mystery and uncertainty, and even now aviation enthusiasts continue to ask questions about him on an almost daily basis. Barry Diggens was determined to uncover the truth, and September Evening unearths and analyzes every scrap of information concerning this extraordinary young man. Diggens's conclusions are sometimes controversial but his evidence is persuasive, and this study will be welcomed by, and of great interest to, the aviation fraternity worldwide.

This is the first full-length biography of nineteen-year-old Werner Voss, a legend in his lifetime and the youngest recipient of the Pour le Mérite, Germany's highest award for bravery in WWI. At the time of his death he was considered by many, friend and foe alike, to be Germany's greatest ace—and, had he lived, Voss would almost certainly have overtaken Manfred von Richthofen's victory total by early spring of 1918.

Voss is perhaps best remembered for his outstanding courage, his audacity in the air, and the prodigious number of victories he achieved before being killed in one of the most swashbuckling and famous dogfights of the Great War: a fight involving James McCudden and 56 Squadron RFC, the most successful Allied scout squadron.

Yet the life of Voss and the events of that fateful September day are surrounded by mystery and uncertainty, and even now aviation enthusiasts continue to ask questions about him on an almost daily basis. Barry Diggens was determined to uncover the truth, and September Evening unearths and analyzes every scrap of information concerning this extraordinary young man. Diggens's conclusions are sometimes controversial but his evidence is persuasive, and this study will be welcomed by, and of great interest to, the aviation fraternity worldwide.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access September Evening by Barry Diggens in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Storia militare e marittima. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

LEUTNANT DER RESERVE WERNER VOSS

(13.04.1897 – 23.09.1917)

Werner Voss was born on 13 April 1897 in the Rhineland mill town of Krefeld. Long famed for its quality silk and velvet manufacture, this ancient town still boasts a number of factories that continue a tradition of textile finishing that can be traced back to an influx of Mennonite cloth weavers who settled in the region during the 18th century. Some time in the 1890s, Max Voss, a wealthy industrialist and one of the town’s most respected citizens, married his childhood sweetheart Mathilde Pastor; a staunch Evangelical Lutheran who took her faith seriously. It has been intimated in several histories that the Voss family were non-practising Jews, but this has no foundation in truth, and though there was at least one Jewish family of the same name living in Krefeld during the 1930s they were not related to the subject of this book. Voss is a very common name for the region, and at the time of writing the Krefeld directory lists no less than eighty-five telephone numbers for residents named Voss.

Shortly after their wedding Max and Mathilde moved into a large, well-to-do house on Blumenthalstrasse, then a pleasant tree-lined avenue that like most of the town was sadly destroyed by Allied bombing during the Second World War. But before the turn of the century the couple had produced five lively children, two girls Margrit and Katherine, and three boys Werner, Otto and Max. Mother saw to it that they were brought up properly; church on Sundays and Bible readings before bedtime. As might be expected the Voss children enjoyed all the comforts of an affluent background. Their fortune stemmed from a highly successful cloth dyeing business, then situated on Geburstsstrasse, that still exists to this day, though now merged into a larger concern trading as Voss-Biermann Lawaczeck GmbH.

Werner was happy and carefree as a child, and often displayed a natural wit that was popular with everyone, but at times he could be headstrong and impetuous – characteristics that came to the fore during his military career. Afforded a good education at Krefeld’s Real Gymnasium, he did well as a student and passed several examinations with distinction. As the years passed he grew into a handsome young man of slim build, topped off with a mop of dark hair. Though not over tall, he had captivating blue eyes that from his early teens won the hearts of many a young Fraülein he chanced to meet in and about Krefeld. Unfortunately, the clouds of war arrested any possibility of his casual liaisons blossoming into long-term relationships, although there was talk of a young lady named Doris, who at some time may have figured large in his life and wrote a touching yet thought provoking letter to his mother in June 1918.

It was intended that the Voss boys would join the family business after completing their education, and no doubt they would have done so, but like so many impressionable young men of that hapless generation they were caught up in a wave of nationalistic fervour that swept through Europe like a tidal wave just prior to the outbreak of the Great War. In April of that fateful year of 1914, notwithstanding German conscription laws, Werner volunteered for his local militia, Ersatz Eskadron 2, a replacement unit for Westfälische Husaren-Regiment Nr. 11, then stationed at Paderborn. At the time the great alliances of Germany and Austria, opposed by Russia, France, and a less enthusiastic Great Britain, were busily stockpiling the powder kegs of war – and looking for an excuse to light the fuse. In April the French Ambassador to Austria wrote: ‘Feelings that the nations are moving towards conflict grow from day to day.’ In May a US envoy reported to President Woodrow Wilson: ‘Militarism runs stark mad … It only needs a spark.’ The spark came in June when a young Serbian anarchist assassinated the heir to the Austrian throne during a state visit to Sarajevo. Heated diplomatic exchanges flew back and forth between the capitals of Vienna and Belgrade and Austrian accusations were followed by demands, which in turn were followed by an impossible ultimatum to Serbia. Self-righteous Austria demanded retribution – but was refused. On 28 July 1914, with the full support of Imperial Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire declared war on the tiny Balkan state. Within a matter of days the continent of Europe became irrevocably embroiled in the greatest conflict the world had ever known.

When Germany mobilised Werner Voss was still only seventeen years old, but this did not stop him taking full enlistment in his active service regiment on 16 November 1914. Two weeks later Hussar Regiment No. 11 was ordered to the Eastern Front where, in contrast to fighting in the west, a war of movement was still being fought. However, like so many cavalrymen of that era, the young Rhinelander soon found himself fighting on foot. The battle fronts settled down, and as static warfare spread from the Baltic Sea to far off Galicia, the opposing armies were forced to dig-in. Unpleasant, muddy trenches, constantly swept by shell-fire and flying bullets, were not to his liking at all. Inclement weather only added to his misery and with the onset of that chilling winter of 1914 life in the firing line became particularly arduous. As on the Western Front, the war in the east degenerated into localised acts of attrition that daily took their toll on the men in the trenches. Despite the hardships, and no doubt fortified by the invulnerability of youth, Voss did his duty and distinguished himself in action on more than one occasion. On 27 January 1915 he was promoted to Gefreiter and by May he had been awarded his first decoration for bravery, the Iron Cross 2nd Class, which was quickly followed by a second promotion to Unteroffizier. But after ten months at the front, and by now feeling there could be no glory dying in a sea of mud far from home, he applied for a transfer to the Imperial German Air Service and was accepted. It is entirely possible that he actually engineered this move by getting himself classified as ‘unfit for further infantry and cavalry duties.’

His discharge from the Hussars finally came through, and on 1 August 1915 Voss reported to Flieger-Ersatz-Abteilungen Nr. 7 stationed at Cologne. FEA-7 was a training and replacement depot where recruits were put through a stiff induction course and assessed. Within a month he was recommended for pilot training and on 1 September presented himself at the conveniently located Fliegerschule at Eglesberg field – a wind-swept hill just outside his hometown of Krefeld. Here he proved to be an exceptional pupil, and after completing the course was returned to Cologne on 12 February 1916 to await posting to an operational unit. During the war, German aircrews underwent training at flying schools in Germany and were then returned to their depots for an orientation course that normally included several flights over the battlefront. They were then sent to an operational unit where they were expected to complete a certain number of combat sorties before being awarded their pilot’s badge. Werner Voss was no exception, though while languishing at the depot, eagerly awaiting his posting, he was employed as an instructor and at the tender age of eighteen had the distinction of being the youngest in the service.

Voss didn’t have too long to wait for the posting to come through. On 2 March he was promoted to Vizefeldwebel, and on the 10th assigned to a newly-formed fighting section, Kampfstaffel 20, which came under the aegis of Kampf-geschwader IV. The Kasta became operational on 28 March and he began his flying career as an observer on two-seaters in the Verdun sector. Here he was employed on bombing sorties, spotting for the artillery, and photographic missions that involved flying over one of the bloodiest killing-grounds in France: Mort-Homme, Fort Douaumont, Poivre Hill, and the dark waters of the Meuse as they gently meandered through the valley of the Argonne. It was a hot place to receive his initiation. General Philippe Pétain, then Commander of the French Armies of the Centre, charged the Aviation Militaire to clear the skies above Verdun; no German could be allowed to cross the lines. But constantly being harassed by anti-aircraft fire, and the often maniacal attacks pressed home by French fighting Scouts, soon taught Voss how to survive in the air. Finally, on 28 May, he received his coveted pilot’s badge and the Kasta was hurriedly moved up to the rolling downland of the Somme in preparation for the expected British offensive launched there on 1 July. Voss was glad to get away from the hell of Verdun, but there was to be no respite; he and his Kasta comrades experienced a harrowing time during the opening days of what was to be the long drawn out Battle of the Somme, a gargantuan struggle for a few yards of rain sodden French soil that lasted seven long months and claimed the lives of over half a million men. German observation and photo-reconnaissance machines took a terrific beating from the Royal Flying Corps during the early weeks of the struggle, and by the end of July the nineteen-year-old Vizefeldwebel was noted as the only original member of his unit to survive the intense air offensive mounted by the Allies.

Shaken by two-seater losses, Voss applied for a commission and was posted to the officer training college at Lochstadt Camp on the North Sea coast of East Prussia. Again, he did well and received his advancement on 9 September 1916. As a newly commissioned Leutnant der Reserve he was soon posted to the single-seat pilot’s training school, (Einsitzerschule) at Grossen-hain in Saxony, where he converted to fighting Scouts. His service record and family correspondence reveal that in early October he was then sent on a flying visit to Bulgaria, though the purpose of his brief stay there has never been explained.

On 21 November Voss was officially transferred to the most celebrated German fighting squadron of the day, Königliche Preussische Jagdstaffel Nr. 2, then stationed at Lagnicourt-Marcel on the Somme. This posting seems surprising. Jasta 2 had been formed in August 1916 under the leadership of the great Oswald Boelcke, an inspirationalist, brilliant tactician and experienced fighter pilot who, along with his contemporary Max Immelmann, became a national hero and one of the first great aces of the war. The son of a Saxon schoolmaster, Boelcke was known to his men as the ‘Master’ and eventually to the general public as the Father of the German Air Service. His series of critical reports, and an assessment of the air war prepared for Chef des Feldflugwesens (Chief of Field Aviation) Major Hermann von der Lieth-Thomsen, was instrumental in bringing together the most experienced pilots and loosely grouping them into single-seat fighter detachments known as KEKs (Kampfeinsitzer-Kommandos). Their brief was to achieve air superiority over hotly contested areas of the Front and to clear the skies of their Allied opponents in order to allow bombing and photo reconnaissance groups to go about their business unmolested. Although the concept was experimental, the outstanding success of the KEKs led to the formation of the first all single-seat fighter units, the Jagdstaffeln, seven of which were raised in the autumn of 1916. The Jagdstaffeln, commonly abbreviated to Jasta or Staffel, soon had at their disposal the most formidable German fighting Scout to come off the production lines, the Albatros D I, and shortly thereafter the variant D II. Power provided by a 160 h.p. Mercedes D-III engine enabled this relatively heavy aircraft to carry greater loads aloft than any other fighter of the day and also its two hard-hitting Spandau machine guns that were to reap a grim harvest among Allied two-seater crews in the spring of 1917.

For the most part, Jasta 2 pilots were handpicked, many by Boelcke himself. In the main they were either known to him personally or had been recommended by trusted friends and, without exception, were all men of experience or recognised fighting potential. Within weeks Boelcke had forged them into an elite, and the most successful fighting group at the Front. But by the time Voss arrived the ‘Master’ had been dead for just under a month, killed in an aerial collision with one of his own men on 28 October 1916. So, had the new commander of Jasta 2, Oberleutnant Stephan Kirmaier, chosen Voss, a young pilot with little experience on single-seaters, or was he previously known to Boelcke? This is a question that may never be resolved, though it is interesting to note that between March and July 1916 Boelcke had been on the Verdun Front with one of the first KEKs equipped with the infamous Fokker Eindeckers that had given the Allies considerable problems in the winter of 1915-16. Boelcke’s KEK had been stationed at Sivry in the Consenvoye sector, some three kilometres behind the lines, and was assigned the task of escorting two early bomber groups, BAO and BAM, acronyms for Brieftaube Abteilung Ostende and Brieftaube Abteilung Metz, better known as The Carrier Pigeons. The incongruous cover names were intended to fool the Allies into thinking these units were simply concerned with intelligence gathering, but it wasn’t too long before their true purpose was established. Voss’ own bombing group was attached to BAM during March and May, and Boelcke’s Eindeckers often flew with them. Which begs the question, did they actually meet, or was the Master simply apprised of Voss’ two-seater exploits by friends in Kampf-geschwader IV? The inclusion of a signed Boelcke portrait photograph among the few Voss papers that survived the Allied bombing of Krefeld in the Second World War, now held in the town’s Stadtarchiv, suggests that they did know each other.

Stephan Kirmaier succeeded Boelke as Staffelführer on 30 October, but survived only twenty-five days before being shot down over Lesboeufs by DH2s of 24 Squadron RFC – one day after Voss was officially assigned to the Staffel. The burden of leadership was then thrust upon Hauptmann Franz Josef Walz, an experienced thirty-one-year-old pre-war military pilot who took command of the unit on 29 November. Although recognised as a born leader by his superiors Walz was no Boelcke, and it wasn’t long before his ability to command the unit effectively was brought into question. In the meantime, Voss slotted comfortably into the flight commanded by one of the Master’s star pupils, an up-and-coming aristocrat and former Uhlan cavalryman, Leutnant Manfred Freiherr von Richthofen – and from this point their careers became inextricably linked.

Although the two airmen were at opposite ends of the social spectrum they soon became friends, for if nothing else Richthofen judged a pilot by his flying ability and fighting spirit and not by his station in life. It has been intimated in several histories that Voss and the soon to be christened ‘Red Baron’ never got on, and that this led to antagonism. This is improbable. There was indeed a certain rivalry between them, but this could only have been professional – or at worst one-sided. Though he was never in awe of the man, Voss respected Richthofen as a leader and accomplished tactician, and for his part Richthofen recognised a born air-fighter when he saw one. In this respect their abilities complimented each other: Richthofen went on to become a great leader of men and Germany’s highest scoring ace, but was never considered a great pilot – and while Voss went on to become possibly the greatest German fighter pilot of them all he was, by his own admission, never a great leader.

By mid-1917 the pair were household names, idolised by the German public, and unlike their British counterparts whose daring exploits were rarely publicised due to the RFC’s rigid policy of anonymity, they were fêted by the press and treated almost as equals. Although, after witnessing one of Richthofen’s victories over an outclassed two-seater, which had taken 600 rounds of precious ammunition to bring down near Givenchy-en-Gohelle, Voss wrote: ‘He is a great fighter and has done wonderful work for the Fatherland, but I do not believe that he is better than I am.’ It was said without undue pretension, as the cloth dyer’s son was well aware of his own limitations. There is no question that Voss thought Richthofen a close friend, and it is known that Richthofen reciprocated in some measure. Their friendship extended to sharing an interest in photography, and on more than one occasion they took leaves together that included visits to the Voss family home in Krefeld. Moreover, Richthofen had an open invitation to use the family’s hunting lodge in the Black Forest whenever he found time to indulge his passion for the chase – hardly a courtesy to be extended to someone disliked.

After the death of Voss, Richthofen continued his relationship with the family and there was talk that he and Werner’s younger sister Margrit were more than just fond of each other. It is possible that she (among other candidates) was the mysterious young woman who regularly wrote voluminous letters to Richthofen up until the time he was killed in April 1918. Lothar von Richthofen, Manfred’s younger brother, also kept in touch and regularly corresponded with Voss family members until after the war, as did other pilots and personnel of Jagdgeschwader Nr. 1. That Richthofen genuinely liked Werner Voss may be another matter. Curiously, he was seemingly kept at a distance, and Richthofen never mentioned his demise in any official capacity, yet he fairly eulogised two other star pilots of JG1: Karl Allmenröder, who in four months shot down thirty enemy machines but was killed in June by a pilot of the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS), and the thirty-three-victory ace Kurt Wolff, who was shot down in one of the first Fokker Triplanes to see service at the front – eight short days before Voss met his own nemesis. It is well known that Richthofen cultivated few real friendships during his career and that he remained aloof even to those he gathered around him. No doubt this was due to the realisation that friendship, like life itself, could be all too brief at the Front, and, having seen too many good men go west, he allowed few to get close to him. Voss and Richthofen were undoubtedly friendly rivals, but perhaps an element of jealousy had crept in somewhere, and this is possibly why he made no great play about the death of the young contender. Whatever the real reason, their true relationship remains something of a puzzle.

Hauptmann Walz followed the example set by Boelcke to the best of his limited abilities. Abilities that in fairness were only limited by the fact that he had little or no experience of commanding a fighter squadron – in reality he was a dyed-in-the-wool two-seater man with over 300 reconnaissance sorties under his belt. But now at Pronville, to where the Jasta had moved in December, he was like a fish out of water and found it difficult to adjust. Not unexpectedly his cautious behaviour and lacklustre battle tactics perplexed his pilots. Even so, he gave them a considerable degree of latitude, favouring personal initiative rather than regimented discipline, and allowed the more experienced to make lone forays across the lines. Scores continued to climb and, just a week after joining the squadron, Leutnant der Reserve Werner Voss began his mercurial rise to fame, fame that spread to both sides of the lines.

CHAPTER TWO

‘A DAREDEVIL FIRST CLASS’

(27.11.1916 – 23.09.1917)

By the autumn of 1916 aerial combats were commonplace, more so than in the previous two years of the war, and in the heat of battle it was not always possible for pilots to observe details of either the aircraft they were engaging or the results of a fight. This is illustrated by the intriguing controversies that surround Voss’ last combat. Conclusive proof of the outcome of engagements depended on witnesses, either in the air or on the ground. In fact the German criterion was particularly rigorous. Pilots were expected to provide a minimum of three corroboratory statements before victories could be confirmed by the office of Kogenluft and entered into the Abschusse, and even when such evidence could be produced errors inevitably occurred. On occasions this resulted in fanciful reports being accepted and recorded.

Understandably, in a full-blooded dogfight, a Scout pilot’s life depended on his ability to perform a continuing series of unpredictable turns and zooms, dives and banks; never holding to a straight line for more than a second. As the war progressed and more and more aircraft were pressed into service aerial combats often became a kaleidoscope of whirling machines darting about the skies missing each other by scant feet or even inches. In a dogfight there was ever present the dreaded possibility of a mid-air collision, which usually proved fatal. Allied airmen were denied the use of parachutes, and only in the last few months of the war were they employed by the Germans. In consequence, a pilot needed to have his wits about him just to avoid crashing into friend or foe, and once involved in a mêlée there was no time to take stock of aircraft as they flashed past, nor to note type or markings. There was but a moment to identify an opponent and to shoot as opportunities presented themselves. Unless a machine actually broke up in the air or burst into flames – definite proof that it would crash – there was little time to watch an aircraft falling out of control.

Confirmations were more of a problem for the Allies than the Germans. They were in fact at a considerable disadvantage. From very early on Allied pilots were charged to take offensive action on all occasions, a directive that was even extended to the hapless two-seater crews who rarely flew machines capable of a chase, much less a dogfight. Whereas, as a matter of policy the Jagdstaffeln, often equipped with superior aircraft, all but occasionally remained east of the lines in strategic defence. Not surprisingly, the majority of combats took place over German territory, euphemistically known to the British as Hunland, and this could be fifteen miles or more beyond the front lines. An added problem for the Allies was drift – something the Germans used to good effect – for on average eight days out of ten the prevailing winds blew out of the west. Embroiled in a fight, British and French pilots regularly found they were steadily drifting eastwards, whilst at the same time being drawn deeper and deeper into the German hinterland by their better-trained and often more experienced opponents. In these situations a pilot’s only course of action, if at all possible, was to disengage and head west, but it was doubly difficult for a damaged fighter or reconnaissance machine to reach the distant front lines and safety. In fights deep within their own territory the Germans had little difficulty establishing claims as they could usually rely on troops in the back areas and flak batteries that regularly reported combats and crash sites; whereas Allied pilots ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Chapter One Leutnant der Reserve Werner Voss

- Chapter Two ‘A Daredevil First Class’

- Chapter Three September Evening

- Chapter Four Aftermath

- Chapter Five Rumours of an Ugly Death

- Chapter Six Alternative Accounts and Conclusion

- Appendix I 56 Squadron Combat Reports

- Appendix II The 1942 Narratives of G.H. Bowman & R.L. Chidlaw-Roberts

- Appendix III Werner Voss – Service Record

- Appendix IV The Voss Victory List

- Appendix V Intelligence Reports on Fokker FI 103/17

- Appendix VI Where were the German Triplanes?

- Appendix VII The Voss Cowling and Triplane Camouflage Scheme

- Glossary

- Map of the Final Combat of Werner Voss

- Locations of the Voss Victories in the Arras Sector

- Locations of the Voss Victories in the Ypres Sector

- A Select Bibliography