- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"Turns out that what you thought you knew about Lady Liberty is dead wrong. Learn the truth in this fascinating account." —O, The Oprah Magazine

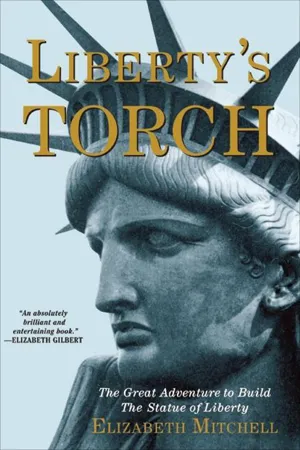

The Statue of Liberty is one of the most recognizable monuments in the world, a powerful symbol of freedom and the American dream. For decades, the myth has persisted that the statue was a grand gift from France, but now Liberty's Torch reveals how she was in fact the pet project of one quixotic and visionary French sculptor, Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi. Bartholdi not only forged this 151-foot-tall colossus in a workshop in Paris and transported her across the ocean, but battled to raise money for the statue and make her a reality.

A young sculptor inspired by a trip to Egypt where he saw the pyramids and Sphinx, he traveled to America, carrying with him the idea of a colossal statue of a woman. There he enlisted the help of notable people of the age—including Ulysses S. Grant, Joseph Pulitzer, Victor Hugo, Gustave Eiffel, and Thomas Edison—to help his scheme. He also came up with inventive ideas to raise money, including exhibiting the torch at the Philadelphia world's fair and charging people to climb up inside. While the French and American governments dithered, Bartholdi made the statue a reality by his own entrepreneurship, vision, and determination.

"By explaining Liberty's tortured history and resurrecting Bartholdi's indomitable spirit, Mitchell has done a great service. This is narrative history, well told. It is history that connects us to our past and—hopefully—to our future." — Los Angeles Times

The Statue of Liberty is one of the most recognizable monuments in the world, a powerful symbol of freedom and the American dream. For decades, the myth has persisted that the statue was a grand gift from France, but now Liberty's Torch reveals how she was in fact the pet project of one quixotic and visionary French sculptor, Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi. Bartholdi not only forged this 151-foot-tall colossus in a workshop in Paris and transported her across the ocean, but battled to raise money for the statue and make her a reality.

A young sculptor inspired by a trip to Egypt where he saw the pyramids and Sphinx, he traveled to America, carrying with him the idea of a colossal statue of a woman. There he enlisted the help of notable people of the age—including Ulysses S. Grant, Joseph Pulitzer, Victor Hugo, Gustave Eiffel, and Thomas Edison—to help his scheme. He also came up with inventive ideas to raise money, including exhibiting the torch at the Philadelphia world's fair and charging people to climb up inside. While the French and American governments dithered, Bartholdi made the statue a reality by his own entrepreneurship, vision, and determination.

"By explaining Liberty's tortured history and resurrecting Bartholdi's indomitable spirit, Mitchell has done a great service. This is narrative history, well told. It is history that connects us to our past and—hopefully—to our future." — Los Angeles Times

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Liberty's Torch by Elizabeth Mitchell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Our Hero Emerges from the Clay

Our Hero Emerges from the Clay

A sculptor first sketches an idea before he commits chisel to stone or bronze to a mold. When that sketch has been sufficiently rendered, the artist creates a model—the French word is maquette—usually in clay. One could say a maquette is the actual statue’s first true version.

Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi was preceded by his own maquette. In the Alsatian town of Colmar, France, the first Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi was born to Jean-Charles Bartholdi and his beloved wife, Charlotte, on September 24, 1831. His brother, one-year-old Jean-Charles, or Charles, already waited at home.

Frédéric unfortunately suffered from ill health and died at seven months. The Bartholdis then had a daughter who also passed away after only one month. More than a year later, on August 2, 1834, the second Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi was born. This Frédéric Auguste would grow up knowing that he was not the first Frédéric Auguste. This Frédéric Auguste replaced a boy who had vanished. His own maquette had disappeared.

Colmar, where Frédéric Auguste was born, is a charming town of narrow cobblestone streets, in the heart of Alsace in the northeastern part of France, not far from the German border. Its streets are lined with pastel homes sturdy with crisscrossed dark timbers that huddle at all angles against each other. Steep gabled roofs slope like bonnets, and in the eaves sometimes storks come to nest, symbols of good luck for the region. Shutters with cutouts of hearts and shamrocks swing open over window boxes filled with blossoms and vines.

Early in their marriage, Jean-Charles and Charlotte would stroll together in the evenings along these streets, across the small bridges that arched over the languid canal. The two had been deeply in love for years, and Charlotte would often grow anxious when Jean-Charles traveled for his work as a counselor to the prefecture (the regional office of the government). He would send her a stream of love letters and poems: “I have won a treasure, who will make happiness of my life,” “I am your servant, my dear Charlotte.”

As the daughter of a merchant, the former mayor of nearby Ribeauvillé, Charlotte had been educated in German and French, music and writing. Growing up, she was reputed to be the handsomest girl in Alsace, with gentle, lambent eyes. Eventually she would demonstrate a strong business sense. Yet something within Charlotte made her pine for those she loved with an emotion that bordered on the extreme, even in the days when life was peaceful.

These two families, joined in marriage, enjoyed high status in the town. Their lineage included preachers, government officers, and respected merchants. They socialized in a circle of artist friends. The mantel of their fireplace bore the legend “Blauer Himmel Über Uns”: “Blue Skies Above Us.” Their home, an elegant three-story domicile bordering a graceful courtyard on narrow rue des Marchands, felt blessed.

That is what made the conversation between Jean-Charles and Charlotte so peculiar on that summer day of 1835, as they strolled through Colmar together. A few years earlier, Jean-Charles had fallen ill with a disturbing but unnamed malady, and in a state of worry drafted a will. Should he die, he stated, he expected that Charlotte would not remarry; she would put her children’s welfare above all else. He half-scolded himself on those pages for expecting that outcome. But the illness had passed, and with it, discussions of wills or death.

That’s why it must have seemed strange that, without preamble, Jean-Charles asked Charlotte: “Since you like it so much here, don’t you want to try to walk alone? In this old world, you must be prepared and expect everything. Learn, I pray you, to be self-sufficient.”

The words chilled her, she would later report in a letter. Charlotte had thought her dear husband had gotten over his illness. This mysterious statement seemed a warning that he might vanish and she would have to continue on by herself.

Four days later, Jean-Charles fell ill. “This was the last of the most beautiful nights of my life,” Charlotte wrote.

Charlotte summoned doctors—first, a regular physician, and then a homeopath—to help her husband. Nothing worked, and she blamed the homeopathic treatments for worsening Jean-Charles’s condition and ruining his sleep, not allowing him even one full night of rest in the end.

On August 16, 1836, Jean-Charles died. Over a six-year period, Charlotte had lost two children and her one true love. Charlotte’s home was now empty but for her two children—ages seven and two, the “two marmosets,” as their parents had affectionately called them.

Jean-Charles’s revised will, which had been made out four months before his death, reconsidered the idea of Charlotte’s finding another husband after he was gone. He had decided that she might think it best to marry another in the pursuit of happiness, though if she did so, his fortune would pass to the children. If the second marriage were unhappy, his children were asked to welcome Charlotte and any children from her second marriage into their homes “even if she desires to take care of them, but especially not to let their mother want for anything, to give her an annual pension of three thousand francs, besides what she already owns, and to surround her and respect her with love. . . . I beg them, out of the love I have for them and the love they owe me, and if my prayers and orders in this regard would be ignored, they know that they will incur my fatherly curse.”

Charlotte threw herself with vigor into the raising of her sons. In a letter to Jacques-Frédéric Bartholdi, her late husband’s uncle in Paris, she outlined the differences between her two sons, characteristics that would flourish in their future selves. “They are very different both physically and mentally,” she explained, “and one cannot recognize them as brothers except for the mutual affection they have for each other. The ‘eldest’ [Charles] will be six the first of November, next Tuesday. He is not very big for his age, but for the past two years he has been in very good health. He has blond hair and blue eyes, and his light complexion makes him seem rather delicate. His figure is very sweet and open . . . this makes his instruction and education easy to navigate.

“He is excessively sensitive, and we will have to prepare him to know a lot of disappointment in the world. The good child cannot bear the weight of any idea of evil. One day we told him about a fable, the character and the habits of wolves. He finished by crying, ‘Mother, aren’t there also good wolves?’”

About Auguste, she wrote: “I will discuss the second child, who is two and a half years and three months old. His body is very strong and robust, and his eyes and complexion and hair are all black. He is a very good child, very talkative. His faculties are fairly developed for his age, but his character needs to be guided a little differently from that of the older child, it will be a little more difficult. This child seems to me to carry with him the seed of a man with a strong and resolved character. Sometimes, at this age, one would call that character trait stubbornness, so it will be a matter of shaping that character without crushing it.”

That she could see such nuances of personality in her sons at so early an age speaks to Charlotte’s intelligence and emotional understanding. Her assessment of Charles and, in particular, Auguste, at less than three years of age, would hold true the rest of their days. As Auguste grew up, he tried to appease Charlotte by proving that her investment in his future, the investment of her whole life, was worthwhile.

Shaping the character of her boys came to mean focusing intensely on their education in the arts. Charlotte arranged cello lessons for Charles and violin lessons for Auguste. She enrolled them in the new school that had been established by King Louis-Philippe’s government for boys in their village. They took drawing lessons from Martin Rossbach, a Colmar resident who had known their father well enough to paint his portrait before he died.

The town offered a respectable future for her boys, but the options for them there would be somewhat parochial. They could enjoy a pleasant life, but they would not be likely to make a great mark on the world. In Paris, Jacques-Frédéric Bartholdi enjoyed great prestige as the founder of a bank and fire insurance business. His son was married to Countess Louise-Catherine Walther, an aristocrat well connected in Protestant circles. The beau monde they occupied would have seemed extremely enticing to a widowed mother of two.

Paris offered dreams, but also danger. The French revolution had ended just before Charlotte was born, leaving behind the memory of half a million French citizens slaughtered across the country, including the guillotining of King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. The First Republic oversaw France’s governance for more than a half dozen tumultuous years, until Napoléon Bonaparte rose to power. Charlotte would have spent her youth hearing about the unfolding events of his imperial wars across Europe, Russia, Egypt, and the Caribbean, and his eventual downfall. The year of her son Charles’s birth, Louis-Philippe came to power. In the first years, the working classes revolted and Republicans tried to rise up against his regime. His forces slaughtered eight hundred at the barricades and he continued with his rule. The idea of revolutionary bloodshed in an unstable city was very real. Yet for a boy like Auguste, the child she considered destined for greatness, Paris afforded the greatest possibilities for achievement.

The family left for the capital in 1843, when Auguste was nine. Upon their arrival, the Bartholdis would have marveled at the immense, state-of-the-art Gare Saint-Lazare, and the Arc de Triomphe in its pristine splendor. Each landmark was less than a decade old. On Sundays, the Louvre was open to the general public. King Louis-Philippe had ordered improvements to the Palais des Tuileries and its garden, as well as construction of new bridges throughout the city. The Hôtel de Ville—Paris’s city hall—had swelled to four times its previous size.

Charlotte found a home for herself and her boys on rue d’Enfer, Hell Street, where in 1777 a house had been swallowed as the excavations of urban miners gave way. Rue d’Enfer stretched through Montparnasse, just down from rue du Fouarre, described in a guidebook as “one of the most miserable streets in Paris.” Nearby stood the Observatory, a building with a line painted across the floor to mark the terrestrial meridian between the north and south poles. On the roof, an anemometer read the wind and a pluviometer the rain.

Near the Bartholdi home was the Hospital of Found Children and Orphans. A little farther, across the Barrière d’Enfer, was St.-Jacques, the square where the guillotine had been erected. “Persons curious of inspecting the guillotine, without witnessing an execution,” a guidebook of the time advised, “must write to M. Heidenreich, 5 Boulevard St. Martin.”

For several weeks every other year, citizens of all classes crowded the Salon, an exhibition hosted by the Académie des Beaux-Arts, the illustrious school for male artists (women were forbidden). The widely distributed catalogs from the exhibit would essentially ordain which artists were notable at that moment, and the event itself became a spectacle. Vernissage—varnishing—came to mean an art opening because painters at the Salon would be shellacking their canvases, hung floor to ceiling in alphabetical order, up to the last moment.

In the Place de la Concorde an exotic, mysterious pillar had recently been installed, having journeyed from Luxor—a gift from Egypt. On its sides were depicted the fantastic machines that had been used in ancient times to create it. This obelisk reminded artists and explorers of what monumental creation man was capable of achieving. Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi would eventually feel its exotic pull, too.

In January 1844, Charlotte enrolled her boys in the city’s most prestigious secondary school, Lycée Louis-le-Grand, a massive temple of learning founded in the Latin Quarter in 1563. The expansive building was the alma mater of such luminaries as Molière, Voltaire, and none other than the most important cultural figure of the period, Victor Hugo.

Hugo was in his early forties but thought of as a “sublime infant,” as his writing mentor François-René de Chateaubriand had dubbed him—emotional, volatile, almost insane, but charming for his fervor. He was just twenty years old when in recognition of his first volume of poetry he received a donative from King Louis XVIII. He was granted a regular government-bestowed salary after the publication of his first novel and a parade of poetry and prose followed, capped with the monumental success of his Hunchback of Notre Dame in 1831. King Louis-Philippe granted him a peerage, the nation’s highest honor, allowing him to sit with the nation’s lords and decide the country’s fate.

Hugo could be readily recognized on the boulevards, with his pale, round face and thin, long hair parted to one side. He often wore a look of intense turbulence suggesting he would be quick to get into a brawl, should the need arise. He maintained a complicated stable of mistresses, including one who ended up going to prison for her adultery with him, while he managed to escape charges since peers enjoyed immunity. Hugo was seen as the ideal artist: committed to his craft and wedded to the epic of human life.

Here, at Lycée Louis-le-Grand, one might dream of becoming such a man. Auguste and Charles Bartholdi could meet other boys who would, either through their fathers or on their own, provide professional relationships that would last a lifetime. Auguste and Charles promptly distinguished themselves with their failings.

“To avoid punishing him too frequently, I am forced to isolate him often,” wrote one teacher about Auguste in his first year, “because he is always disturbing his classmates. . . . He pays no attention to the class exercises.”

Another instructor complained, “He is weak and unaccustomed to work. His memory needs to be exercised.” The teacher at least offered one consolation. “Other than that, there is no lack of good will or judgment.”

Auguste sketched exquisite cartoons of his teachers, who wondered if he might fare better living at the school, as most students did, instead of attending as a day student. Yet if he had gone to board at the lycée, he would have missed the extraordinary additional instruction Charlotte arranged in their home or in the nearby ateliers, the workshops, of Paris’s artists.

There Auguste received lessons from the same artists who exhibited at the Salon or whose work hung in the Louvre. The musician Auguste Franchomme—a friend of Mendelssohn, and the most famous cellist of the time—visited the Bartholdi house to provide music lessons. The Alsatian painter Eugène Gluck, one of the founders of the plein air movement, would spend time with the boys and discuss art. Auguste was given “sight-size” instruction, copying a sculpture or a model’s pose onto a canvas placed at a distance so that the object could be rendered at exactly the same size it appeared to the eye. He would be coached in how to use a feint of color or line to create false perspective.

In 1847 Charlotte sent Charles to the atelier of the celebrated painter Ary Scheffer. Auguste tagged along. Scheffer, a Dutchman, had set ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- LIBERTY'S TORCH

- Also by Elizabeth Mitchell

- LIBERTY'S TORCH

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Prologue

- Book I

- 1 Our Hero Emerges from the Clay

- 2 Bartholdi Down the Black Nile

- 3 The Khedive Refuses

- 4 War and Garibaldi

- 5 Paris in Rubble

- Book II

- 6 America, the Bewildering

- 7 The Workshop of the Giant Hand

- 8 Making a Spectacle

- Photo Insert

- 9 Eiffel Props the Giantess

- 10 The Engineer and the Newspaperman

- 11 The Blessing

- 12 Liberty Sets Sail

- 13 Pulitzer's Army and Other Helpers

- Book III

- 14 Liberty Unveiled

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Back Cover