Beginnings

from Country: A Continent, a Scientist & a Kangaroo, 2004

In late November 1975, I temporarily set aside work at the museum and set out to see my country. My friend Bill and I left Melbourne with a few dollars in our pockets, intent on circumnavigating the continent at the height of summer.

I had decided to use the trip to collect specimens of comparative anatomy. To this end, and blissfully unaware of the need for a permit even to touch a native animal killed on the roadside, my bike was equipped with a small strap-on esky behind the pillion seat, inside of which rattled a large and gruesome-looking defleshing knife. I had thought far enough ahead to decide that I would donate any specimens collected to the museum, but more immediate issues had evaded consideration.

We headed west for Adelaide and then Perth, and it was only when we stopped, roadside, beside my first intended specimen—a splendid male western grey as large as myself—and set to work with my knife, that it occurred to me that other travellers in the South Australian outback might find such activities unsettling. Almost as soon as the thought formed in my mind the rumble of an approaching car was heard and, suddenly embarrassed at the spectacle I presented, I walked briskly away from the prone roo, whistling into the air and trying to hide the 50-centimetre-long knife behind my back.

Ever tolerant, Bill agreed that we should camp nearby so I could perform the gruesome deed under the cover of darkness. After eating Irish stew from our billy I set out, parking my bike in front of the carcass with the headlight on so that I could see what I was doing. The job was made unduly difficult because I had neglected to sharpen my sabre, and after a long, bloodied struggle it became evident that to retrieve the all-important skull I would have to use the weight of the carcass to separate the neck muscles. Wet with blood and lurching under the full weight of the dead marsupial, I was so preoccupied that I didn’t hear the approaching rumble until it was too late. As the car accelerated past I glimpsed the family inside, horror-struck, mouths agape, staring at the frenzied bikie who was waltzing drunkenly with a disembowelled kangaroo on a lonely country road. As they disappeared into the distance I finally detached the head, after which I impinged on Bill’s good humour yet again by boiling it, to remove the flesh, in our all-purpose billy.

Although our route kept us close to the coast, the green fringe of the continent soon gave way to the muted colours of the interior. It is surprising how narrow that life-giving fringe is. Nowhere in Australia is far from the outback, and every centimetre of the country is touched at some time or other by its winds, dust and flies. The flat dry inland was an utterly unfamiliar landscape, and one for which we were ill-prepared, for the Guzzis were possibly the worst bikes to take on such a trip. Mine did not even have air filters, instead sporting elegant bell-mouths on its carburettors. But we didn’t care. We were nineteen, and we were free.

On the Nullarbor, nothing among the low blue-tinged bushes stretching to the horizon stood higher than my knees. The sun baked our skin and the mirage ate up the distance, creating a sense of going nowhere. For hour after hour there was nothing but a road and a line of power poles stretching in both directions—a scar through the blue-green of the saltbush—with no sign of life.

But life there was, for the locusts were swarming. The first we came across were tiny and struck our legs like bullets—painful even beneath leather boots. The next swarm, still wingless, was larger and could leap a little higher, but their bodies were softer. The lot after that had sprouted wings, and they struck anywhere. Driving into a locust cloud at 120 kilometres per hour was like driving into a living hailstorm. Any exposed skin was soon stinging with pain, and we struggled to see the highway ahead through visors smeared with the white and yellow fluid of squashed insects.

Then there was a sign: Head of the Bight. We followed the dirt track, fatigued as the heat and the stifling air caught up with us. We got off our bikes and walked a few metres to where the endless plain suddenly ceased, as if sliced by a sabre far sharper than my own.

After days of unvarying flatness the terror of the crumbling vertical cliff at our feet was compounded by the Southern Ocean, which raged with such force at its base that I could feel the shock of the waves through my boots. Its booms made me stumble involuntarily backwards to the heat, flatness and still air of the inland.

As we rode on we discovered other living things in that seemingly desolate landscape: an emu with a stately stride, a red kangaroo lying in the shade of an insignificant bush. Close to the Western Australian border, mounds began to appear. They marked the burrows of southern hairy-nosed wombats, and some of them were large enough to crawl down. I squeezed head-first into one, vainly hoping to spot a wombat, and was surprised at how cool it was inside. Another chance to venture further underground soon arose. Cocklebiddy Cave is a huge cavern lying beneath the Nullarbor Plain a little to the north of the road. We parked our bikes before clambering down to a yawning pit. It was an awesome space, cool and gloomy as a cathedral, but what fascinated me most was the scattering of small bones, mostly of native mice and rats, which had become extinct on the Nullarbor only thirty or forty years earlier.

We paused just east of Kalgoorlie to admire the knotted, greasy trunks of the gimlet gums, and strode over the thin crust of dried moss and lichen, which along with the last flowers of springtime suggested that this could sometimes be a gentle land. But now it was flat and dusty, the mallee a maze of uniformity where you could easily get lost. Among the knotted trunks we saw lizards and birds, and more of that subtle beauty that is so characteristically Australian—a warty grey mallee-root, a gum tree shedding its old bark in flakes and fine strips. Then, in a small clearing, we stumbled upon an arrangement of mouldering sticks on the ground, and some sturdier branches still standing. It was the remains of an ancient gunyah, though how long the bough shelter had lain decaying there we could not tell, nor could we fathom why an Aborigine had chosen that obscure place to rest. Certainly it was of a size to allow one person only in its shade.

Over the years the vision of that gunyah has frequently returned to me, and I’ve imagined a solitary Aboriginal hunter returning to it with a catch of rabbit-sized marsupials, to spend the night in comfort. For someone who had never met an Aborigine, and who had spent their life amid the European grandeur of Melbourne, that gunyah came as a deep shock, for it put my society in context and made the Aboriginal occupation of Australia a palpable, recent reality.

Australia’s Oldest Marsupial?

Australian Natural History, Spring 1985

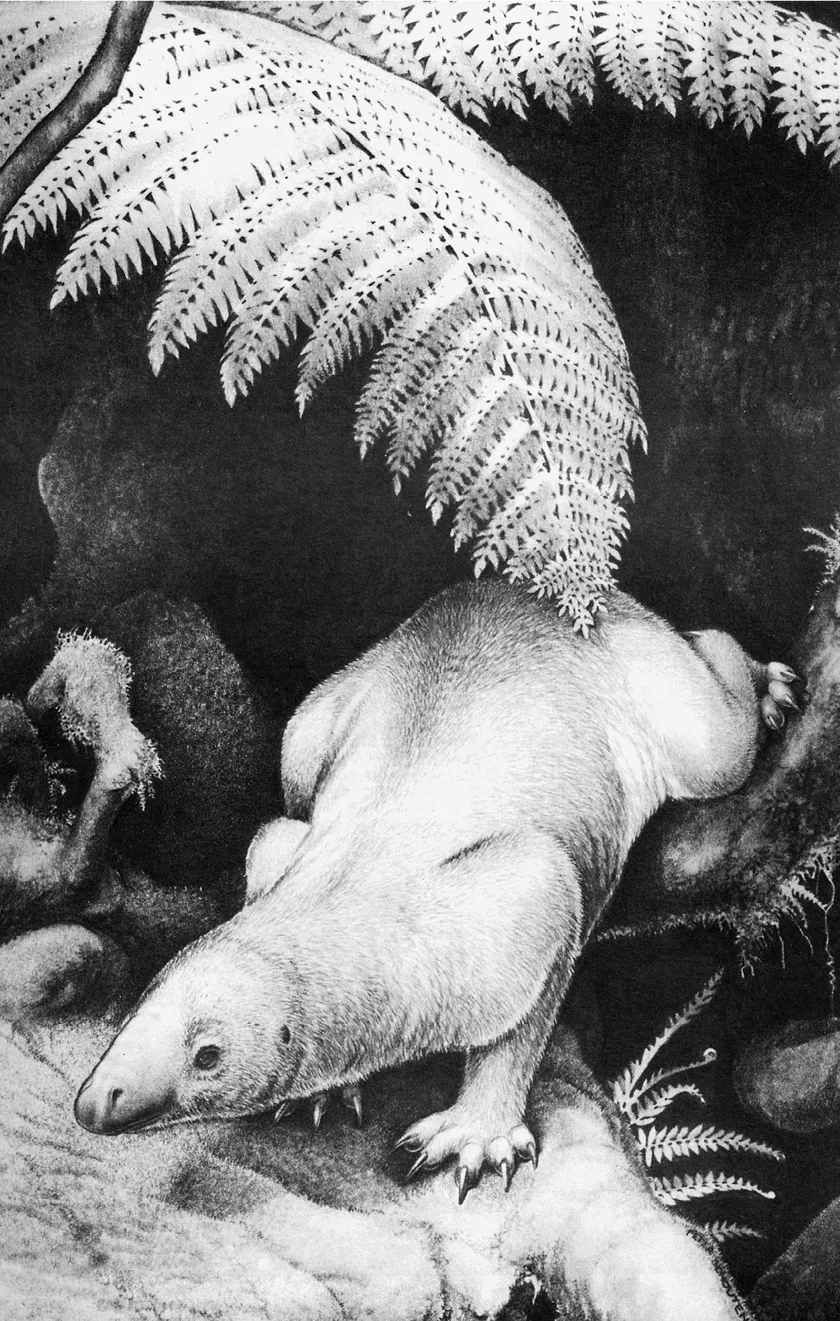

Reconstructing fossil animals is a great paleontological pastime. For many years adults and children alike have marvelled at the insights that reconstructions provide about the life of past epochs. There is, however, much misunderstanding about how such reconstructions are made. Indeed some creationists have been quick to exploit this misunderstanding and cite such works as attempts by scientists to mislead the public. The reconstruction presented here (drawn by Peter Schouten) is the result of considerable research and the story behind it illustrates how scientific reconstructions are made.

The most important thing to realise about this drawing is that it is a hypothesis; it is based as much on the inferred relationships of the fossil animal as it is on the actual fossil jaw fragment, containing three teeth, found at Lightning Ridge.

The group of paleontologists currently working on the Lightning Ridge mammal jaw agree that it represents a monotreme and that it probably belongs to a group of animals ancestral to the only living monotremes—the platypus and echidnas. This is the single most important piece of information used in guiding our reconstruction. Its importance lies in the fact that it indicates, in a very real way, that the Lightning Ridge animal is not extinct—it has simply changed. The living echidnas and platypus are the descendants of the group to which the Lightning Ridge fossil belonged. Thus its genetic material has been handed down, generation after generation for over 120 million years.

But how do we determine which features of the platypus and echidnas were present in their common ancestor (represented by the Lightning Ridge fossil) and which have developed since?

Some features of monotremes are unique among mammals and were presumably present in their common ancestor. These include the presence of a skin-covered bill, rich in nerve endings, and the presence of a spur on the hind foot. These structures are present in both the platypus and echidnas (although the bill is specialised in both forms). If they were not present in the common ancestor of both families, then we must assume that these otherwise unique structures were independently developed in both the platypus and echidnas. But this is highly unlikely and it is much more probable that these features were present in the ancestral monotreme.

This kind of deductive reasoning can be used to determine the probable nature of many aspects of our fossil beast. We have, for instance, used such information to reconstruct the snout, eye, ear, tail, stance and limbs of the Lightning Ridge mammal.

Of course there are aspects of the fossil mammal’s form that we cannot know. For instance, did it possess horns? It is possible that it did, but because all its descendants lack such structures we have no evidence for their existence and thus have not included them. And because we have not included features (such as horns) for which we have no data, this reconstruction is a conservative estimate of what the animal might have looked like. It includes only the features likely to have been present in the ancestral monotreme.

And what about the one piece of hard evidence that we have—the jaw fragment? All of our information about the animal’s relationships is of course derived from this specimen, and it also tells us the animal’s approximate size, a little about the shape of the snout and something of its diet. All of this information (except that relating to diet) is included in the reconstruction.

The reconstruction, therefore, represents a visual summary of the paleontologists’ knowledge of the animal’s relationships. The fossil jaw itself provides only a small piece of direct data used in the drawing. It is what the jaw tells us about the kind of animal that possessed it (in this case a primitive monotreme) that is important. Only with the discovery of more complete fossils can we rigorously test this hypothesis. It is clear, however, that alternative hypotheses could lead to different reconstructions.

Journey to the Stars

Australian Natural History, Spring 1987

In April 1987 a joint expedition from the Australian Museum and the Papua New Guinea Division of Wildlife filled in one of the few remaining ‘blank spots’ in our knowledge of the fauna of New Guinea. The expedition, consisting of myself, Hal Cogger an...