- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

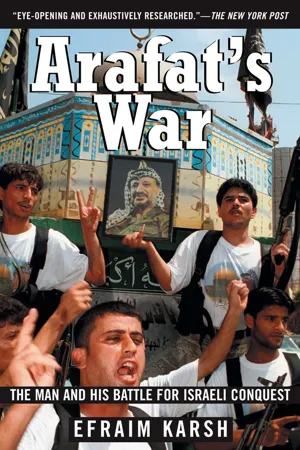

A noted historian analyzes Yasser Arafat's role in destabilizing the Middle East in a book praised as "eye-opening and exhaustively researched" (

New York Post).

Offering the first comprehensive account of the collapse of the most promising peace process between Israel and the Palestinians, historian Efraim Karsh details Arafat's efforts since the historic Oslo Accords in building an extensive terrorist infrastructure, his failure to disarm the extremist groups Hamas and Islamic Jihad, and the Palestinian Authority's systematic efforts to indoctrinate hate and contempt for the Israeli people through rumor and religious zealotry.

Arafat has irrevocably altered the Middle East's political landscape, and the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict will always be Arafat's war.

Offering the first comprehensive account of the collapse of the most promising peace process between Israel and the Palestinians, historian Efraim Karsh details Arafat's efforts since the historic Oslo Accords in building an extensive terrorist infrastructure, his failure to disarm the extremist groups Hamas and Islamic Jihad, and the Palestinian Authority's systematic efforts to indoctrinate hate and contempt for the Israeli people through rumor and religious zealotry.

Arafat has irrevocably altered the Middle East's political landscape, and the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict will always be Arafat's war.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Arafat's War by Efraim Karsh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Man and His World

If Arafat ever once stumbled and told the truth, he would say, “Please forgive me!”

—a close associate of Arafat, October 1996

It is an historical irony that the person who is arguably the world’s most famous Palestinian does not conform even to his own definition of what a Palestinian is. According to the Palestinian National Covenant, adopted in 1964 as one of the PLO’s two founding documents and revised four years later to remain the organization’s foremost article of faith to date, “Palestinians are those Arab residents who, until 1947, lived permanently in Palestine, regardless of whether they were expelled from it or have stayed there.”1

Born Muhammad Abdel Rahman Abdel Rauf Arafat al-Qudwa al-Husseini in Cairo on August 24, 1929,2 Arafat was the sixth child of Abdel Rauf al-Qudwa al-Husseini, a small textile merchant of Gazan-Egyptian origin, and of Zawda, a member of the Jerusalmite Abu Saud family. The couple had arrived in Cairo in 1927 and settled in the middle-class Sakakini neighborhood, where the young Arafat spent his youth. Aside from short stays, he never lived in Palestine prior to 1947, or for that matter at any other subsequent time, until his arrival in the Gaza Strip in July 1994 as head of the newly established Palestinian Authority (PA).

Throughout his career, Arafat has gone to great lengths to blur the circumstances of his childhood, especially the fact that his father was half Egyptian. When questioned about his birthplace, Arafat would normally claim to have been born and reared in the Old City of Jerusalem, just a few houses away from the Wailing Wall.3 Yet he has often contradicted himself. “I was born in Gaza,” he told Playboy magazine in September 1988. “My mother died when I was four and I was sent to live with my uncle in Jerusalem. I grew up there, in the old city. The house was beside the Wailing Wall. The Israelis blew up the house—demolished it in 1967 when they captured the city.”4 Whenever confronted with these contradictory versions and asked for a definite answer, his winning formula was that “my father was from Gaza and my mother from Jerusalem.”5

These claims, especially his connection to Jerusalem and the Israelis’ demolition of his alleged birth house, create a neat symmetry between Arafat’s personal biography and the collective Palestinian experience of loss and dispossession, despite both Arafat’s birth certificate and university records naming Cairo as his birthplace, as well as his strong Egyptian accent betraying a childhood spent in Cairo’s schools.6 Indeed, throughout his decades at the helm of the PLO, Arafat has never been able to overcome the widespread displeasure among the organization’s rank and file with his strong Egyptian accent. Dialects and accents constitute a central element of collective identity in Arab societies, not least among Palestinians with their persistent sense of loss and the attendant attempt to construct a national consciousness. Every Arab can detect, on the basis of dialect, accent, or intonation, his interlocutor’s regional origin, and Arafat’s accent leaves little doubt as to his Egyptian, rather than Palestinian, origin. Salah Khalaf (better known by his nom de guerre, Abu Iyad), Arafat’s close associate throughout their political careers, recalled his deep dismay at discovering, during their first meeting in Cairo in the 1950s, the heavy Egyptian accent of an aspiring chairman of the Palestinian student union.7 He wasn’t the only one to feel this way. When in the spring of 1966 Arafat was arrested by the Syrian authorities for involvement in the murder of a Palestinian activist, Abu Iyad rushed to Damascus, together with his fellow Fatah leader Farouq Qaddoumi, to secure his release. In a meeting with General Hafez al-Assad, then Syria’s defense minister, the two were confronted with a virulent tirade against Arafat. “You’re fooled that he is a Palestinian,” Assad said. “He isn’t. He’s an Egyptian agent.” This was a devastating charge, especially in light of the acrimonious state of Egyptian-Syrian relations at the time, and one that rested solely on Arafat’s Egyptian dialect. Yet for Assad this was a sufficient indictment. “You can go to Mezza [the prison] and take [him] away,” he said eventually. “But remember one thing: I do not trust Arafat and I never will.”8 Assad was true to his word until his death on June 10, 2000.

Such is the extent of Arafat’s sensitivity to his Egyptian origin that in his meetings with his subjects in the West Bank and Gaza, whom he has come to rule since the mid-1990s as part of the Oslo process, he is regularly accompanied by an aide who whispers in his ear the correct words in Palestinian Arabic whenever the chairman is overtaken by his Egyptian dialect.

Nor did Arafat take any part in the formative experience of Palestinian consciousness—the collapse and dispersion of Palestine’s Arab community during the 1948 war—in spite of his extensive mythmaking about this period. “I am a refugee,” he argued emotionally in a 1969 interview. “Do you know what it means to be a refugee? I am a poor and helpless man. I have nothing, for I was expelled and dispossessed of my homeland.”9

As a native and resident of Egypt, Arafat lost no childhood home in Palestine, nor witnessed any of his close relatives expelled and transformed into destitute refugees. As a Palestinian biographer of Arafat observed, “He was not a child of Al Nakba or the disaster, as Palestinians call the 1948 defeat, nor did his father lose the source of his livelihood.” Arafat himself complained to a close childhood friend, “My father didn’t leave me even two meters of Palestine.”10

Arafat’s bragging about his illustrious war record is equally dubious. One famous story involves the young Arafat stopping an attack by twenty-four Jewish tanks in the area that would come to be known as the Gaza Strip by knocking out the first and the last and trapping the others.11 Another story tells of Arafat being the “youngest officer” in the militia force of Abdel Qader Husseini, scion of a prominent Jerusalem family, whose death in the battle for the city in early April 1948 instantaneously transformed him from a controversial figure with a mediocre military record into a national hero.12 “I was in Jerusalem when the Zionists tried to take over the city and make it theirs,” Arafat is fond of saying.

I fought with my father and brother in the streets against the Jewish oppressors, but we were out-manned and had no weapons comparable to what the Jews had. We were finally forced to flee leaving all our possessions behind … My father gathered us—my mother, my brothers and sisters, our grandparents—and we fled. We walked for days across the desert with nothing but a few canteens of water. It was June. We passed through the village of Deir Yasin and saw what the Jews had done there—a horrible massacre. Finally we reached Gaza, where my father’s family had some land. We were exhausted and destitute. It was upon our arrival that I vowed to dedicate my life to the recovery of my homeland.13

Like other parts of Arafat’s biography, this account contains a mix of dramatic ingredients designed to transform his alleged personal experience into the embodiment of Palestinian history: a heroic but hopeless struggle against a brutal and superior enemy, a crushing defeat and the attendant loss and exile. Not only did the Israeli army have no tanks when this alleged incident took place (May 10, 1948), but according to another of Arafat’s own accounts he was in Jerusalem at the time and did not take part in the fighting in Gaza. As for Arafat’s alleged participation in the battle for Jerusalem, when asked whether he actually engaged in combat operations, he retorted angrily: “You are completely ignorant, I am sorry to say. You have no idea. The British army was still there with all its armaments. The main British forces were in Jerusalem.”14

With regard to the alleged escape of Arafat’s family to freedom, aside from telling two of his biographers that he had arrived in Jerusalem (in late April 1948) on his own, making no mention of other family members,15 the village of Deir Yasin was captured by Jewish forces in early April 1948, like most of the Tel Aviv–Jerusalem highway, and there was absolutely no way for Palestinian refugees to cross it on their flight. But even if some refugees had passed through the village in June, they would have found no traces of “the horrible massacre” that had taken place two months earlier. Had Arafat and his family really fled Jerusalem via the desert, as he claims, they would have gone in the opposite direction of Deir Yasin. But then the tragedy of Deir Yasin, where some one hundred people were killed in the fighting (the figure given at the time was more than twice as high), has become the defining episode of Palestinian victimization, and as such an obvious choice for appropriation by Arafat.

The truth is that while the Palestinian Arabs were going through the trauma of defeat and dispersal, Arafat “was completing secondary school in Cairo and did not stray far from the Egyptian capital during the great catastrophe.”16 He was of course as mindful as the next man of the unfolding Palestinian tragedy, but it is hard to say whether it affected him on a personal level, as he did not even do what thousands of non-Palestinian Arabs did—Egyptians, Syrians, Iraqis, and the like—and volunteer to fight in Palestine.

It was only natural for Arafat, by way of bridging the glaring gap between his personal biography and the wider Palestinian experience, to create a mythical aura around himself from his first days of political activity in the early 1950s at King Fuad University in Cairo. This was the only way he could compensate for his inherent inferiority vis-à-vis fellow Palestinian students, who really did arrive in Egypt as destitute and dispossessed refugees, and establish his credentials as a quintessential Palestinian, equal to the ambitious task of national leadership he had earmarked for himself. The higher he climbed, the greater was his entanglement in the intricate web of lies and fiction he had woven, steadily blurring the line between his own persona and that of Palestinian collective identity. In the words of two sympathetic biographers: “His own murky identity [is] a metaphor for all the Palestinians. He is the fatherless father, the motherless son, the selfless symbol of a people without identity, the ultimate man without a country.”17

This carefully contrived world of self-invention, where reality and fiction blend, was to become Arafat’s defining characteristic. He claims to have declined a studentship from the University of Texas in the early 1950s, but according to one biographer it is unlikely that he had ever been accepted given his poor command of the English language and the strict requirements at that time that foreign students have both a clean political slate and proof of the means to support themselves. He boasts of co-founding a construction company during his stay in Kuwait during the 1950s and the early 1960s, which made him a millionaire, while in actuality he was an ordinary civil servant who moonlighted in his free time, earning thousands rather than millions of dollars. His boasts of guerrilla exploits in the West Bank and Gaza in the months attending their occupation by Israel in the Six-Day War of 1967, where he was supposedly on the run from the Israeli authorities until early 1968, are dismissed by two of his biographers as being almost certainly an exaggeration.18

Arafat’s gift for invention extends well beyond his personal biography. Sometime in the mid-1970s, the Yugoslav president Josip Broz Tito, a staunch supporter of the PLO, sent a television crew to film a “model raid” on Israeli targets. Receiving the crew in Damascus, Arafat promised to lead the raid in person, asking the Yugoslavs to wait for him at a certain spot near the Lebanese–Israeli border. They waited there for two full days, only to return to Damascus empty-handed after Arafat failed to show.

Meeting the furious director again in his office, Arafat offered to stage a mock raid on the spot. He instructed the crew to start filming while he sat behind his desk shouting some orders. A number of young fighters dashed into the office and Arafat indicated to them certain areas on a huge map of Palestine, after which the fighters saluted him and left the room. When the filming was over, the director was beside himself with enthusiasm. “You’re a good actor, Chairman Arafat.” “I used to be, you know,” Arafat retorted.19

Even among Arafat’s admirers and followers he has been viewed as a congenital liar, so much so that in May 1966 he was suspended from his post as Fatah’s military commander for, among other things, sending “false reports especially in the military field.”20 “Arafat tells a lie in every sentence” is how a senior Romanian intelligence officer with whom Arafat worked closely described the PLO chairman, while one of Arafat’s intimate Palestinian associates has said, “If Arafat ever once stumbled and told the truth, he would say, ‘Please forgive me!’”21

Terje Larsen, a Norwegian academic who played an important role in the conclusion of the Oslo accords and who later became the United Nations special envoy to the Middle East, recalled an occasion when Arafat was attempting to persuade the Israeli foreign minister Shimon Peres that Peres had made a specific commitment to him:

Arafat said, “You told me on the phone—” Peres said, “No.” Arafat said, “Yes, you said so. Larsen was there in my office. And Mr. Dennis [Ross]” (U.S. peace mediator). “Larsen, you are my international witness. Mr. Peres, I have an international witness!” Everyone else in the room knew that this was untrue.22

The American-Arab academic Edward Said had a similar experience some fifteen years earlier when he passed on to Arafat the U.S. administration’s offer to recognize the PLO in return for the latter’s implicit acquiescence in Israel’s existence.

[I]n March of 1979 I flew to Beirut and went to see Arafat. I said to him, We need an answer. The first thing he said was, I never received the message. So for at least ten minutes he began to deny that any message came. Luckily, Shafiq al-Hout [director of the PLO’s Beirut office] was sitting with us in the room and he said, I delivered the message to you. Arafat said, I have no recollection of it. Shafiq went into the next room and brought a copy of it. Arafat looked at it and said, All right, tomorrow I’ll give you my answer.23

Others had a less cavalier attitude toward Arafat’s inability to tell the truth. Shortly after the signing ceremony on the White House lawn on September 13, 1993, Jordan’s King Hussein informed the Rabin government that Arafat was certain to violate the peace agreement he had just signed. “Israel is doing business with the worst possible person,” read a royal message. “Arafat has proved time and again that his word cannot be trusted.” Since the late 1960s, King Hussein had reached numerous agreements with Arafat only to see each and every one violated by his partner. “I and the government of the kingdom of Jordan hereby announce that we are unable to coordinate politically with the PLO leadership until such a time as their word becomes their bond, characterized by commitment, credibility, and constancy,” a somber Hussein stated in an address to the nation on February 19, 1986, shortly after being duped yet again by Arafat.24

President George W. Bush has had a far shorter relationship with Arafat than the deceased Jordanian monarch. Yet when in early 2002 he was reassured in writing by the chairman that he had had nothing to do with a ship carrying some fifty tons of prohibited weapons, purchased by the Palestinian Authority from Iran, despite conclusive evidence to the contrary, Bush appeared to have joined the list of world leaders profoundly disillusioned with Arafat’s credibility.

For decades Arafat has consistently engaged in a pattern of deceit as Europeans, Arabs, and even Israelis have been willing to indulge him despite the blatant transparency of many of his lies. Even the most incredible falsehoods, such as accusing Israel of carrying out suicide bombings perpetrated by Palestinian terrorists, assassinating its own minister of tourism in the winter of 2001, and murdering Arab children to get their organs, have failed to dent Arafat’s imagined identity.25

This pattern of deceit has also allowed Arafat to disguise another major issue of his personal identity. As he rose to public attention in the late 1960s, Arafat’s personal life came under increasing scrutiny. Not only had he not married and established a family like most of his fellow terrorists but, since adolescence, he had never been seen publicly with a woman in romantic circumstances, let alone been associated with one on a lasting basis. This has given rise to persistent speculation about his potential homosexuality. According to one of his siblings, Arafat was mercilessly taunted, as early as age three or four, by his peers and by his father for what they viewed as his girlish demeanor.

At this time in his life Rahman [i.e., Yasser] was fat, soft, ungainly and completely unimpressiv...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 The Man and His World

- 2 The Road to Oslo

- 3 A Trojan Horse

- 4 A License to Hate

- 5 Hate Thy Neighbor

- 6 Terror Until Victory

- 7 Eyeless in Gaza

- 8 The Tunnel War

- 9 Showdown in Camp David

- 10 Countdown to War

- 11 Why War?

- 12 Violence Pays

- 13 The Turning of the Tide

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Select Bibliography

- Index