eBook - ePub

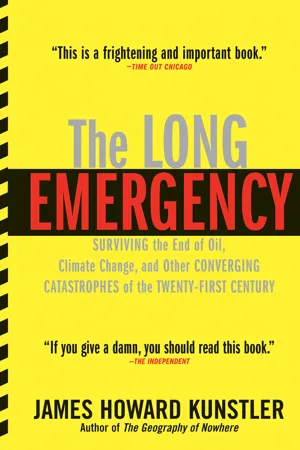

The Long Emergency

Surviving the End of Oil, Climate Change, and Other Converging Catastrophes of the Twenty-First Century

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Long Emergency

Surviving the End of Oil, Climate Change, and Other Converging Catastrophes of the Twenty-First Century

About this book

A "frightening and important" look at our unsustainable future (

Time Out Chicago).

A controversial hit that has sparked debate among business leaders, environmentalists, and others, The Long Emergency is an eye-opening look at the unprecedented challenges we face in the years ahead, as oil runs out and the global systems built on it are forced to change radically.

From the author of The Geography of Nowhere, it is a book that "should be read, digested, and acted upon by every conscientious U.S. politician and citizen" (Michael Shuman, author of Going Local: Creating Self-Reliant Communities in a Global Age).

A controversial hit that has sparked debate among business leaders, environmentalists, and others, The Long Emergency is an eye-opening look at the unprecedented challenges we face in the years ahead, as oil runs out and the global systems built on it are forced to change radically.

From the author of The Geography of Nowhere, it is a book that "should be read, digested, and acted upon by every conscientious U.S. politician and citizen" (Michael Shuman, author of Going Local: Creating Self-Reliant Communities in a Global Age).

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

ONE

SLEEPWALKING INTO THE FUTURE

Carl Jung, one of the fathers of psychology, famously remarked that “people cannot stand too much reality.” What you’re about to read may challenge your assumptions about the kind of world we live in, and especially the kind of world into which time and events are propelling us. We are in for a rough ride through uncharted territory.

It has been very hard for Americans—lost in dark raptures of nonstop infotainment, recreational shopping, and compulsive motoring—to make sense of the gathering forces that will fundamentally alter the terms of everyday life in technological society. Even after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, that collapsed the twin towers of the World Trade Center and sliced through the Pentagon, America is are still sleepwalking into the future. We have walked out of our burning house and we are now headed off the edge of a cliff. Beyond that cliff is an abyss of economic and political disorder on a scale that no one has ever seen before. I call this coming time the Long Emergency.

What follows is a harsh view of the decades ahead and what will happen, in the United States. Throughout this book I will concern myself with what I believe is happening, what will happen, or what is likely to happen, not what I hope or wish will happen. This is an important distinction. It is my view, for instance, that in the decades to come the national government will prove to be so impotent and ineffective in managing the enormous vicissitudes we face that the United States may not survive as a nation in any meaningful sense but rather will devolve into a set of autonomous regions. I do not welcome a crack-up of our nation but I think it is a plausible outcome that we ought to be prepared to face. I have published several books critical of the suburban living arrangement, which I regard as deeply pernicious to our society. While I believe we will be better off living differently, I don’t welcome the tremendous personal hardship that will result as the infrastructure of that life loses its value and utility. I predict that we are entering an era of titanic international military strife over resources, but I certainly don’t relish the prospect of war.

If I hope for anything in this book, it is that the American public will wake up from its sleepwalk and act to defend the project of civilization. Even in the face of epochal discontinuity, there is a lot we can do to assure the refashioning of daily life around authentic local communities based on balanced local economies, purposeful activity, and a culture of ideas consistent with reality. It is imperative for citizens to be able to imagine a hopeful future, especially in times of maximum stress and change. I will spell out these strategies later in this book.

Our war against militant Islamic fundamentalism is only one element among an array of events already under way that will alter our relations with the rest of the world, and compel us to live differently at home—sooner rather than later—whether we like it or not. What’s more, these world-altering forces, events, and changes will interact synergistically, mutually amplifying each other to accelerate and exacerbate the emergence of meta-problems. Americans are woefully unprepared for the Long Emergency.

Your Reality Check Is in the Mail

Above all, and most immediately, we face the end of the cheap fossil fuel era. It is no exaggeration to state that reliable supplies of cheap oil and natural gas underlie everything we identify as a benefit of modern life. All the necessities, comforts, luxuries, and miracles of our time—central heating, air conditioning, cars, airplanes, electric lighting, cheap clothing, recorded music, movies, supermarkets, power tools, hip replacement surgery, the national defense, you name it—owe their origins or continued existence in one way or another to cheap fossil fuel. Even our nuclear power plants ultimately depend on cheap oil and gas for all the procedures of construction, maintenance, and extracting and processing nuclear fuels. The blandishments of cheap oil and gas were so seductive, and induced such transports of mesmerizing contentment, that we ceased paying attention to the essential nature of these miraculous gifts from the earth: that they exist in finite, nonrenewable supplies, unevenly distributed around the world. To aggravate matters, the wonders of steady technological progress under the reign of oil have tricked us into a kind of “Jiminy Cricket syndrome,” leading many Americans to believe that anything we wish for hard enough can come true. These days, even people in our culture who ought to know better are wishing ardently that a smooth, seamless transition from fossil fuels to their putative replacements—hydrogen, solar power, whatever—lies just a few years ahead. I will try to demonstrate that this is a dangerous fantasy. The true best-case scenario may be that some of these technologies will take decades to develop—meaning that we can expect an extremely turbulent interval between the end of cheap oil and whatever comes next. A more likely scenario is that new fuels and technologies may never replace fossil fuels at the scale, rate, and manner at which the world currently consumes them.

What is generally not comprehended about this predicament is that the developed world will begin to suffer long before the oil and gas actually run out. The American way of life—which is now virtually synonymous with suburbia—can run only on reliable supplies of dependably cheap oil and gas. Even mild to moderate deviations in either price or supply will crush our economy and make the logistics of daily life impossible. Fossil fuel reserves are not scattered equitably around the world. They tend to be concentrated in places where the native peoples don’t like the West in general or America in particular, places physically very remote, places where we realistically can exercise little control (even if we wish to). For reasons I will spell out, we can be certain that the price and supplies of fossil fuels will suffer oscillations and disruptions in the period ahead that I am calling the Long Emergency.

The decline of fossil fuels is certain to ignite chronic strife between nations contesting the remaining supplies. These resource wars have already begun. There will be more of them. They are very likely to grind on and on for decades. They will only aggravate a situation that, in and of itself, could bring down civilizations. The extent of suffering in our country will certainly depend on how tenaciously we attempt to cling to obsolete habits, customs, and assumptions—for instance, how fiercely Americans decide to fight to maintain suburban lifestyles that simply cannot be rationalized any longer.

The public discussion of this issue has been amazingly lame in the face of America’s post-9/11 exposure to the new global realities. As of this writing, no one in the upper echelon of the federal government has even ventured to state that we face fossil fuel depletion by mid-century and severe market disruptions long before that. The subject is too fraught with scary implications for our collective national behavior, most particularly the not-incidental fact that our economy these days is hopelessly tied to the creation and servicing of suburban sprawl.

Within the context of this feeble public discussion over our energy future, some wildly differing positions stand out. One faction of so-called “cornucopians” asserts that humankind’s demonstrated technical ingenuity will overcome the facts of geology. (This would seem to be the default point of view of the majority of Americans, when they reflect on these issues at all.) Some cornucopians believe that oil is not fossilized, liquefied organic matter but rather a naturally occurring mineral substance that exists in endless abundance at the earth’s deep interior like the creamy nougat center of a bonbon. Most of the public simply can’t entertain the possibility that industrial civilization will not be rescued by technological innovation. The human saga has indeed been amazing. We have overcome tremendous obstacles. Our late-twentieth-century experience has been especially rich in technologic achievement (though the insidious diminishing returns are far less apparent). How could a nation that put men on the moon feel anything but a nearly godlike confidence in its ability to overcome difficulties?

The computer at which I am sitting would surely have been regarded as an astounding magical wonder by someone from an earlier period of American history, say Benjamin Franklin, who helped advance the early understanding of electricity. The sequence of discoveries and developments since 1780 that made computers possible is incredibly long and complex and includes concepts that we may take for granted, starting with 110-volt alternating house current that is always available. But what would Ben Franklin have made of video? Or software? Or broadband? Or plastic? By extension, one would have to admit the possibility that scientific marvels await in the future that would be difficult for people of our time to imagine. Humankind may indeed come up with some fantastic method for running civilization on seawater, or molecular organic nanomachines, or harnessing the dark matter of the universe. But I’d argue that such miracles may lie on the far shore of the Long Emergency, or may never happen at all. It is possible that the fossil fuel efflorescence was a one-shot deal for the human race.

A coherent, if extremely severe, view along these lines, and in opposition to the cornucopians, is embodied by the “die-off” crowd.1 They believe that the carrying capacity of the planet has already exceeded “overshoot” and that we have entered an apocalyptic age presaging the imminent extinction of the human race. They lend zero credence to the cornucopian belief in humankind’s godlike ingenuity at overcoming problems. They espouse an economics of net entropy. They view the end of oil as the end of everything. Their worldview is terminal and tragic.

The view I offer places me somewhere between these two camps, but probably a few degrees off center and closer to the die-off crowd. I believe that we face a dire and unprecedented period of difficulty in the twenty-first century, but that humankind will survive and continue further into the future—though not without taking some severe losses in the meantime, in population, in life expectancies, in standards of living, in the retention of knowledge and technology, and in decent behavior. I believe we will see a dramatic die-back, but not a die-off. It seems to me that the pattern of human existence involves long cycles of expansion and contraction, success and failure, light and darkness, brilliance and stupidity, and that it is grandiose to assert that our time is so special as to be the end of all cycles (though it would also be consistent with the narcissism of baby-boomer intellectuals to imagine ourselves to be so special). So I have to leave room for the possibility that we humans will manage to carry on, even if we must go through this dark passage to do it. We’ve been there before.

The Groaning Multitudes

It has been estimated that the world human population stood at about one billion around the early 1800s, which was roughly about when the industrial adventure began to gain traction.2 It has been inferred from this that a billion people is about the limit that the planet Earth can support when it is run on a nonindustrial basis. World population is now past six and a half billion, having more than doubled since my childhood in the 1950s. The mid-twentieth century was a time of rising anxiety over the “population explosion.” The marvelous technological victory over food shortages, including the “green revolution” in crop yields, accelerated that already robust leap in world population that had begun with modernity. Dramatic improvements in sanitation and medicine extended lives. Industry sopped up expanding populations and reassigned them from rural lands to work in the burgeoning cities. The perceived ability of the world to accommodate these newcomers and latecomers in a wholly new disposition of social and economic arrangements seemed be the final nail in the coffin of Thomas Robert Malthus, the much-abused author of the 1798 “An Essay on the Principle of Population as It Affects the Future Improvement of Society.”

Malthus (1766-1834), an English country clergyman educated at Cambridge, has been the whipping boy of idealists and techno-optimists for two hundred years. His famous essay proposed that human population, if unconstrained, would grow exponentially while food supplies grew only arithmetically, and that therefore population growth faced strict and inevitable natural limits. Most commentators, however, took the math at face value and overlooked the part about constraints. These “checks” on population come in the form of famine, pestilence, war, and “moral restraint,” i.e., the will to postpone marriage or forgo parenthood (from a perhaps antiquated notion that the ability to support a family might enter into anyone’s plans for forming one, or even that society could influence such choices). Malthus’s essay has been mostly misconstrued to mean that the human race was doomed at a certain arbitrary set point, and the pejorative “Malthusian” is attached to any idea that suggests that human ingenuity cannot make accommodation for more human beings to join the party on Spaceship Earth.

Interestingly, Malthus’s essay was aimed at the reigning Enlightenment idealists of his own youth, the period of the American and French Revolutions, in particular the seminal figures of William Godwin and the Marquis de Condorcet. Both held that mankind was infinitely improvable and that a golden age of social justice, political harmony, equality, abundance, brotherhood, happiness, and altruism loomed imminently. Although sympathetic to social improvement, Malthus deemed these claims untenable and thought it necessary to debunk them.

In recent times, population pessimists such as Paul Ehrlich, author of The Population Bomb (1968), Lester Brown of the Worldwatch Institute, and other commentators who predicted dire consequences of overpopulation by 1980, were supposedly shown up by the failure of dire events to occur; this led a new generation of idealists (including cornucopians such as economist Julian Simon) to proclaim that hypergrowth was a positive benefit to society because the enlarged pool of social capital and intellect would inevitably lead to fantastic new technological discoveries that would in turn permit the earth to support a greater number of humans—including social or medical innovations that would aid eventually in establishing a permanently stabilized optimum human population.

I would offer a different view. Malthus was certainly correct, but cheap oil has skewed the equation over the past hundred years while the human race has enjoyed an unprecedented orgy of nonrenewable condensed solar energy accumulated over eons of prehistory. The “green revolution” in boosting crop yields was minimally about scientific innovation in crop genetics and mostly about dumping massive amounts of fertilizers and pesticides made out of fossil fuels onto crops, as well as employing irrigation at a fantastic scale made possible by abundant oil and gas. The cheap oil age created an artificial bubble of plenitude for a period not much longer than a human lifetime, a hundred years. Within that comfortable bubble the idea took hold that only grouches, spoilsports, and godless maniacs considered population hypergrowth a problem, and that to even raise the issue was indecent. So, I hazard to assert that as oil ceases to be cheap and the world reserves arc toward depletion, we will indeed suddenly be left with an enormous surplus population—with apologies to both Charles Dickens and Jonathan Swift—that the ecology of the earth will not support. No political program of birth control will avail. The people are already here. The journey back to non-oil population homeostasis will not be pretty. We will discover the hard way that population hypergrowth was simply a side effect of the oil age. It was a condition, not a problem with a solution. That is what happened and we are stuck with it.

Trashed Planet

We are already experiencing huge cost externalities from population hypergrowth and profligate fossil fuel use in the form of environmental devastation. Of the earth’s estimated 10 million species, 300,000 have vanished in the past fifty years. Each year, 3,000 to 30,000 species become extinct, an all-time high for the last 65 million years. Within one hundred years, between one-third and two-thirds of all birds, animals, plants, and other species will be lost. Nearly 25 percent of the 4,630 known mammal species are now threatened with extinction, along with 34 percent of fish, 25 percent of amphibians, 20 percent of reptiles, and 11 percent of birds. Even more species are having population declines.3Environmental scientists speak of an “omega point” at which the vast interconnected networks of Earth’s ecologies are so weakened that human existence is no longer possible. This is a variant of the die-off theme that I consider unlikely, but it does raise grave questions about the ongoing project of civilization. How long might the Long Emergency last? A generation? Ten generations? A millennium? Ten millennia? Take your choice. Of course, after a while, an emergency becomes the norm and is no longer an emergency.

Global warming is no longer a theory being disputed by political interests, but an established scientific consensus.4 The possible effects range from events as drastic as a hydrothermal shutdown of the Gulf Stream—meaning a much colder Europe with much reduced agriculture—to desertification of major world crop-growing areas, to the invasion of temperate regions by diseases formerly limited to the tropics, to the loss of harbor cities all over the world. Whether the cause of global warming is human activity and “greenhouse emissions,” a result of naturally occurring cycles, or a combination of the two, this does not alter the fact that it is having swift and tremendous impacts on civilization and that its effects will contribute greatly to the Long Emergency.

Global warming projections by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) show a widespread increase in the risk of flooding for tens of millions of people due to increased storms and sea-level rise. Climate change is projected to aggravate water scarcity in many regions where it is already a problem. It will increase the number of people exposed to vector-borne disease (e.g., malaria and dengue fever) and waterborne disease (e.g., cholera). It will obviate the triumphs of the green revolution and bring on famines. It will prompt movements of populations fleeing devastated and depleted lands and provoke armed conflicts over places that are better endowed.

Global warming will add a layer of further desperation to the political turmoil ensuing from contests over dwindling oil supplies. It will aggravate the environmental destruction in China, where massive desertification and freshwater depletion are already at crisis levels, in a nation grossly overpopulated and attempting to industrialize just as the means for industrializing worldwide are diminishing. Global warming will contribute to conditions that will shut down the global economy.

Revenge of the Rain Forest and

Other Tiny Destroyers

The high tide of the cheap oil age also happened to be a moment in history when human ingenuity gained an upper hand against the age-old scourges of disease. We have enjoyed the great benefits of antibiotic medicine for roughly a half-century. Penicillin, sulfa drugs, and their descendants briefly gave mankind the notion that diseases caused by microorganisms could, and indeed would, be systematically vanquished. Or, at least, this was the popular view. Doctors and scientists knew better. The discoverer of penicillin, Alexander Fleming, himself warned that antibiotic misuse could result in resistant strains of bacteria.

The recognition is now growing that the victory over microbes was short-lived. They are back in force, including familiar old enemies such as tuberculosis and staphylococcus in new drug-resistant strains. Other old diseases are on the march into new territories, as a response to climate change brought on by global warming. In response to unprecedented habitat destruction by humans, and the invasion of wilderness, the earth itself seems to be sending forth new and much more lethal diseases, as though it had a kind of protective immune system with antibodylike agents aimed with remarkable precision at the source of the problem: Homo sapiens. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the precursor of AIDS, may be the revenge of the rain forest. In the twentieth century, a critical mass of humans encountered organisms long hidden in tropical backwaters, presenting ripe targets for opportunistic mutant strains of immunodeficiency virus jumping species. Once infected, these humans are able to travel out of the rain forest, courtesy of motor vehicles, and reenter the social mainstream with a newly acquired ability to infect others. One theory holds that HIV first developed in the 1940s from the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), which has long infected green monkeys, mangabeys, and baboons in Africa. The human immunodeficiency viruses HIV-2 and HIV-O both bear similarities to SIV. The virus may have jumped to humans through the consumption of monkeys as so-called “bush meat,” or through monkey bites. The virus may have infected human hosts, where it then mutated into its current lethal form. HIV probably first infected rural areas of Africa, slowly moving into the cities and around the world until it hit homosexual communities, where conditions were sufficient for rapid transmission of the disease via blood and, incidentally, other body fluids. AIDS also enjoyed the advantage of having a long incubation period...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- 1. Sleepwalking into The Future

- 2. Modernity and The Fossil Fuels Dilemma

- 3. Geopolitics and The Global Oil Peak

- 4. Beyond Oil: Why Alternative Fuels Won’t Rescue Us

- 5. Nature Bites Back: Climate Change, Epidemic Disease, Water Scarcity, Habitat Destruction, and The Dark Side of The Industrial Age

- 6. Running on Fumes: The Hallucinated Economy

- 7. Living in the Long Emergency

- Epilogue

- Afterword

- Footnote

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Long Emergency by James Howard Kunstler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Environment & Energy Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.