- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

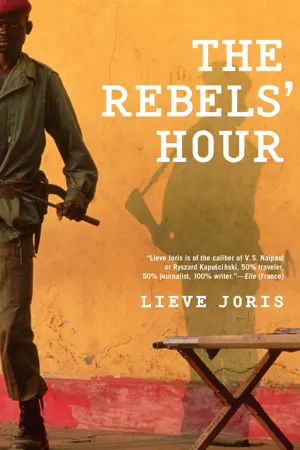

The Rebels' Hour

About this book

"A compelling, blood-soaked portrait of a young Tutsi rebel who rose to become one of the leading generals in the Congolese Army." —Details

Lieve Joris has long been considered "one of the best journalists in the world" and in The Rebels' Hour she illuminates the dark heart of contemporary Congo through the prism of one lonely, complicated man—a rebel leader named Assani who becomes a high-ranking general in the Congolese army. As we navigate the chaos of his lawless country alongside him, the pathologically evasive Assani stands out in relief as a man who is both monstrous and sympathetic, perpetrator and victim ( Libération, France).

"Lieve Joris is of the caliber of Naipaul or Ryszard Kapuscinski, 50% traveler, 50% journalist, 100% writer." — Elle (France)

Lieve Joris has long been considered "one of the best journalists in the world" and in The Rebels' Hour she illuminates the dark heart of contemporary Congo through the prism of one lonely, complicated man—a rebel leader named Assani who becomes a high-ranking general in the Congolese army. As we navigate the chaos of his lawless country alongside him, the pathologically evasive Assani stands out in relief as a man who is both monstrous and sympathetic, perpetrator and victim ( Libération, France).

"Lieve Joris is of the caliber of Naipaul or Ryszard Kapuscinski, 50% traveler, 50% journalist, 100% writer." — Elle (France)

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

KINSHASA

2003

Assani felt naked as a baby on his arrival in Kinshasa. For years he’d been driving around in the east in a pickup with eight soldiers, armed to the teeth. Now he stepped off the plane with just a few bodyguards. The sky above the city was milky white. He’d forgotten how hot it could get here—the tropical heat fell like a clammy blanket and he was struck by the sickly reek of palm oil and putrefaction. The asphalt gave slightly under his army boots.

Sirens blaring, the convoy drove the miles-long boulevard to the city center. The overpopulated cités* with their labyrinths of narrow sandy streets were hidden behind garish billboards for Vodacom and Celtel telecom services. Minibuses shot past, so full that legs dangled from the half-open back doors and children hung their heads out of the small windows, gasping for air. One bus stopped to pick up a maman* carrying a basket of baguettes; the passengers somehow made room for her.

Then suddenly he was in the Grand Hotel, formerly the Hotel Intercontinental, his bodyguards warily investigating the corridors while he inspected his room. Through the window he could see the Congo River, water hyacinths bobbing toward the rapids, and the skyline of Brazzaville in the misty distance. He’d recently learned to swim. In the high plains in the east of the country where he’d grown up the rivers ran fast and cold and he was always horribly sick if he had to travel by boat, but now he’d overcome his aversion to water. No more traipsing along a riverbank trying to devise a way across.

That afternoon he was driven out to Camp Tshatshi to meet the others. Some had phoned him while he was still in Goma. He had no idea how they’d gotten hold of his number, but as soon as his nomination was announced the calls started coming. People complained about their superiors, saying they couldn’t wait for him to arrive. That subservient, singsong tone—he couldn’t stand flattery, and nothing they said made the slightest impression on him.

The guards at Camp Tshatshi peered in through the car window as if he were a revenant, a ghost. The camp was in a euphoric mood. His arrival had been postponed so many times that no one really believed he’d ever turn up. He recognized some of the soldiers who flocked to greet him, men he’d last seen here five years ago when he fled the city. They were thrilled and wanted to know everything: How had he gotten away? How had he survived those first few months? This from people who would gladly have lynched him at the time.

As soon as he managed to get himself a car, he drove into town with his kadogos*—little ones—cautiously, the way he was used to moving about, on the alert for an ambush. The signs of authority he’d been expecting weren’t much in evidence. The situation felt fragile; no one could guarantee anyone else’s security.

He and his bodyguards wore Burundian uniforms and big slouch hats. In the past they’d have been conspicuous dressed like that, but to his surprise the Kinois* paid little attention. It seemed they had other things to worry about. It was only when he stopped at a sidewalk café in the cité for a drink that a few inquisitive people came up to them. The soldiers from the east were mibali, real men, they said. They’d been told the soldiers were all dead, but here they were, alive and well! It was a good thing they’d come. Maybe they should take over again; those who’d stayed behind hadn’t achieved very much.

Driving back, he got lost. He didn’t know Kinshasa very well. He needed a map, but how could he get one? Surely it would look suspicious if a man with his history asked for one now.

He was incorporated into the reunited national army, along with other high-ranking officers. Everybody was there, and he saw Joseph Kabila again. When Joseph’s father was alive they’d been young soldiers together, and even after the war broke out they’d occasionally phoned one another, but they hadn’t spoken since Mzee Kabila died and Joseph stepped into his shoes. Assani had his number, but you needed to keep statesmen at arm’s length; you never knew who else they might still be talking to.

The thirty-two-year-old president had bags under his eyes—presumably the presence of all those rebels in town made it hard to sleep at night. His father’s friends must have told him they’d come here to kill him and that Mzee Kabila would turn over in his grave if he knew his son had made peace with his sworn enemies. Representatives of the international community who’d dragged the young president through the peace negotiations, from one compromise to the next, looked down from the podium with satisfaction. They’d saddled him with no fewer than four vice presidents.

Assani was taller than the rest, and he slumped down in his seat so the cameras wouldn’t pick him out. From under his new general’s cap, too big for his narrow head, he could look around surreptitiously. The transitional government was an amalgam of stones, roots, and cabbage—how could you ever make decent soup out of that? Long after the vegetables were cooked, the stone would still be a stone.

There was Yerodia. As soon as he was appointed vice president he’d rushed off to Mzee’s mausoleum with a television crew, to invoke his help and to have a good cry for the cameras. He had the dazed look of an inveterate cigar smoker and he’d dressed for the occasion by tucking a silk handkerchief into the breast pocket of his sleeveless jacket.

Next to this tropical dandy, Vice President Ruberwa looked sober in his gray suit. Like Assani, he was a son of the high plains. It couldn’t be easy for him to sit so close to Yerodia, who’d said at the start of the war that Ruberwa’s people were vermin to be eradicated—if only because some of those people would see them together on television this evening and call him a traitor.

As the long, pompous speeches dragged on, the officers caught each other’s eye, whispered, and laughed, like schoolboys forced to sit still for too long. Afterward they had their pictures taken. Another freshly appointed general, a member of the Mai Mai, clearly felt intimidated by the bustle of the city. He pulled Assani aside conspiratorially, spoke to him in their own dialect, and suggested the officers from the east should be photographed together. “Not with the others,” he whispered. “Just us.” To think they’d been archenemies over there.

It was the end of one era and the beginning of the next. No more crouching in trenches while Antonovs shat bombs and the sky lit up, like in an American war movie. No more killing, destruction, shooting at everything that moved—he felt no particular sensation.

At Camp Tshatshi, his new workplace, little had changed. A vague smell of urine hung around the corridors of the main building, rusty springs stuck out of the leather couches by the stairs, ceiling tiles were hanging loose, and some of the windows were broken as ever. They hadn’t even repaired the locks on the weapons depot, which he’d forced before fleeing five years before. How could they have dreamed of winning a war from such a dilapidated HQ?

Responsible for the budget of the armed forces—it had sounded important enough, but the office he was shown to by his predecessor was empty. No table, no cupboard, no chair, and in this oppressive heat not even an air conditioner, only a hole in the wall where it used to be. When they toppled Mobutu in 1997 there had been paperwork, archives, but now there was nothing. How had Kabila’s men worked, for God’s sake—by walkie-talkie?

His predecessor was a surly man, not the type you could ask questions. He handed Assani a cell phone from the insolvent company Telecel and got him to sign for it. That was all: one phone, without a battery—when he tried for a replacement he found none was available anywhere in the city.

While he was on the way back to the hotel his wife called, as she had so often in recent days, probably to check he was still alive. When they met he was head of military operations in Goma, the rebel capital. She’d thought they made the perfect match; nothing had prepared her for the situation he now found himself in, nearly 1,000 miles from home, in enemy territory. She was much younger and the panic in her voice was starting to irritate him. “Leave me alone, won’t you,” he said. “Why keep calling? You people can’t imagine how complicated everything is over here.”

In his hotel room he turned on the television halfway through the program Forum des Médias. The participants were fulminating against the rebels from the east, saying they’d come to kill the president, that he’d come to kill the president. He sat rigid on the bed. So the people who wanted him dead were still around. They had a free hand here.

Politicians from the east, desperate to secure jobs in government—why had he followed them? Why return to a city where he’d escaped death by a whisker? What was he doing here, in this room, this hotel? He didn’t like hotels. He was allergic to the wall-to-wall carpeting and the air-conditioning was making his nose clog up. He didn’t feel safe in this environment of strangers and diffuse noises.

That night he was up in the high plains, walking down a narrow mountain track toward the city. The great river far below churned and thundered more and more violently, until the wash slopped over both sides of the path. A fine mist soaked his face and the current sucked his feet out from under him.

He jolted awake, groped for his wife’s warm body, realized where he was, and struggled to suppress the fear that was mounting in him again. The violence was cyclical; he’d never known anything else. It had always been wartime.

HIGH PLAINS

1967

The people of the high plains in the east lived outside time; they rarely had any idea how old they were. But his mother remembered exactly when he was born: on the second day of the second month of the year 1967, early in the morning, just before the chickens started to talk. It was a blessed day, since up to then she’d had four daughters, and a woman without sons was regarded as childless by her in-laws. His birth safeguarded her late husband’s cows, which would otherwise have been shared out among his uncles. She named him Mvuyekure, he who comes from afar, after his grandfather, who had also been a long time coming. Everyone called him Zikiya.

They lived in Ngandja, a hilly region of unspoiled green meadows. Zikiya’s great-uncle Rumenge, who once killed a lion with his spear, had moved there around 1955 with his two wives and children. He encountered a small community of Bembe, who grew cassava and beans and hunted monkeys and wild swine in the surrounding forests. As soon as he’d befriended their chief the others joined him. Before long there were a hundred of them.

They were known as Banyarwanda*—people of Rwanda—since that was where they came from originally, although some had arrived from Burundi. This was in the days before the Ababirigi, as they called the Belgians, when there were no borders and their ancestors habitually moved westward in search of better grazing for their cattle or after conflicts with local rulers.

Zikiya was about four when rumors of rebels came blowing through the hills like an evil wind. The rebels were after their cows, which they’d promised to share out among the poor Bembe farmers; they soon won over the Bembe chief, and the first fatalities followed.

The Banyarwanda gathered their meager possessions and fled—men, women, children, cows, and sheep—escorted by armed warriors who’d left the safety of Minembwe to come and rescue them. That flight and his father’s death somehow became intertwined in Zikiya’s childhood memories, and he grew up with the bitter conviction that his father had been killed by Bembe rebels.

His uncles said he’d made the trip on his mother’s back, but the way he remembered it he must have been able to walk, because during a rest break he wandered away from the path. His mother didn’t notice until the caravan was about to move on. In a panic, she went looking for him and found him playing happily in a banana plantation. It was the first time he’d ever seen her cry.

They traveled for seven days. One moment they were walking across an open landscape of rolling meadows, the next through the forest, struggling uphill between trees with long frayed beards of lichen and fast-running streams full of slippery green boulders. Occasionally they were attacked. By the end of the journey ten people were missing, and several cows had run off during clashes with rebels.

In Minembwe they saw army trucks patrolling the hills. President Mobutu had come to power six years before, in 1965, but he had great difficulty establishing his authority in this eastern outpost. The high plains suited the rebels perfectly: they were sparsely populated, with hardly any roads, and Burundi, Rwanda, and Tanzania were close by.

The Cold War was still at its height. To the partisans of rebel leader Laurent-Désiré Kabila, Mobutu was a puppet of the Americans and the former colonial rulers. From socialist Tanzania the rebels moved into the mountains to fight his regime. They called themselves Simbas, Lions. At first the Banyarwanda tried to stay on good terms with the Simbas, but when they realized the rebels were after their cattle they turned to the government army for protection. You could kill a man, but not his cow.

In those days Mobutu’s soldiers were still acting correctly. They kept a low profile and listened to the people. They supplied the Banyarwanda with weapons to defend their cattle, and if they needed a cow for food they paid for it.

A lieutenant colonel visited them at their new abode in Minembwe. Zikiya’s mother gave him some milk. “Watch it, they’re about to run away,” the officer told the soldiers standing near the door. That was what usually happened when soldiers came to a village: first they were offered milk, then people took to their heels.

The colonel had used a Lingala* word that Zikiya understood to mean “move house.” “Why are they going to move house?” he asked. The man laughed, pulled him close, and shared his milk with him. Zikiya didn’t want to leave his side, and his mother, far from running off, came over to hear what he had to say. “That was a good soldier,” she said afterward.

Later his family returned to Irango, where they’d lived before moving to Ngandja. Irango lay hidden behind a ridge and no one passing through would ever suspect that people were living there. The round huts—bamboo frames covered with dried cow dung and thatched with straw—were a sorry sight after standing empty for so many years, but they quickly built new ones. Now they could doze off in the evenings again to the heavy breathing of cows asleep in the grass.

Cows were sacred. Zikiya’s people drank cow urine as medicine and used it to rinse out their ngongoros, wooden milk bottles with woven lids. A cow doesn’t talk, they said, so you can’t argue with her; like an angel, she won’t hurt a soul. They seldom ate meat but lived on milk, maize, and beans. They had the same tall, slender build as cattlemen in other parts of Africa. If a cow died they mourned, whereas the Bembe, who were short and muscular, rejoiced in the knowledge that they’d be eating meat very soon.

Zikiya’s father had been the eldest son in his family. When his grandfather died, Zikiya was given a bull and decked out in the old man’s personal possessions: a white pagne*—length of fabric—that knotted at the shoulder and was far too big for him; an ivory bracelet; and an inkwebo, the long iron-tipped walking stick the men always carried as they strode through the hills—you could use it to prod the buttocks of a reluctant cow or chase away nosy children, or plunge it into a stream to vault across. He hadn’t held on to any of these heirlooms, but he would never forget the ceremony.

He and his older sister were both late arrivals, born when their siblings had already left home. “Don’t bother about her,” his mother said of his sister. “We’ll marry her off when the time comes.” Sons increase your own family, the saying went; daughters increase someone else’s. Occasionally his mother sold a cow so she could buy things he needed for school, but she always consulted him first about which cow to sell. If she’d picked one that responded when called, or that went ahead leading the way, she’d choose one of the others instead.

Before leaving for school in the mornings he had to take the cows to pasture outside the village. By the time he got back, white clouds would be rising from the dewy straw roofs, the whole of Irango steaming gently in the strengthening sun. Inside, smoke from the wood fire hung low in the room. It stung your eyes if you weren’t used to it; he’d noticed when strangers visited how their eyes always...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Map

- Contents

- Preface

- The Rebels’ Hour

- Historical Background

- Chronology

- Historical Characters

- Glossary

- Footnote

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Rebels' Hour by Lieve Joris, Liz Waters in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.