- 174 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

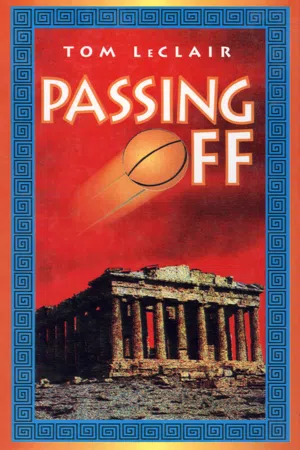

Passing Off

About this book

Michael Keever, former Celtic teammate of Larry Bird's, changes his name and passes himself off as Greek-American to play in the Greek Basketball Association. When Michael appears on Greek TV in a public service spot against pollution, a viewer suspects that his ethnic background would not qualify him to play in Greece.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Two weeks after I signed with Drinkman we were in the Athens airport with a sellout crowd of high-season tourists. After waiting an hour for our luggage and another forty-five minutes to pass through customs, we funneled into a line moving toward the lobby. Through the doors I could see bodies packed five and six deep against a railing. The Greeks were jumping, waving, shouting, crying. At the single gap in the railing, two policemen were trying to maintain a passage through the crowd, but people were pressing in from both sides, closing the gap just outside the railing. Out of the crowd, a short old man with thick arms and then an even shorter, heavy-hipped woman pushed past the policemen as if they were porters, scurried to incoming passengers, and clasped them in their tracks, stopping the line. Children ducked under the railing, darted forward, and jumped on arrivals. Passengers in front of us abandoned their carts and charged to the railing, where they embraced people who came pushing and shoving to the front. A man behind us rushed past us to the railing where he was beaten on the shoulders and then kissed on both cheeks by three middle-aged men who looked Middle Eastern. He pummeled them and kissed them back. The Greeks acted like fans welcoming home NBA champions.

Pushing a luggage cart with our six suitcases, I had enough weight to open a hole in the crowd at the rail and squeeze out into the lobby where I was tall enough to see young women holding up signs to welcome their groups. “Hotel Porto Rafti.” “Hilton.” “Aegean Cruise.” I looked around for the Panathinaikos representative who was supposed to meet us. When I spotted a guy holding up “Key Tours,” I said to myself, this team has some style: Key takes his high-li show on the road. I pushed over to the man and introduced myself. He shook hands and then looked at the clipboard he was carrying.

“Do you have a voucher?” he asked.

“Exile,” I thought, Drinkman’s term for Third World leagues. Drink has sent me to a team that makes me prove I’m me to get a ride into the city. I asked the guy if this was how all Greek teams treated their players.

“I’m sorry, sir. I do not understand. Do you not wish to take one of our tours? We offer day tours of Athens and longer trips to all important sites. Key Tours unlocks the secrets of ancient Greece.”

That was turnover number one. Eventually, the tallest man with six suitcases, wife, and five-year-old daughter was spotted by a short woman with a sign that was a secret to me: KYBEPNOS, my new name in Greek letters.

Greece, we discovered right away, is not Italy, the leisure league you may have read about, that Danny Ferryland where big name players find a villa, car, and servant waiting for them. Furnished apartments were rented before we could see them, sometimes before we could call to see them. To find a place to live, we had to walk the streets looking for little “Enikiazete” signs next to doorbells. Our driver had suggested Kolonaki, which Ann’s guidebook described as “an older section on the slopes of Mt. Likavitos. Resembling New York’s Upper East Side, Kolonaki is dotted with embassies and chic shops and is home to a large foreign community.” After five days, one basement apartment, and one flat available in a month, we rang a bell, heard English spoken back, and were shown into a fifth-floor apartment. Across the twelve-by-twelve living room were glass doors. Framed by the doors, as if it were a giant painting, was the Parthenon. We walked out onto the balcony, looked at half the city below, and Ann said, “We’ll take it.”

“What if it doesn’t have a kitchen?”

“We’ll cook out here.”

“Or bedrooms?”

“We’ll buy a tent.”

We signed a lease and gave the landlady three months rent, but Ann refused to leave the apartment until I’d brought in our suitcases. Located between our hotel in the Plaka tourist district and Panathinaikos stadium, our new home did have a half kitchen, one bedroom, and a black-and-white TV. We didn’t care because Kolonaki had everything we needed, we could walk almost anywhere else we wanted to go, and we were spending most of our time outdoors.

Like property, people in Athens move faster than in the States. The avenues converging in the city center are like four-lane drag strips, cars lurching away from lights, streaming through yellow, squealing into the crosswalk on red. Buses and trolleys have racing stripes. Midday looks and sounds like rush hour: streets jammed with cars, drivers honking and screaming, passengers waving out their windows. To speed through their overcrowded streets, Greeks are jockeys. Little sixty-year-old men, ties flapping in the wind, whip between lanes of stalled traffic on dirt bikes. Women ride sidesaddle behind their husbands or tuck their knees tight together on Vespas. Teenagers throttle minibikes as if they’re trying to get donkeys to run. The real jocks, though, are the short young men hunched over huge Hondas and Suzukis, whispering to their handlebars.

In the Plaka, tourists walk slowly, rubbernecking, taking it all in, wary of being cheated, fearful of pickpockets. The morning crowds on the sidewalks in the rest of Athens are young men running goods into shops from double-parked vans, women with plastic bags bustling through the day’s shopping, older men and boys hustling trays with small cups of coffee and large glasses of water to office workers, the workers themselves out on the sidewalks for something to eat on the go. Ten in the morning in Syntagma Square is like noon in Memphis, when people descend from their towers and scamper to lunch. The Greeks are darker, the men more casually dressed, the women classier, no pantssuits, and they all move closer to you than southerners, brushing shoulders or hips, steering through oncoming walkers with a slightly outstretched arm, placing a light hand on your elbow as they pass. They walk touching each other, turned toward each other, not seeming to look where they’re going, because they’re trying to be heard above the street noise. Like players pumping up teammates, Greeks holler in each other’s faces, their mouths forming the words against the noise. The speech is noise, adding to the other noise, crowd noise in this densely crowded city.

“No savage quickness,” Drink said about the natives, but they’re fast even when sitting down. The first day Sara, Ann, and I sat in a cafe, she asked me why my eyes were flicking and fingers were twitching. I hadn’t noticed. I was responding to the jerking heads and darting hands at the tables all around me. A guy off to my left was raising his eyebrows like the Lightning center signaling for an alley-oop. My hand wanted to float my beer bottle up over the back of his companion’s head. The Greeks’ constant gestures remind me of rappers’ hand movements and finger codes, secret signs for the home-boys. Like young blacks in the States, Greeks are always shaking hands, bobbing and moving when they’re standing still. Their motion keeps your eyes sharp, your body ready to move. Even sitting down, I felt like I was on the floor.

My only problem was finding something to tape. While Ann was telling Sara stories about Athena the woman warrior, I shot the Parthenon but it didn’t move. Although the figures in the museums were buffed, they were all white and posed. The statues of Athena and Apollo in front of the university were high in the air but pedestaled. We didn’t see any of the Greek fishermen that danced on the travel tape I’d rented, Anthony Quinn Greeks. No crazy customs like Muslims bowing to Mecca, just this density of people in public space. The differences here are difficult to film. The light bouncing off the surrounding stucco and onto my balcony is like the high-intensity floods above the court, but you can’t shoot into the light. The sun pleases my eyes, sneaks through cracks in the shutters in the morning, gets me up, somehow gives me appetite. Like the people, the food is dense. There are no air holes in feta. Olives come with pits. We were sniffing the pots in a taverna one night when we caught a smell we couldn’t identify. The waiter tapped his head. “Brains, we cook brains.” The Greeks are eating brains. There’s a difference. I’ll need a steady diet to learn the language. The signs on stores are alien squiggles, patterns I can’t recognize, can’t even sound out. We roam the streets, look in the windows, go in the shops, handle the products, touch the textures. Cotton or polyester? Wood or plastic? Feel the goods, rap the watermelon. One day Ann rapped and hesitated. The old guy with two teeth took it out of her hands and split it with a foot-long knife. It was tomato red. She just couldn’t hear the color. At the supermarket I saw a woman smelling a can of coffee. Honey is identified by different habitats. Greeks can taste where bees live. How would I get that on tape?

I feel a subtle pressure. The air and light seem to surround me, things and people are closer together. It’s a difference you have to sense. I feel I have my proprioception here. Ann said it’s the only word I know as long as motherfucker. Ran across it in a phys. ed. class. It’s the sixth sense, connecting the others, controlling balance, the key to every athlete’s body. After our walks, when Sara and Greeks are taking their midday nap, Ann and I quietly balance our long-legged bodies on our six-foot bed and secretly take our second honeymoon, more moving density I can’t tape. “Do you think there’s something in the water here?” Ann asked. “It’s everything,” I teased her, “all the senses in play are good for the pro.”

Even the language is dense. I sent Coach Cater a postcard of Greek script from ancient times, when words weren’t separated. The writing looked like nonsense, the work of a child with alphabet blocks and a chisel. The language is still compressed, consonants impossibly rubbing up against each other. “M” and “P” together at the end of a word are useful: jump, pump, dump. But what are your tongue and lips going to do with those letters at the beginning of a word if your parents never spoke Greek? No other country uses this alphabet, speaks this language. I doubt I ever will. I don’t speak that much English, a smattering of Afro-American. Ann is trying to learn Greek, but maybe I don’t want to. Texture would become a text, motion X’s and O’s. The proprioception would be different then. Reading and listening could overwhelm the rest. I’d lose my touch. Food wouldn’t taste the same. I wouldn’t be able to smell Greeks passing me in the street. I take in a few words that seem like presents from Greek, signs of our connection, welcoming sounds. Running around looking for a place to live, jumping away from cars, lugging groceries home on foot, heaving our rugs over the balcony railing to air, I thought Greeks are like pentathletes. When I learned to count to five, I realized that “athlete” is Greek.

For Greek and American athletes, Coach Zikopoulos’ one-eyed demand was suicidal conditioning. “To running faster and longer over other teams,” he explained, “we must overtraining.” Even before Coach Z introduced Henderson and me to the team, he made us all run the suicides. They are the secret all basketball players keep. No other sport does the suicides. If you haven’t played basketball, you haven’t seen them. They’re not run before a game. They’re not usually run before a practice. After practice, hangers-on or reporters don’t stick around because the suicides are an inside story no one wants to watch or tape. Ten men, all stripped to skins now, line up along one baseline. The coach blows his whistle and the men, no longer players, sprint eyes down to the foul line, touch the floor with one hand, and sprint back to the starting line, sprint eyes to the floor to midcourt, touch down, and sprint back, sprint without looking to the far foul line, touch, and back, sprint blindly the whole floor, touch the other endline, and sprint back. The men rest, the coach blows the whistle, and they run. Rest, whistle, run, over and over, up and down, around and around. The men turn into bodies, large sweating bodies. They go out strong, an even line together on the first circle. Then the group starts to break up. They begin passing each other going to midcourt and on the third circle out the floor is crowded with bodies going in opposite directions, the big bodies sometimes colliding with the smaller bodies already coming back. On the last circle the bodies are strung out all over the floor, stabbing at the line, slipping in the pools of sweat, heads swinging, arms flailing, legs staggering on the long stretch home.

It is suicide not to run hard and suicide to run hard. If you finish last, you may run while the others are resting. If the coach catches someone dogging, the whole team will run extra suicides. If you go all out and finish in front, you feel you’re going to die on the baseline. You stand doubled over, your lungs looking for air on the floor, or you throw your head back, chest heaving, gulping for any oxygen your teammates may have missed. You wish your nose was the size of your mouth. You wonder why you’re here, why your ancestors came up out of the sea and became mammals. The air you get comes with the stench of sweat and garlic coming out of the Greeks’ pores. In the September heat, sweat is pouring out so fast you’re over-cooling, shivering in your own overheating. The sweat collects in your ears, burns your eyes, tackles into your mouth, puddles like sea water on the floor. Your lungs feel clenched in your chest. Your heart pounds in your head. You pray that it’s the only sound you’ll hear, that the whistle won’t blow, that the coach will swallow his whistle, that the motherfucker will strangle at the other baseline, gasping like you, sweat coming out of his eyes. The whistle blows. Sprint, bend, sprint. Your stomach aches, your back aches, your arms and legs ache. You wish for a cramp, a painful knotted muscle, a reason to stop that the trainer can feel, hard evidence. You even consider colliding with another body, risking injury to one limb to stop the pain all over.

The suicides are called that because they’re the absolute negative and because they go on and on. Running the suicides, you may be stretching tendons, increasing muscle density, expanding lungs, building endurance, preparing to run the fast break, but what the suicides are really doing is subtracting, little by little by little, taking off weight, shedding differences, cancelling pride, decreasing mind, diminishing instinct, forgetting the body’s good sense. In the suicides, perceptions don’t matter. No skills are involved, no teamwork. You’re running for yourself, against yourself. No statistics, only the coach’s count. No language, just the whistle. No place to hide, no crowd to keep you going. From the suicides there’s no escape, no leaving early, because they’re what you’ve chosen in order to play, to work, to be here, to be anywhere basketball is played for pay. Coach Z blows his whistle and you run and you make yourself run and force yourself to keep running harder and harder, slower and slower until there is no more air, no more water, no more energy inside. Then you crumple and vomit. I was the first. Nothing came up. I was on my hands and knees retching, turning inside out, but nothing was inside. The other bodies kept running. It was two more whistle blows before Henderson went down on his knees and splattered green bile on the floor. I lay on the sideline, a towel filled with ice under the back of my neck. I sucked an ice cube and wondered if twenty-eight was too old for the Greek Basketball Association. I’d been keeping in shape in the States. The big guys are supposed to go down first.

The trainer flapped a towel over my white, clammy body. He was my best friend in this country, the man with the ice.

“Zesti,” he said.

I sucked the cube.

“Hot,” he translated.

Zesty, I realized.

“Also the Nefos is bad today.”

“Nefos? What’s the Nefos?”

“The cloud, the pollution,” he said, pointing up toward the open windows. “Outside.”

So that’s why the Greeks are still running. They’re used to the weather inside the gym. That yellow cloud I see behind the Acropolis every afternoon is the Greeks’ home court advantage in the Athens basin, this LA without the Lakers. I had run the suicides in full sweats in Vermont, in 90 percent humidity in Memphis, and under the master of loathing in Rockford. It might take a few days, but I’d catch the Greeks in the suicides.

Ahead in conditioning, the Greeks were far behind in teamwork. “Fazbreaking, fazbreaking,” Z yelled in English, z-ing the two words together for speed. Panathinaikos ran up and down, but it wasn’t fast and it wasn’t the break. “Broke,” I heard Henderson mutter, “GRs’ game broke.” All of the Greeks were shooters—the fill-in point guard, the power forward, two kids about nineteen up from the junior team, and the substitute center. Petros was six-five and 280 pounds. The club found him working in a marble quarry when he was twenty-five. Petros had hands of stone and only one thumb. That didn’t stop him from airing out fifteen-foot tiptoe “jumpers.” Those first sessions, the Greeks would not give me the ball. Forwards rebounded, dribbled the length of the floor, and threw up fall-away baseline jumpers. If a guard got a long rebound or a steal, he’d run down and fire a three before his teammates could get into better position and he’d have to pass.

Only Henderson and Koko, the thirty-five-year-old starting center, didn’t get their share of shots. Koko was from another generation, he said, when parents waited to see if a boy was tall before putting a ball in his hands. If Koko grabbed a rebound, one of the Greeks who could dribble would run to him and take the rock off Koko’s hands. It would be up in the air before Koko could get down the court. Henderson concentrated on offensive rebounding. Watching the ball on its way to the rim, he figured the angles, calculated the bounce, carved his space, levered with his hips, pried with his elbows, pushed off with his hands, and then exploded up above the Greeks. The third day of practice Henderson cracked Koko’s nose. “That motherfucker’s too slow to live,” Henderson said. Like most brothers, he must have grown up playing thirty-three in the schoolyard, the ghetto game you don’t see on TV. Five or ten black kids around one hoop. It’s all against all, one on four, one on seven, one on whoever is out there. You have to get the ball yourself and you have to shoot it yourself. There is no one to pass to. No fouls are called. Make it, take it. Keep it, reap it. Miss it, kiss it.

Two of the forwards were named Papadopoulos. The one with touch I called “Pop.” He reminded me of Chris Mullin, a six-six lefty, a little slow afoot but a quick release and nice rotation, a soft ball. He could drop it from the wing and baseline. Pop was a country boy whose English was limited to basketball terms used in Greek: “tzuball,” “bloke out,” “passa.” Pop never tied up anybody for a jump, rarely blocked out, and always shot. Defense, rebounding, and passing were foreign to him. I wondered if it was because Greeks didn’t have words for them. The power forward was “Dop.” He explained to me in excellent, British-accented English why he should get at least twelve shots a game. Give him time to set up and he could hit the three, but he had no feel from fifteen feet in. “Face-shy,” guards call a player like Dop, afraid of getting his shot slapped back in close. He had good shoulders and a quick rise for six-eight. His hips and heart were too small to help Koko and Henderson much in the paint.

Kappa had played some point with another team. He said he was happy to have me here. Now he could shoot it out with Calphoglou for the number two slot. They were like stubby bookends, both six-one and thick. Kappa went to the rack, Lou buried the threes. Kappa could take his man off the dribble, Lou moved better without the ball. Kappa learned his English in tourist cafes, Lou had an American wife.

Coach Z wanted us forcing the break every possession and, if we didn’t score, he had us running a motion offense. The “Panatholes,” as Henderson called the Greeks, weren’t moving without the ball. They were making me into a “bouncer,” Drink’s term for a point guard who pointlessly dribbles the ball waiting for something to happen. To get the most out of my shooters, make a team go, I need to handle the ball every transition, receive the outlet, push the pace, decide who finishes. If we don’t break down the transition defense, I call the set, choose the option, distribute the rock, open up for the release pass if the play doesn’t work, and when the shot clock goes under seven I make something happen. I’m the funnel point in the egg timer, twenty-four seconds in the NBA, thirty here. The ball comes to me from the ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Prologue

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Epilogue

- Copyright Page

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Passing Off by Tom LeClaire in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.