- 608 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

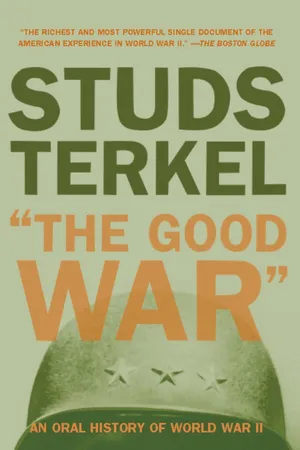

Winner of the Pulitzer Prize: “The richest and most powerful single document of the American experience in World War II” (The Boston Globe).

“The Good War” is a testament not only to the experience of war but to the extraordinary skill of Studs Terkel as an interviewer and oral historian. From a pipe fitter’s apprentice at Pearl Harbor to a crew member of the flight that dropped the atomic bomb on Nagasaki, his subjects are open and unrelenting in their analyses of themselves and their experiences, producing what People magazine has called “a splendid epic history” of WWII. With this volume Terkel expanded his scope to the global and the historical, and the result is a masterpiece of oral history.

“Tremendously compelling, somehow dramatic and intimate at the same time, as if one has stumbled on private accounts in letters locked in attic trunks . . . In terms of plain human interest, Mr. Terkel may well have put together the most vivid collection of World War II sketches ever gathered between covers.” —The New York Times Book Review

“I promise you will remember your war years, if you were alive then, with extraordinary vividness as you go through Studs Terkel’s book. Or, if you are too young to remember, this is the best place to get a sense of what people were feeling.” —Chicago Tribune

“A powerful book, repeatedly moving and profoundly disturbing.” —People

“The Good War” is a testament not only to the experience of war but to the extraordinary skill of Studs Terkel as an interviewer and oral historian. From a pipe fitter’s apprentice at Pearl Harbor to a crew member of the flight that dropped the atomic bomb on Nagasaki, his subjects are open and unrelenting in their analyses of themselves and their experiences, producing what People magazine has called “a splendid epic history” of WWII. With this volume Terkel expanded his scope to the global and the historical, and the result is a masterpiece of oral history.

“Tremendously compelling, somehow dramatic and intimate at the same time, as if one has stumbled on private accounts in letters locked in attic trunks . . . In terms of plain human interest, Mr. Terkel may well have put together the most vivid collection of World War II sketches ever gathered between covers.” —The New York Times Book Review

“I promise you will remember your war years, if you were alive then, with extraordinary vividness as you go through Studs Terkel’s book. Or, if you are too young to remember, this is the best place to get a sense of what people were feeling.” —Chicago Tribune

“A powerful book, repeatedly moving and profoundly disturbing.” —People

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access "The Good War" by Studs Terkel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

BOOK FOUR

dp n="402" folio="386" ?dp n="403" folio="387" ? CRIME AND PUNISHMENT

ALVIN (TOMMY) BRIDGES

Bay City, Michigan, is one of the Tri-Cities, the other two being Saginaw and Midland. It is an industrial area, hard-hit by the recession.

He had been a Bay City policeman for thirty-one years; during his last four years on the force, he was police chief. He retired in 1968.

It was a useless war, as every war is.

I got into more trouble when I was in the army in saying so. They give us this I-E, information and education. Every time they’d get one of these shavetails up there, just come outa college, sellin’ us the idea that this war was essential. There was a whole company o’ men there, officers too. I blew up and said, “Is any war essential?” I’m not an antiwar guy, I’d go tomorrow if there were a war. But this world’s not gonna last long unless we stop it, this nuclear business.

I joined the army on February 20, 1942. To get somethin’ to eat. (Laughs.) I don’t know how the war was ever won, because they had no rhyme or reason why they selected a guy for an MP. When I was at Fort Custer, they was three guys ahead of me went in the air force like that, two of ’em in the infantry, and they come to me and said, “You’re MP.” The training they give us was just like a new sheriff goin’ in and gettin’ a new bunch of deputies, trial and error. It had nothin’ to do with police business.

When we got our first assignment in London, I don’t know how we ever made it. (Laughs.) The officers, they were dumber than we were. When I went to Paris, the first guy they sent out was me. They figured I knew all about Paris. I didn’t know a hill o’ beans about it. (Laughs.)

London, we got there New Year’s morning of ’43. Stayed till just six weeks after the invasion. When we got to Paris, there’s still occupying troops. We were just like a new police department for the GIs.

We had a great amount of trouble with supplies being sold. People were starving to death over there and they would sell truckloads, big trucks, they’d be loaded with anything, didn’t matter what it was. They’d sell it. The Frenchmen had all that money right there and they’d buy truck and all. He’d pay the guys and take off. The GI then come runnin’ to the first MP station and he’d say, “Somebody stole my truck en route.” We’d finally find it someplace after the Frenchman unloaded. And there wasn’t a thing left in it. We don’t know if it was stole or whether he sold it. He was with his outfit in Belgium by the time we found it. There was no follow-up at all, because there was so many people over and so much going on.

A lot of the GIs had respect for the MP and a lot of ’em hated our guts. Just like policemen. Worse, because we were the only ones who bothered ’em. The policemen in Paris didn’t bother the GIs at all. If they were tearin’ the place apart, they’d call us. We’d arrest ’em for anything from murder of another GI or civilian to sellin’ one of those trucks.

In London, we got thirteen colored soldiers assigned to our outfit. That was the first time they had MPs mixed, colored and white. The only reason we got it was the colored congregated out in the Limehouse district and we couldn’t do a thing with ’em. We lost a man in one of those places. It was Lichfield, headquarters of the Ninth Air Force. That’s where the colored were support troops. They build the bridges, they build the airfield, they take this metal stripping and lay it across a bog. Not combat. They were second-class citizens from the word go, whether in the army or not. They had about two or three combat units. One of ’em was air force, made out of the college in Alabama, Tuskegee. They were in Italy and they had one of the best records, a terrific record.

A lotta these colored MPs were very nice. This Morton was originally from Alabama. Him and this big white master sergeant from Alabama, they’d call each other all kinda names, just two of ’em, back and forth. This sergeant’d say, “You people haven’t been out of the jungle long enough to have your rights,” or somethin’ like that. And Morton’d say, “How do you know your ancestors weren’t in a jungle?”

Our outfit was made up of Indiana, Ohio, and Michigan. And Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama. There was a hellabaloo about who was gonna work with them colored guys. They didn’t know what to do about it. So they said to me, “You’re in charge of us tonight. Who you gonna put these guys with?” We had six of these colored guys go on duty that night. And I got hillbillies. First time they’d ever been away from home. Them Georgia boys said, “Sure, I’ll work with a nigger.” They didn’t say colored or Negro. They’d tell me, “If they selected the guys, they must be pretty good guys.” And they got along from then on, them Georgia guys and them colored guys. There wasn’t a one of ’em refused me. I had two of these guys from Kalamazoo, Michigan, and I said, “Will you work with one of them colored guys?” “Jesus Christ, no.” Y’see, them Georgia guys played with ’em as kids. They knew more about ’em than guys from the North.

In Paris, we’d go to these hotels to check on GIs AWOL. They’s women galore up these four, five stories and stairs in the middle all the way. Rooms. All you’d do is take your flashlight and look under. If you’d see GI shoes, you’d know there’s a GI in the room. (Laughs.) You open the door and nine times outa ten, the French gal would get under the covers and try to hide herself. (Laughs.) A lot of AWOLs from the colored quartermaster outfit.

There were more coloreds in Paris than white. The French women thought as much of a colored guy as they did of a white guy. Naturally they would go AWOL and they would get a French woman, a white woman, and probably that was forbidden where the colored guy come from.

Toward the end of that war, they wasn’t a guy in any of those outfits, black or white, that wouldn’t go AWOL. They had a damn hard job keepin’ those guys up in front as they did winnin’ a war. And boy, they’d kill ya, too, they’d kill an MP that interfered with’em. They was outfits that towards the end of the war, they had to put ’em in straitjackets (laughs) in order to keep ’em in line. I went to North Africa to pick up prisoners there and come back across. When my outfit come to Fort Shanks, it’s up in the hills north of New York City, up the Hudson, I looked up to see they had guys with rifles or machine guns walkin’ beats on both sides of the thing. I said, “What in the hell are those guys doin’ up there?” And they said, “To keep them infantry outfits that were goin’ overseas.” They’d go into them woods and away they’d go.

It burnt me up. I said to the lieutenant, “What in the hell are we doin’, MPs and half of us guys have been overseas and back again, why are they guardin’ us?” He said, “They guard everybody that comes into that thing,” because they had so many AWOL. It was ’42.

When we picked these guys up in Paris, we would go over to headquarters in England. They’d court-martial the guys there. Them guys were goin’ AWOL in every direction. Mostly colored guys were tried. There was always a colonel, a major, and a captain—about five or seven at a court-martial. You could tell these guys were top kicks in the regular army. The first time I went to testify, this colonel was in charge. I said this guy wasn’t guilty of selling anything. He was just picked up because he happened to be there. The colonel said, “Was he a nigger?” He didn’t say Negro, he said nigger. I said, “He was colored.” And he said, “Well, if he’s a nigger, he’s guilty, too.” I don’t know what they give them guys, because we never waited for the verdict. This could go on and on. Stealin’ government property, they could have ’em sent to the firing squad.

Do you know any guys who were shot for something like that?

Oh yes. They shot some of those guys up there that were—if you’d go to a municipal court, they’d dismiss the case. Depending a lot upon the commanding officer. The men that were shot and hung in Shepton Mallet—that was the place Henry the Fifth cut all the gals’ heads off. It was close to evening when we’d get there, because of train connections from London.

Those colored guys we got from Lichfield, they had a truck loaded with GI stuff. They’d stolen some of that. Anyway, the things they would shoot you for were incidental compared to a civilian law. Jesus, the Articles of War book looks like a Bible. They can shoot you in wartime for nothin’. Murder and rape, I think they hung. They’d execute ’em the next morning at six o’clock. They might be five or six of ’em shot. Sometimes they’d get five years. I don’t know what they done to most of the guys I brought in. I don’t know where the hell they sent ’em.

I first started takin’ em out of Goode Street. It’s somethin’ like a holding tank for criminals. When we’d get ’em, we’d leave London with ’em. Normally, they would send two of us MPs when we went to Shepton Mallet. This particular time I was alone. Sergeant says to me, “This guy’s gonna be shot.” He would handcuff me to that guy, left hand. You had your gun on your right side. He was a kind of half-past-eight guy anyway. I don’t know what the hell he was in there for, but he was supposed to be shot. I think he killed another GI. He was out of this world. Maybe he was doin’ it deliberately, I don’t know.

dp n="407" folio="391" ?The conductor told me when he let us off, “You’re only a short distance away from Shepton Mallet”. I look and it’s down in the boondocks. The prisoner was more worried than I was. I got a man handcuffed to me that’s under death sentence, gonna be shot the next day. I didn’t know whether to shoot him right forthwith or wait till he started somethin’ . (Laughs.) You don’t know how them scuffles gonna come out. Oh, I was tempted a couple times to shoot him. But I sat down alongside him because it was a matter of life and death. That guy might have a knife. I didn’t search him, the sergeant did. I certainly was scared, yes.

Why they sent me alone, I don’t know. That burnt me up as the war was goin’ on. They probably sent fifty MPs layin’ around the barracks, not doin’ a damn thing, and here I was out in the boondocks with this guy handcuffed to me.

I said, I might just as well get these cigarettes out. My wife run a grocery store at the time, she sent me a fifty-tin of Lucky Strikes. I give this guy a pack of cigarettes when I turned him over to the sergeant, who come by with a carryall to pick us up. The sergeant asked me if I want to come in tomorrow morning at six o’clock and this guy would be shot. This guy was standin’ right there. I told him no, I didn’t want to see anybody shot. He said, “Well, some guys that bring ’em down like to stay and watch ’em shot.”

The thought popped into my mind that when you’re supposed to shoot a guy, they have five or six guys and only one guy’s loaded with live ammunition. It gives a guy the feeling that he didn’t shoot nobody. He said, “Don’t let anybody shit you. Every one of them rifles is loaded. When you fire, there ain’t no blanks there.”

I never liked to see anybody executed or anybody shot. I was a policeman for thirty-one years. I saw a lotta suicides and a lotta murders. How foolish it is to take a life. One boom and that’s it. You can’t say, Wait, come back here, bullet, after it’s been fired one time. I wouldn’t give you a nickel to see a shooting or a hanging.

I saw the hangman in Paris, France. He looked so odd. He had on a wide-brimmed hat, they called ’em campaign hats, and a full-dress uniform. He was a master sergeant. An American. They had to have their own hangman. He was a professional, stationed in Texas. He’d bring his own rope. He wouldn’t talk. In other words, he was a ghost, as far as I was concerned. He wouldn’t talk to nobody. They brought him into Paris there and I guess he hung two guys. I don’t know if this Slovik28 is one I arrested or not. The kid they shot for desertion. Eisenhower says that’s the only guy that was ever executed for it. That’s what burns me up, when a gross of them that I know of were executed for probably more minor things than what Slovik was. They said he was the only one. We had to make a show of it. The son-of-a-bitches.

How goddamn foolish it is, the war. They’s no war in the world that’s worth fightin’ for, I don’t care where it is. They can’t tell me any different. Money, money is the thing that causes it all. I wouldn’t be a bit surprised that the people that start wars and promote ’em are the men that make the money, make the ammunition, make the clothing and so forth. Just think of the poor kids that are starvin’ to death in Asia and so forth that could be fed with how much you make one big shell out of.

This European war was cruel, no question about it. But the airplane has come in its own, nuclear weapons ... We don’t be in this world for long.

JOSEPH SMALL

On the night of July 17, 1944, two transport vessels loading ammunition at the Port Chicago (California) naval base on the Sacramento River were suddenly engulfed in a gigantic explosion. The incredible blast wrecked the naval base and heavily damaged the small town of Port Chicago, located 1½ miles away. Some 320 American sailors were killed instantly. The two ships and the large loading pier were totally annihilated. Windows were shattered in towns 20 miles away and the glare of the explosion could be seen in San Francisco, some 35 miles away. It was the worst home-front disaster of World War Two.... Of the navy personnel who died in the blast, most—some 200 ammunition loaders—were black.

Somerset, New Jersey. “We have a very quiet community here. The neighbor on my right is white. The neighbor on my left is black. We watch each other’s property. ” The small homes, mostly frame, indicate a working-class neighborhood.

“I do repairs on homes. I’m a carpenter, electrician, a plumber, a painter, a paperhanger. Whatever. I like working with my hands. I picked ’em up along the way, trial and error. ”

He is a devout Christian. On the wall, enframed: “All Things Work Together for Good to Them That Love God. ” In the front yard is an old church bus, which he drives. Bible Way Church Worldwide, Trenton, New Jersey. “I’m also an auto mechanic. I rebuilt the engine. ”He wasn’t always religious. “I was a man of the world until 1968. In 1968, I heard the gospel preached in its fullness, and I heeded the word of God and was baptized in Jesus’ name. Since 1968, I’ve been saved. ”

I went into the navy in 1943. I left Great Lakes, Illinois, as an apprentice seaman and was shipped to Port Chicago, California. It was a naval ammunition depot. Everybody above petty officer was white. All of the munition handlers was black. We off-loaded ammunition from boxcars and loaded it on ships. We handled every type of ammunition that was being shipped overseas, from .30-caliber ammunition shells to five-hundred-pound bombs. We worked around the clock, twenty-four hours, three shifts.

I was an ammunition handler until they discovered that I had the ability to operate a winch. I had no training, but from close observation of the winch operator, I learned how to do it. If I watch somebody do it, I’ll do it.

There was constant discussion by the men about the dangers. We got into arguments frequently. I personally had several altercations with my superior. I always received an answer: If it explodes, you won’t know anything about it.

The explosives came on boxcars. When we first got there, we loaded only on one side. The ship was moored on one side. It later expanded to a ship on either side of the dock. We were pitted one against the other divisions. If my division put on three thousand tons of ammunition during our shift, the next division had to beat that tonnage. We were pushed by our officers. They bet between them as to what division would put on the most tonnage at any given time.

We complained that it would add danger to the already dangerous job. But we were assured that since there were no detonators in any of the shells or bombs, it was impossible for them to go off. None of us believed that.

We worked under these conditions because we had no alternative. If you complained, you got KP or you got restricted to the base or you got extra duty. We were sailors, under government jurisdiction. So we worked.

Now, there was an attempt...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- OTHER BOOKS BY STUDS TERKEL

- Dedication

- NOTE

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- BOOK ONE

- BOOK TWO

- BOOK THREE

- BOOK FOUR

- EPILOGUE:

- Copyright Page