- 959 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

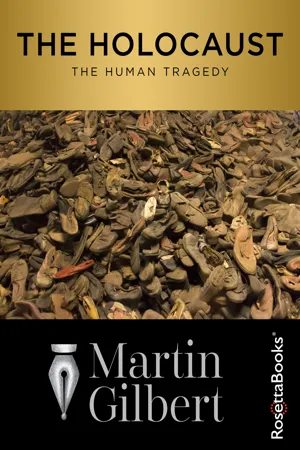

The renowned historian weaves a definitive account of the Holocaust—from Hitler's rise to power to the final defeat of the Nazis in 1945.

Rich with eyewitness accounts, incisive interviews, and first-hand source materials—including documentation from the Eichmann and Nuremberg war crime trials—this sweeping narrative begins with an in-depth historical analysis of the origins of anti-Semitism in Europe, and tracks the systematic brutality of Hitler's "Final Solution" in unflinching detail. It brings to light new source materials documenting Mengele's diabolical concentration camp experiments and documents the activities of Himmler, Eichmann, and other Nazi leaders. It also demonstrates comprehensive evidence of Jewish resistance and the heroic efforts of Gentiles to aid and shelter Jews and others targeted for extermination, even at the risk of their own lives.

Combining survivor testimonies, deft historical analysis, and painstaking research, The Holocaust is without doubt a masterwork of World War II history.

"A fascinating work that overwhelms us with its truth . . . This book must be read and reread." —Elie Wiesel, Nobel Peace Prizing–winning author of Night

Rich with eyewitness accounts, incisive interviews, and first-hand source materials—including documentation from the Eichmann and Nuremberg war crime trials—this sweeping narrative begins with an in-depth historical analysis of the origins of anti-Semitism in Europe, and tracks the systematic brutality of Hitler's "Final Solution" in unflinching detail. It brings to light new source materials documenting Mengele's diabolical concentration camp experiments and documents the activities of Himmler, Eichmann, and other Nazi leaders. It also demonstrates comprehensive evidence of Jewish resistance and the heroic efforts of Gentiles to aid and shelter Jews and others targeted for extermination, even at the risk of their own lives.

Combining survivor testimonies, deft historical analysis, and painstaking research, The Holocaust is without doubt a masterwork of World War II history.

"A fascinating work that overwhelms us with its truth . . . This book must be read and reread." —Elie Wiesel, Nobel Peace Prizing–winning author of Night

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

HistoriaSubtopic

Historia del Holocausto1

First steps to iniquity

For many centuries, primitive Christian Europe had regarded the Jew as the ‘Christ-killer’: an enemy and a threat to be converted and so be ‘saved’, or to be killed; to be expelled, or to be put to death with sword and fire. In 1543, Martin Luther set out his ‘honest advice’ as to how Jews should be treated. ‘First,’ he wrote, ‘their synagogues should be set on fire, and whatever does not burn up should be covered or spread over with dirt so that no one may ever be able to see a cinder or stone of it.’ Jewish homes, he urged, should likewise be ‘broken down or destroyed’. Jews should then be ‘put under one roof, or in a stable, like Gypsies, in order that they may realize that they are not masters in our land.’ They should be put to work, to earn their living ‘by the sweat of their noses’, or, if regarded even then as too dangerous, these ‘poisonous bitter worms’ should be stripped of their belongings ‘which they have extorted usuriously from us’ and driven out of the country ‘for all time’.1

Luther’s advice was typical of the anti-Jewish venom of his time. Mass expulsion was a commonplace of medieval policy. Indeed, Jews had already been driven out of almost every European country including England, France, Spain, Portugal and Bohemia. Further expulsions were to follow: in Italy Jews were to be confined to a special part of the towns, the ghetto, and, in Tsarist Russia, to a special region of the country, the ‘Pale’. Expulsion and oppression continued until the nineteenth century. Even when Jews were allowed growing participation in national life, however, no decade passed without Jews in one European state or another being accused of murdering Christian children, in order to use their blood in the baking of Passover bread. This ‘blood libel’, coming as it did with outbursts of popular violence against Jews, reflected deep prejudices which no amount of modernity or liberal education seemed able to overcome. Jew-hatred, with its two-thousand-year-old history, could arise both as a spontaneous outburst of popular instincts, and as a deliberately fanned instrument of scapegoat politics.

The Jews of Europe reacted in different ways to such moments of hatred and peril. Some sought complete assimilation. Some fought to be accepted as Jews by local communities and national structures. Others struggled to maintain an entirely separate Jewish style of life and observance, with their own communities and religious practice.

The nineteenth century seemed to offer the Jews a change for the better: emancipation spread throughout Western Europe, Jews entered politics and parliaments, and became integrated into the cultural, scientific and medical life of every land. Aristocratic Jews moved freely among the aristocracy; middle-class Jews were active in every profession; and Jewish workers lived with their fellow workers in extreme poverty, struggling for better conditions. But in Eastern Europe, and especially in the Polish and, even more, the Ukrainian provinces of the Tsarist Europe, anti-Jewish violence often burst out into physical conflict, popular persecution, and murderous pogrom. Here, in the poorest regions of Tsarist Russia, church and state both found it expedient, from their different standpoints, to set the Jew aside in the popular mind as an enemy of Christianity and an intruder in the life of the citizen. Jealousies were fermented. Jewish ‘characteristics’ were mocked and turned into caricatures. The Jew, who sought only to lead a quiet, productive and if possible a reasonably comfortable life, was seen as a leech on society, even when his own struggle to survive was made more difficult by that society’s rules and prejudices.

These eastern lands where prejudice was most deeply rooted spread from the Baltic to the Black Sea. Their most densely populated regions were White Russia, the Volhynia, Podolia and the Ukraine. In these regions there had existed throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth a four-tiered social structure, from which was to emerge the most savage of all wartime hatreds. At the top of this structure was the Pole: the ‘Pan’, the landowner, Roman Catholic, Polish-speaking. Next was the Ukrainian peasant: the ‘Chlop’, adherent to the Russian Orthodox faith, Ukrainian-speaking. Next was the Volksdeutsch, or Ethnic German: descendant of German settlers who had been brought to these regions in the eighteenth century, farmer, Protestant, German-speaking. Fourth, and, in the eyes of each of the other three, last, was the Jew: resident in those regions for just as long, if not longer, eking out an existence as a pedlar or merchant, Jewish by religion, and with Yiddish as his own language, ‘Jewish’ also by speech.

No social mobility existed across these four divides. By profession, by language and by religion, the gulfs were unbridgeable. Pole, Ukrainian and Ethnic German had one particular advantage: each could look to something beyond the imperial and political confines of Tsarist Russia in order to assert his own ascendancy, and could call upon outside powers and forces to seek redress of wrongs and indignities. The Jew had no such avenue of redress, no expectation of an outside champion. Unable to seek help from the emerging Polish or Ukrainian nationalisms, or from German irridentism, he lacked entirely the possibility each of the other three had, that war, revolution and political change might bring about better times.

The four-tier structure of Pole, Ukrainian, Ethnic German and Jew ensured that the conditions of assimilation and emancipation which came into being in Western Europe after the French Revolution did not exist, and could not exist, east of the River Bug; that the ideals and opinions which benefited Jew and non-Jew alike throughout Western Europe in the hundred years following the destruction of the remnants of the medieval ghetto system, and much more, by Napoleon, failed to penetrate those regions in which by far the largest number of Jews were living in the hundred years between Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo and the First World War.

In the war which came to Europe in August 1914, Jews served in every army: and on opposite sides of the trenches and the wire. German Jews fought and died as German patriots, shooting at British Jews who served and fell as British patriots. Of the 615,000 German Jews in 1914, more than 100,000 served in the German army, although before 1914 Jews could enter the military academies only with difficulty, and certain regiments almost entirely excluded Jews. Man for man, the Jewish and non-Jewish war casualties were in an almost exact ratio of the respective populations. Jews and non-Jews alike fought as Germans: for duty and for the Fatherland.

The first member of the German parliament to be killed in action was a Jew, Dr Ludwig Haas, member for Mannheim: one of twelve thousand German Jews to fall on the battlefield in German uniform.2 Jews in the Austro-Hungarian army fought Jews in the Russian, Serbian and Italian armies. When the war ended in November 1918, Jewish soldiers, sailors and airmen had filled the Rolls of Honour, the field hospitals and the military cemeteries, side by side with their compatriots under a dozen national flags.

After 1918, within the new frontiers of post-war Europe, Jews found themselves under new flags and new national allegiances. The largest single Jewish community was in the new Polish state. Here lived more than three million Jews, born in the three empires destroyed in the war: the Russian, the Austro-Hungarian and the German. In the new Hungarian kingdom lived 473,000 Jews. A similar number lived in the enlarged Rumania, and only slightly more, perhaps 490,000, in Germany. Czech Jewry numbered 350,000; French Jewry, 250,000. Other communities were smaller.

The security of the new borders depended upon alliances, treaties, and the effectiveness of the newly created League of Nations, whose covenant not only outlawed war between states, but also guaranteed the rights of minorities. In each state, old or new, the Jews looked to the local laws for protection as a minority: for equal rights in education and the professions; and for full participation in economic life.

Even as the First World War ended on the western front, more than fifty Jews were killed by local Ukrainians in the eastern Polish city of Lvov. In the then independent Ukrainian town of Proskurov, seventeen hundred Jews were murdered on 15 February 1919 by followers of the Ukrainian nationalist leader, Simon Petlura, and by the end of the year, Petlura’s gangs had killed at least sixty thousand Jews. These Jews were victims of local hatreds reminiscent of Tsarist days, but on a scale unheard of in the previous century. In the city of Vilna, the ‘Jerusalem of Lithuania’, eighty Jews were murdered during April 1919; in Galicia, five hundred perished.3 ‘Terrible news is reaching us from Poland,’ the Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann wrote to a friend on 29 November 1918. ‘The newly liberated Poles there are trying to get rid of the Jews by the old and familiar method which they learnt from the Russians. Heartrending cries are reaching us. We are doing all we can, but we are so weak!’4

On 18 December 1919 a British diplomat wrote an account of one such episode, during which Poles had killed a number of Jews suspected of Communist sympathies, and arrested many others. The Jewish women who had been arrested, but who had been exempted from execution, he noted, ‘were kept in prison without trial and enquiry. They were stripped naked and flogged. After the flogging they were made to pass naked down a passage full of Polish soldiers. Then, on the following day, they were led to the cemetery where those executed were buried, and made to dig their own graves, then, at the last moment, they were told they were reprieved; in fact, the gendarmerie regularly tormented the survivors.’ The victims, added the diplomat, ‘were respectable lower middle-class people, schoolteachers and such like’.5

In Germany, in the immediate aftermath of the First World War, Jews were among those active in rebuilding the broken nation. Hugo Preuss, Minister of Interior of the new government, prepared the draft of the Weimar Constitution, one of the most democratic in post-war Europe. Another Jew, Walther Rathenau, served as Weimar’s Minister of Reconstruction, and then as Foreign Minister.

But in the turmoil of defeat, voices were raised blaming ‘the Jews’ for Germany’s humiliation. In Berlin, the nation’s capital, there were clashes between Jews and anti-Semites: ‘Indications of growing anti-Semitism’, the Berlin correspondent of The Times reported on 14 August 1919, ‘are becoming frequent.’6

A manifestation of this anti-Semitism was shown by one of Germany’s new and tiny political parties, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, the NSDAP, soon better known as the ‘Nazi’ Party, after the first two syllables of ‘National’—Nazional. The party’s twenty-five-point programme was published in Munich on 25 February 1920, at a time when it had only sixty members. The essence of its programme was nationalistic, the creation of a ‘Great Germany’, and the return of Germany’s colonies, which had been lost at the time of Germany’s defeat. Point Four was a racialist one: ‘None but members of the Nation’, it read, ‘may be citizens of the State. None but those of German blood, whatever their creed, may be members of the Nation. No Jew, therefore, may be a member of the Nation.’7 Another point demanded that all Jews who had come to Germany since 1914 should be forced to leave: a demand which would affect more than eighteen thousand Jews, most of them born in the Polish provinces of Tsarist Russia.

The anti-Jewish sections of the Nazi Party’s programme had been drafted by three members. One of them, Adolf Hitler, was number seven in the party’s hierarchy. A former soldier on the western front, he had been wounded and gassed in October 1918, less than a month before the war’s end. On 13 August 1920, Hitler spoke for two hours in a Munich beer cellar on the theme, ‘Why we are against the Jews’. During his speech, he promised his listeners that his party, and his party alone, ‘will free you from the power of the Jew!’ There must, he said, be a new slogan, and one not only for Germany—‘Anti-Semites of the World, Unite! People of Europe, Free Yourselves!’—and he demanded what he called a ‘thorough solution’, in brief, ‘the removal of the Jews from the midst of our people’.8

A year later, on 3 August 1921, Hitler set up a group within the Nazi Party whereby he would control his own members and harass his opponents. This Sturmabteilung, or ‘Storm Section’ of the party, was quickly to be known as the SA; its members as Stormtroops. These Stormtroops were intended, according to their first regulations, not merely to be ‘a means of defence’ for the new movement, but, ‘above all, a training school for the coming struggle for liberty’. Stormtroops were to defend party meetings from attack, and, as further regulations expressed it a year later, to enable the movement itself ‘to take the offensive at any given moment’.9 Brown uniforms were designed; their wearers soon becoming known as Brownshirts. Parades and marches were organized. The party symbol became the Hakenkreuz, or swastika, an ancient Sanskrit term and symbol for fertility, used in India interchangeably with the Star of David, or Magen David, whose double triangle had long signified for the Jewish people a protective shield, and had become since 1897 a symbol of Jewish national aspirations.

From the Nazis’ earliest days, the swastika was held aloft on flags and banners, and worn as an insignia on lapels and armbands.

By the time of the establishment of the Stormtroops, membership of the Nazi Party had risen to three thousand. Hatred of the Jews, which permeated all Hitler’s speeches to his members, was echoed in the actions of his followers. Individual Jews were attacked in the street, and at public meetings and street-corner rallies Jews were blamed, often in the crudest language, for every facet of Germany’s problems including the military defeat of 1918, the subsequent economic hardship, and sudden, spiralling inflation.

Hitler’s party had no monopoly on anti-Jewish sentiment. Several other extremist groups likewise sought popularity by attacking the Jews. One target of their verbal abuse was Walther Rathenau, who, as Foreign Minister, had negotiated a treaty with the Soviet Union. Street demonstrators sang, ‘Knock off Walther Rathenau, the dirty, God-damned Jewish sow.’ These were only words, but words with the power to inspire active hatred, and on 24 June 1922, Rathenau was assassinated.

Following Rathenau’s murder, Hitler expressed his pleasure at what had been done. He was sentenced to four weeks in prison. ‘The Jewish people’, he announced on 28 July 1922, immediately on his release, ‘stands against us as our deadly foe, and will so stand against us always, and for all time.’10 In 1923, a Nuremberg Nazi, Julius Streicher, launched Der Sturmer, a newspaper devoted to the portrayal of the Jews as an evil force. Its banner headline was the slogan: ‘The Jews are Our Misfortune’.

On 30 October 1923 Arthur Ruppin, a German Jew who had earlier settled in Palestine, noted in his diary, while on a visit to Munich, how ‘the anti-Semitic administration in Bavaria expelled about seventy of the 350 East European Jews from Bavaria during the past two weeks, and it is said that the rest will also be expelled before too long.’11

On 9 November 1923 Hitler tried, and failed, to seize power in Munich. Briefly, he had managed to proclaim a ‘National Republic’. He was arrested, tried for high treason, and on 1 April 1924 sentenced to five years in detention.

After less than eight months in prison, Hitler was released on parole. During those eight months he had begun a lengthy account of his life and thought. Entitled Mein Kampf, My Struggle, the first volume was published on 18 July 1925. In it, the full fury of Hitler’s anti-Jewish hatred was made clear...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- 1 First steps to iniquity

- 2 1933: the shadow of the swastika

- 3 Towards disinheritance

- 4 After the Nuremberg Laws

- 5 ‘Hunted like rats’

- 6 ‘The seeds of a terrible vengeance’

- 7 September 1939: the trapping of Polish Jewry

- 8 ‘Blood of innocents’

- 9 1940: ‘a wave of evil’

- 10 War in the West: terror in the East

- 11 January–June 1941: the spreading net

- 12 ‘It cannot happen!’

- 13 ‘A crime without a name’

- 14 ‘Write and record!’

- 15 The ‘final solution’

- 16 Eye-witness to mass murder

- 17 20 January 1942: the Wannsee Conference

- 18 ‘Journey into the unknown’

- 19 ‘Another journey into the unknown’

- 20 ‘If they have enough time, we are lost’

- 21 ‘Avenge our tormented people’

- 22 From Warsaw to Treblinka: ‘these disastrous and horrible days’

- 23 Autumn 1942: ‘at a faster pace’

- 24 ‘The most horrible of all horrors’

- 25 September–November 1942: the spread of resistance

- 26 ‘To save at least someone’

- 27 ‘Help me get more trains’

- 28 Warsaw, April 1943: hopeless days of revolt

- 29 ‘The crashing fires of hell’

- 30 ‘To perish, but with honour’

- 31 ‘A page of glory… never to be written’

- 32 ‘Do not think our spirit is broken’

- 33 ‘One should like so much to live a little bit longer’

- 34 From the occupation of Hungary to the Normandy landings

- 35 ‘May one cry now?’

- 36 July–September 1944: the last deportations

- 37 September 1944: the Days of Awe

- 38 Revolt at Birkenau

- 39 Protectors and persecutors

- 40 The death marches

- 41 The ‘tainted luck’ of survival

- EPILOGUE: ‘I will tell the world’

- Notes and sources

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Holocaust by Martin Gilbert in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia del Holocausto. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.