- 145 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Haunted Alabama Battlefields

About this book

Discover Civil War history—and supernatural mystery—in this paranormal tour. Includes photos.

Alabama is no stranger to the battles and blood of the Civil War, and nearly every eligible person in the state participated in some fashion. Some of those citizen soldiers may linger still on hallowed ground throughout the state.

War-torn locations such as Fort Blakely National Park, Crooked Creek, Bridgeport, and Old State Bank have chilling stories of hauntings never before published. In Cahawba, Colonel C.C. Pegue's ghost has been heard holding conversations near his fireplace. At Fort Gaines, sentries have been seen walking their posts, securing the grounds years after their deaths. Sixteen different ghosts have been known to take up residence in a historic house in Athens. Join author Dale Langella as she recounts the mysterious history of Alabama's most famous battlefields and the specters that still call those grounds home.

Alabama is no stranger to the battles and blood of the Civil War, and nearly every eligible person in the state participated in some fashion. Some of those citizen soldiers may linger still on hallowed ground throughout the state.

War-torn locations such as Fort Blakely National Park, Crooked Creek, Bridgeport, and Old State Bank have chilling stories of hauntings never before published. In Cahawba, Colonel C.C. Pegue's ghost has been heard holding conversations near his fireplace. At Fort Gaines, sentries have been seen walking their posts, securing the grounds years after their deaths. Sixteen different ghosts have been known to take up residence in a historic house in Athens. Join author Dale Langella as she recounts the mysterious history of Alabama's most famous battlefields and the specters that still call those grounds home.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

THE SACK OF ATHENS, THE BATTLE OF ATHENS AND SULPHUR CREEK TRESTLE

Athens, Alabama, was a pivotal location in Civil War history. There were many skirmishes and battles that took place there; however, one battle in Athens was destined to change the Civil War forever.

In this section, in order to tell you the story as it truly unfolded, I cannot sugarcoat or embellish the reality of this war. In the following story, I depict the true nature of what happened on those sad days. My intent is only to share the story with you how it is regarded in Civil War history. To tell it any other way would not portray the realistic details of the war in Athens just as it happened so long ago. Some of the following part of this story may be slightly disturbing, but it is my intention to tell the story just how it was. It is my hope that this may help create a larger vision of why there are so many restless spirits still remaining at these battle sites that are angry, upset, sad, mourning or even trying to communicate messages with the living.

In earlier periods of history, treating the enemy with compassion after the battle, showing mercy to civilians or sparing lives on the losing side wasn’t even a thought. If the captives were not killed, they were often made prisoners or slaves. It was not until the seventeenth century that some suggested that captives should be treated humanely. We find in war that there is a tendency to dehumanize the enemy, and people just become abstract. Is this the only way to get ordinary people to kill the enemy? Is there really a moral way to fight any war? Did the North and South have an “idealized” version of what “war” was really all about and what it meant to be a soldier? Do newly enlisted soldiers really know the reality of warfare? Is whether your side wins all that matters?

Some veterans of warfare often speak of the true conditions of war, such as seeing a blinding flash a few yards in front of them causing them to fall flat on their face. Soon enough, they realized that a number of the infantry were carrying mines strapped to the small of their backs or that mines were planted in certain areas, unbeknownst to unsuspecting soldiers. If any rifle or bullet struck one or a soldier stepped on one causing it to explode, it would blow the man into three pieces—two legs and a head and a chest. The insides and other pieces of human beings became litter, spread across the battlefield—headless bodies, legs, arms and shoes with feet still in them. Some found it nearly impossible to even walk yards without stepping on or over death. Many soldiers come back from war traumatized, as in the case of my military friend who couldn’t even stay at the Selma reenactment with us because the sounds of the battle, guns and cannons triggered an internal reaction causing his posttraumatic stress disorder to surface.

Many innocent people have suffered in warfare because officers and soldiers wanted revenge or felt that they could do whatever they wanted. Were the conditions of war the reasons they became this way? Starving, deprived, horrified and exposed soldiers—is this what happened to the troops under the command of Colonel Turchin at the Sack of Athens?

What happened in Athens was an atrocity. It was a pivotal point in the war, making the Northern and Southern conflict a total war. After capturing the Memphis & Charleston Railroad and the victory at Shiloh, the Union army moved deep into the Confederacy’s homeland. The town of Athens, Alabama, possessed an important depot on the Nashville & Decatur Railroad line that would prove both strategic and beneficial to the Union army.

On April 27, 1862, two Ohio units moved in to occupy the town. There were about nine hundred residents in Athens, Alabama, and they offered to cooperate with the Union because they claimed to be pro-Union; however, the sudden infiltration of Union troops into North Alabama shocked Southern folks. The Union troops, however, had a false sense of security that occupying Athens would be all right. They thought that the presence of the Union army would be greeted warmly since the citizens of Athens had voted for a Northern Democrat in the 1860 election, because of their pro-Union sentiments and due to Athens mayor W.P. Tanner’s statement that after the state left the Union, the Union flag continued to soar on top of the courthouse for two months. Tanner also noted that the town’s residents found the Union soldiers to be orderly and restrained, so the Union thought that the town’s citizens had previously displayed considerable Unionist sentiment. But what the Union troops really found when they got there was that many residents in Athens had turned on the Union cause and were actually anti-Union.

On the morning of May 1, 1862, the Confederate First Louisiana Cavalry organized an attack on the Union garrison in Athens, Alabama. The Confederate cavalry drove the Union bluecoats from the town, forcing them back toward Huntsville, Alabama. There were cheers and the waving of hats and handkerchiefs, as well as spitting and cursing at the Union soldiers. More than one hundred residents joined with the Confederate soldiers to remove the Union soldiers from the town. Upon returning to the town, the First Louisiana Cavalry members were received as heroes.

However, the next day, just as the Confederates were settling back in town, commanding officer Colonel John Basil Turchin, feeling very betrayed, led a counterattack with the Eighth Brigade, consisting of the Eighteenth Ohio, Thirty-seventh Indiana, Nineteenth Illinois and Twenty-fourth Illinois. The Union forces pushed the Confederates back out of Athens once again.

Turchin was a military-trained Russian, and he believed that the residents’ behavior in the pro-Union town was treacherous conduct. In retaliation, he decided to punish the citizens. He rode into the town square and loudly told his troops, “I shut my eyes for two hours. I see nothing.” The soldiers, including foreign soldiers, were both angry and tired, so they sacked the whole town.

Businesses were looted and destroyed. The drugstore’s medical library in addition to surgical and dental instruments were destroyed. Shop windows were shattered, while jewelry stores, druggists and dry goods stores were vandalized and burglarized. After that, the criminal activity continued on to the terrified private residents. The soldiers searched for valuables while pocketing gold watches, jewelry and silver utensils. Clothing drawers were pulled to the floor, and trunks were pried open with bayonets. Some soldiers just sought out food rations, such as tobacco, sugar and molasses. The officers and soldiers insulted the men and women of the town, although physical violence was kept to a minimum. Soldiers fired their gun into a residential home, unknowingly resulting in a pregnant woman losing her baby. In fact, both the mother and fetus died. Indecent propositions were made to the women of the town, and the soldiers were accused of raping one fourteen-year-old enslaved girl and attempted to rape another servant girl.

When night came, soldiers claimed private homes while chopping roasts on pianos and cutting bacon on the rugs before going to bed. The damage was estimated to be about $55,000. These horrific events became known as the “Sack of Athens.” This undoubtedly fueled the animosity between the Southerners and Northerners, as well as a disgust for foreign soldiers.

Young boy soldier in portrait. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

In 1862, the action initiated on the part of Colonel Turchin and his troops was deeply shocking to American soldiers and civilians; this was supposed to be a gentleman’s war. What happened on May 2, 1862? Did both the North and South set a heavy burden of expectation and values on the volunteer soldier to abide by a commitment to duty, knightliness, bravery, manliness and, most of all, honor while trying to maintain their aggression, fear, self-control and restraint—all while enduring the brutal environmental conditions of war? Was this really an ideal vision of “war”? The Nineteenth Illinois Infantry, one of the units involved in the savaging of Athens, was formed with the help of prewar Illinois militia companies; it reflected such values by requiring its men to swear that they would not enter a saloon, brothel or billiard parlor. It’s safe to say that they were not taught to be brutes.

The Union army’s reaction to the events that took place during the Sack of Athens and toward Colonel Turchin’s behavior was very aggressive. Upon hearing of the incident, area commander General Ormsby Mitchel immediately rushed to the town, met with the victimized residents, promised to punish those responsible and encouraged the residents to establish a committee to complain against the soldiers. However, Mitchel also understood the frustration the forces were under because of Athens residents’ betrayal and the Confederates’ hit-and-run tactics.

Major General Don Carlos Buell called the incident an undisputed atrocity and ordered Turchin and his men court-martialed to examine the charges against them. For ten days, Colonel Turchin sat before the court-martial while the citizens of Athens testified regarding the abuse they had suffered at the hands of his troops. Brigadier General James A. Garfield was ordered to preside over the trial, initially believing that Turchin’s men had committed the most shameful outrages on the country ever seen during the Civil War. Some believed that Turchin’s Russian military training had made him too brutal.

In the weeks after the events in Athens, it was found that Turchin disobeyed both Buell’s discipline and orders to protect all private property by ordering his men to burn the nearest farmhouse whenever they were fired on from ambush. Regarding the charges and in his defense, Turchin stated, “I have tried to teach the rebels that treachery to the Union was a terrible crime,” he said. “My superior officers do not agree with my plans. They want the rebellion treated tenderly and gently. They may cashier me, but I shall appeal to the American people and implore them to wage this war in such a manner as will make humanity better for it.”

Brigadier General James A. Garfield received a letter from his wife that reflected the public’s view of the proceedings: “I hope you will find Col. Turchin guilty of nothing unpardonable,” she wrote. “Severity and sternness should be turned to the punishment of rebels for the barbarities committed on our boys rather than to the punishment of our own. It seems very strange that as soon as a man begins to accomplish something in the way of putting down the rebellion he is recalled, or superseded, or disgraced in some way.”

The Civil War’s goal had been to restore the Southern states to the Union. The rebellion was seen as the action of hotheaded minority Southerners. To gain support for the war, newspapers began to criticize the Rebels with rumors of atrocities against Union soldiers. Northerners claimed that the brutal and savage Southern slave systems made Southerners different from other Americans.

Turchin was found guilty but returned to Chicago, Illinois, a hero because of his harsh administration of war directed against the citizens of the South. General Buell ordered Turchin dismissed from the army, but Turchin announced that instead of being removed from the service, President Abraham Lincoln had overturned the verdict of the court and promoted him to the rank of Brigadier General. Turchin himself called for enlisting slaves against their masters. He commanded in the Battles of Stone River, Chickamauga and Chattanooga. In 1864, he retired due to his war wounds.

Many Northerners despised General Don Carlos Buell because of his determination to protect Southern property. His proslavery sentiments found him relieved of command in October 1862. President Lincoln had lost confidence in Buell’s judgment because Buell had attempted to scourge Turchin and because he did not aggressively pursue the Confederate army after the Battle of Perryville. The Union army refused to pay a penny of the $54,689 claimed by the victims of Turchin’s visit. The Sack of Athens escalated the Civil War. A Chicago veteran of the Athens incident later recalled, “It was pitiful, but it was war.”

This 1862 incident was a turning point in the war because Turchin’s promotion gave other Union commanders the go-ahead to show the South the full weight of the war. General William T. Sherman’s army, Turchin and his men and other Union units, including volunteers, were now seemingly free to invade and would no longer offer any apologies for doing what they had come to do. The act of depriving the Confederacy of needed provisions accelerated the end of the Civil War; however, it also became engrained in the Southern memory.

In the fall of 1863, the Federal army began recruiting black males to serve in the United States Colored Troops Infantry Regiments, the 106th, 110th and 111th USCT. They were primarily freed or runaway slaves from North Alabama and southern Tennessee. In order to protect the railroad, in early 1863, Fort Henderson was constructed in Athens, Alabama, on Coleman Hill. It was an earthwork 180 feet by 450 feet and was protected by the 18th Ohio from Athens.

As part of the continuing fight between the Confederates and Union forces in Athens, Alabama, the Battle of Sulphur Creek Trestle took place from September 23 to September 25, 1864. Some people refer to this conflict as the “Battle of Athens.”

After Lieutenant General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s involvement in and relative victory against Streight’s Raid, Forrest eventually led his force back into northern Alabama and middle Tennessee to disrupt the crucial supply of provisions, supplies, troops, clothing, ammunition and other necessities for General William T. Sherman’s army, which was stationed in Georgia. Forrest also wanted to stop the return of damaged goods and wounded soldiers back to Chattanooga. The Alabama & Tennessee Railroad ran from Nashville, Tennessee, through southern Tennessee and northern Alabama to Huntsville and Decatur on the banks of the Tennessee River. From Decatur, the railroad connected with another railroad that extended east into Chattanooga. This line thus provided continuous passage for troop supplies that came off boats on the Cumberland River in Nashville and were sent to support Union forces in Chattanooga. Forrest’s force grew (with the addition of General Roddy’s men) to about 4,500 soldiers, but he then sent the Twentieth and Fourteenth Tennessee Cavalry to Tanner, Alabama, leaving himself with fewer men.

At sunset on September 23, Forrest and his remaining soldiers moved in to check out the town and Fort Henderson. Just before dark, Colonel Wallace Campbell and six hundred men consisting of the 106th, 110th and the 111th United States Colored Troops defended the fort by firing their artillery. Forrest’s command consisted of Bell’s and Lyon’s brigades of Buford’s division; Rucker’s brigade; some of Roddy’s troops; Biffle’s brigade; the 4th Tennessee; and Colonel Nixon’s regiment. The Confederates made several attempts to gain possession of the town. The quartermaster’s building and the commissary building were both burned down by the Confederates, and by late into the night, the Union troops had taken up safety at Fort Henderson. Under the cover of darkness, another five hundred men of the 3rd Tennessee (Union) moved into the fort. The fort, considered to be the best to resist any field battery between Nashville and Decatur, was an earthworks bastion fort with five points measuring 180 feet by 450 feet. It was 1,350 feet in circumference and was surrounded by an abatis of fallen trees, a 4-foot palisade and a 12-foot-wide ditch.

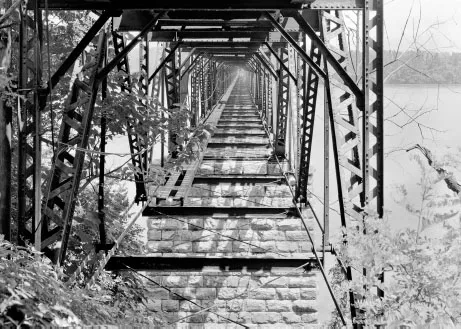

The railroad bridge on the Alabama & Tennessee Railroad that ran from Nashville, Tennessee, to Huntsville and Decatur, Alabama, on the banks of the Tennessee River. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

On September 24, 1864, at about 7:00 a.m., the Confederate army opened fire on Fort Henderson with twelve-pound batteries stationed on both the north and west sides. Forrest’s artillery officer opened fire with his eight guns, casting almost sixty shells into the fort but doing very little damage. The Union fought back with two twelve-pound howitzers. At about 9:00 p.m., two demands for surrender sent in under General Forrest were refused by the Union force. At that point, Forrest asked to have a personal meeting with Colonel Campbell to show Campbell that his Union forces were completely outnumbered. Forrest tricked Campbell and told him that he had about ten thousand men at his side, and he demanded surrender.

Meanwhile, General Granger of Decatur had organized and sent 350 soldier reinforcements by railroad early the next morning to help reinforce the garrison in Athens. However, because the railroad along the way to Athens had been taken overnight by Confederate forces, when the Union units arrived early the next morning, they were attacked by Buford’s division. The Union troops fought the Confederates while driving them back, all the way up to about three hundred feet from the fort. Unfortunately, by the time they got to the fort, they found that Colonel Campbell had surrendered about half an hour earlier.

The surrender of the fort allowed the Confederates to turn their attention to the relief troops from Decatur, the 18th Michigan and 102nd Ohio Infantry. After three hours of fighting and suffering casualties of one-third their total soldiers, the Union forces surrendered. Forrest’s men had captured 1,300 prisoners, three hundred horses, two pieces of artillery and a large amount of supplies. The Union officers claimed that Campbell should have never surrendered the fort because they had ample supplies to last them a siege of at least ten days while awaiting reinforcements. They said that the water well in the fort had plenty of water, and there were 70,000 rounds of elongated ball cartridges, an ample supply of cavalry carbines and 120 rounds for each of the howitzers. The Union officers said that the surrender was against their wishes. The Federal loss was 106 killed and wounded; Confederate loss was equal to the force engaged.

On September 24, 1864, after the victorious defeat of Union forces in Athens, Forrest advanced north with about five hundred cavalry and infantry soldiers intending to destroy the strategic railroad trestle at Sulphur Creek, located about six miles north of Athens. The trestle stood 71 feet high and stretched 561 feet across a deep gorge. The battle over the Sulphur Creek Trestle railroad bridge would be the bloodiest land battle to take place in Alabama during the war.

Union forces of the Ninth Indiana Cavalry and Tenth Indiana Cavalry had constructed a fort at Sulphur Trestle in order to protect the vulnerable railroad supply line....

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- The Siege of Bridgeport

- The Battle of Fort Blakely

- The Battles of Day’s Gap, Crooked Creek and Hog Mountain

- The Battle of Selma

- The Battle of Mobile Bay

- The Battle of Fort Mims

- The Battle of Horseshoe Bend

- The Battle of Decatur

- The Sack of Athens, the Battle of Athens and Sulphur Creek Trestle

- Additional Civil War Haunted Stories in Alabama

- Bibliography

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Haunted Alabama Battlefields by Dale Langella in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.