- 321 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"In this satisfying, lyrical memoir," an American woman discovers her true faith—and true love—by converting to Islam and moving to Egypt (

Publishers Weekly).

Raised in Boulder, Colorado, G. Willow Wilson moved to Egypt and converted to Islam shortly after college. Having written extensively on modern religion and the Middle East in publications such as The Atlantic Monthly and The New York Times Magazine, Wilson now shares her remarkable story of finding faith, falling in love, and marrying into a traditional Islamic family in this "intelligently written and passionately rendered memoir" ( The Seattle Times, 27 Best Books of 2010).

Despite her atheist upbringing, Willow always felt a connection to god. Around the time of 9/11, she took an Islamic Studies course at Boston University, and found the teachings of the Quran astounding, comforting, and profoundly transformative. She decided to risk everything to convert to Islam, embarking on a journey across continents and into an uncertain future.

Settling in Cairo where she taught English, she soon met and fell in love with Omar, a passionate young man with a mild resentment of the Western influences in his homeland. Torn between the secular West and Muslim East, Willow—with her shock of red hair, shaky Arabic, and Western candor—struggled to forge a "third culture" that might accommodate her values as well as her friends and family on both sides of the divide.

Part travelogue, love story, and memoir, "Wilson has written one of the most beautiful and believable narratives about finding closeness with God" ( The Denver Post).

Raised in Boulder, Colorado, G. Willow Wilson moved to Egypt and converted to Islam shortly after college. Having written extensively on modern religion and the Middle East in publications such as The Atlantic Monthly and The New York Times Magazine, Wilson now shares her remarkable story of finding faith, falling in love, and marrying into a traditional Islamic family in this "intelligently written and passionately rendered memoir" ( The Seattle Times, 27 Best Books of 2010).

Despite her atheist upbringing, Willow always felt a connection to god. Around the time of 9/11, she took an Islamic Studies course at Boston University, and found the teachings of the Quran astounding, comforting, and profoundly transformative. She decided to risk everything to convert to Islam, embarking on a journey across continents and into an uncertain future.

Settling in Cairo where she taught English, she soon met and fell in love with Omar, a passionate young man with a mild resentment of the Western influences in his homeland. Torn between the secular West and Muslim East, Willow—with her shock of red hair, shaky Arabic, and Western candor—struggled to forge a "third culture" that might accommodate her values as well as her friends and family on both sides of the divide.

Part travelogue, love story, and memoir, "Wilson has written one of the most beautiful and believable narratives about finding closeness with God" ( The Denver Post).

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Butterfly Mosque by G. Willow Wilson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religious Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

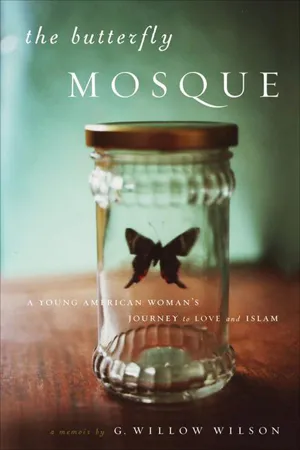

The Butterfly Mosque

The Far Mosque is not built of earth

and water and stone, but of intention and wisdom

and mystical conversation and compassionate action.

—Rumi (translated by Coleman Barks)

DURING THE WINTER AND SPRING THAT FOLLOWED, OMAR and his family shepherded me as little as possible so that I could have a degree of the American independence I was used to. I consider that year my Arab childhood, because I was allowed to make the same social, practical, and religious mistakes a child is allowed to make, and afterward, though I had an unusual degree of leeway and support, I was expected to shoulder the responsibilities of a married Arab woman. Omar’s Uncle Ahmad, a successful businessman and head of the extended family, said after our engagement was announced that no one was to question my integrity—what is commonly called honor—and that anyone who did would fall under his displeasure, and that everyone was to be as patient and understanding as they knew how.

I wanted to deserve that confidence. So I corrected and overcorrected when I was accidentally rude, which happened often during the first several months: I would wander into gatherings of the family chiefs (where I would be doted on with amusement and offered coffee until someone came to collect me), forget to help aunts and cousins with chairs and plates and food, and get into the wrong kind of political discussion with elders to whom I was expected to defer on all points.

What I lacked in poise I tried to make up for in dedication. I would sit through a five-hour wake in near-silence, dance at a wedding until my feet ached, and listen to the stories my grandmother-in-law told with complete attention but without understanding more than one word in three. The joy that this brought my family-by-marriage made adjusting to middle-class Egyptian life seem like a light burden. To this day an auntie will occasionally grab me and gather me in her lap like an overgrown baby and tell me I am the beloved of her heart. In those moments I forget how exhausted I have been, and think there is nothing I would not be willing to do for the people—in Egypt and at home—who have loved and defended me.

I would need them in the months that followed. At first, it seemed as though the break through that December was the sum total of what needed to happen to make everybody comfortable. But goodwill is not enough. Between my culture and Omar’s was a pit full of dangers: poverty, terrorism, wars of attrition, racism, colonialism, and malice. Egyptians were furious that their American “allies” preached democracy at gunpoint in Iraq, yet allowed democratic Egyptian reformers to rot in jail under the regime of President Mubarak. The sense of having been humiliated and deceived by the West was overpowering, and it had not very subtle effect on how Egyptians treated westerners. As a result, I have seen countless American expatriates come to the Middle East with what they thought were open minds and hearts, contracted to work in schools or NGOs and bright-eyed with the desire to heal the warring civilizations, only to be rejected and humiliated by the people they set out to help. They turn around and go home, adding first-hand experience to the ranks of anti-Arab cynics.

They fail to realize that people who have lost dignity and opportunities to the “clash of civilizations” cannot be expected to welcome peacemakers who have lost nothing. That anger has to go somewhere. Pampered expatriates are convenient targets for spite. Had I not had a pressing reason to stay, I, too, might have become cynical and left. Omar’s family embraced me, and my colleagues accepted me, but the rest of Egypt would not be so charitable.

Shortly after our parents’ Christmas visit, Jo and I moved out of our expensive apartment in Maadi and into a much smaller one in Tura. This way, Omar and I could live closer together, and Jo and I could save money. In describing Tura I have to remember that for many of its inhabitants, living there is an accomplishment. The real slums of Cairo are far worse. Omar’s family spent part of his early childhood in one of them. He describes having to cross rivers of sewage on his way to school, and going days without running water or electricity as the badly maintained—and often pirated—utility infrastructure blinked on and off. His family did not own a telephone until he was ten years old.

Compared to this, Tura must have seemed like a breath of fresh air: planned, paved streets, regular and fairly solid buildings, reliable water and lights. Sohair worked with a diligence I can only envy and a courage I fear I will never have to buy the flat where she lived with her sons. Despite our differences, I admire the tenacity of the people who live in Tura; many of them have stories similar to Sohair’s, and have spent the better part of their lives pulling themselves up from poverty through very hard work.

The area has improved a little since I lived there. Today there are small gardens around the military-owned apartment complex where we rented our flat, and in some buildings the stairs have been tiled and the elevators are maintained. When Jo and I moved there, though, the situation was more stark. On the outside, the neighborhood looked worse than the worst American slum I had ever seen. Garbage was strewn in heaps at the edge of potholed parking lots; the institutional apartment buildings were dark and filthy, and their crumbling cement stairs were dotted with cat excrement and bits of bone and gristle the animals had pulled from bags of refuse. The air was thick with industrial fumes and at times became almost unbreathable, causing lymph nodes under one’s ears, chin, and arms to swell painfully. Tura is sandwiched between three landmarks: an infamous political prison, a cement factory, and the Nile. Until it was immortalized in Alaa Al Aswany’s novel The Yacoubian Building, Tura was known only by its proximity to the factory, and is still commonly referred to as Tura El-Esment, Tura of the Cement.

I remember it as a harrowing, sunless place, and whenever I say the name aloud a perfectly formed memory surfaces: I am trudging through the filthy dust outside the prison with a bag of fruit in my arms, and when I look up at the dun-colored, wire-topped walls, I am acutely conscious of the journalists, reformists, and dissidents being held inside. Then I see the mosque, a little jewel-like thing that looks far older than the prison itself. Its corniced minaret stretches above the wall like a plea for help; the mosque, like the prisoners, was trapped there for no other reason than that it was in the way.

I never learned its name. In Cairo there is a mosque on almost every street corner, so only the largest and oldest are given memorable titles; the rest are most often called by their cross streets. Omar and his family had lived in the neighborhood for years and never learned the name of the mosque behind the prison wall. When I had been in Tura for several weeks, I began to call it the butterfly mosque, because it reminded me of a butterfly caught in a jar. I would fantasize about freeing it and imprisoning in its place the modern, ugly, loud mosque that was the focal point of Turan religious activity, and was visible (appropriately enough) from the bathroom window of the flat Jo and I shared.

This mosque we quickly came to hate. Its muezzin announced the five daily prayer times in gravelly shrieks, broadcast at full volume over a set of speakers that were comically expensive and well-maintained when compared to the degree of poverty in which so many of the mosque’s attendees lived. To call this institution a fundamentalist mosque sounds almost tongue-in-cheek; it was rabidly conservative, and if it had been situated in a less neglected neighborhood, there’s a chance its leaders would now reside in the prison just a half-kilometer away. As it was, Tura was a convenient location for extremism to fester, and so we awoke promptly at four a.m. every morning to the screams of the muezzin, who rattled windows and set dogs to howling for a considerable radius. Few people ever complained. Most were too afraid of the extremists to speak up; the rest were too worn down by the brutality of daily life in a poor neighborhood in a police state to be bothered. And daily life was brutal. There is no kinder word for it.

Tura was a neighborhood that required capitulation and assimilation. It was not enough to be good natured or attentive or even Muslim; to be accepted there we would have had to convert to the church of lower-middle-class Cairo, a badly educated, puritanical segment of society. The fundamentalists south of Tura at least had a measure of idealism; the conservatism of our neighbors arose from undiluted desperation. Theirs was a culture of suspicion, grasping and covetous, whose elaborate rules and limitations were the products of minds ever-conscious of the nearness of ruin, the very real possibility that one’s family could slip back into poverty. No one was comfortable, no one was safe, and so Jo and I, with our strange clothing and papery skin and alarming habits, were considered threatening.

When Omar warned us that Tura was much more conservative than our old neighborhood, and said we should pay a little more attention, we readily agreed, but the fact of the matter is that we had no idea what to pay attention to. “More conservative” to us meant that we should both be home when male guests came over and avoid wearing T-shirts or tight pants. We didn’t know “more conservative” meant that two single women had no business living alone, and if by circumstance they were forced to do so, they should have no contact of any kind with the opposite sex, make as little noise as possible, and not go out at night.

I don’t think Omar realized this either. The Middle East is one place for men, and an entirely different place for women. He was almost as puzzled and alarmed as we were by the neighborhood’s summary rejection of its two palest residents. It would take me months to understand why we inspired so much fear, and to guess at the questions my neighbors must have been asking themselves. Would we cheat someone, lead someone’s son astray, or call down the wrath of our infamous embassy, and in doing so ruin a family? The place breathed panic, and we added to that panic, and so we were hated.

I clung to politeness on principle. One Friday afternoon I was buying fruit from a local vendor—dusty oranges, which, when peeled, gave off a delicious scent at odds with the general odor of factory fumes—when the latest prayer session let out at the fundamentalist mosque and a column of men trickled through its doors into the hazy light. I kept my eyes downcast and tried to avoid them, but found myself caught between a man and his small son, who had wandered a few feet away from his father.

“As-salaamu alaykum,” I said to the man, thinking it would be ruder to say nothing. He stared at me for a moment before wordlessly gathering his son in his arms. I flushed and looked around, hoping no one had overheard. Refusing to return this traditional greeting is one of the worst insults one can offer a fellow Muslim. I hurried home.

When I described what had happened to Omar, he didn’t believe me.

“He was probably just confused,” he said. “He doesn’t expect as-salaamu alaykum from a foreign woman.”

“But I was wearing a head scarf.”

“Perhaps he thought you were wearing it to be culturally sensitive.”

“Omar, he looked right at me.”

Omar reached over to play with the hem of my sleeve. “I get so worried about you,” he said. “If I had known—it’s not usual for people to behave this way. They don’t behave this way to one another.”

It was true. Sohair’s immediate neighbors, who were familiar with my situation, were very kind to me. And I saw my own neighbors being kind to each other. But it was small comfort.

A few days after we moved in, I woke up to a ringing doorbell, so late at night that it was almost early. Unnerved, I stayed as I was, cocooned in the stained blue quilt that matched my stained blue mattress. After a pause, the ringing continued. Because she could sleep through anything, Jo had taken the room looking out to the busy road that ran along the Nile, so I wasn’t surprised when her light stayed off. Fumbling in the dark, I pulled on a robe and went to the door. Through the peephole I saw a guard and one of the local zabelleen, the Cairene untouchables, whose lives and livelihood revolve around the collecting and sorting of the city’s garbage. I hesitated in the doorway. By Egyptian rules, I was well within my rights not to answer; I was a woman, they were two men, it was the middle of the night. On the other hand, refusing to answer did not necessarily mean the men would leave. Since one of the men was a military guard, it could be important—I wouldn’t have put it past the local authorities to announce a fire by sending long-winded delegations door-to-door. I opened mine a crack.

“Aiwa?” I asked coldly.

“Mise’ al’khayr hadritik,” responded the guard, using the polite form of you. The zabell stood with his eyes politely downcast. The two men didn’t look especially threatening, so I stayed to listen. The zabell, I gathered, after his request was simplified several times, wanted to buy an ancient, broken vacuum we had found in a closet and put outside to be salvaged. I stared at him.

“Just take it,” I said, baffled.

“Really?” asked the guard.

“Yes, for God’s sake, good-bye.”

He apologized and I shut the door and went back to bed.

The next morning, I caught up with Omar in the staff room at school and told him the story.

“The weirdest thing happened last night,” I said, trying to decide whether I should be casual or serious and settling on casual. “A guard came to our door at two in the morning with one of the zabelleen, trying to buy that old vacuum we found.”

He leaned forward. “What?” There was carefully restrained anger in his voice. I tried to hide my uneasiness.

“Yeah, they showed up like it was the middle of the afternoon on market day—”

“He came to your door in the middle of the night with another man?”

I could sense something was very wrong.

“Yes.”

Omar stood up abruptly. “I have to make a phone call,” he said, taking out his mobile.

“Was that bad?” I asked, feeling ridiculous.

“That was a test,” he said curtly, and headed for the door.

On the bus home I pressed him for details, but he was evasive. Eventually I gathered that the military guards who patrolled our complex liked to press their advantage with inhabitants they perceived to be weak. They were attempting nothing so overt as rape or theft, but something psychological—in international politics and on their own streets, westerners bullied them; now they had a chance to bully vulnerable western women. Better yet, one of these women was about to become a member of an Egyptian family, which presented its own unique possibilities.

Outside the luxurious world of expatriates and the westernized elite, a middle-class Egyptian family functions as a chain forged to protect intangible (and for a westerner, unthinkable) virtues like honor and status—which, in reality, represent that family’s influence over whatever tiny corner of the Egyptian socioeconomy they’ve managed to carve out for themselves. The guards had identified me as my new family’s weakest link. Now they were out to discover how far I could be pushed and, by extension, how far Omar could be pushed.

Omar, as it turned out, could not be pushed at all. He went to the local administrative office, and the result was the sentencing of the guard in question to eight days in prison. Omar came back to our apartment and told Jo and me this, as a reassurance.

“Prison?” Jo looked at me anxiously.

I bit my lip. I wanted to resolve the situation but I couldn’t stand the thought of sending anyone behind that awful half-kilometer of dun walls and barbed wire.

“I’m not sure anyone needs to go to prison over this,” I said. “I really feel like he was just being an idiot to see what he could get away with—I don’t think he was out to hurt anyone.”

“It will teach him a lesson,” muttered Omar, but I could see he was beginning to waver. Later, he would argue with the guard’s commanding officer on his behalf, and the sentence would be reduced to a pay suspension.

Despite Jo’s and my fervent prayers, the guard was not transferred to another building. He continued to sit in our filthy concrete lobby like a two-legged Cerberus, chanting the Quran and glaring at us with open hostility as we passed. Relief only came in the early morning, when he slept on his stool with a blanket pulled over his head. We learned to tiptoe around him when we left for school in the chill of seven a.m.

After this falling-out with our guard, Jo and I began to rely heavily on the goodwill of the local grocers, who ran a duken on a side street near our building. Since there was no local coffeehouse, possibly due to the influence of the fundamentalists, the duken was the default center of local life. Everyone passed through its doors to buy their eggs, olives, cheese, and bread, as well as cooking oil and matches and other household necessities. For some reason—I don’t know what, though I am thankful for it—the grocers took pity on us and it was because of them that our stay in Tura was not completely unbearable.

I was nervous around them at first; I had learned better than to be too open with any man to whom I had not been formally introduced. For the first few weeks I practically snuck around the store, collecting all the things I needed instead of asking the shop boy, and avoiding eye contact whenever possible. It was not always an easy maneuver. In college I took modern standard Arabic, the language of the press; the colloquial dialect of Egypt used a completely different vocabulary. In order to understand the label on a packet of beans, I had to stare at it for several minutes, which gave other people in the shop ample time to stop whatever they were doing and stare at me. One day, when I was scrutinizing the labels above a row of spice jars, I heard a voice over my shoulder.

“Erfa,” it said, and a hand pointed to one of the jars. I looked up wildly. It was one of the grocers. He was about thirty, had a mustache, and was smiling mildly. “Ismaha erfa,” he repeated.

“Shokran,” I muttered.

“Afwan,” said the grocer gently. “W’da camoon.

Camoon.” “Camoon,” I repeated, cumin. E...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Prologue

- Kun

- The White Horse

- The Conqueress City

- Road Nine at Twilight

- Ramadan

- The Bowl of Fire

- A Tree in Heaven

- Meetings in the Desert

- Arrivals and Confessions

- The Butterfly Mosque

- Zawaj Figaro

- Arabic Lessons

- Iran

- The Shrine of Fatima

- El Khawagayya

- Divisions and Lines

- Land of the Free

- Nile Wedding

- An Appointment

- Women

- The Fourth Estate

- The Sheikha

- Fracture

- The Oracle of Siwa

- Flood Season