- 420 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

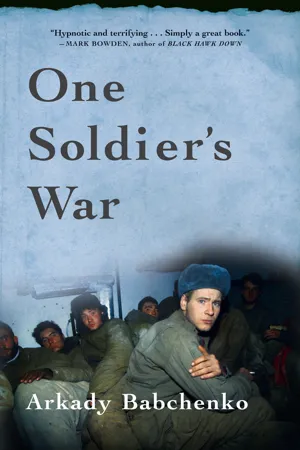

One Soldier's War

About this book

A visceral and unflinching memoir of a young Russian soldier's experience in the Chechen wars.

In 1995, Arkady Babchenko was an eighteen-year-old law student in Moscow when he was drafted into the Russian army and sent to Chechnya. It was the beginning of a torturous journey from naïve conscript to hardened soldier that took Babchenko from the front lines of the first Chechen War in 1995 to the second in 1999. He fought in major cities and tiny hamlets, from the bombed-out streets of Grozny to anonymous mountain villages. Babchenko takes the raw and mundane realities of war the constant cold, hunger, exhaustion, filth, and terror and twists it into compelling, haunting, and eerily elegant prose.

Acclaimed by reviewers around the world, this is a devastating first-person account of war that brilliantly captures the fear, drudgery, chaos, and brutality of modern combat. An excerpt of One Soldier's War was hailed by Tibor Fisher in The Guardian as "right up there with Joseph Heller's Catch-22 and Michael Herr's Dispatches." Mark Bowden, bestselling author of Black Hawk Down, hailed it as "hypnotic and terrifying" and the book won Russia's inaugural Debut Prize, which recognizes authors who write despite, not because of, their life circumstances.

"If you haven't yet learned that war is hell, this memoir by a young Russian recruit in his country's battle with the breakaway republic of Chechnya, should easily convince you." — Publishers Weekly

In 1995, Arkady Babchenko was an eighteen-year-old law student in Moscow when he was drafted into the Russian army and sent to Chechnya. It was the beginning of a torturous journey from naïve conscript to hardened soldier that took Babchenko from the front lines of the first Chechen War in 1995 to the second in 1999. He fought in major cities and tiny hamlets, from the bombed-out streets of Grozny to anonymous mountain villages. Babchenko takes the raw and mundane realities of war the constant cold, hunger, exhaustion, filth, and terror and twists it into compelling, haunting, and eerily elegant prose.

Acclaimed by reviewers around the world, this is a devastating first-person account of war that brilliantly captures the fear, drudgery, chaos, and brutality of modern combat. An excerpt of One Soldier's War was hailed by Tibor Fisher in The Guardian as "right up there with Joseph Heller's Catch-22 and Michael Herr's Dispatches." Mark Bowden, bestselling author of Black Hawk Down, hailed it as "hypnotic and terrifying" and the book won Russia's inaugural Debut Prize, which recognizes authors who write despite, not because of, their life circumstances.

"If you haven't yet learned that war is hell, this memoir by a young Russian recruit in his country's battle with the breakaway republic of Chechnya, should easily convince you." — Publishers Weekly

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

TWO

11/The Runway

We lie at the edge of the runway, Kisel, Vovka, Tatarintsev and I, our bare bellies turned up to the sky. They made us march over from the station a few hours ago and now we wait to see what will happen next.

Our boots stand in a row, our puttees spread out on top to dry as we soak up the sun’s rays. It seems we have never been so warm in our lives. The yellow tips of the dry grass prick our backs and Kisel plucks a blade with his toes, turns onto his stomach and crumbles it in his hands.

‘Look, dry as a bone. Back in Sverdlovsk they’re still up to their necks in snow,’ he marvels.

‘It sure is warm,’ agrees Vovka.

Vovka is eighteen, like me, and looks like a dried apricot—dark-complexioned, skinny, tall. His eyes are black and his eyebrows are fair, bleached by the sun. He comes from the south of Russia, near Anapa, and volunteered to go to Chechnya thinking this would take him closer to home.

Kisel is twenty-two and was drafted into the army after college. He’s good at physics and math and can calculate sinusoids like nobody’s business. Only what’s the use of that now? He’d be better off knowing how to put on his puttees properly—he has white flabby skin and still manages to walk his feet to a bleeding mess because they are poorly wrapped. Kisel is due to be demobilized in six months and had no wish to be sent to Chechnya. All he wanted was to serve out his time somewhere in central Russia, near his hometown of Yaroslavl, but it wasn’t to be.

Next to him sits Andrei Zhikh, fat-lipped and small, the puniest soldier in our platoon, which earned him the nickname Loop, after the little leather ring where you tuck the loose end of a soldier’s belt. He’s no more than five feet tall but he puts down enough food for four. Where it all goes is a mystery, and he stays small and skinny like a dried cockroach. What strikes you about him are those huge doughnut lips that can suck down a can of condensed milk in one go and which turn his soft Krasnodar accent into a mumble, and his stomach, which swells up to twice its size when Loop stuffs it with food.

To his right sits Vic Zelikman, a Jew who is more terrified than any of us of getting roughed up by the older soldiers. We are all afraid of this, but the puny, cultured Zyuzik, as we call him, takes the beatings particularly badly. In a year and a half of army service he still can’t get used to the fact that he is a nonperson, a lowlife, a dumb animal, and every punch sends him into a depression. Now he sits thinking about how they will beat us here, wondering if it’ll be worse than during training or not as bad.

The last member of our group, Ginger, is a quiet, sullen, stocky guy with huge hands and flaming red hair. Or rather he used to have flaming red hair before the barber got to him. Now his bald soldier’s head looks like it’s strewn with copper filings, as if someone filed a pipe over it. All he cares about is how to get the hell out of here faster.

Today we managed to eat properly for the first time. The officer in charge of our group, a swarthy major who shouted at us all the way here, is sitting a good distance away in the middle of the field. We make the most of this and wolf down our dry rations.

Back on the train the only food the major had given us was a small tin of stewed meat for each day of the journey, and our stomachs were now pinched with hunger. When we halted briefly on spur lines to allow other trains through there wasn’t enough time to distribute the bread and we were hungry all the time.

So as not to swell up from the pangs we swapped our boots for food. Before we left we had all been issued with new lace-up parade boots. ‘I wonder where they think we’ll be doing parade marching in Chechnya,’ said Loop, who was the first to trade his pair for ten cabbage pies.

The women selling food at the stations took our boots out of sheer pity. When they saw our train pull in they swarmed around with pies and home-cooked chicken. They saw what sort of train it was standing on the line, started to wail and blessed us with crosses drawn in the air, and accepted boots and long johns they had no use for in exchange for food. One woman came up to our window and silently passed us a bottle of lemonade and a couple of pounds of chocolates. She promised to bring us cigarettes, but the major shooed us away from the window and told us not to lean out any more.

In the end they didn’t manage to distribute all the bread and it simply went moldy. When we left the train in Mozdok, we walked past the bread car at the back just as they were throwing out sacks of fermented, green loaves. We grabbed what we could and managed to get more than most.

Right now our stomachs are full of stewed pork, although there was more fat than meat (Ginger assures us it’s not fat at all but melted lubricant grease mixed with boot polish), and barley oats. On top of that, we had each tucked away a whole loaf of bread, and you could say life was looking pretty rosy just then. Or at least for the next half an hour it had taken on a clear definition, beyond which no one wanted to guess what lay in store. We live only for the moment.

‘I wonder if they’ll put us straight on regular rations today,’ Loop mumbles through his doughnut lips and slips a spoon that has been licked to a clean gleam back into the top of his boot. With lunch safely in his gut he immediately starts to think about supper.

‘Are you in a hurry to get there or something?’ Vovka says, nodding at the ridge that separates us from Chechnya. ‘As far as I’m concerned, it’s better to go without grub altogether just to stay on this field a bit longer.’

‘Or stay here for good, even,’ Ginger adds.

‘Maybe they’ll assign us to baking buns,’ Loop dreams out loud.

‘Yeah, that would be right up your alley,’ answers Kisel. ‘The moment you’re let loose on a bread-cutting machine you’ll slip a loaf under each of those lips of yours and still not choke.’

‘Some bread now wouldn’t go amiss, that’s true,’ says Loop, a big grin on his face.

Back in training the swarthy major told us he was assembling a group to go and work in a bakery in Beslan, in North Ossetia. He knew how to win us over. To be assigned to a bakery is the secret dream of all new recruits, or ‘spirits,’ who have served less than six months of their two-year spell in the army. We are spirits, and they also call us stomachs, starvers, fainters, goblins, anything they like. We are particularly tormented by hunger in the first six months, and the calories we extracted in training from that gray sludge they call oatmeal were burned up in an instant on the windy drill square, when the sergeants drove us out for our ‘after-lunch stroll.’

Our growing bodies were constantly deprived of nutrition and at night we would adjourn to the toilets to secretly devour tubes of toothpaste, which smelled so appetizingly of wild strawberries.

Then one day they lined us up in a row and the major went along asking each of us in turn: ‘Do you want to serve in the Caucasus? Come on, it’s warm there, there are plenty of apples to eat.’

But when he looked them in the eye, the soldiers shrank back. His pupils were full of fear and his uniform stank of death. Death and fear. He sweated it from all his pores and he left an unbearable, stifling trail behind him as he walked around the barracks.

Vovka and I said yes. Kisel said no and told the major and his Caucasus where both of them could go. Now the three of us lie on this runway in Mozdok and wait to be taken farther. And all the others who stood in that line are here too, waiting beside us, fifteen hundred in total, almost all just eighteen years old.

Kisel is still amazed at how they duped us all so well.

‘Surely there has to be a consent form,’ he argues, ‘some kind of paper where I write that I request to be sent to the meat-grinder to continue my army service. I didn’t sign anything of the sort.’

‘What are you going on about?’ says Vovka, playing along. ‘What about the instructions for safety measures the major asked us to sign, remember? Do you ever even read what you sign? Don’t you understand anything? Fifteen hundred guys uniformly expressed a wish to protect the constitutional order of their Motherland with their lives, if need be. And seeing how our noble sentiment so moved the Motherland, we made it even easier for her and said: No need for separate consent papers for each of us, we’ll go off to war by lists. Let them use the wood they save to make furniture for an orphanage for Chechen children who suffer because of what we do in this war.’

‘You know what, Kisel?’ I say with irritation. ‘You couldn’t have signed anything and still end up here. If the order comes for you to go and bite it, then you go—so why are you going on about your precious report? Why don’t you just give me a smoke instead?’

He passes me a cigarette and we light up.

There is constant traffic on the runway. Someone lands, someone takes off, wounded soldiers wait for a flight, and people crowd around a nearby water fountain. Every ten minutes low-flying attack aircraft leave for Chechnya, groaning under the weight of munitions and then later they return empty. Helicopters warm up their engines, the hot wind drives dust across the runway, and we get jumpy.

It’s a terrible mess; there are refugees everywhere, walking across the field with their junk and telling horrific tales. These are the lucky ones who managed to escape from the bombardments. The helicopters aren’t supposed to take civilians but people take them by storm and ride standing, as if they are on a tram. One old man flew here on the undercarriage; he tied himself to the wheel and hung like that during the forty-minute flight to Mozdok from Khankala. He even managed to bring two suitcases with him.

The exhausted pilots make no exceptions for anyone and indifferently shout out the names on the flight roster, ticking people off list by list. They are beyond caring much about anything any more. Right now they’re making up passenger lists for flights to Rostov and Moscow, which might leave the day after tomorrow if they aren’t canceled.

Any remaining places are filled with the wounded. Apart from cargo, each flight can take only about ten people, and the seriously wounded get priority. Lying on stretchers, they are packed in between crates, rested on sacks or simply set on the floor, crammed in any old how just as long as they’re sent off. People trip over them and knock them off their stretchers. Someone’s foot catches a captain with a stomach injury and pulls out the drain tube, letting blood and slime run out of the hatch and onto the concrete. The captain screams, while flies descend instantly on the puddle.

There aren’t enough flights into Chechnya either. Some journalists have been waiting almost a week, and builders sunbathe here for the third day. But we sense that we will be sent today, before sunset. We aren’t journalists or builders, we are fresh cannon fodder, and they won’t keep us waiting around for long.

‘Funny old life, isn’t it?’ muses Kisel. ‘I’m sure those journalists would pay any money to get on the next flight to Chechnya, but no one takes them, while I would pay any money to stay here, where it’s better by a mile. Better still would be to get as far away from here as possible, but they’ll put me on the next flight. Why is that?’

A ‘Cow’ Mi-26 cargo helicopter lands. Our guys stormed some village and all day long they have been evacuating dead and wounded from Chechnya. They unload five silvery sacks onto the runway, one after the other. The shining bags gleam in the sun like sweets, and the wrappers are so bright and pretty that it’s hard to believe they are filled with pieces of human bodies.

At first we couldn’t work out what they were.

‘Probably humanitarian aid,’ Vovka guesses when he sees the bags on the concrete, until Kisel points out that they take aid in there, they don’t bring it back.

It finally dawned on us when a canvas-backed Ural truck drove up on the runway, and two soldiers jumped out and started loading the sacks. They grabbed them by the corners, and when the sacks sagged in the middle we realized that there were corpses inside.

But this time the Ural doesn’t come and the bodies just lie there on the concrete. No one pays any attention to them, as if they are a part of the landing strip, as if that’s the way it should be, dead Russian boys lying in the arid steppe in a strange southern town.

Two other soldiers appear in long johns cut off at the knees, carrying a bucket of water. They wipe down the Cow’s floor with rags, and half an hour later the helicopter carries the next group to Chechnya, filled to the gills once again. No one bothers to spin us any more fairy tales about baking buns in Beslan.

None of us says so, but each time we hear the heavy bee-like droning over the ridge we all think: ‘Is this really it, is it really my turn?’ At this moment we are on our own, every man for himself. Those who remain behind sigh with relief when the Cow carries off a group without them on board. That means another half an hour of life.

Carved into Kisel’s back are the words I LOVE YOU, each letter the size of a fist. The white scars are thin and neat but you can tell the knife went deep under the skin. For the past six months we have been trying to wheedle the story out of him but he tells us nothing.

Now I sense he will spill the beans. Vovka thinks so too.

‘Go on, Kisel, tell us how you got that,’ he tries again.

‘Come on, out with it,’ I say, backing him up. ‘Don’t take your secret to the grave with you.’

‘Idiot,’ says Kisel. ‘Keep your trap shut.’

He turns over again onto his back and shuts his eyes and his face clouds over. He doesn’t feel like talking but he might be thinking he could really get killed.

‘My Natasha did that,’ he says eventually. ‘Back when we first met and hadn’t yet married. We went to a party together, dancing and stuff, and a lot of drinking of course. I got well tanked up that night, dressed up like a Christmas tree in my best gear. Then I woke up next morning and the bed and sheet were covered in blood. I thought I’d kill her for doing that, but as you see, we got married instead.’

‘That’s some little lady you have!’ says Vovka, who has a girlfriend three years younger than him. They ripen fast down there in the south, like fruit. ‘You should send her down our way, they’d soon whip her into shape, literally. I’d like to see my girl try something like that. So what, you can’t even come home drunk without getting a rolling pin in the head?’

‘No, it’s not like that. My wife is actually gentle, she’s great,’ Kisel says. ‘I don’t know what got into her, she never pulled another stunt like that again. She says it was love at first sight for her, and that’s how she wanted to bind me to her. “Who else will want you now I’ve put my stamp on you,” she tells me.’ He plucks another blade of grass and chews it pensively. ‘We’ll have four kids for sure . . . Yep, when I get home I’ll rustle up four for us,’ Kisel says and then falls quiet.

I look at his back and then think to myself that at least he won’t remain unidentified and lie in those refrigerators we saw today at the station. That’s assuming his back stays in one piece.

‘Kisel, are you afraid to die?’ I ask.

‘Yes.’ He is the oldest and smartest among us.

The sunlight shines through my eyelids and the world becomes orange. The warmth sends goose bumps fluttering across my skin. I can’t get used to this. Only the day before yesterday we were in snowbound Sverdlovsk, and here it’s baking. They brought us from winter straight into summer, packed thirteen at a time into each compartment of the railroad cars, surrounded by a stinky must, bare feet dangling from the upper births. There wasn’t enough room for everyone, so we even took it in turns to sleep in pairs under the table, day and night. Wherever you looked there were piles of boots and overcoats. It was even good that the major didn’t feed us; we rode sitting for a day and a half, do...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Map

- One

- Two

- Three

- Military Abbreviations

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access One Soldier's War by Arkady Babchenko in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.