eBook - ePub

Silences

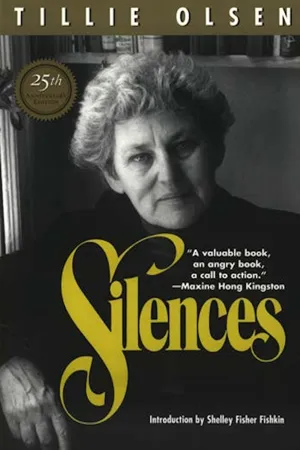

About this book

A landmark survey of disenfranchised literary voices and the forces that seek to silence them—from the influential activist and author of

Tell Me a Riddle.

With this groundbreaking work, Olsen revolutionized the study of literature by shedding critical light on the writings of marginalized women and working-class people. From the excavated testimony of authors' letters and diaries, Olsen shows us the many ways the creative spirit, especially in those disadvantaged by gender, class, or race, has been suppressed through the years. Olsen recounts the torments of Herman Melville, the shame that brought Willa Cather to a dead halt, and the struggles of Olsen's personal heroine Virginia Woolf, the greatest exemplar of a writer who confronted the forces that worked to silence her.

First published in 1978, Silences expanded the literary canon and the ways readers engage with literature. This 25th-anniversary edition includes Olsen's classic reading lists of forgotten authors and a new introduction. Bracing and prescient, Silences remains "of primary importance to those who want to understand how art is generated or subverted and to those trying to create it themselves" (Margaret Atwood, The New York Times Book Review).

"A valuable book, an angry book, a call to action." —Maxine Hong Kingston

" Silences helped me to keep my sanity many a day." —Gloria Naylor, author of Mama Day

"[ Silences is] 'the Bible.' I constantly return to it." —Sandra Cisneros, author of The House on Mango Street

" Silences will, like A Room of One's Own, be quoted where there is talk of the circumstances in which literature is possible." —Adrienne Rich, author of Diving into the Wreck

With this groundbreaking work, Olsen revolutionized the study of literature by shedding critical light on the writings of marginalized women and working-class people. From the excavated testimony of authors' letters and diaries, Olsen shows us the many ways the creative spirit, especially in those disadvantaged by gender, class, or race, has been suppressed through the years. Olsen recounts the torments of Herman Melville, the shame that brought Willa Cather to a dead halt, and the struggles of Olsen's personal heroine Virginia Woolf, the greatest exemplar of a writer who confronted the forces that worked to silence her.

First published in 1978, Silences expanded the literary canon and the ways readers engage with literature. This 25th-anniversary edition includes Olsen's classic reading lists of forgotten authors and a new introduction. Bracing and prescient, Silences remains "of primary importance to those who want to understand how art is generated or subverted and to those trying to create it themselves" (Margaret Atwood, The New York Times Book Review).

"A valuable book, an angry book, a call to action." —Maxine Hong Kingston

" Silences helped me to keep my sanity many a day." —Gloria Naylor, author of Mama Day

"[ Silences is] 'the Bible.' I constantly return to it." —Sandra Cisneros, author of The House on Mango Street

" Silences will, like A Room of One's Own, be quoted where there is talk of the circumstances in which literature is possible." —Adrienne Rich, author of Diving into the Wreck

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE—SILENCES

In Heaven a spirit doth dwell

“Whose heart-strings are a lute”;

None sing so wildly well

As the angel Israfel. . . .

And the shadow of [his] perfect bliss

Is the sunshine of ours. . . .

If I could dwell where Israfel

Hath dwelt, and he where I,

He might not sing so wildly well

A mortal melody,

While a bolder note than this might swell

From my lyre within the sky.

—Edgar Allan Poe

Had Milton’s been the lot of Caspar Hauser,

Milton would have been vacant as he.

—Herman Melville

If Goethe had been stolen away a child, and reared in a robber band in the depths of a German forest, do you think the world would have had Faust and Iphigenie? But he would have been Goethe still. At night, round their watch-fire, he would have chanted wild songs of rapine and murder, till the dark faces about him were moved and trembled.

—Olive Schreiner

If Tolstoy had been born a woman . . .

—Virginia Woolf

If. . . .

1962

SILENCES IN LITERATURE

Originally an unwritten talk, spoken from notes at the Radcliffe Institute in 1962 as part of a weekly colloquium of members. Edited from the taped transcription, it appears here as published in Harper’s Magazine, October 1965.

(Several omitted lines have been restored; an occasional name or phrase and a few footnotes have been added.)

1962

SILENCES

Literary history and the present are dark with silences: some the silences for years by our acknowledged great; some silences hidden; some the ceasing to publish after one work appears; some the never coming to book form at all.

What is it that happens with the creator, to the creative process, in that time? What are creation’s needs for full functioning? Without intention of or pretension to literary scholarship, I have had special need to learn all I could of this over the years, myself so nearly remaining mute and having to let writing die over and over again in me.

These are not natural silences—what Keats called agonie ennuyeuse (the tedious agony)—that necessary time for renewal, lying fallow, gestation, in the natural cycle of creation. The silences I speak of here are unnatural: the unnatural thwarting of what struggles to come into being, but cannot. In the old, the obvious parallels: when the seed strikes stone; the soil will not sustain; the spring is false; the time is drought or blight or infestation; the frost comes premature.

The great in achievement have known such silences—Thomas Hardy, Melville, Rimbaud, Gerard Manley Hopkins. They tell us little as to why or how the creative working atrophied and died in them—if ever it did.

“Less and less shrink the visions then vast in me,” writes Thomas Hardy in his thirty-year ceasing from novels after the Victorian vileness to his Jude the Obscure. (“So ended his prose contributions to literature, his experiences having killed all his interest in this form”—the official explanation.) But the great poetry he wrote to the end of his life was not sufficient to hold, to develop the vast visions which for twenty-five years had had expression in novel after novel. People, situations, interrelationships, landscape—they cry for this larger life in poem after poem.

It was not visions shrinking with Hopkins, but a different torment. For seven years he kept his religious vow to refrain from writing poetry, but the poet’s eye he could not shut, nor win “elected silence to beat upon [his] whorled ear.” “I had long had haunting my ear the echo of a poem which now I realised on paper,” he writes of the first poem permitted to end the seven years’ silence. But poetry (“to hoard unheard; be heard, unheeded”) could be only the least and last of his heavy priestly responsibilities. Nineteen poems were all he could produce in his last nine years—fullness to us, but torment pitched past grief to him, who felt himself “time’s eunuch, never to beget.”

Silence surrounds Rimbaud’s silence. Was there torment of the unwritten; haunting of rhythm, of visions; anguish at dying powers, the seventeen years after he abandoned the unendurable literary world? We know only that the need to write continued into his first years of vagabondage; that he wrote:

Had I not once a youth pleasant, heroic, fabulous enough to write on leaves of gold: too much luck. Through what crime, what error, have I earned my present weakness? You who maintain that some animals sob sorrowfully, that the dead have dreams, try to tell the story of my downfall and my slumber. I no longer know how to speak.*

That on his deathbed, he spoke again like a poet-visionary.

Melville’s stages to his thirty-year prose silence are clearest. The presage is in his famous letter to Hawthorne, as he had to hurry Moby Dick to an end:

I am so pulled hither and thither by circumstances. The calm, the coolness, the silent grass-growing mood in which a man ought always to compose,—that, I fear, can seldom be mine. Dollars damn me. . . . What I feel most moved to write, that is banned,—it will not pay. Yet, altogether, write the other way I cannot. So the product is a final hash . . .

Reiterated in Pierre, writing “that book whose unfathomable cravings drink his blood . . . when at last the idea obtruded that the wiser and profounder he should grow, the more and the more he lessened his chances for bread.”

To be possessed; to have to try final hash; to have one’s work met by “drear ignoring”; to be damned by dollars into a Customs House job; to have only weary evenings and Sundays left for writing—

How bitterly did unreplying Pierre feel in his heart that to most of the great works of humanity, their authors had given not weeks and months, not years and years, but their wholly surrendered and dedicated lives.

Is it not understandable why Melville began to burn work, then ceased to write it, “immolating [it]. . . sealing in a fate subdued”? And turned to occasional poetry, manageable in a time sense, “to nurse through night the ethereal spark.” A thirty-year night. He was nearly seventy before he could quit the customs dock and again have full time for writing, start back to prose. “Age, dull tranquilizer,” and devastation of “arid years that filed before” to work through. Three years of tryings before he felt capable of beginning Billy Budd (the kernel waiting half a century); three years more to his last days (he who had been so fluent), the slow, painful, never satisfied writing and re-writing of it.*

Kin to these years-long silences are the hidden silences; work aborted, deferred, denied—hidden by the work which does come to fruition. Hopkins rightfully belongs here; almost certainly William Blake; Jane Austen, Olive Schreiner, Theodore Dreiser, Willa Cather, Franz Kafka; Katherine Anne Porter, many other contemporary writers.

Censorship silences. Deletions, omissions, abandonment of the medium (as with Hardy); paralyzing of capacity (as Dreiser’s ten-year stasis on Jennie Gerhardt after the storm against Sister Carrie). Publishers’ censorship, refusing subject matter or treatment as “not suitable” or “no market for.” Self-censorship. Religious, political censorship—sometimes spurring inventiveness—most often (read Dostoyevsky’s letters) a wearing attrition.

The extreme of this: those writers physically silenced by governments. Isaac Babel, the years of imprisonment, what took place in him with what wanted to be written? Or in Oscar Wilde, who was not permitted even a pencil until the last months of his imprisonment?

Other silences. The truly memorable poem, story, or book, then the writer ceasing to be published.* Was one work all the writers had in them (life too thin for pressure of material, renewal) and the respect for literature too great to repeat themselves? Was it “the knife of the perfectionist attitude in art and life” at their throat? Were the conditions not present for establishing the habits of creativity (a young Colette who lacked a Willy to lock her in her room each day)? or—as instanced over and over—other claims, other responsibilities so writing could not be first? (The writer of a class, sex, color still marginal in literature, and whose coming to written voice at all against complex odds is exhausting achievement.) It is an eloquent commentary that this one-book silence has been true of most black writers; only eleven in the hundred years since 1850 have published novels more than twice.**

There is a prevalent silence I pass by quickly, the absence of creativity where it once had been; the ceasing to create literature, though the books may keep coming out year after year. That suicide of the creative process Hemingway describes so accurately in “The Snows of Kilimanjaro”:

He had destroyed his talent himself—by not using it, by betrayals of himself and what he believed in, by drinking so much that he blunted the edge of his perceptions, by laziness, by sloth, by snobbery, by hook and by crook; selling vitality, trading it for security, for comfort.

No, not Scott Fitzgerald. His not a death of creativity, not silence, but what happens when (his words) there is “the sacrifice of talent, in pieces, to preserve its essential value.”

Almost unnoted are the foreground silences, before the achievement. (Remember when Emerson hailed Whitman’s genius, he guessed correctly: “which yet must have had a long foreground for such a start.”) George Eliot, Joseph Conrad, Isak Dinesen, Sherwood Anderson, Dorothy Richardson, Elizabeth Madox Roberts, A.E. Coppard, Angus Wilson, Joyce Cary—all close to, or in their forties before they became published writers; Lampedusa, Maria Dermout (The Ten Thousand Things), Laura Ingalls Wilder, the “children’s writer,” in their sixties.* Their capacities evident early in the “being one on whom nothing is lost”; in other writers’ qualities. Not all struggling and anguished, like Anderson, the foreground years; some needing the immobilization of long illness or loss, or the sudden lifting of responsibility to make writing necessary, make writing possible; others waiting circumstances and encouragement (George Eliot, her Henry Lewes; Laura Wilder, a writer-daughter’s insistence that she transmute her storytelling gift onto paper).

Very close to this last grouping are the silences where the lives never came to writing. Among th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Contents

- Introduction

- PART ONE—SILENCES

- PART TWO—Acerbs, Asides, Amulets, Exhumations, Sources, Deepenings, Roundings, Expansions

- PART THREE

- Tillie Olsen’s Reading Lists

- Permissions Acknowledgments

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Silences by Tillie Olsen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Feminist Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.