- 180 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

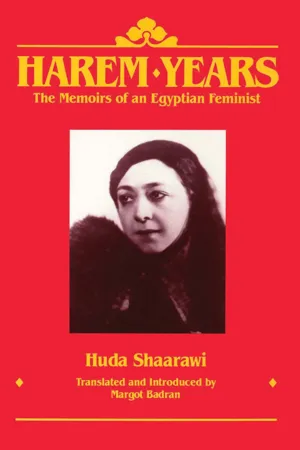

A firsthand account of the private world of a harem in colonial Cairo—by a groundbreaking Egyptian feminist who helped liberate countless women.

In this compelling memoir, Shaarawi recalls her childhood and early adult life in the seclusion of an upper-class Egyptian household, including her marriage at age thirteen.

Her subsequent separation from her husband gave her time for an extended formal education, as well as an unexpected taste of independence. Shaarawi's feminist activism grew, along with her involvement in Egypt's nationalist struggle, culminating in 1923 when she publicly removed her veil in a Cairo railroad station, a daring act of defiance.

In this fascinating account of a true original feminist, readers are offered a glimpse into a world rarely seen by westerners, and insight into a woman who would not be kept as property or a second-class citizen.

In this compelling memoir, Shaarawi recalls her childhood and early adult life in the seclusion of an upper-class Egyptian household, including her marriage at age thirteen.

Her subsequent separation from her husband gave her time for an extended formal education, as well as an unexpected taste of independence. Shaarawi's feminist activism grew, along with her involvement in Egypt's nationalist struggle, culminating in 1923 when she publicly removed her veil in a Cairo railroad station, a daring act of defiance.

In this fascinating account of a true original feminist, readers are offered a glimpse into a world rarely seen by westerners, and insight into a woman who would not be kept as property or a second-class citizen.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Harem Years by Huda Shaarawi, Margot Badran in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

THE FAMILY

CIRCASSIAN RELATIVES

We used to wait eagerly for the visits of my maternal grandmother and uncles, who came every year or two from Turkey. They would come loaded down with enormous quantities of rare treats, such as spicy salted beef called basturma, sausages, Circassian cheese, walnuts, chestnuts, and dried fruits, which we shared with our friends and neighbours.

My grandmother was short and neither fat nor thin, with blue eyes and very pale skin. She dressed all in white and covered her two plaits of white hair, nearly as long as she was, with a gauze tarha. In this incandescent whiteness she had the appearance of a saint, and the kindliness that filled her face gave it a special radiance. I loved my grandmother very much even though we did not share a common tongue and I could not communicate with her except in signs. She used to amuse me with Circassian tales and songs, many of which I remember to this day. Yusif, my elder uncle, resembled my grandmother in stature, kind expression, and gentle disposition, and was much cherished by us for his light-heartedness. My uncle, Idris, the father of Hawa and Huriyya,1 with his slender figure and beautiful face, looked more like my mother. He was a tall, graceful man of exquisite manners who lavished great love and attention upon us and spent long days in conversation with us.

Our relatives used to spend the winter with us, but with the approach of summer my grandmother would begin to show signs of suffering from the heat. Her eyes would swell, her face would flush, and she would insist on returning to Turkey. The separation always pained us.

One year, after his mother and older brother had departed, Uncle Idris remained behind to study Arabic and deepen his knowledge of Islam. My mother urged him to take a wife. When he expressed an interest in marrying an Egyptian girl and my mother arranged his betrothal to the daughter of a respected family, we all rejoiced. The date for the wedding had already been fixed, when the parents of the prospective wife made it a condition for marriage that their daughter never be required to live abroad. Uncle Idris would not agree, insisting that a wife should follow her husband wherever he might go, and thus the engagement was broken.

Years later, after my grandmother had died, Uncle Yusif married and brought his wife to Egypt for a visit. One day, I pleaded, ‘Why don’t you stay with us instead of returning to Istanbul where there is nothing to keep you after Grandmother’s death?’ With a smile he said, ‘Your father, upon him be blessings, asked me to stay the first time we came to Egypt. I did not agree, because it would have meant the disappearance of the family name in our country.’ I pressed him, ‘Is Bandirma (a port town on the Sea of Marmara) the home of your father and grandfather? Was the house you now occupy built by your father? You are from the Caucasus not Anatolia, aren’t you?’ He smiled again and said, ‘These were the very words your late father used when he urged me to settle in Egypt.’

Uncle Idris returned to settle in Turkey, where he also married. One day my two uncles and other relatives in Turkey were invited to a wedding celebration in a neighbouring village. In those parts, it was customary on such occasions to travel in ox-drawn carriages because the horses could not pull loads over the rough terrain. When my elder uncle was about to set out for the wedding he asked his brother Idris to accompany him. Since my younger uncle had guests, and could not leave immediately, he promised to follow later on his new mare. When he set out galloping, his high-spirited horse let loose and began to run away with him. The horse reared up unexpectedly. He was thrown to the ground and killed instantly.

News of this turned the rejoicing of the wedding party into mourning. He left behind two little daughters, Hawa and Hurriyya, the elder not yet two and the younger still being suckled.

MY MOTHER

My mother was a strong woman, a private person who had firm control over her emotions. She seldom complained and kept her sadnesses hidden inside. I never once dared ask my mother about her origins and how she came to Egypt. But, very eager to learn about my mother’s early life, I urged Uncle Yusif to tell me why his family had left the Caucasus and gone to Anatolia, how my mother had come to Egypt, and about her marriage to my father.

He told me that my mother’s father, Sharaluqa Gwatish, had been the renowned headman of the Shabsigh tribe. When fighting broke out between the Caucasus and Czarist Russia in the 1860s, the Circassians defended the Caucasus with singular bravery. However, my grandfather’s men were overcome and he was captured. Another tribal leader in the Caucasus, the well-known Shaikh Shamil al-Daghistani,2 an adversary of my grandfather, discredited him by circulating the story that my grandfather had betrayed his country and joined the Russians. A rival band of Circassians then seized his son Yusif, less than sixteen years old, and held him hostage under pain of execution if the allegations proved to be true. Relatives and friends of my grandfather, meanwhile, set out to rescue him from Russian captivity and save his poor, innocent son. Disguised as Russian soldiers, the Circassian rescue party which included Huriyya, the beautiful and courageous daughter of my grandfather’s brother, penetrated enemy ranks. The Russians unfortunately discovered the rescue attempt and killed or wounded most of the Circassians, who were few in number and badly equipped. Despite injuries, my grandfather continued firing at the Russians from behind the mountain rocks, while Huriyya went for help. My grandfather fought until a bullet finally killed him. The Circassian reinforcements carried his body to his birthplace for burial, thus giving lie to the slander spread by his rival, Shaikh Shamil. His son Yusif was thus spared dishonour and death.

Afterwards, my grandmother decided to leave the Caucasus. With her five young children, three boys and two girls, she joined the stream of refugees making their way to Istanbul. My uncle told me about their suffering from hunger and other bitter experiences. While the Turkish government was still processing the refugees, Jacob, the youngest boy, died from pneumonia as a result of over-exposure. When his little sister was abducted from the woman who suckled her, my grandmother decided to send her other daughter – my mother – to Egypt to be raised under the care of her maternal uncle, Yusif Pasha Sabri, an army officer.

My grandmother entrusted my mother to a friend leaving for Egypt on a visit to Raghib Bey and his family. The man was asked to take my mother to Yusif Pasha Sabri in Cairo. When they arrived, my mother’s uncle was on a military expedition abroad, and his wife (a freed slave of il-Hami Pasha3), a peculiar woman, protested her husband had no such relative and refused to accept my mother. The man then took my mother to Raghib Bey’s house to await her uncle’s return. It seems that her uncle’s wife remained silent.

My mother stayed where she was. Raghib Bey’s daughter cared for her like a daughter and took her with her when she married and set up a new household.

My mother grew into a striking beauty. Her guardian decided to marry her to a wealthy man. It was her good fortune that my father took her as his wife. One day, after she was married, she was standing near the window helping my father dress, when she began to cry. When my father asked her what was the matter, she told him she had seen a young man who looked like her brother enter the salamlik (men’s reception area). My father asked about her family and she told him her story. He then sent for Ali Bey Raghib to seek their whereabouts. My father located the man who had originally brought my mother to Egypt and dispatched him to Turkey to bring the brothers back.4

When my mother’s two maternal uncles arrived our clan expanded. The reunion changed my mother’s life.

MY FATHER

My father died when I was five years old. I have only a few memories of him, as he was often away from Cairo. I used to go to his room with Ismail, my brother from another wife, to kiss his hand every morning. We would find him sitting on his prayer rug praying or meditating. After we kissed his hand and he kissed us, he would go to his cabinet to get chocolates for us. We always left his presence beaming with joy.

My father played an important role in the political life of Egypt and rendered noble services during his long public career.5 Unfortunately, I was unable to lay my hands upon historical records to document the story. When I looked for contemporaries of my father, the only person I found who could assist me was Qallini Pasha Fahmi,6 who as a young man had been closely associated with my father during the last years of his life.

My father entered government service after receiving a letter that designated him Commissioner of the District of Qulusna in the province of Minya. He immediately went to the governor of the province to explain that he could not accept the appointment because he was acting as guardian to his brother, Ibrahim, and the children of his paternal uncle who were still young and needed his care. After much discussion, the governor confided, ‘It was your friend Hasan al-Sharii7 who advised me to appoint you.’ My father retorted, ‘Why didn’t he suggest one of his cousins for the job?’ The governor held firm, however, and Father accepted the appointment.

Around that time, the ruler of Egypt, Said Pasha (1854–63) paid a visit to the province of Minya. When he told the governor, Mustafa Bey, that he wished to visit one of the notables of the province, Mustafa Bey suggested either my father or al-Sharii Pasha. Because Father’s village was closer, the ruler decided to visit him first. While he sat with Father in the kiosk in t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- About the Authors

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of photographs

- Preface

- Chronology

- Introduction

- Part One: The Family

- Part Two: Childhood in the Harem 1884–92

- Part Three: A Separate Life 1892–1900

- Part Four: A Wife in the Harem 1900–18

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Appendix

- Glossary

- Index