![]()

CHAPTER 1

Delaware County Before and at the Time of the Murder

William Penn understood persecution. Even his father opposed his Quaker faith. But when Penn stepped off the ship Welcome, he was met by people of similar convictions who had heard of his “great experiment” and wanted to be part of it.

Penn’s settlement was preceded by the Dutch, the Swedes and, of course, the original Native American inhabitants who numbered as many as 6,000. Like the Puritans before them, Quakers cast their eyes toward America and viewed it as a place of refuge. By the 1670s, Friends already established in the new country were writing home with news of the peaceful Indians, fertile fields and abundant food. This promise of serenity and wholesomeness urged a large emigration of Quakers, willing to risk anything to escape the unreasonable persecution of their English countrymen to settle in what would become New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Delaware. An estimated 1,400 Quakers awaited Penn’s arrival.

The ship Welcome left England on September 1, 1682. Two months later, on October 27, Penn made landfall just off the coast of New Castle in what is today the state of Delaware. With him arrived some seventy immigrants. Nearly a third of the passengers died of smallpox on the journey. Two days later, Penn stopped at Upland before proceeding farther north toward Philadelphia. He entered into his labors as proprietor with characteristic vigor and immediately created Pennsylvania’s three original counties: Bucks, Philadelphia and Chester. A portion of Chester, including the town by the same name, became Delaware County in 1789.

William Penn’s “Great Law” regulating his first three counties was the basis on which the entire commonwealth government eventually operated. Religious liberty was guaranteed to all. Only indentured servants and vagrants were denied the right to vote. Unlike in England, where the complexity of the law made it difficult for the average person to understand it let alone defend himself, Penn attempted to simplify the legal process for the inhabitants of his new province. The death penalty was abolished for all crimes except willful murder and treason. In his effort to create a perfectly moral state, drunkenness was punishable by fine or imprisonment, as were swearing, lotteries and other “evil” sports and games.

Penn envisioned himself very much as a father to the people of his province. In a proclamation distributed prior to his arrival, he told them:

It hath pleased God in His providence to cast you within my lot and care. It is a business that though I never undertook it before, yet God hath given me an understanding of my duty, and an honest mind to do it uprightly. I hope you will not be troubled at your change and the king’s choice, for you are now fixed at the mercy of no governor that comes to make his fortune great; you shall be governed by laws of your own making, and live a free and, if you will, a sober and industrious people. I shall not usurp the right of any, or oppress his person.

Twenty-three vessels arrived in 1682. Most of these immigrants were financially secure. They brought their own furniture, provisions, tools and building supplies, allowing immediate construction of their new homes. But the settlers did not just travel with material goods. The religious tenets and hierarchies established in the old country were reestablished in the new land. Churches performed many of the functions government would later assume: education, relief for the poor and arbitration of neighbors’ disputes.

In 1683, some fifty more ships filled with immigrants arrived, most of them Welsh Quakers and Germans whom William Penn had personally invited while sailing the Rhine River. While early German immigrants were Friends, later waves were composed mainly of Mennonites and followers of other faiths. They arrived in the Delaware County region in large numbers and would eventually become a predominant presence in the formerly Quaker landscape.

William Penn’s relationship with the Native Americans from whom he purchased land was based on the Quaker principles of fairness and honesty. “Do not abuse them,” he said, “but let them have but justice and you win them.” While settlers in other states were fighting protracted and bloody battles with native tribes, Pennsylvanians—most of them pacifists and without weaponry—enjoyed peace, lucrative trade and strong personal friendships. So protective was Penn of the Native Americans with whom he’d negotiated land deals that he made it illegal to sell them alcohol or offer strong drink during the treaty-negotiation process, tactics less scrupulous white bargainers had used to their favor.

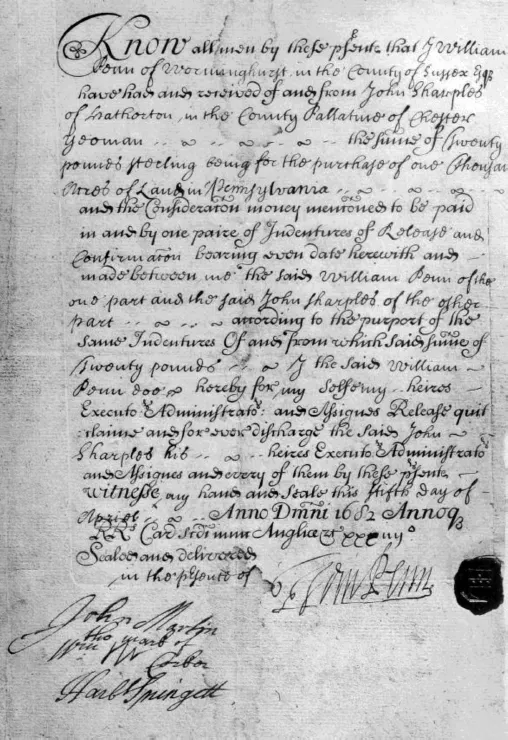

A 1682 deed of sale from William Penn to John Sharpless for land in Pennsylvania. Image from Genealogy of the Sharpless Family.

Sadly, while Quakers held Native Americans in reverence, they were not—at least in earliest times—averse to the bondage of African Americans. The practice of importing slaves was common from the first days of the province through the early 1700s, when large numbers of Scots-Irish and a second huge wave of German immigrants willingly accepted contracts for as many as seventeen years of indentured servitude in exchange for the opportunity to come to America.

Six decades after Delaware County’s inception, 5,280 residents (about a quarter of those answering the question of religion) claimed membership in the Quaker sect. Methodists (primarily German) were quickly gaining a foothold in the county and, with 4,360 members, were the second-largest religious grouping. A much smaller religious sect, those identifying themselves as African Methodists, had only four congregations to the Quakers’ sixteen. The African Methodist Bethel Church was organized in the town of Chester on a lot purchased for one dollar from John M. Broomall—close friend to the Sharpless family and a man who figured prominently in Delaware County law and politics.

At the time of the 1840 census, a divided nation and bloody civil rebellion was an unfathomable future horror. Pennsylvania’s Quaker leadership had determined more than a century prior that ownership of slaves would preclude members from attaining governance roles. The state legislature, likewise early in its opposition to slavery, passed an edict in 1780 calling for gradual emancipation—an insufficient measure in retrospect but one that preceded the efforts of its neighbors. Under the bill, all children of African Americans born after passage of the law would become free at age twenty-one.

The Civil War devastated the South, and recovery took years. For the North, the postwar period came to be known as America’s Gilded Age. Tycoons like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller were role models for aspiring millionaires. Trains, both utilitarian and elegant, raced along rails stretching from one coast to the other. The telephone was invented, and the typewriter became the high-tech office tool. The United States was a manufacturing goliath.

The financial crash of 1873 abruptly interrupted this period of prosperity. It started in Philadelphia with the closure of the banking house J. Cooke & Company. Thought to be impregnable, the September 18 run on this esteemed institution set off a national panic. Cooke was invested heavily in the railroads. Overexpansion resulted in the collapse of the bank’s credit rating. Account holders demanded withdrawal of their money. Runs on other Philadelphia banks ensued, with the madness soon infecting the entire country. Companies closed, factories ceased production, unemployment skyrocketed and Americans of all economic circumstances suffered a six-year retraction that, until overshadowed by the collapse in 1929, was called the “Great Depression.”

By the 1880s, economic recovery was complete and the panic forgotten. Delaware County, like the state and nation at large, was enjoying the second industrial revolution. The Chester Times reported that the most exciting events of 1884 were an earthquake and some particularly rancorous political campaigning. Otherwise, people and businesses went about their days in customary fashion.

Expectations for 1885 were bright—and why shouldn’t they be? Situated on the Delaware River just southwest of Philadelphia, the residents of Delaware County had survived epidemics, natural disasters, financial loss, harsh Pennsylvania winters and steamy, mosquito-ridden summers. At seventy-five thousand, the population was eight-fold what it had been at the time of the county’s formation.

Thanks in large part to the Quaker schools, county children were well educated. Friends believed education led to the knowledge required to aid one’s fellow man. But good schools were not the only advantage enjoyed by the people of Delaware County in the late nineteenth century. Its proximity to a major waterway made the area an attractive place to live and conduct business. The waterfront was a lucrative shipbuilding and industrial mecca. Resort hotels sprang up to accommodate the annual influx of urban money. Media’s Idlewild Hotel boasted a bowling alley, a nine-hole golf course and a wooden boardwalk leading from the train station to the rear veranda—presumably so its esteemed guests never need soil their expensive shoes on the dusty streets. A stocked pond provided live trout, and a dairy herd supplied fresh milk to the “old Philadelphia families” who arrived at the hotel on the first of May and departed the first of November. Successful business owners, honored military men, great legal minds and important medical pioneers all made permanent homes in the county, adding to its upscale reputation and appeal.

With the Civil War a generation in the past and the county’s economy roaring, surely 1885 would be another predictable, peaceful and prosperous year.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

The Sharpless Family

Some families possess an innate understanding of their place in history. The fact that they are, and forever will be, a unique aggregate sharing a common bloodline is celebrated from the time of their first family gathering. Early generations of the Sharpless family were like this—preserving family treasures, commissioning written histories and reuniting far-flung cousins from around the country and world.

The first immigrants, John and Jane Sharpless, arrived in Pennsylvania on the ship Friendship on August 14, 1682—two months before William Penn’s landing. Six of their children arrived with them. The seventh, son Thomas, died on the long voyage from their homeland in England.

To describe these transatlantic trips as arduous is like saying the Revolutionary War was a prolonged skirmish. In a feeble attempt to outwit weather and sea, most ships left England in late summer with the goal of arriving on our eastern coast in early fall. Voyages lasted anywhere from sixty to ninety days. “Ship fever” ran rampant—the seafarer’s equivalent of the claustrophobia and restlessness resulting from being pent up in one place for too long. Prevailing winds died suddenly and hid for days. Ships crashed into rocks within sight of their intended ports. Sickness spread as easily as breathing. Survival of every person listed on the passenger manifest was rare. And while some travelers were buried at sea, babies birthed en route took their place in the New World. Knowing these odds, the Sharpless family left the comfortable life enjoyed in their country of birth to come to a place they had never seen to start over—figuratively and literally—from the foundation up.

Sharples Hall in Lancashire, England—the ancestral home of the Sharpless family of Delaware County, Pennsylvania. Image from Genealogy of the Sharpless Family.

The family hailed from Sharples in Lancashire, England. Lancashire, located toward the northwestern corner of the country, was founded in the twelfth century. Mention of Sharples is found in very early thirteenth-century records. It was named after a family who once made their home on Sharples Hill, although the last known representative of that clan died in 1816. The ancestral home was beautifully crafted, the archetypal English manor that springs to mind whenever such homes are imagined today. Leaving this place took unimaginable courage.

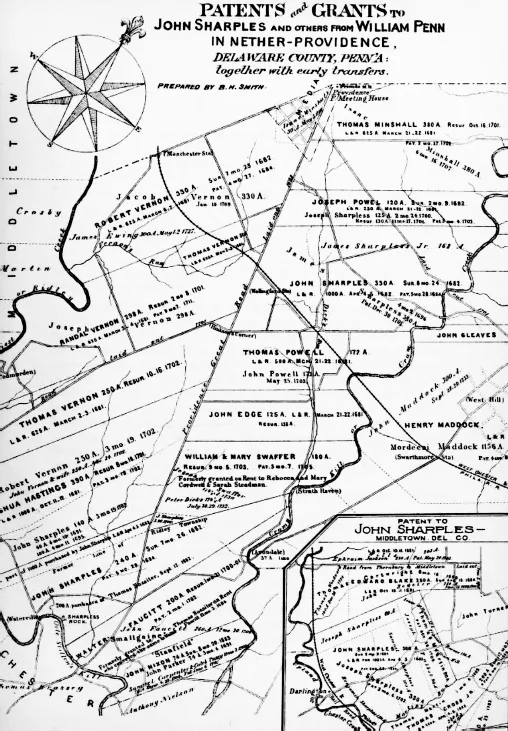

The family patented three parcels of land in the part of Chester County that would be taken to create Delaware County. These three parcels totaled 870 acres.

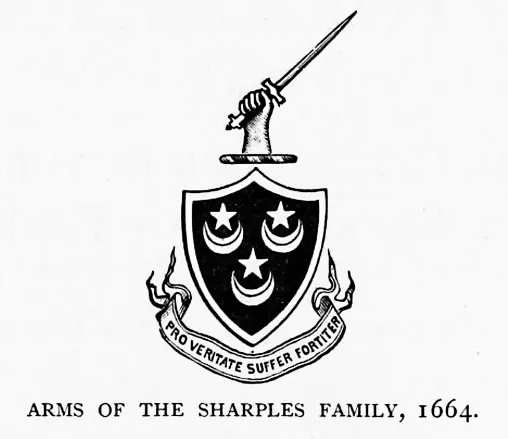

Legend has it that after the family settled on their large homestead near Media, they made a ceremonial sacrifice. The family coat of arms—which bears a Latin inscription meaning “suffer bravely for truth”—was buried near a large exposed rock. Onto its face the immigrant John Sharpless carved “1682,” along with his initials. The first Sharpless home, a log cabin of sorts built from the surrounding trees, utilized this rock as part of its foundation.

The Sharpless family coat of arms bearing the Latin inscription Pro Veritate Suffer Fortiter, meaning “suffer bravely for truth.” Image from Genealogy of the Sharpless Family.

From their earliest arrival in what was then Ridley Township, the Sharpless family exercised influence. When rugged, rocky paths made transportation too difficult, it was the Sharpless family who helped petition for new roads. When in 1753 it became “a very Great Inconvenience to meet at the White Horse tavern” to discuss township affairs, the Sharpless family and others successfully lobbied to make Ridley part of the more easily traversable Nether Providence Township.

Four Sharpless men paid taxes to Nether Providence in the 1820s, one of them being John Sharpless Sr., the father of our subject. Between them they owned nearly three hundred acres of township land, the rest of the original patents having been sold off to neighbors and extended family members. These men also owned a fulling mill, gristmill, sawmill, cotton factory, smith shop and blade mill—enterprises constituting a large portion of the township’s economy.

A Nether Providence Township map showing William Penn’s patent and grants to John Sharpless and others. Image from Genealogy of the Sharpless Family.

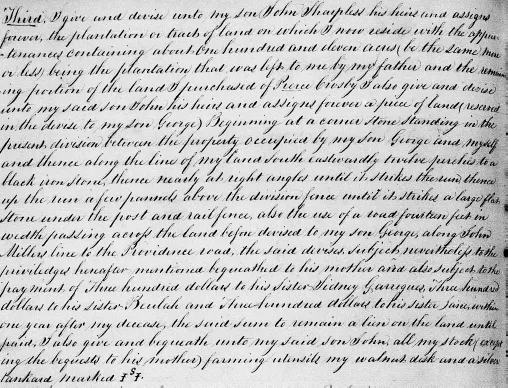

An excerpt from the original will of John Sharpless Sr. showing his bequests to son John Sharpless Jr., the subject of this book. Image created by author from Delaware County court records.

The John Sharpless who is the subject of this book was born in Nether Providence Township in 1824, a sixth-generation descendant of the immigrant. To distinguish himself from his father (and other family members of the same name), John used the suffix “Junior.” Like generations before, his family lived on the acreage first settled by John and Jane Sharpless. It was not a secret that John Sharpless Jr.’s family was wealthy and that this wealth was expected to pass to him and his siblings.

John Sharpless Sr. was born in 1778 while the American Revolution raged. This conflict brought out divisions among Friends. While some Quakers felt inclined to support the fight for liberty, if only by means of supplies and provisions, many others felt such attitudes compromised Friends’ pacifist ideals. There are no known records documenting Sharpless family aid to the Revolutionary effort.

John Sr. was a respected member of the Quaker community and in 1816 became an overseer of the Chester Meeting. At his death in 1854, six of his ten children to wife Ruth Martin survived him. He willed his 111-acre homestead to John Jr. Also bestowed to John Jr. was a silver tankard that family lore suggests was brought to America by the original immigrant and lovingly protected by each succeeding generation. To son George, John Sr. gave land that had once been part of the S...