eBook - ePub

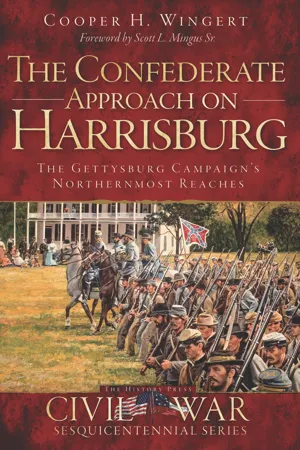

The Confederate Approach on Harrisburg

The Gettysburg Campaign's Northernmost Reaches

- 227 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Confederate Approach on Harrisburg

The Gettysburg Campaign's Northernmost Reaches

About this book

The little-known story of how Southern forces came close to invading the capital of Pennsylvania—includes photos.

In June 1863, Harrisburg braced for an invasion. The Confederate troops of Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell steadily moved toward the Pennsylvania capital. Capturing Carlisle en route, Ewell sent forth a brigade of cavalry under Brigadier Gen. Albert Gallatin Jenkins. After occupying Mechanicsburg for two days, Jenkins's troops skirmished with Union militia near Harrisburg. Jenkins then reported back to Ewell that Harrisburg was vulnerable.

Ewell, however, received orders from army commander Robert E. Lee to concentrate southward—toward Gettysburg—immediately. Left in front of Harrisburg, Jenkins had to fight his way out at the Battle of Sporting Hill. The following day, Jeb Stuart's Confederate cavalry made its way to Carlisle and began the infamous shelling of its Union defenders and civilian population.

Running out of ammunition and finally making contact with Lee, Stuart also retired south toward Gettysburg. In this enlightening history, author Cooper H. Wingert traces the Confederates to the gates of Harrisburg in these northernmost actions of the Gettysburg Campaign.

In June 1863, Harrisburg braced for an invasion. The Confederate troops of Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell steadily moved toward the Pennsylvania capital. Capturing Carlisle en route, Ewell sent forth a brigade of cavalry under Brigadier Gen. Albert Gallatin Jenkins. After occupying Mechanicsburg for two days, Jenkins's troops skirmished with Union militia near Harrisburg. Jenkins then reported back to Ewell that Harrisburg was vulnerable.

Ewell, however, received orders from army commander Robert E. Lee to concentrate southward—toward Gettysburg—immediately. Left in front of Harrisburg, Jenkins had to fight his way out at the Battle of Sporting Hill. The following day, Jeb Stuart's Confederate cavalry made its way to Carlisle and began the infamous shelling of its Union defenders and civilian population.

Running out of ammunition and finally making contact with Lee, Stuart also retired south toward Gettysburg. In this enlightening history, author Cooper H. Wingert traces the Confederates to the gates of Harrisburg in these northernmost actions of the Gettysburg Campaign.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Confederate Approach on Harrisburg by Cooper H. Wingert in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Harrisburg in Distress

It was pitch dark as many of the senior commanders of the Federal Army of the Potomac huddled in council past midnight on May 4, 1863. Their topic of discussion would have been inconceivable to anyone in the group—or for that matter any soldier in the large Northern army—a mere week ago. Then, in the last days of April, the Army of the Potomac boasted over 130,000 men, an imposing size compared to the meager Southern forces opposing them. Nearly all were extremely confident in their ability to deal with Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. However, the sheer thickness of the so-called Wilderness—the dense, overgrown woods that enveloped the area west of Fredericksburg, Virginia, and south of the Rappahannock and Rapidan Rivers—seemed to clog the thought process of army commander Major General Joseph O. Hooker as much as it did the pace of his army’s march.

Hooker, who had frequently boasted of his upcoming offensive, soon stalled his progress around the Chancellor house when a bold counteroffensive by Lee and legendary corps commander Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson stunned him. The battle took a turn for the worse for “Fighting Joe” when Lee dispatched Jackson as a flanking column. Stonewall’s veterans reaped havoc on Hooker’s bewildered army, whose right flank soon collapsed. Hooker’s confidence and grand plans of a marvelous victory faded away before him.

So brought Hooker and five of the army’s seven corps commanders to this unwelcome meeting. The befuddled Hooker thought of retreat and only that. “It was seen by the most casual observer that he had made up his mind to retreat,” later opined Second Corps commander Major General Darius N. Couch. “We were left by ourselves to consult,” recollected Couch. A vote was taken, resulting three to two in favor of offensive operations. Hooker sauntered back to the tent and, after being informed of the vote, announced that “he should take upon himself the responsibility of retiring the army to the other side of the river.” That was only another step in the beginning of the end for Fighting Joe’s tenure at the helm of the Army of the Potomac. With that move, he did little to soothe his subordinates’ anger.1 As Fighting Joe lost the tenacity garnered him by his sobriquet, Robert E. Lee basked in it.

HARRISBURG

Laid out in 1785 and incorporated as a borough in 1791, Harrisburg became Pennsylvania’s capital in 1812. The town’s founder, John Harris Jr., boasted to one traveler in 1788 that “three years ago there was but one house built,” and soon it had become a rapidly growing town on the eastern banks of the Susquehanna River. “Harrisburg is most picturesquely situated,” raved one observer.2 “There are few cities which in proportion have such a large number of merchants keeping retail stores,” described eighteenth-century traveler Theophile Cazenove.

The lands watered by the Susquehanna are so excellent, that settlements are made hourly, and the farmers are generally supplied from here; also from here comes…products, that go down the river in boats…There is here a printing-plant, where an English newspaper is…published every Monday and costs 2 dollars a year for subscription; a school, where I saw about 60 children learning from only one teacher, reading writing, arithmetic, grammar, etc…A German church, where Lutherans and German Presbyterians have alternate services…The county-jail had one prisoner, a thief, condemned to 2 years imprisonment, and 3 noisy negroes…They are making the [new courthouse] building so large with the idea that the Pennsylvania legislature will hold its meetings here.3

In 1794, during the Whiskey Rebellion, President George Washington visited the then-nine-year-old, rather insignificant town. “The Susquehanna at this place abounds in the Rockfish of 12 or 15 inches in length, and a fish which they call Salmon,” Washington penned in his diary. After spending the night in Harrisburg, on October 4 he forded the Susquehanna, passing over Forster’s Island, now known as City Island, in the middle of the river.4

“The river from the [capitol] dome is the most beautiful I think I ever saw,” noted another spectator. “The river studded with Islands covered with rich foliage stretches away as far as the eye can reach above and below the town while the two splendid, bridges, almost, or quite a mile long, add very much to the picturesqueness of the scene.”5

One of these two “splendid” bridges spanning the Susquehanna was the Camelback Bridge, a roughly mile-long covered bridge. In the early months of 1812, the Harrisburg Bridge Company, composed of many of the city’s most prominent and wealthy persons, formed with the ingenious idea of establishing a toll bridge for pedestrians and wagons to cross the Susquehanna. The company contacted bridge builder Theodore Burr, who responded, “I am…more than willing to undertake your Bridge, and can build you one, on the most improved plan which combines in itself conveniences, strength, Durability and eligance [sic]; for $175,000 every way complete and properly secured from the weather[.]”6

Burr soon started work. On May 27, 1814, a sad reminder occurred of the dangers of bridging the mile-wide Susquehanna. Four men fell—one injured “pretty bad,” breaking his leg—while three others suffered minor injuries, though Burr felt confident that they “will be able to work again in a short time[.]”7 In 1817, workers completed the bridge, which opened up a new line of traffic across the Susquehanna. The idea that had begun five years earlier had proved an extremely profitable venture.

It was not long before the Harrisburg Bridge Company had to compete with the neighboring Cumberland Valley Railroad (CVRR) Bridge, which initially allowed foot and horse traffic as well as locomotives. In September 1847, the Harrisburg Bridge Company accustomed its tolls to those of the CVRR Bridge:

Pheaton Pleasure Carriage or Sleigh drawn by;

One horse or mule, 25 cents.

Two horses or mules, 50 cents.

Four horses or mules, 75 cents.

Loaded wagon or Sled Carriage or Sleigh drawn by;

One horse or mule, 20 cents

Two horses, mules or oxen, 60 cents

Every additional horse mule or ox, 5 cents

Each cord of firewood, 62½ cents

Single Horse and Rider, 15 cents

Horse, mule, or donkey without a rider, 8 cents

Foot passenger, 3 cents.8

However, in 1850, word came that Robert Wilson, toll collector for the CVRR Bridge, allowed cattle and other stock to pass for a lesser toll than the rates the two companies had agreed upon in 1847. Naturally, the Camelback lost substantial business. The end result proved extremely profitable for both companies. On November 6, 1850, an agreement was signed that the CVRR would be paid quarterly an annual sum of $5,000 for the next ten years to ban all pedestrian, stock and wheeled traffic from its bridge and demote itself entirely to locomotive travel. Both companies enjoyed this transaction so much that it extended long past the original expiration date of 1860.9

DEFENDING THE CAPITAL

Harrisburg, with a population of fourteen thousand in the 1860 census, had certainly seen its share of war by the early summer of 1863. Three days after Fort Sumter had surrendered and the war broke out in mid-April 1861, Camp Curtin was established. It soon became the largest training camp in the North.

In the late spring of 1863, General Robert E. Lee and his Confederate Army of Northern Virginia were again plotting an invasion into the Dutch farm fields of southern Pennsylvania after he had been stalled at Antietam the previous fall. His goals included relieving Virginia of the heavy burden of being the eastern theater’s main fighting ground, replenishing his army’s subsistence with foods at the expense of Maryland and Pennsylvania farms, drawing Federal attention from other sectors and targeting Harrisburg, the capture of which had the potential of greatly embarrassing Federal war efforts. A combination of the above could give Lee a successful campaign and push forth peace talks for the end of the war and ultimately the Confederacy’s independence.

Harrisburg was among the most promising of these options. It was, of course, a Northern capital, the capture of which would give the Rebels a major morale boost and an outside chance of foreign recognition. Camp Curtin was located in Harrisburg, which, if captured, would cut off a major flow of Federal reinforcements to the Northern armies engaged in the field. Lastly were the dozens of roads, bridges and railroads emanating from the city, several of which led to Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington, three cities that would have, if captured or substantially threatened, severely damaged any leverage President Abraham Lincoln still held to continue the war. “If Harrisburg comes within your means, capture it,” Lee wrote to Second Corps commander Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell on June 22.10 Capturing or threatening Harrisburg could significantly help Lee accomplish his strategic goals.

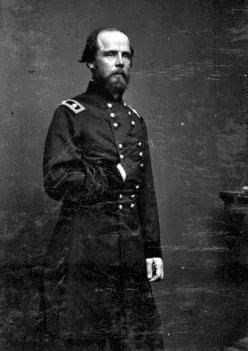

To protect Pennsylvania’s capital, the Federal War Department assigned Major General Darius Nash Couch, a West Pointer and former corps commander in the Army of the Potomac. Born in Putnam County, New York, on July 23, 1822, he was raised with a common school education. He graduated from the highly noted West Point class of 1846 with George McClellan and “Stonewall” Jackson, the latter Couch’s roommate. Couch was brevetted for gallantry and meritorious conduct in the Mexican War. In 1855, he resigned his commission to enter the copper fabricating business of his wife’s family in Taunton, Massachusetts.

When war erupted in 1861, he became colonel of the 7th Massachusetts. Couch enjoyed rapid promotion when former classmate George McClellan took command. The New York native proved to be a steady and consistent commander as he led a division of the Fourth Corps in the Peninsular Campaign. In July 1862, illness prompted Couch to tender his resignation to McClellan, who refused it and instead promoted him to major general. Engaged at Antietam as a divisional commander, Couch commanded the Second Corps at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. He expressed disgust at the behavior of then–army commander Joe Hooker, who was largely (and rightly) blamed for the disaster at Chancellorsville. Couch reportedly “told Mr[.] Lincoln that he had served through two disastrous campaigns rendered so by the incompetency of the commanders as he had no faith in any improvement, he requested to be separated[.]” By one account, Lincoln even tendered command of the army to Couch, though he declined it.11

Major General Darius N. Couch, commander of the Department of the Susquehanna. Courtesy of the MOLLUS-MASS Collection, U.S. Army Military History Institute.

On June 9, an order establishing two different departments was drafted; however, evident errors in the order required another edited order, which was released from the War Department the next day. Brigadier General William T.H. Brooks assumed command of the Department of the Monongahela, which embraced those parts of Pennsylvania west of Johnstown and the Laurel Hills, including several counties in West Virginia and Ohio, with headquarters in Pittsburgh. General Couch was assigned to the command of the Department of the Susquehanna, which consisted of the land east of Johnstown and the Laurel Hills, headquartered in Harrisburg.12

On June 11, Couch left Washington and entrained for Harrisburg. When he arrived the next evening, he met with Pennsylvania’s Republican governor, Andrew Gregg Curtin, and his council of military advisors.13 All understood the first task at hand was to raise volunteers. Couch proposed a proclamation that began by explaining the emergency. The document went on to detail that “when not required for active service to defend the department, they will be returned to their homes, subject to the call of the commanding general.” Couch’s order also incorporated a bounty system using the only enticing item he had because the department was desolate of funds: rank. It stated that any person who brought forty or more men would be commissioned a captain, twenty-five or more men a first lieutenant and fifteen or more men a second lieutenant.14 Instead, many showed up eager to be officers but with no men accompanying them.

On June 12, Curtin issued the first of three proclamations, confirming the rumors of a Rebel invasion and urging citizens to respond to either Couch’s or Brooks’s General Orders for troops. “The importance of immediately raising a sufficient force for the defense of the State cannot be overrated,” Curtin declared.15

Colonel Thomas A. Scott, aide and advisor to Curtin, recognized several flaws in Couch’s call (which Curtin’s June 12 proclamation advocated), namely its appeal to ordinary Pennsylvanians. As Scott’s biographer noted, “There was a serious lack of definiteness about the whole arrangement.” Volunteers were informed that they would be treated like Regulars while in the field and returned home when “not required for active service.” Their terms of ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Harrisburg in Distress

- 2. The Defenses of Harrisburg

- 3. Southern Invaders

- 4. Carlisle Falls

- 5. Preparations at Oyster’s Point

- 6. Jenkins Captures Mechanicsburg

- 7. The Skirmish of Oyster’s Point Begins

- 8. Spies, Scouts and Traitors

- 9. Jenkins Reconnoiters Harrisburg

- 10. The Battle of Sporting Hill

- 11. The Shelling of Carlisle

- 12. After Carlisle

- Epilogue

- Appendix A. Casualties during the Shelling of Carlisle

- Appendix B. The Death of Private Charles Colliday at Carlisle

- Abbreviations

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author