- 129 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

An inside look at the history and traditions behind this New England delicacy.

Since the first recorded lobster catch in 1605, the Maine lobster fishery has grown into a multibillion-dollar force. In this book, Cathy Billings of the University of Maine Lobster Institute embarks on a journey from trap to plate, introducing readers to lobstermen, boat builders, bait dealers, marine suppliers, and the expansive industry that revolves around the fishery.

Maine lobster families extend for generations back, and strides in sustainability have been a hallmark of the Maine fishery throughout the centuries—from the time lobstermen themselves introduced conservation measures in the mid-1800s. Today, Maine's lobster fishery is a model of a co-managed, sustainable fishery. The people who work Maine's lobster fishery have developed a coastal economy with an international influence and deep history, and this book takes you behind the scenes.

Since the first recorded lobster catch in 1605, the Maine lobster fishery has grown into a multibillion-dollar force. In this book, Cathy Billings of the University of Maine Lobster Institute embarks on a journey from trap to plate, introducing readers to lobstermen, boat builders, bait dealers, marine suppliers, and the expansive industry that revolves around the fishery.

Maine lobster families extend for generations back, and strides in sustainability have been a hallmark of the Maine fishery throughout the centuries—from the time lobstermen themselves introduced conservation measures in the mid-1800s. Today, Maine's lobster fishery is a model of a co-managed, sustainable fishery. The people who work Maine's lobster fishery have developed a coastal economy with an international influence and deep history, and this book takes you behind the scenes.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Maine Lobster Industry by Cathy Billings in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Sustainable Development. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

SETTING THE SCENE

THE FIRST RECORDED LOBSTER CATCH

The Archangel, captained by George Weymouth, set sail from Ratcliffe, England, on March 5, 1605. It was seventy-three long days before the company of twenty-nine men spied land off the coast of what is now the state of Maine. They first made landfall on Monhegan Island on Friday, May 17, and here they replenished their spent supplies of dry wood and fresh water. Two days later, they found themselves off the coast of Maine’s St. George’s Islands.

James Rosier accompanied Captain Weymouth and kept a written account of his observations. Of the St. George’s Islands, he wrote, in the old English of the day, that they had “found a conuenient Harbour, which it pleased God to send vs, farre beyond our expectation, in a safe birth defended from all windes, in an excellent depth of water for ships of any burthen.”1 Here they took respite from their days at sea. Fish was bountiful in Maine’s pristine waters, and some of the men set out each day in the vessel’s shallop (a small, open boat fitted with oars and sails for use in shallow waters) to catch cod, haddock and other small fish.

It was on Tuesday, May 21, that Rosier reported, “…Towards night we drew with a small net of twenty fathoms very nigh the shore: we got about thirty very good and great Lobsters, many Rockfish, some Plaise, and other small fishes, and fishes called Lumpes, verie pleasant to the taste: and we generally obserued, that all the fish, of what kinde soeuer we tooke, were well fed, fat, and sweet in taste.”2

This marked the first recorded catch of the American lobster, Homarus americanus. While it is said that the catch by Captain Weymouth’s crew was the first recorded lobster catch, it is important to note that Maine’s Native Americans were most likely catching lobsters for many years before the Archangel found their shores. Indeed, Rosier noted the sailors found evidence of camp fires, egg shells, fish bones and animal bones when they first came ashore.3 This is further validated by English explorer Thomas Morton, who in 1622 recorded the following observation of lobsters’ role in Native American feasts: “This being knowne, they shall passe for a commodity to the inhabitants; for the Savages will meete 500 or 1,000 at a place where Lobsters come in with the tyde, to eate, and save dried for store; abiding in that place, feasting and sporting, a moneth or 6 weekes together.”4

It has been written that Native Americans used lobsters to fertilize their crops and bait their fishing hooks. They did also eat them, reportedly preparing them by placing them over heated rocks and covering them with seaweed. According to tradition, this cooking method inspired the classic New England clambake.

The crustacean was said to have been so plentiful in those early colonial years that all one had to do was wade into the shallows, reach down and pick up lobsters from the bottom. It is my theory that it was the Native American women who were actually the first to catch lobsters in Maine, by hand or with dip nets. This is because it was more a chore of gathering or harvesting, which was left to the women, rather than fishing or hunting, which were jobs for the men.

Though it is hard to believe in this day and age, when you might pay thirty-four dollars or more at a New York restaurant for a steamed lobster, that due to their great abundance in colonial times, lobsters came to be known as the food of paupers. They were so plentiful and so common that legend has it that indentured servants would even have it written into their contracts that they could not be served lobster more than three times per week.5

As the colonies became more settled, trade and commerce grew. Lobster could be found in most markets reaching from Maine to New York. Markets did not extend any farther in these early days of American history. Unlike most other fish or meats, lobster must be shipped and cooked as a live animal. Outside of water and absent refrigeration, a lobster will perish within a day. Spoilage will spread through uncooked dead lobsters fairly quickly, making them unsafe to eat. This challenge of keeping lobsters alive on their way to market severely limited shipping in colonial days, and thus the markets for lobster stayed rather local for decades.

HOMARUS AMERICANUS: THE CENTERPIECE OF THE INDUSTRY

The centerpiece of what was to become a multibillion-dollar industry is Homarus americanus, the American lobster. The American lobster is a cold-water, benthic crustacean—meaning that they are shellfish that dwell on the bottom of the icy oceans ranging from Virginia up through the Canadian Maritimes. There is no other place on earth where you can find Homarus americanus. While lobsters can be found in the United States as far south as Virginia, today’s commercial fishery really starts in Rhode Island. It runs through the coastal states of New England, with Maine having the most abundant stocks.

Lobsters are aquatic arthropods of the class crustacea. As such, they have segmented bodies, chitinous exoskeletons (a hard outer shell with no internal skeleton or bones) and paired, jointed limbs.

Lobsters are classified in the phylum arthropoda (which also includes shrimp, crabs, barnacles and insects). The word arthropoda comes from the Latin word “arthro,” meaning jointed, and the Greek word “poda,” meaning foot. This nomenclature refers to the lobster’s jointed appendage (claws and walking legs). Lobsters are also decapods, deca being Greek for “ten.” This term refers to the lobster’s ten legs (five pairs), including eight walking legs (pereiopods) and two major claws.

In laymen’s terms, the largest claw is known as the “crusher claw.” It is used to literally crush prey such as other shellfish like mussels or clams. The smaller of the two claws, commonly called the “pincher claw” or “ripper claw,” is pointed and has sharp, jagged edges used for tearing food apart. It is these claws that set Homarus americanus apart from most other types of commercially fished lobsters (notably the spiny lobster, Panulirus argus, which lives in warmer waters). Many find that the claws and knuckles (appendages leading to the claws) of the American lobster contain some of the sweetest, most tender meat.

The American lobster, showing the large crusher claw, smaller ripper claw, four pair of walking legs, the carapace and the tail.

Juvenile lobsters held in a fisherman’s gloved hands. Courtesy of Bob Bayer.

As a close relative of insects, lobsters have frequently been called “bugs” by fishermen. Like insects, lobsters are invertebrate arthropods. As noted, they have a hard outer “skeleton” and no backbone or spinal column. Both have very primitive nervous systems, and neither insects nor lobsters have brains. Furthermore, lobsters and other invertebrates have only about 100,000 neurons, while humans have over 100 billion.6

Lobsters grow from eggs that are carried within a female lobster for about nine months and then are extruded and carried on the underside of a lobster’s tail for about another nine months, held in place by a glue-like substance. These eggs are no bigger than the size of a pinhead—approximately one-sixteenth of an inch. When the eggs hatch, they are released from the tail as Stage I larvae. They are so light that for the first two weeks or so, they float in the water column and are very susceptible to predators. They will quickly grow by molting through three stages. After the fourth molt, the few that survive will settle to the bottom and look for hiding places in rocks, grassy areas, etc. Now in the post-larval stage, they will progress through several more molt cycles before venturing out of hiding as juvenile lobsters. It takes five to seven years for a lobster to grow to the legal size for current-day harvesting. From every fifty thousand eggs, roughly only two lobsters are expected to survive to legal size.

During the molting process, a lobster will struggle out of its old shell while simultaneously absorbing water, which expands its body size. After molting, a lobster will eat voraciously, often devouring the shell it just shed. This replenishes lost calcium and hastens the hardening of the new shell. This molting, or shedding, occurs about twenty-five times in the first five to seven years until a juvenile reaches adulthood. Following this sequence, the lobster will weigh approximately one pound. After this time, the adult lobster might then molt only once per year or once every two years if an egg-bearing female. At this point, the lobster will increase about 15 percent in length and 40 percent in weight with each molt.

No one has yet found a way to determine the exact age of a lobster (though a promising new technique discovered in 2012 by Dr. Raouf Kilada at the University of New Brunswick is being validated as this is written). However, based on scientific knowledge of body size at age, the maximum age attained might approach one hundred years. Lobsters can grow three to five feet or more in overall body length.7

When one hears of lobsters being sold as either hard-shell or soft-shell, this is an indicator of at which point in the growth cycle the lobster was caught and sold. If caught leading up to a molt, the lobster will have a very hard shell. One may even notice that barnacles have attached themselves to the shell. These lobsters will have a higher meat yield by percent of body weight. If caught after a recent molt, the lobster will have a very soft shell and a lower meat yield due to the excess water taken in to aid in the process of shedding. There are several marketing implications related to whether a lobster is a hard-shell or soft-shell, which will be covered in chapter five.

As benthic creatures, lobsters function well in low-light conditions. In fact, they are most active at night, when, as a Mainer might say, “it is as dark as the inside of a pocket.” This is when these nocturnal creatures move about more readily in search of food and are most apt to enter the lobstermen’s baited traps.

CHAPTER 2

MAINE’S LOBSTERMEN—PROUD AND INDEPENDENT

While lobsters are the centerpiece of the industry, the lobstermen* are its heart and soul. The images of a lobsterman hauling his traps or displaying his catch are as iconic as the lobster itself. According to 2011 records, there were 5,961 commercial lobster-fishing licenses issued but only 4,345 lobstermen fishing in Maine. This leaves 1,616 latent or unused licenses issued. (Because it is difficult to reacquire a license, many fishermen are reluctant to give theirs up even if they aren’t fishing.) This number does not include those who fish as sternmen. There are three basic classifications of licenses. Class I is for a single owner/operator, Class II allows for one sternman and Class III allows for two sternmen.

Often a lobsterman’s day starts in the early morning hours before sunrise. Not too much of a lobsterman’s workday has changed over the centuries. While boats and equipment have certainly been modernized over the years, the routine of loading up with bait, heading out to traditional fishing grounds (first by sail and then by motor) and the routine of hauling traps, sorting the catch and re-baiting and resetting the traps has changed very little. Lobster fishing has remained primarily an inshore or near-shore fishery, with lobstermen setting out in the morning and coming back to the wharf by late afternoon. Maine law has always required that the owner of a lobster boat be the operator of the boat when fishing. Hence, it is still typically a one-man operation, though it can be two or three if the captain has sternmen to help with the baiting, banding of the claws and sorting. Sternmen do not carry their own licenses; rather, they fall under the captain’s license. They are not legally allowed to haul traps.

Catch of the day in 1938. Courtesy of Maine State Archives (via the Lobster Institute).

Lobstering entails a long day on the water, often ten to twelve hours or more. It is hard work out in the elements, with lots of time alone with one’s thoughts. Thus the persona of the rugged, solitary lobsterman was forged out of the realities of the work and the character of those who make their livings from the sea. Many of today’s Maine lobstermen were literally born for the job. Lobster fishing is a generational occupation, passed down first from father to son and now from father to son or daughter. Jason Joyce, who currently fishes out of Swan’s Island, is an eighth-generation lobsterman. In 2002, the Lobster Institute interviewed his grandfather, Robert Joyce, when he was in his eighties as part of its Oral History Program. Robert started lobstering at age eight with his father, Jason’s great-grandfather. He told of buying his first boat, a broken-down old skiff, for just one dollar and how proud he was to own his own vessel. It is this spirit of independence and pride that resonates with lobstermen from any region. When asked why they fished, other lobstermen interviewed by the Lobster Institute used words like “pride” and “independence” and phrases such as “…nothing like it,” “I wouldn’t do anything else” and “I love it.”

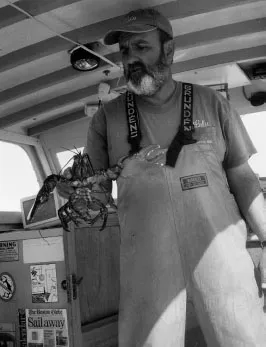

Captain John Nicolai, Winter Harbor, 2002.

I’ve lobstered all my life. I like it. As far as I’m concerned, the...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Introduction

- 1. Setting the Scene

- 2. Maine’s Lobstermen—Proud and Independent

- 3. Commercializing the Fishery

- 4. Gearing Up: Ancillary Businesses from Boats to Bait and Everything in Between

- 5. Accolades and Innovations Expand the Market

- 6. Getting from the Lobstermen’s Traps to Your Table: Who Is Handling Your Lobster?

- 7. Imports and Exports: The Canadian Connection

- 8. Sustainability: Conservation Before Conservation Was Cool

- 9. The Science of Lobsters: Researchers and Regulators

- 10. Marketing: A Taste of Maine

- 11. A Cultural Icon, a Community Heritage

- Notes

- Glossary

- About the Author