- 145 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"Clerici brings the race to life through . . . stories about every statue, landmark and portion of the course from its start in 1897 to its current incarnation" (

MetroWest Daily News).

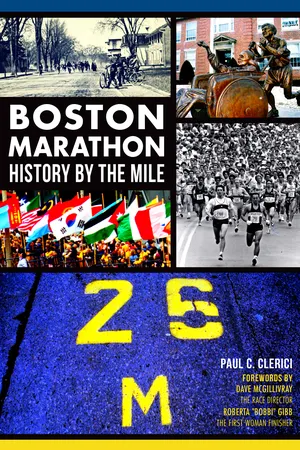

From Hopkinton to Boylston Street, the beloved 26.2 miles of the Boston Marathon mark historic moments and memories dating back to 1897. Town by town and step by step, follow author, journalist, and runner Paul C. Clerici as he goes deeper into each town and city along the route with firsthand descriptions of the course from the uphill climbs to the spirited sprints. Insightful anecdotes, from the naming of Heartbreak Hill to the incorporation of women runners, reveal meaningful racing heritage along the route. This comprehensive and unique journey also explores the stories behind notable landmarks, statues, and mile markers throughout the course. Woven into the course history is expert advice on how to run each leg of the race from renowned running coach Bill Squires. Whether you're a runner, spectator, or fan, Boston Marathon: History by the Mile has it all.

Includes photos!

From Hopkinton to Boylston Street, the beloved 26.2 miles of the Boston Marathon mark historic moments and memories dating back to 1897. Town by town and step by step, follow author, journalist, and runner Paul C. Clerici as he goes deeper into each town and city along the route with firsthand descriptions of the course from the uphill climbs to the spirited sprints. Insightful anecdotes, from the naming of Heartbreak Hill to the incorporation of women runners, reveal meaningful racing heritage along the route. This comprehensive and unique journey also explores the stories behind notable landmarks, statues, and mile markers throughout the course. Woven into the course history is expert advice on how to run each leg of the race from renowned running coach Bill Squires. Whether you're a runner, spectator, or fan, Boston Marathon: History by the Mile has it all.

Includes photos!

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Boston Marathon by Paul C. Clerici in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE BOSTON MARATHON

Like most great things in life, the Boston Marathon in its current form of nearly thirty thousand participants began humbly enough, with but fifteen men.

Thanks to a handful of members of the nine-year-old Boston Athletic Association (BAA) who competed in and witnessed the beautiful and otherworldly 1896 Modern Olympic Games in Athens, Greece, a spark was kindled that remained burning on their return home to America. Of the dozen men-only events at the Games, the marathon, in particular, so struck John Graham, the club’s coach/manager, that the seed was planted for what would become the grand dame of marathons.

The marathon is modeled after the accepted mythological story of ancient Greek soldier and messenger Pheidippides, who after a twenty-four-mile run from the battlegrounds of Marathon to the city of Athens in 490 BC to report the Athenian victory over the superior Persian forces, proclaimed, “Nenikekamen!” (“We have won!”) and instantly succumbed to a heroic death. Despite the historically and factually combined legend, the amalgamation survived to inspire millions. So much so that the word itself—marathon—has become known as more than a town in Greece; it is the pinnacle of duration, a far cry from its root origin as that of the flowered plant marathos (known as fennel) from that region of the world.

The first marathon footrace was held on March 10, 1896, in Greece and served as an ancient “qualifier” for the Modern Olympic Games marathon one month later, on April 10, 1896. Fittingly, the hometown Greeks won both races—Kharilaos Vasilakos in its debut and Spyridon Louis in the Olympics.

At the time in the United States, the BAA held its own multi-event competition called, simply enough, the BAA Games. From the Olympics, Graham had brought with him the embryonic idea and plans that would become the closing event of the BAA Games on April 19, 1897. According to the BAA, it was known in its infancy by several names, including the American Marathon, the BAA Road Race, and the BAA Marathon. And much like the 1896 Olympic Marathon was the second one held, so, too, was Boston’s in the United States. About six months prior to the BAA’s race, there had been a marathon that ran from Stamford, Connecticut, to the Knickerbocker Athletic Club at the Columbia Circle Oval in New York City. Interestingly, the victor of both U.S. marathons was John J. McDermott of New York.

To create the new course that approximated the Greek distance of about forty kilometers (24.85 miles), it was initially thought to follow in reverse order the route of Paul Revere’s famous Midnight Ride of April 18–19, 1775, to warn of the British soldiers who were on their way to arrest soon-to-be president of the Continental Congress John Hancock and future Massachusetts governor Samuel Adams. Revere’s ride, which took him from Charlestown to Boston (via the Charles River by boat) and then through Somerville (part of Charlestown back then), Medford (Mistick back then), and Lexington (where he was joined by fellow rider William Dawes via his separate route), was 13.25 miles.

Add to that distance Revere’s extra journey with Dawes (and then also with Dr. Samuel Prescott) of their own volition toward Concord, and the route increased 3.20 miles to the point where they were stopped by British soldiers in Lincoln and Revere was captured. In the end, the overall mileage was 16.45 miles, according to historian Charles Bahne and the Paul Revere House/Paul Revere Memorial Association. The BAA’s forefathers would have undoubtedly added on the necessary 8.00 or so miles, but 122 years of institutional memory loss and landscape and roadway changes appeared to have proved the original route too difficult to replicate.

Alternately, an approximate clockwise radius of the marathon distance to the north of Boston is just beyond the town of Lawrence and closes in on the New Hampshire state line. To the east is the Massachusetts Bay, to the south is just beyond the town of Mansfield and near the Rhode Island state line, and to the west is Ashland, through which traveled the Boston and Albany Railroad line. Home to such accommodating access, Ashland played host to the Boston Marathon for its first twenty-seven years and included three separate start locations. Hopkinton, the neighboring town to the west, has been the host town since 1924 and also included several different start lines.

With bicyclists leading the way, and a few waiting on the sidewalk at right, the field of the third annual Boston Marathon in 1899 makes its way up the dirt road of Main Street in Ashland. Courtesy Ashland Historical Society.

The distance of the Boston Marathon has fluctuated over the many decades, and not always by design—well, perhaps at times by design, but not always on purpose. The first twenty-seven runnings of the race landed in proximity to the 40K distance—in the vicinity of 24.0 to 25.0 miles, but most of them at 24.5 miles.

For the 1908 Games of the IV Olympiad in London, England, the marathon distance was extended to 26 miles and 385 yards (42.195 kilometers) to include a Windsor Castle start and an alternative track finish in front of the royal family box inside the Olympic White City Stadium.

While many marathoners’ anger since then has been justifiably aimed toward then-reigning King Edward VII, Queen Alexandra, and the Royal family for this additional footage, especially when struggling over the last couple miles, often forgotten is the fact that the 1908 Olympic Games were originally scheduled to be hosted by Rome but were relocated to the United Kingdom after the fatal 1906 Mount Vesuvius volcano eruption that decimated Naples (national focus turned from hosting the Games to rebuilding the city). Had those Olympic Games been held in Rome, who knows what distance the marathon would have become.

On the High Street bridge in Ashland, which was the second start-line location in Boston Marathon history, participants of the 1906 race gather before the tenth running. Courtesy Ashland Historical Society.

Thanks in large part to the nonprofit 26.2 Foundation (formerly the Hopkinton Athletic Association), the connection between the Olympic Marathon in Greece and the Boston Marathon can be seen in many ways.

The most constant nod is the laurel wreaths that are bestowed upon the male and female winners. The wreaths, which are fashioned from olive branches in the Greek town of Marathon, travel to Boston, where a ceremony takes place between the city’s Greek consulate general and Boston Marathon race officials. Replacing the previous chase-down approach at the finish line to place it on the (often still moving) winner of the old days is the current means of a more respectable laying of the wreath on the winner’s head at the finish-line awards podium. That ceremony also features the medal presentation and the playing of the winners’ national anthems, of which there are 140 different recordings at the ready.

In addition, special gold, silver, and bronze wreaths are also donated by Dimitri Kyriakides, the son of 1947 Boston Marathon winner Stylianos Kyriakides, whose run and subsequent victory brought attention and much-needed food and supplies to his post–World War II homeland.

Also in recognition of the Boston Marathon’s link to the 1896 Olympic Marathon was the Flame of the Marathon Run. In 2008, a specially built cauldron on Hopkinton Town Common was lit with a flame that originated from the warriors’ tomb in Marathon. The Flame of the Marathon Run burned brightly during the 112th Boston Marathon and was later used to light a ceremonious light post outside the Hopkinton Police Department.

In regard to the marathon’s change to 26.2 miles in 1908, the BAA responded sixteen years later for its 1924 edition, stretching out the distance accordingly. Or so it thought. While the Boston Marathon from 1924 to 1926 was understood to be the standard distance, a remeasurement of the course in 1927 revealed that the distance fell short by 197 yards, meaning that the previous three runs were 26.0 miles, 209 yards. All was well—and at 26.2 miles—from 1927 until 1950. Then, due to unmeasured road construction and reconfigurations along the course unrelated to the race, the Boston Marathon from 1951 to 1956 was 25.0 miles, 1,232 yards. Since 1957, the race has been 26.2 miles.

Other than short portions on Chestnut Hill Avenue, Hereford Street, and Boylston Street, the point-to-point course of the Boston Marathon is composed of five routes: Route 135 from the start to Wellesley; Route 16 from Wellesley to Newton; Route 30 from West Newton to Brighton and, later, in Boston and Kenmore Square; Route 9A from Brookline to Boston; and Route 2 in Boston.

Another unique staple of the race is that it is held on the Patriots’ Day holiday, which has simultaneously remained constant while also having often changed. The first race (Monday, April 19, 1897) was held on the four-year-old holiday that commemorated the 1775 battles in the towns of Lexington and Concord that began the Revolutionary War, Paul Revere’s Midnight Ride, and other Massachusetts observances.

For the first seventy-two years, the Boston Marathon was run on April 19 unless that was a Sunday (with two exceptions due to World War II). Since 1969, when Patriots’ Day was designated as the third Monday in April, the Boston Marathon has been held on that fixed day, which is also known colloquially as Marathon Monday.

One other unique mainstay of the Boston Marathon has been its start time, which for over one hundred years was at noon. The first major time change occurred in 2004, when the elite women had their own start at 11:31 a.m., followed by the regular noontime gun for the rest of the field. In 2006, a two-wave start was added as the first ten thousand runners started at noon and the rest at 12:30 p.m. The following year saw an even greater change to the start time when the gun was fired at 10:00 a.m.

The current schedule features multiple starts for the mobility impaired at 9:00 a.m., the push-rim wheelchair division at 9:17 a.m., handcycle athletes at 9:22 a.m., elite women at 9:32 a.m., elite men and the first wave of men and women at 10:00 a.m., a second wave at 10:20 a.m., and a third wave at 10:40 a.m.

Regarding official female entrants, there were none for the first seventy-five years. It wasn’t until the 1972 Boston Marathon, when the governing body Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) included an addendum in its rules handbook, that women could officially run that distance. Nina Kuscsik of New York won in a course-record (CR) time of 3:10:26.

Within the ensuing eleven years, female winners set two world records (WR) at the Boston Marathon—Liane Winter of West Germany in 1975 (2:42:24) and Joan Benoit Samuelson of Maine in 1983 (2:22:43)—doubling the number set by the men’s overall winners, as only Yun Bok Suh of Korea set a WR 2:25:39 in 1947 (John Campbell of New Zealand also set a WR with a 2:11:04 in 1990 in the men’s masters division).

Women also outnumber the men three to one in regard to Olympic Marathon gold medalists who have also won Boston: Benoit Samuelson (1979 and 1983 Bostons; 1984 Olympics), Rosa Mota of Portugal (1987, 1988, 1990 Bostons; 1988 Olympics), and Fatuma Roba of Ethiopia (1997, 1998, 1999 Bostons; 1996 Olympics). To date, Gelindo Bordin of Italy is the only men’s Boston winner (1990) who also won Olympic Marathon gold (1988).

The AAU’s tardiness did not mean women never ran the Boston Marathon prior to 1972, of course. Eight different women (some in multiple years) ran between 1966 and 1971, and the BAA has since recognized Roberta “Bobbi” Gibb of Massachusetts/California (1966, 1967, 1968) and Sara Mae Berman of Massachusetts (1969, 1970, 1971) as champions of those years.

Canadian Jacqueline Gareau won the 1980 Boston Marathon but had to wait a week for her wreath and accolades after an investigation concluded that Rosie Ruiz, the first woman to cross the finish line, had cheated. Photo by Leo Kulinski Jr.

In 1975, the Boston Marathon officially included a wheelchair division when Bob Hall finished in 2:58:00, two minutes under the three-hour limit race director William “Will” Cloney set for Hall to reach in order to receive an official certificate and be officially recognized. This was five years after Eugene Roberts of Maryland had completed the 1970 Boston Marathon in about seven hours sans an official bib number.

The Boston Marathon wheelchair division race in 1977 also doubled as the National Wheelchair Championships, which Hall won. In 1984, the race was officially sanctioned by the BAA, and prize money was added for the first time in 1986. To date, it has recorded fourteen men’s WRs and eleven women’s WRs.

There were also three instances in which the top two women’s finish times were identical (winners Louise Sauvage of Australia in 1998 and 1999 and Christina Ripp of Illinois in 2003) and two one-second victories (winners Masazumi Soejima of Japan in 2011 and Shirley Reilly of Arizona in 2012).

Then there’s the relationship between the Boston Marathon fields and qualifying standards. For the first seventy-three years, men who could run the marathon distance—and, in later years, who could also pass an on-site physical and the muster test administered by race official and staunch gatekeeper John “Jock” Semple—were allowed to compete.

The Boston Marathon is the first major marathon to feature a division for wheelchair athletes. Current fields in the dozens line up in Hopkinton, as shown here in 1998. Courtesy New England Runner.

In 1970, a four-hour qualification certification was required, followed in the ensuing years by several recalculations and stringent age-group standards that were all initially instituted to weed out the unqualified non-athletes and maintain the field. But it all ended up creating an ultimate and exclusive goal that subsequently increased interest and participation. And when field limits capped bib numbers, the Boston Marathon truly became the treasured golden ring.

According to the BBA, including the 2013 race, there have been more than half a million entrants since its inception—550,436, to be precise. From 18 entrants in its first year to a record peak of 38,708 in its 100th in 1996, it took ten years before there were more than 100 entrants for Boston (105 in 1906) and seventy-two years before an entrant field cracked 1,000 (1,014 in 1968).

The running boom of the 1970s provided steady growth in the thousands, with peaks of 9,629 in 1992 and 9,416 in 1995. And after the record centennial field in 1996, and a yearly average of 14,000 from 1997 to 2002, entrant numbers since 2003 have averaged 24,000 a year, with a steady annual range of over 26,000 since 2009.

The Boston Marathon in the early to mid-1980s experienced severe growing pains on its way to an eventual transformation that was imperative for its survival. Decades after the eight-bit entrance fee and the days when a couple people could handle the mailed-in applications and house the dollar bills in a single envelope in a safe, running and marathons were starting to become big business—moneymakers for cities and organizations, as well as top athletes.

When the lock on pure amateurism began to crack, and young and new major-city marathons began to open their financial doors to welcome international elite athletes with appearance fees, transportation, boarding, etc.—among other decision-making foresight—the Boston Marathon’s early response was to maintain its traditions to the point of the exclusion of any growth.

However, a near-fatal attempt to procure answers and sponsors occurred within an unsettling four-year span between 1980 and 1984.

According to public documents found in the Massachusetts Trial Court Law Libraries, late in 1980, Will Cloney, the BAA president and board of governor member, began to meet with Marshall Medoff, a local Boston attorney, with the intention of attracting to the race better promotion and sponsorship to ensure its future. In April 1981, Cloney, by vote of the board, was granted authority to “negotiate” and “execute” in regard to the obtainment of funds all agreed were needed to provide life to the race. Cloney, on his own, again met with Medoff and by September 1981 had signed over rights to Medoff and his newly created sports promotion company, International Marathons Inc. (IMI).

In February 1982, five months after the deal had been made, the BAA learned of the terms, which included the provision that the BAA could not enter into an agreement with a sponsor without first c...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword, by Dave McGillivray

- Foreword, by Roberta “Bobbi” Gibb

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. The Boston Marathon

- 2. Hopkinton: Miles 0.00 to 1.90

- 3. Ashland: Miles 1.90 to 4.95

- 4. Framingham: Miles 4.95 to 7.52

- 5. Natick: Miles 7.52 to 11.72

- 6. Wellesley: Miles 11.72 to 15.93

- 7. Newton: Miles 15.93 to 21.35

- 8. Brighton/Brookline: Miles 21.35 to 24.70

- 9. Boston: Miles 24.70 to 26.20

- 10. Memorial

- Bibliography

- About the Author