![]()

1

WAITING FOR THE END

With German forces reeling back to the Reich in disarray following the hammer blows of the Normandy and Southern France campaigns, the end of the war in Europe seemed tantalizingly near in autumn 1944. Readers of the New York Times thus might be forgiven if, on November 12, they read with skepticism two items that suggested otherwise. In an article entitled “The Nazis Still Hope for a Miracle,” George Axelsson, the paper’s correspondent in Stockholm, noted that the Nazi leadership understood they could no longer win the war. While Axelsson had hinted in an earlier article that the Nazis might conduct a guerrilla war from the Bavarian Alps, he now stressed their determination to prolong the fighting in order to inflict maximum casualties on their enemies, as well as in the hope of splitting the “unnatural” Allied coalition. Despite the looming chaos and massive destruction visited on Germany, it could thus be expected that the Germans would continue to fight doggedly, trusting in yet another of Hitler’s miracles to save them. The other piece, “Hitler’s Hideaway” by London correspondent Harry Vosser, seemed to hint at what that miracle might be. Emphasizing that the Eagle’s Nest, the Führer’s retreat near Berchtesgaden, lay in a virtually impregnable area, Vosser underscored the probability of protracted guerrilla resistance by elite Schutzstaffel (SS) fanatics. Not only had the area been cleared of civilian inhabitants, he claimed, but an elaborate series of tunnels and storage areas for food, water, arms, and ammunition had been carved out within the mountains. With a nicely apocalyptic touch, Vosser also alleged that the Berchtesgaden district, some fifteen miles in depth and twenty-one in length, had been wired in such a way that the push of a single button would suffice to blow up the entire area.1

Fantastic stuff, and likely not taken terribly seriously either by the casual reader or by any American official who happened to read the articles. Not, that is, until after the German counterattack in the Ardennes, the Battle of the Bulge, provided a shocking demonstration of their continued ability to spring nasty surprises. Yet another in a distressingly long line of intelligence oversights—stretching back through the failure to note the defensive potential of the hedgerow country in Normandy to the blunder at Kasserine Pass during the North African campaign—this latest fiasco put the Allied intelligence community on full alert. By its very nature an inexact science, intelligence assessment is a bit like trying to put a jigsaw puzzle together without seeing the original picture. Forced to process a mixture of scattered and imperfect information, some rumor, some planted by the enemy, some accurate, analysts try to take the bits and pieces and create a credible assessment based on an appraisal of enemy intentions and capabilities. Stung by the Ardennes embarrassment and fearful that they had overlooked key evidence, American and British intelligence officials in early 1945 began reexamining information, focusing on three key areas: secret weapons, guerrilla activity, and prolonged resistance in an Alpenfestung (Alpine Fortress, or national redoubt).2

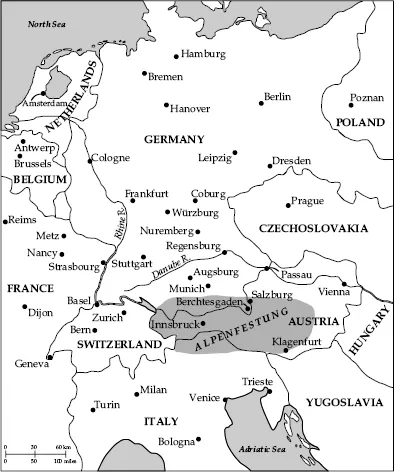

Of the three fears, the latter seemed most likely and threatening. Not only did the Alpine area of southern Germany, western Austria, and northern Italy, with its massive mountain ranges, narrow valleys, and winding roads, offer an ideal defensive terrain, but German forces in Italy had already demonstrated their skill at such fighting. Furthermore, the commander of the German forces in Italy that had so stymied and frustrated the Allies, Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, had just been appointed commander of all German troops in the south. In addition, Allied advantages such as superior air power and ground mobility would to a considerable extent be neutralized by the poor weather and cramped mountainous terrain. Moreover, underground factories in southern Germany were known to be producing the latest miracle weapon, jet airplanes, which might operate from airfields hidden in the mountains. Finally, the human factor could not be ignored, especially since Hitler had already issued any number of “stand and die” orders. Headlines in the Völkischer Beobachter, the Nazi Party newspaper, seemed to confirm such a determination to fight to the last, repeatedly proclaiming, “We will never capitulate,” and “Relentless people’s war against all oppressors.” Indeed, to Churchill and others, the sustained and fanatical German resistance around Budapest and Lake Balaton in Hungary seemed pointless except as a desperate attempt to keep the eastern approaches to an Alpenfestung open for retreating German troops.3 Worried about protracted resistance from a mountain stronghold, aware of the increasing imperatives of the Pacific war, and, not least, determined not to be caught off guard again, Allied intelligence officials set about assembling evidence to confirm their explanation for German actions.

THE ALPENFESTUNG AND REDOUBT HYSTERIA

Once begun, the search resulted in what appeared to be ample substantiation of the reality of an Alpenfestung. Ironically, the notion of a national redoubt, indeed even the name, stemmed from Swiss efforts between 1940 and 1942 to construct a mountain fortress that would serve as a deterrent to any possible German attack. By late 1943, with the tide of war turning against them, the Germans began exploring the possibility of utilizing existing World War I positions in the Dolomite Alps of Northern Italy as the basis for a defensive line running east from Bregenz on Lake Constance to Klagenfurt and then along the Yugoslav border toward Hungary. Since many of these fortifications had remained in relatively good condition, the Germans assumed they could build a strong position rather quickly. Thus, it was not until September of the following year that work began on improving the southern Alpine fortifications. That same September, the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (German Armed Forces High Command, or OKW) ordered a survey of the western and northern Alpine regions with an eye toward linking these with the southern defenses. An engineering staff under Brigadier General August Marcinkiewicz was established at Innsbruck for the purpose of mapping out future defensive positions, although no actual construction began.4

As the Germans began initial preparations for construction of an Alpine fortress, intelligence agents just across the border in Switzerland took note. In late July 1944, Swiss intelligence agent Hans Hausamann sent a report to his government indicating a growing concern that fanatical Nazis would hold out in the Alps until new secret weapons or a split in the Allied coalition produced a decisive turnaround in the war. Swiss intelligence also informed Allen Dulles, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) representative in Bern with whom it maintained regular contact, of the possibility of prolonged German resistance. Although himself somewhat skeptical, Dulles conceded that the Swiss took the possibility of a redoubt seriously, so he dutifully dispatched this information to Washington, where it likely would have been relegated to the wild rumor file except for two coincidental developments in September. First, one of the many American intelligence agents working in Switzerland sent a detailed report to Washington informing of powerful German defenses in the Alps. He spoke of monstrous fortifications with underground factories, of weapons and munitions depots, of secret airfields and stockpiles of supplies. Should the Germans successfully retreat into this fortress, the agent warned, the war could be extended by six to eight months and American forces would suffer more casualties than at Normandy. Of equal concern, he predicted that the Nazis could hold out for two years in the event this last bastion was not assaulted, a situation which might encourage widespread guerrilla activity throughout occupied Germany. Then, on September 22, the Research and Analysis Branch of the OSS issued a scholarly analysis of southern Germany and its potential as a base for continuance of the war. Taken together, these reports nurtured a growing concern in Washington of the possibility of a last-ditch German defense in the south. After all, if the Swiss had created such a stronghold, it seemed only logical that the Germans could and would as well.5

Map 1: Alpenfestung

Once conceived, the fear of an Alpine fortress exercised a strange fascination on American officials determined to avoid any further shocks like the Ardennes offensive. The Germans had certainly undertaken some type of military activity in various areas of the Alps, the idea of a Götterdämmerung struggle in a mountain aerie conformed with Hitler’s personality and previous actions, and there seemed little reason to doubt that the SS would continue to obey orders and fight fanatically. Moreover, Bavaria had been the birthplace of Nazism, and many of its leaders, not least Hitler, displayed an almost mystical attraction to the mountains. Finally, because the redoubt lay in the future American zone of occupation, it would be solely an American problem if allowed to become operational. Unfortunately, despite the undeniable logic of American assumptions, much of the information on which their suppositions were based had been planted by SS-Sturmbannführer Hans Gontard, head of the Sicherheitsdienst (Security Service, or SD) office in the border town of Bregenz. Having intercepted the OSS report to Washington warning of the Alpenfestung, Gontard could only marvel at what seemed to him boundless American gullibility. In late September, in fact, Gontard showed a copy of the report to Franz Hofer, the Gauleiter (party leader) of Tyrol, whom the OSS regarded as a radical Nazi fanatic, in order to demonstrate the ineptitude of the American intelligence service. In a grand irony, Hofer not only perceived how American fears could be exploited by propaganda, but also that the idea of a mountain fortress made sense from a military perspective.6

In early November, therefore, he dispatched a memorandum to Martin Bormann, head of the Nazi Party and secretary to Hitler, that detailed the need for immediate construction of a defense line in the Alps. What had not existed, what the Americans had conceptualized, Hofer now tried to make a reality. In addition to construction of fortifications, he proposed diverting enormous quantities of supplies, munitions, machinery, and military equipment to depots within the proposed fortress area, closing the region to all civilians and refugees, transferring thirty thousand Allied POWs to the Alps for use as hostages, and withdrawing the German army in Italy, still largely intact and undefeated, to the southern defense line. To Hofer’s great distress, however, no one in authority in Berlin showed interest in his suggestions, regarding them as overly pessimistic. Bormann, in fact, refused even to pass Hofer’s memorandum on to Hitler for fear, at a time when great hopes were vested in the Ardennes operation, of being characterized as a defeatist.7

Only Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels recognized the value of an Alpenfestung, and then merely to exploit “redoubt hysteria” among the Americans. Convening a secret meeting of German editors and journalists in early December 1944, Goebbels ensured the dissemination of rumors about a national redoubt by expressly forbidding any mention of such a thing in German newspapers. Then, in January 1945, he organized a special propaganda section to concoct stories about Alpine defensive positions. All the stories were to stress the same themes: impregnable fortifications, vast underground storehouses loaded with supplies, subterranean factories, and elite troops willing to fight fanatically to the last. In addition, Goebbels saw to it that rumors leaked not only to neutral governments but also to German troops. Because Allied intelligence drew on POW interrogations as well as reports from neutral countries, these actions ensured the further dissemination of apparent evidence of the existence of an Alpenfestung. Finally, Goebbels enlisted the aid of the SD to produce fake blueprints, reports on construction timetables, and plans for future transfers of troops and armaments into the redoubt.8

Aided by the efforts of Goebbels’s team, American journalists seized the tantalizing story. In late January, Austrian-born Erwin Lessner reported in a sensational article in Collier’s on an elaborate guerrilla warfare school being run near Berchtesgaden. There, elite SS and Hitler Youth members were allegedly being instructed in partisan warfare, with the goal of harassing the conquerors and terrorizing any Germans cooperating in the occupation. Lessner emphasized that these young guerrillas, given the name Werewolves, would stage lightning raids out of an Alpine fortress, trying to inflict as much damage and as many casualties as possible before retiring back to their mountain citadel. Although confident that this guerrilla war would ultimately fail, Lessner warned that it could nonetheless cause grave difficulties if not taken seriously by the Allies. After all, he pointed out, the Nazis had the advantage of having studied all of the resistance movements that had opposed their rule, and so had a clear understanding of how to conduct an effective underground war. In Lessner’s assessment, the Nazis meant guerrilla war to be another Vweapon, which, after all, in German stood for Vergeltung (revenge, retaliation). The goal, then, was not victory as much as it was vengeance.9

A few days later the Swiss added fuel to the smoldering fire. The Zurich newspaper Weltwoche, under the headline “Festung Berchtesgaden,” reported on February 2 that “reliable reports out of Germany contained technical details of the construction of a Berchtesgaden redoubt position with the Obersalzburg as the nerve center.” As the nearest neighbors to Germany, the Swiss had instant credibility, which was reinforced in the article by the accumulation of detail about the alleged mountain fortress. Running along the rugged crest of the mountains, the defensive system,

with its installations of machine gun nests, anti-aircraft positions, radio transmitters, and secure bunkers at the passes provide evidence that the romantic dream [of sustained resistance] is taken seriously and that good German thoroughness is once again being directed at a fantastic goal…. In the heights around the Königssee, in the old salt mines in the area, in hollowed out mountains and along valley roads, little by little massive depots of war material, munitions, repair and maintenance shops are being established. Industrial facilities to produce war material are being built there. Airplane factories for jet fighters are being erected, huge fuel depots put in place…. Underground airfields and hangers stand ready…. Grain and potato supplies have been gathered.

“The fortress Berchtesgaden,” the article emphasized, “is no legend,” with its political purpose more important than its military significance. It was, the author declared, intended to keep alive “a bacterial culture of National Socialist ideology and strength” until the day when a renewed Nazism would again seize power.10

Little over a week after the Weltwoche article, a long piece in the New York Times Magazine, “Last Fortress of the Nazis,” seemingly confirmed the Swiss assertion. The author, Victor Schiff, almost certainly had read the Swiss article, for much of his detail mirrored the information contained in the Zurich newspaper. Schiff asserted that the Nazis, having nothing to lose, would fight bitterly to the last in the hope of a reversal of fortune, and that the fight would be carried on by Hitler’s fanatical elite, the SS. He went on alarmingly:

It is noteworthy that since the beginning of the Russian offensive very little has been heard of the SS troops on the Eastern Front…. It looks as if the Wehrmacht and Volkssturm are being deliberately sacrificed in rear-guard actions…. SS formations are likely to retreat swiftly southward to a region already selected as the last theater of operations in Europe…. It will stretch from the eastern tip of Lake Constance to the approaches of Graz in Styria …, [with] an approximate length of 280 miles and an average width of 100 miles, and a total area slightly larger than Switzerland…. It would be comparatively easy to defend this “fortress” for a very long time with some twenty divisions … behind the formidable barrier of the gigantic chain of central and eastern Alps…. The few gaps in the valleys … can be sealed with more fortifications and pill-boxes dug in the rocks, and [there is] little doubt that the Todt Organization is already being used to the limit for that purpose…. We can assume that the Nazi High Command has started hoarding reserves of arms, munitions, oil, food, and textiles in a series of underground depots within the Alpine quadrangle.

Pointing to the difficulty posed by such an Alpine fortress, Schiff observed, “If they succeeded in holding out till the autumn of 1945, operations would have to come to a standstill till the spring of 1946 … [because of] the impossibility of any real warfare in such regions during the winter.” Ending his gloomy assessment, Schiff raised the specter of “a monstrous blackmail,” noting, “Since D-Day all the main political hostages from Allied countries have been moved by the Gestapo [German secret police] from various parts of the Reich into this Alps quadrangle.”11

Nor could this article be dismissed as wild speculation, for Dr. Paul Schmidt, spokesman of the German Foreign Office, gave a speech on February 13 to foreign correspondents in which he boasted, “Millions of us will wage guerrilla warfare; every German before he dies will try to take five or ten enemies with him to the grave.” As another journalist, Curt Riess, argued, such talk played to the element of Todesverlangen (longing for death) allegedly rampant in German culture. Just as Wagner portrayed the world’s end as a “Twilight of the Gods,” so Hitler and Goebbels wanted their own Götterdämmerung and hoped to convince average Germans that their death was a “fate full of meaning.” By the end of the month, even the Soviets had gotten in on the action, warning in Pravda that the Nazis had made complete preparations for setting up “underground terrorist organizations” for the purpose of sabotage and revenge.12

Adding weight to these assertions, Dulles communicated his growing concern to Washington, stressing on January 22 that “The information we get here locally seems to tend more and more to the theory of a Nazi withdrawal into the Austrian and Bavarian Alps, with the idea of making...