![]()

1 / How Real Are the Elementary Particles?

AS OUTLINED IN ARTHUR Zajonc’s introduction, the tenth Mind and Life meeting took us on a long journey, from the simplest constituents of matter far into the complexity of human consciousness. This book tracks that journey as it played out over the course of a week in a packed room at the Dalai Lama’s home on the threshold of the Himalayas. How to begin tracing this ambitious, seemingly immense arc?1 We will start with the statement that launched a presentation by Steven Chu, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist: “The single most important thing we know is that the world is made of atoms. This is the view that most physicists today, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, would agree with.”

Steven Chu (left) in the hot seat.

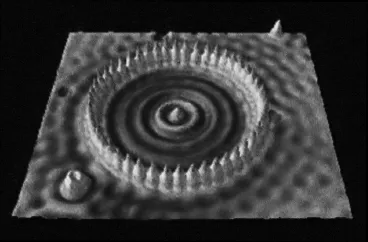

A graphical rendering of iron atoms on a copper surface, as seen throughout a scanning tunneling microscope.

What? some of the monks in the room might have thought. Are the mountains, the rivers, the trees, animals and human beings, all made of atoms? And what about consciousness? Is that too made of atoms?

The room was filled to capacity, charged with energy, and alight with the rainbow colors of Tibetan paintings and flowers cut from the Dalai Lama’s garden outside. Steven Chu was looking very relaxed in the presenter’s hot seat, and his boyish ear-to-ear grin signaled eager anticipation as much as any nervousness about being in the spotlight.

But there was no laughter when Steven Chu showed his slide—a photograph of atoms! At the sight, a murmur passed through the room, and a small quake rippled through the rows of bald heads. The Dalai Lama’s face lit up and his mouth opened in astonished delight.

“Is this the picture of an atom?” he asked.

“Not a drawn picture,” answered Steven, “a real picture! This is a picture of iron atoms placed on the surface of a piece of metal.”

“But those are individual atoms?” the Dalai Lama persisted, as if not quite believing.

“Yes,” said Steven. “Individual atoms. Single atoms. Each of these little bumps is one atom.”

“And the wiggles?”

“These wiggles are the electron waves in the metal that are scattering off of these iron atoms. We don’t know for sure all the parts of these atoms. But in a certain sense, we can now see them.”

“So this is a cluster of atoms?”

“Correct. One, two, three, four, five,” answered Steven.

“Do the atoms stay right where they are? Or do they start to stray?” asked the Dalai Lama.

“They would stray if they were at room temperature, because of thermal motions,” Steven responded. “You have to get it very, very cold for them to stay still, as in this experiment. However, everything inside the atom is still moving. Within the atom there is a nucleus—the core—and the electrons. The electrons are moving. Within the nucleus there are quarks, and they are moving. The whole frozen atom is just …” Steven thought hard and then offered, “It’s like a bus that’s stopped in traffic. The people inside are still moving, they’re hot.” He fanned himself for a moment in empathy with these particle passengers,2 then continued. “So atoms are made of other particles: electrons in the periphery, and protons and neutrons in the core. And even the protons and neutrons are made up of still more simple fundamental particles called quarks. And we know not only that there are six quarks, but each of the six comes in three different colors, as we say. Beyond that, we know of no other particles.”

“Wonderful, wonderful!” the Dalai Lama said, smiling with a look of happy complicity. His fascination with atomic particles is notorious, though perhaps a mystery to the monks.

* * *

THE ATOM: A LITTLE HISTORY OF A BIG IDEA

To find the origin of the concept of the atom, we must go back more than two millennia to the town of Abdera in Asia Minor, to the Greek philosopher Democritus (c. 460–370 B.C.). History credits Democritus’s teacher, Leucippus of Miletus, with the earliest expression of the idea, but little is known about him other than that he planted a seed that inspired his brilliant student. Democritus started with the assumption of the impossibility of dividing things ad infinitum. Thus the essential components of reality must be particles that cannot be divided further, and those particles were called atoms, which literally means “without division.” They cannot be divided further because they do not contain empty space, or “void.” In fact, the shape and existence of all things are determined by differences in the shape, position, and arrangement of the atoms and the proportion of void in the substance. It was also believed that the human soul consists of atoms and void.

The philosophy of Democritus was taken up and expanded by Epicurus of Samos (341–271 B.C.) in Greece. Whereas Democritus was highly respected in Abdera, Epicurus was not in the more rigid Greek heartland, and even less was Lucretius (c. 99–55 B.C.), who imported the atomistic theories into Rome a couple of centuries later with his great didactic poem De Rerum Natura (The Nature of Things). Most of the voluminous work of both Epicurus and Lucretius is lost, apparently for the same reason: having been destroyed by their contemporaries and later philosophers and by the government and religious authorities of the time.

What was the reason for this acrimony against them? Interestingly, and as is all too familiar in modern times, it was mostly that their atomistic philosophy did not leave Epicurus and Lucretius with much respect for the gods. Epicureanism was often charged in antiquity with being a godless philosophy because its mechanistic explanations of natural phenomena such as earthquakes and lightning, all based on atoms and their movements, were seen as displacing the will of the gods. Epicurus pointed to the many evils and calamities surrounding us as evidence that the world cannot be under the providence of a loving deity. Even if the gods exist, they have no concern for us, and therefore we should live without regard for them, cultivating tranquility of mind as the supreme achievement of man. While Epicurus was teaching tranquility of mind in ancient Greece, in a very distant part of the world a certain Gautama Buddha was striking a similar chord with an essential point of Buddhism. Chance, synchronicity, convergent mental evolution—take your pick.

For Epicurus, the human mind was also something physical, and he identified mental processes with atomic processes. Whereas atoms are eternals, he reasoned, the mind is not. Just like other compound bodies, the mind ceases to exist when the atoms disperse. This would be so even for the minds of the gods, assuming that they exist.

The Roman Lucretius, who was a great poet, added the dimension of love of nature to the dry philosophy of Epicurus. Particularly in the sixth chapter of De Rerum Natura, he articulates the basic atomistic teachings, but also describes some of the controversies between Democritus and Epicurus. Lucretius held that atoms do not move, as Democritus had claimed, in straight lines in all directions and in accordance with the laws of “necessity” (anangke). Instead, they move at random and unpredictable moments, and they deviate ever so slightly from a regular course, taking paths and colliding in ways that are not completely determined by necessity but contain some element of chance. This theory of atomic “swerve,” or clinamen, is a crucial feature of the Epicurean–Lucretian worldview because it provides a physical foundation for the existence of free will. On this basis, Epicurus, Lucretius, and their adherents are remembered as being “able to explain the universe as an ongoing cosmic event—a never-ending binding and unbinding of atoms resulting in the gradual emergence of entire new worlds and the gradual disintegration of old ones. Our world, our bodies, our minds are but atoms in motion. They did not occur because of some purpose or final cause. Nor were they created by some god for our special use and benefit. They simply happened, more or less randomly and entirely naturally, through the effective operation of immutable and eternal physical laws.”3

This view sounds as if it might have been inspired by Jacques Monod or Stephen Jay Gould speaking from the chair of contingency. And the notion that all is made of atoms appears to be in harmony with Steven Chu’s pronouncement that the world is made of atoms. What is new? One difference is that the ancient atomists were philosophers for whom atoms were conceptual entities, the product of logic. Our modern physicists claim to have demonstrated the existence of atoms empirically, through physical experiments. In fact, Steven Chu points proudly at his picture of atoms. We have seen them!

Another advance was the discovery, which Rutherford had made by 1910, that the nucleus accounts for 99.9 percent of the mass of the atom but takes up only a tiny part of its volume. An atom’s nucleus occupies the same space as a grain of rice in a football stadium. Void is thus the main reality of an atom. By setting the void inside the atoms, Rutherford parted ways with the Greek atomists, who believed that atoms were small particles of condensed mass with the void outside them.

But this not the end of the story. After Rutherford came Bohr, Heisenberg, and Schrödinger with their quantum mechanics. Their discovery was stunning, and challenged many crucial elements of the age-old picture of atoms and particles. To start with, they realized that atoms and subatomic particles cannot be ascribed any well-defined trajectory. According to Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, if you know the position of a particle with accuracy, you lose any accuracy in the knowledge of the velocity of that particle, and vice versa. But if two or more particles of the same kind (for instance, two electrons) have no well-defined trajectory, we cannot follow their track, and we can easily mistake one of them for another. As a consequence, particles have lost their identity and individuality! Schrödinger was so puzzled by this new truth that he seriously wondered what was left of the concept of an atom or a particle in quantum physics. “What is a particle which has no trajectory or no path?”4 he asked in dismay.

* * *

“Electrons and quarks are considered our most elementary particles,” Steven continued. “We can think of an electron or quark as a tiny little particle that creates a force field. Now this is very strange: our current understanding of these particles is that they have no size. They are infinitely small. The particles are points, and we describe them in terms of their field lines”—in other words, the forces they can exert on other particles in the universe.

The Dalai Lama asked for clarification: “Are you referring to protons, neutrons, and electrons, or to quarks?”

“Protons are not elementary because they are made up of quarks,” Steven answered. “Just like the atom is no longer elementary, as it is made up of other pieces.”

“And the electron?”

“The electron is elementary, as far as we know. And it is very small. How small is it? If the atom were the size of the Earth, the electron would be smaller than one millimeter. How do we know that electrons are so small? We actually take electrons and throw them at each other. Electrons that have a size would bounce differently from electrons that do not have a size. We can mathematically predict the conclusion that they have no size. They are just points. The particle becomes just the field.”

The Dalai Lama was intrigued, but skeptical. “Do they really bounce off of each other? Do they provide an obstruction to an incoming entity?”

“Yes!” Steven said, grinning.

Matthieu Ricard jumped in, unconvinced: “That means they have size!”

“Yes!” Steven repeated, enjoying the paradox.

“This is interesting,” the Dalai Lama said. “You speak of something that is only one point, and has no spatial dimension. However, if you hit it from the east side, then it must have a west side. This would imply some type of spatiality.”

Steven agreed. “You have to imagine that there’s an east side and a west side, a front and a back.”

The Dalai Lama pushed this logically: “If it really is dimensionless, then if you hit it from one side, you must simultaneously be hitting it from the other side.”

“That’s correct,” said Steven.

“That’s very weird,” the Dalai Lama frowned. “There was a fourth-century Buddhist philosopher who refuted the notion of indivisible elementary particles as the simplest building blocks of the physical universe. His argument was that so long as a particle retains a material nature, it will have spatial dimensions and different sides, which are not indivisible. You will probably have to invite this fourth-century Buddhist philosopher to respond to you.”

Steven’s answer was spontaneous: “Can you be my graduate student?” It was not the first time that an eminent scientist had expressed such wishful appreciation, and the Dalai Lama laughed.

“If I were a bit younger, yes!”

In spite of the humor that graced the discussion, not one of the Tibetan monks seemed comfortable with these strange electrons. Heads shook incredulously, and dismayed faces turned toward the Dalai Lama as if looking to him for some solution to the conundrum. The monks whispered among themselves, and rustlings of consternation passed also through the wider circle of observers. Arthur made an effort to restore silence and attention and Steven tried to move on to the next topic, but the Dalai Lama insisted on pursuing this mystery of the dimensionless particles. He slapped his hand on his fist in a gesture of debate.

“You say that it has not been ascertained that electrons have no spatial dimension. It has simply been ascertained that spatial dimensions have not been possible to detect. The controversy would dissolve if you say that maybe it has a spatial dimension, but too small for us to detect. Is there any reason that this is not an open possibility?”

“That is definitely a possibility,” Steven conceded. “This description indeed has fundamental problems. In particular, it leads to a contradiction between our two most cherished theories, quantum mechanics and the theory of gravity.”

Particles and the Nature of Reality

Later we returned to this theme. Steven had enjoyed the astonishment that his description of the dimensionless electron caused and was eager to turn the screw further. “We know of three different types of electrons,” he said. “One is the normal electron. If you spend a lot of money, you can make the other two types of electrons by smashing particles together. These other types of electrons are still pointlike, although they have more energy and mass. They can also have either positive or negative charge, particles or antiparticles.

“And now you have a very strange situation: a negative point particle and a positive point particle are attracted to each other. If you bring the particles together on top of each other, they actually collapse and annihilate each other. This is all self-consistent.” Steven fell silent. His statement seemed to hang in the air as his audience pondered. Arthur asked if anyone had a question, but no one spoke. Finally, Steven broke the spell with a comment that brought an appreciative laugh from the Dalai Lama: “The fact that we’re self-consistent does not mean we’re right.”

Steven’s description of positively and negatively charged particles started us off on a path that would lead eventually to a very deep discussion on the nature of physical properties. But first he explained how the property of an atom’s size is related to the charge of its particles. “In an atom, the electron is attracted to the nucleus, which is positive.” We were dealing here with normal negative electrons, of course, not the weird and expensive ones that Nobel Prize-winning physicists produce in the laboratory. “The electron wants to get closer and closer to the nucleus as they attract each other. What stops it?” He paused to gauge the effect of his question, but nobody offered a guess.

“Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle tells us that, as the electron gets closer and closer to the nucleus, its momentum gets bigger and bigger.” To be more precise, it is not the specific value of the momentum that gets bigger, but rather, as you confine an electron to a smaller region, with a small uncertainty in the position, then the uncertainty in its momentum increases. “But that momentum requires energy. The nucleus and the electron cannot be packed too close to each other because there is not enough energy.”

Steven grinned like the Cheshire cat, and continued, “The energy gain of this momentum has nothing to do with the intrinsic forces of attraction. What’s amazing is that the energy gained by the particles getting closer cancels the energy lost in bringing them closer. You lose energy in the process of getting these particles closer, but you gain the energy of the uncertainty principle. The balance of those energies defines the statistical size of the atom, the place where it’s mostly stable and the electrons can hardly get any closer.” Here Steven added his personal witness to the abstra...