eBook - ePub

The Atlanta Ripper

The Unsolved Case of the Gate City's Most Infamous Murders

- 147 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

An examination of the unsolved mystery of the Jack the Ripper-style serial killer who terrified early 20th century Atlanta, Georgia.

As Atlanta finished rebuilding after the Civil War, a new horror arose from the ashes to roam the night streets. Beginning in 1911, a killer whose methods mimicked the famed Jack the Ripper murdered at least twenty black women, from prostitutes to working-class women and mothers. Each murder attributed to the killer occurred on a Saturday night, and for one terrifying spring in 1911, a fresh body turned up every Sunday morning. Amid a stifling investigation, slayings continued until 1915. As many as six men were arrested for the crimes, but investigators never discovered the identity of the killer, or killers, despite having several suspects in custody. Join local historian Jeffery Wells as he reveals the case of the Atlanta Ripper, unsolved to this day.

As Atlanta finished rebuilding after the Civil War, a new horror arose from the ashes to roam the night streets. Beginning in 1911, a killer whose methods mimicked the famed Jack the Ripper murdered at least twenty black women, from prostitutes to working-class women and mothers. Each murder attributed to the killer occurred on a Saturday night, and for one terrifying spring in 1911, a fresh body turned up every Sunday morning. Amid a stifling investigation, slayings continued until 1915. As many as six men were arrested for the crimes, but investigators never discovered the identity of the killer, or killers, despite having several suspects in custody. Join local historian Jeffery Wells as he reveals the case of the Atlanta Ripper, unsolved to this day.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Atlanta Ripper by Jeffery Wells in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781614231820Subtopic

African American History1

TIME AND PLACE

Atlanta in the Early 1900s

Before diving into the actual murders themselves, it is important to understand the time and place in which these events occurred. While it may be easy to associate Atlanta today with skyscrapers, amusement parks, professional athletic teams and, unfortunately, long commutes and jammed interstates, the Atlanta of the Ripper murders was much different. The massive urban sprawl that is evident in the city today was not always the case. As a matter of fact, Atlanta in the early 1900s was a tighter-knit community than one might think.

ATLANTA IS BORN

Atlanta actually owes its existence to railroads—ironically, the place near where more than a few of the Ripper's victims were found. At that time, the State of Georgia owned the Western and Atlantic Railroad. By 1837, a few engineers from the Western and Atlantic staked out a place a few miles from the banks of the Chattahoochee River to locate the southern end of a rail line they hoped to build that would connect to Chattanooga, Tennessee. The location of this “end of the line” was billed as Terminus, although the city was not incorporated at this time. In 1843, the name of the community was officially changed to Marthasville in honor of Governor Wilson Lumpkin's daughter, Martha Lumpkin Compton. She is interred at Atlanta's historic Oakland Cemetery. In 1845, the city was officially renamed Atlanta, the feminine version of Atlantic, a name that reflected the hamlet's destination as the end of the Western and Atlantic Railroad.

Immediately upon its founding, Atlanta charted a different course from the rest of the larger cities in Georgia. While the slave population in many of those cities, like Savannah and Macon, was significant, Atlanta's slave population was much smaller. The economy of the city was also controlled by merchants and those associated with the railroad industry, unlike the older cities of Georgia, whose economies were fueled by plantations and smaller farms. This type of economy would serve Atlanta well in the future, but it did make the city a target during the Civil War. In that epic conflict, Atlanta not only served as a transportation center but also provided a base of manufacturing. Located in the city were the Atlanta Arsenal and the Gate City Rolling Mills. The Atlanta Arsenal provided ordnance and other supplies for the Confederate armies that were fighting in Georgia, Tennessee and Alabama, while the Gate City Rolling Mills produced iron that could be turned into rails. In addition to these resources, Atlanta also had a Confederate hospital and military quartermaster depot. Other industries located in the city were the Atlanta Sword Manufactory and Spiller and Burr, a pistol factory.

As with any city that offered job opportunities in the manufacturing sector, the population of Atlanta swelled. In 1860, there were nine thousand people living in Atlanta, but by 1865, that number had swollen to over twenty-two thousand—a testament to the pull of the industrial base that was starting to form there.

THE CIVIL WAR COMES TO ATLANTA

Although it had been of strategic importance to the Confederacy throughout the war years, Atlanta really did not see much of the action of the war until the arrival of one of the most famous figures that came out of the conflict—General William Tecumseh Sherman. In early 1864, Sherman received orders from General Ulysses S. Grant to push as far into the interior of Georgia as he could and inflict as much damage as possible on the Confederacy's war resources there. Leaving Chattanooga shortly thereafter, he began his march toward Atlanta—a city he claimed did more to damage the Union cause than any other city except Richmond, Virginia. Engaging Confederate troops in General Joseph E. Johnston's Army of Tennessee, he pushed onward, winning battle after battle, including those at Dalton, Resaca, New Hope Church, Atlanta and Jonesboro. The only Confederate victory came at Kennesaw Mountain, but it proved to be hollow, as Sherman was still able to regroup and push forward.

The Union general entered Atlanta on September 2, 1864. The city had been pounded by Union artillery for forty days, resulting in much destruction to the city's businesses, infrastructure and residential sections. Sherman and his army remained in Atlanta until they began their infamous March to the Sea on November 15, 1864. Before leaving, however, Sherman ordered that public buildings, blacksmith shops, factories, railroad facilities and any other places that might aid the Confederate war effort be leveled and set afire. Union troops, eager to destroy the “workshop of the Confederacy,” began to set buildings ablaze before they could be leveled, a decision that caused fire to spread and destroy many private homes and buildings not targeted for destruction.

THE PHOENIX RISES FROM THE ASHES

With only $1.64 of useless Confederate money in the city's treasury after the occupation of Federal troops, the citizens of Atlanta started the long process of rebuilding. As they had done prior to the Civil War, railroads once again provided the economic impetus to make Atlanta a thriving city of commerce, but this time, the growth would be much more painful. Over the next few months, the city's rail lines were running again. Soon, there were no fewer than 150 trains arriving in the city daily. Not long afterward, the city would boast that it was the “Gate City” and the “Chicago of the South.”

The thriving railroad industry also led to the redevelopment of commerce and manufacturing in Atlanta. As Georgia had been a productive cotton state before the war, the crop was destined to make a comeback, which it did during the late 1800s. With cotton so readily available, and the sharecropping system providing labor at a reasonable price, it was inevitable that a factory industry would crop up that made use of the South's most precious crop. Indeed, this came in the form of textile mills. Once again, cotton was helping to drive the economic engine in the state, and Atlanta was poised to take the lead in textile manufacturing.

With all these opportunities for work in Atlanta, it was no wonder that the population jumped by over twenty thousand people. In 1900, the population stood at ninety thousand. To top off this successful run, the state capital was moved from Milledgeville to Atlanta in 1868. It appeared that the phoenix was rising from the ashes Sherman left behind.

AFRICAN AMERICAN MIGRATION

The growth of Atlanta led to the migration of many people to the area as they sought jobs and better lives. African Americans were no exception. The development and growth of centers of higher learning for African Americans—like Spelman College, Clark College, Atlanta University, Morehouse College and Morris Brown College—drew many young African Americans to the area, many of whom stayed after they finished their matriculation. Like the overall population of Atlanta, the number of black Atlantans grew tremendously. In 1860, there were fewer than two thousand African Americans in Atlanta; however, by the end of the century, that number had swelled to over thirty-five thousand.

Contributing to this growth, along with the venues of higher education mentioned already, were the lucrative business and social climates that existed in the city for black residents. Key among those were Sweet Auburn and the West End, both of which were thriving black neighborhoods and business districts. This climate produced such notable black entrepreneurs as Alonzo Herndon, who in 1905 established the Atlanta Life Insurance Company. By 1910, the company had over twenty-five thousand policyholders, no small accomplishment for an African American–held company considering the many obstacles that stood in its way just forty years after the close of the Civil War and the end to slavery in the South.

Atlanta was also fortunate to be the home of the early civil rights movement. As home to such notable institutions of higher learning as Atlanta University and Spelman College, it was inevitable that the Gate City would attract well-known African American academics. Notable among those was Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois, a professor of sociology at Atlanta University. The first black man to receive a PhD from Harvard University, Du Bois climbed the ladder of academic success and arrived in Atlanta in 1897. There, he taught alongside such people as Adrienne Herndon, the wife of Alonzo Herndon. Du Bois, who would go on to help found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and author the groundbreaking The Souls of Black Folk, was a moving force behind the Niagara Movement; edited the NAACP's magazine, The Crises; and became one of the leading voices in black America of the day. His counterpart—and in many instances, his opposite—Booker T. Washington, while not a resident of Atlanta, did give his famous “Atlanta Compromise” speech at the 1895 International Cotton Exhibition held in the city. The two towering figures would be integral to the debate over civil rights in the early 1900s and would become the most well-known African American figures in the nation in many respects.

THE 1906 ATLANTA RACE RIOT

As much as Atlanta had progressed in the years after the Civil War, and as much as it had become what many considered a haven for African Americans on the rise, it must be remembered that not everything had advanced. There were many people in Atlanta who held very backward views about race, and as some historians have noted, there were most definitely two Atlantas. That would be painfully obvious in 1906.

As the population of Atlanta began to grow, the municipal services offered by the city were stretched thin, and competition for jobs between black and white laborers was intense—a situation that made some whites in the city resent the growing number of African Americans who had come to live there. In addition, the emergence of a black upper class made many whites in the city uncomfortable. This came to a head during the 1906 gubernatorial election in Georgia. The candidates were Hoke Smith, who had at one time been the publisher of the Atlanta Journal, and Clark Howell, an editor with the Atlanta Constitution. The papers have since been merged, but in the early twentieth century, they were separate entities vying for readership in Atlanta and beyond.

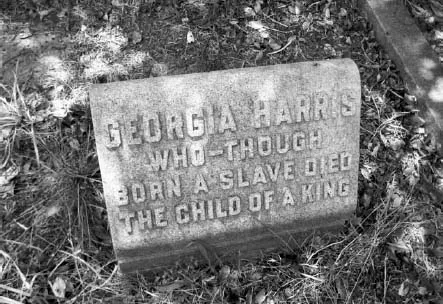

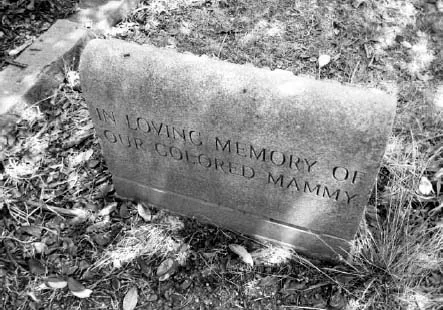

In Oakland Cemetery, even the graves were segregated, but a few African Americans, like Georgia Harris, were buried in the white section near their employers.

The inscription on the back of Georgia Harris's marker reflects the ideas of an era many would like to forget.

At that time in Georgia history, candidates for office often tried to “outdo” each other on issues such as white supremacy and keeping black Georgians from advancing politically and economically. This particular election was no exception. Both Smith and Howell debated back and forth, mainly through their respective news organizations, about how the other was not the right candidate for the job because he could not be trusted to help keep “blacks in their place.” Smith argued that the only way to accomplish such a goal was to disenfranchise black voters. Howell, on the other hand, argued that the white Democratic primary and poll tax were sufficient methods to accomplish such ends. Howell further blasted Smith for being a bit of a lightweight when it came to advancing the idea of white supremacy in the state.

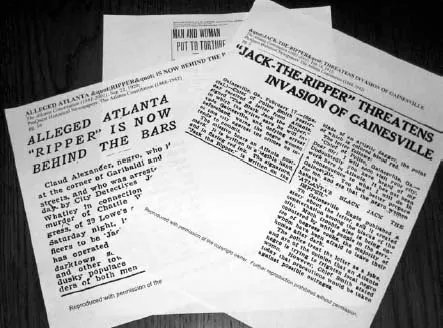

Articles from the Atlanta Constitution after 1911. This is evidence that many felt the Ripper was still at work, even years later.

To make matters worse, both newspapers were currently running articles about a series of alleged assaults on white women by black men in Atlanta. In addition to the Journal and Constitution, other papers, such as the Atlanta Georgian and Atlanta News, were filled with stories about black-on-white crime. These papers argued that the city was in danger if the blacks were not kept in their place and the saloons that black men frequented were not shut down. The papers added to the already growing racial tension in the city, a tension that no doubt had a lot to do with the advancements blacks had made socially, politically, educationally and economically since the close of the war. In September 1906, papers in Atlanta were carrying the news of four alleged attacks on white women that were supposedly perpetrated by black men in the city. It was the proverbial straw that broke the camel's back.

On Saturday, September 22, a mob of white men descended on downtown Atlanta. Enraged by the incendiary language and coverage in the press of alleged crimes, these men were bent on revenge, and violence was not too great a price to pay to exact it. City leaders, including Mayor James G. Woodward, tried to calm the mob, but to no avail. The men soon turned their anger on the central business district, attacking blacks on the streets and pulling them out of streetcars. Black-owned businesses were targeted, including the barbershop of Alonzo Herndon. Leaders in the black community called a meeting at Brownsville, an African American community near downtown Atlanta. Fearing that the meeting might be for the purposes of organizing an attack on the white community, the local police and state militia moved in and adjourned the meeting, making at least 250 arrests of black men. For the next few days, fighting continued, although somewhat diminished due to the fact that the state militia had already moved in to town and was patrolling the streets of the city. By Tuesday, September 25, the riots were over.

Although there is debate over the number of blacks kil...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Dedication1

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Time and Place: Atlanta in the Early 1900s

- 2. The Ripper Phenomenon

- 3. 1911: The Year of the Atlanta Ripper

- 4. Beyond 1911

- 5. Theories Abound

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Further Reading

- About the Author