![]()

Part One

History and Culture

![]()

Memphis in the Twentieth Century

In 1905, a correspondent for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported that “the only difference between Memphis and Hell is that Memphis has a river running along one side of it.” As this comment suggests, rhetorically flogging Memphis was something of a cottage industry during the twentieth century as journalists, filmmakers and novelists highlighted the city’s penchant for violence and provincialism while often overlooking the Bluff City’s significant contributions to American culture.

Perhaps the greatest writer to explore Memphis was William Faulkner. A native of north Mississippi, Faulkner was recognized as one of the century’s most important writers and was awarded the Pulitzer and Nobel Prizes for his body of work. The city looms large in his novels Sanctuary and The Reivers. In Sanctuary, Faulkner describes Memphis as a den of iniquity. The novel centers on the kidnapping of an Ole Miss coed who is hidden in Miss Reba’s brothel in downtown Memphis. The kidnapper is a Memphis bootlegger named Popeye and was based on a real-life Memphis gangster named Neill “Popeye” Pumphrey. In Faulkner’s Memphis, prostitution is so commonplace that a visiting Mississippi family moves into Miss Reba’s, which they mistakenly believe is a boardinghouse. Two weeks pass before they discover that more than boarding is going on. Faulkner revisited the “Memphis as a lawless city” theme with his last novel, The Reivers. Set in 1905, it is the story of an eleven-year-old boy who travels from north Mississippi to Memphis in a stolen automobile with two of his father’s employees. While there, he stays in Miss Reba’s brothel, where he is “knife-cut in a…whorehouse brawl” and becomes entangled in an illegal horse race and the theft of a gold tooth.

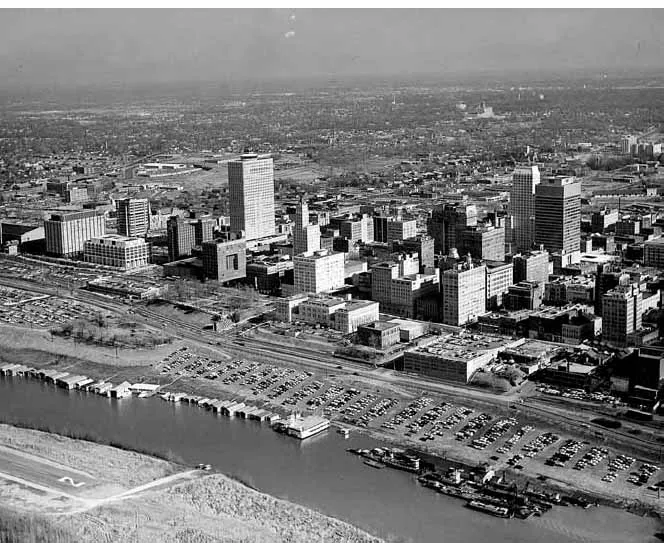

Memphis about the time it was depicted by Time magazine as a “decaying Mississippi River town.”

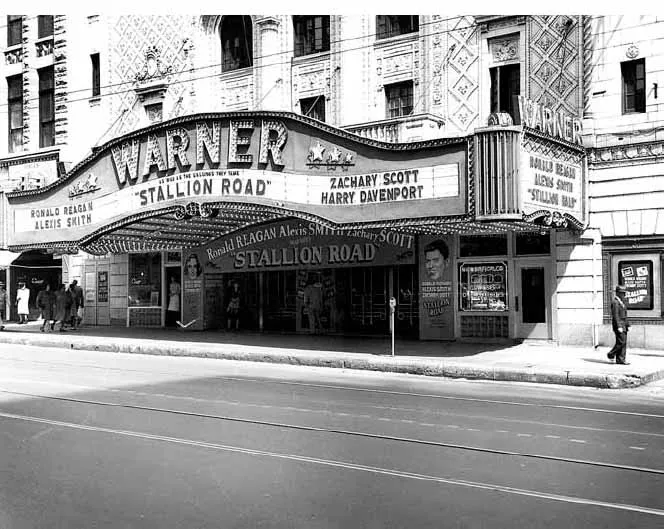

Hollywood also reflected the view that Memphis was a sinful place with the release of several films. The first of these was Hallelujah!, a musical with an all-black cast directed by King Vidor. Filmed in Memphis and Arkansas in 1928 and released the following year, the story revolves around an African American sharecropper who travels to Memphis to sell his cotton crop. While there, he visits a saloon, where he is seduced by a female dancer and robbed. Like in Faulkner’s work, an innocent person from the country travels to the big city of Memphis and is corrupted. This theme is again explored in United Artists’ Thunder Road, starring Robert Mitchum. The main character in the film is Luke Doolin, a west Tennessee moonshiner who sells his homemade corn liquor in Memphis. Mitchum’s character is a lonely rebel who refuses to cooperate with a gangster attempting to control the Memphis liquor trade while also being pursued by federal agents. Doolin is not really corrupted by the city, but he does lose his life when he defies the criminal culture of Memphis.

King Vidor’s Hallelujah! was one of several twentieth-century Hollywood films that depicted Memphis as a raucous, sinful place.

Another movie set in Memphis was the Republic Pictures release Lady for a Night, starring John Wayne and Joan Blondell. Set during Reconstruction, Wayne portrays, in the words of one of the cast members, the “political king of Memphis,” and Blondell plays the owner of a floating casino who desperately wants to be accepted by Memphis society. In the movie, African Americans are portrayed more sympathetically than in other movies of the time. For example, in the street scenes that open the film, African American men are wearing suits, ties and bowler hats, and black women are dressed in expensive gowns. Also, John Wayne’s character’s most trusted advisor is an African American.

In contrast to the raucous image we’ve been discussing, Memphians were also portrayed as being provincial and very conservative. The Baltimore journalist H.L. Mencken described the Bluff City as “the most rural-minded city in the South,” and historian Charles Crawford noted that Memphis was “a small town with a lot of people in it.” This prudish reputation was in part due to the notorious chairman of the Memphis Board of Censors, Lloyd T. Binford, who banned hundreds of films during his twenty-five-year tenure. Binford reasoned that movie censorship was necessary because “there’s a certain amount of the devil in all of us.” For example, the film The Moon Is Blue was not shown in Memphis because the script included the word “virgin.” Other films banned for being “lewd or indecent” included Forever Amber, Rebel Without a Cause and The Wild One. As one might expect, Memphis’s support of Binford was widely condemned in the national press. “Censorship, Memphis-Binford style, concededly provides an extreme case of capricious and mischievous interference with the freedom of adults,” wrote a correspondent for Collier’s magazine.

Memphians flocked to the movies to see their hometown depicted in such films as Thunder Road and Lady for a Night.

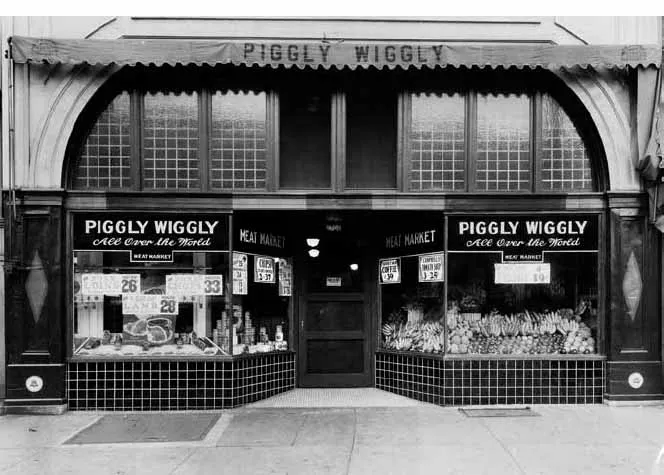

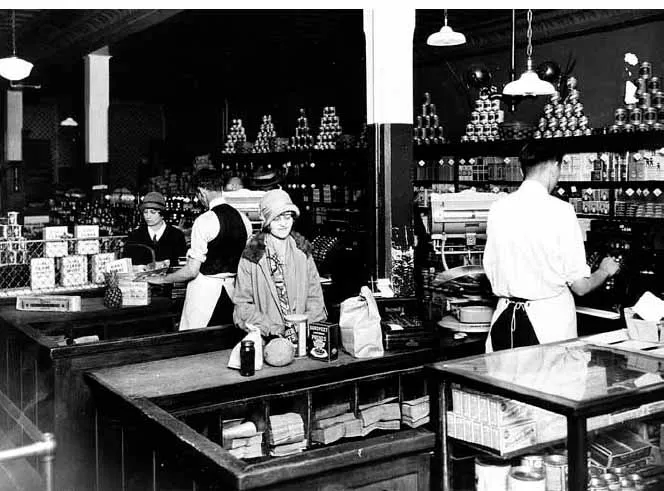

But there was more to Memphis during the twentieth century than violence and prudishness. Out of this provincial, strife-torn city came bursts of creativity that transformed the cultural landscape of the United States and much of the world. This culture of ingenuity was evident throughout the twentieth century. For example, local entrepreneur Clarence Saunders founded Piggly Wiggly grocery stores in 1916. Saunders’s self-service concept gave consumers the freedom to choose what brands of products they wanted instead of relying on the judgment of grocery store operators. Piggly Wiggly not only revolutionized how Americans shopped for food but also influenced the development of brand-name loyalty.

Founded in Memphis in 1916, Clarence Saunders’s Piggly Wiggly grocery stores revolutionized how Americans shopped for food.

Piggly Wiggly shoppers were able to choose what brands of products they wanted instead of relying on the judgment of grocery store operators.

W.C. Handy published the first blues song, the “Memphis Blues,” which transformed popular music in the twentieth century.

The Bluff City also inspired musician W.C. Handy, who composed the “Memphis Blues” in 1909, which brought attention to southern black music. In 1923, the noted singer Bessie Smith performed over radio station WMC, spreading blues music over the airwaves to Chicago and other cities of the Northeast. Memphis was a leading recording center in the 1920s and 1930s because Ellis Auditorium, built in 1925, contained soundproof rooms. Many of the major stars of blues and country music recorded in Memphis during the 1920s and 1930s.

Memphis-style creativity reached its zenith in the 1950s. In January 1950, radio announcer Sam Phillips started the Memphis Recording Service, where he recorded anyone who could afford the small fee. Like Ellis Auditorium in the 1920s and ’30s, musicians flocked to 706 Union Avenue to make inexpensive recordings. In 1951, Phillips recorded the song “Rocket 88” by Jackie Brenston, which became a big hit when released by Chess Records. The fact that he received only the initial recording fee and no other compensation for this landmark record convinced Phillips to found Sun Records in 1952. Phillips had a deep faith in music and its power to bring whites and blacks together in the segregated South. To that end, he recorded major black artists such as Rufus Thomas, the Howlin’ Wolf and B.B. King. He brought these artists to the attention of mainstream white audiences, particularly white teenagers. Phillips also recorded white artists such as Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis and, most notably, Elvis Presley. The music that Sam Phillips recorded at Sun Records remade the cultural landscape of America and arguably did weaken the bonds of segregation in the South.

The same year that Sam Phillips recorded “Rocket 88,” another Memphis businessman took his wife and five children on a driving trip to Washington, D.C. Kemmons Wilson and his family discovered that it was very difficult for large families to find clean, inexpensive accommodations while traveling. Wilson later described his trip as “the most miserable vacation…of my life.” As a result of this “miserable” experience, Wilson built a new kind of motel in 1952 on Summer Avenue, which he named Holiday Inn; it was taken from the title of a Bing Crosby film. Holiday Inns offered many motel innovations that we take for granted today, including swimming pools, ice machines, TV sets and telephones in each room. Holiday Inns also allowed children to stay for free.

Despite the significant contributions that Memphians made in revolutionizing American life, few commentators noticed. Instead, the media continued to focus almost exclusively on the more unseemly aspects of the Bluff City. This was particularly true after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered in Memphis during the 1968 Sanitation Strike. In the April 12, 1968 issue of Time magazine, Memphis was described as a “decaying Mississippi River town” and a “Southern backwater.” In the 1970s, while the rest of the South was transformed by the media into the racially tolerant, economically prosperous “Sun Belt,” Memphis remained mired in a negative image. The New York Times reported that Memphis was “a city that wants never to change” as it implemented court-ordered busing to fully integrate its public schools in January 1973. When the fire and police departments went on strike in the summer of 1978, the Wall Street Journal snidely described the Bluff City as “the Sun Belt’s dark spot.” Echoing this view, a columnist for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution wrote: “I don’t know when Memphis died, but it has not lived for years. That anarchy reigns now, that knaves and fools run wild in the streets unfettered by constraints of order and sanity, is a disconsolate epitaph to the decline of a civilized city.”

Perhaps the cruelest description of Memphis came in 1981, when a newspaper reporter from Brockton, Massachusetts, visited Memphis and afterward described it as a “hell-hole” and “the armpit of the nation.”

As the century came to a close, however, a far more nuanced portrait of the Bluff City began to emerge. In 1998, American Heritage described the city in almost mystical terms when it chose Memphis as its annual Great American Place.

For anyone who visits the nightspots of Beale Street,

who travels to Faulkner country just to the south,

eats ribs at the Rendezvous, or buys voodoo powder at Schwab’s,

the sultry mysterious Memphis that gave birth to the Blues,

to Rock ’n’ Roll, and to soul will cast its luxuriant, disturbing spell.

U.S. News and World Report was also enthralled with the city, telling its readers that “Memphis manages to preserve the diversity and pure Southern quirkiness that made it the logical birthplace of rock-and-roll.” A year later, the ABC Television Network featured Memphis prominently in its documentary series The Century, hosted by noted broadcaster Peter Jennings. The series focused on key events and personalities that shaped the twentieth century, and one of the episodes, entitled “Memphis Dreams,” chronicled the rise of Elvis Presley, the 1968 Sanitation Strike and the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

In the end, regardless of whether the Bluff City was perceived to be a “southern backwater” or a “sultry mysterious” place, the fact remains that during the twentieth century Memphis transformed the cultural landscape of the United States, and much of the world, with its rebellious creativity and innovation.

![]()

“The Beethoven of Beale Street”

The Relationship between W.C. Handy and Memphis

In 1889, sixteen-year-old William Christopher Handy of Florence, Alabama, boarded a train for an overnight visit to Memphis. Not long before, a traveling musician had regaled the young man with romantic tales of Beale Street, and he was determined to see the place for himself. Although he only stayed one night, Handy was enthralled with the city and remained so for the rest of his life. Recalling that first visit in a 1950 letter, Handy wrote: “I walked to Beale Street and in the distance saw Beale Street Baptist Church with a cupola on which John the Baptist with his arm pointed heavenward. This to me was the most inspiring site on Beale Street. Fate decreed that my life’s work would centre around the thoroughfare where the Blues was born.” Handy’s visit to the Bluff City not only, as the quote suggests, charted the course of one man’s life but also strongly influenced the direction of American popular music in the twentieth century.

Even before his brief trip to Beale Street, young Handy was fascinated with music. He bought a guitar and proclaimed that he wanted to be a musician when he grew up. “I’d rather see you in a hearse…than to hear that you had become a musician,” Handy’s preacher father boomed when he heard of his son’s desire. Despite his father’s opposition, Handy continued to pursue music whenever he could. He bought a used cornet, and when a circus arrived in Florence, Handy secretly received lessons from the troupe’s band leader. It did not take long for the young man to master his instrument, and soon he was playing with a local band. In 1896, he joined Mahara’s Minstrels, in which he played the cornet and trumpet, organized a singing quartet and wrote the arrangements. Constant travel with the minstrels exposed Handy to many types of music, which he put to good use when he later composed his own scores.

He briefly abandoned the performer’s life to teach music at Alabama A&M College, but in 1903 he was named orchestra leader for the Knights of Pythias in Clarksdale, Mississippi. During countless performances across the Mississippi Delta, Handy heard songs that were “simple declarations expressed usually in three lines and set to a kind of earth-born music that was familiar throughout the Southland half a century ago.” When the orchestra leader witnessed a blues band in the Mississippi hamlet of Cleveland being showered with coins by an enthusiastic audience, he experienced a moment of clarity. “That night a composer was born, an American composer. Those country black boys at Cleveland had taught me something…the American people wanted movement and rhythm for their money,” Handy later recalled.

Four years later, in 1907, Handy relocated to Memphis with the “earth-born music” of the Mississippi Delta still playing in his head. In between regular performances at Pee Wee’s Saloon on Beale Street, Handy composed songs based on the blues rhythms he’d heard in his travels. In 1909, Handy was hired to provide musical interludes at political rallies for mayoral candidate E.H. Crump. At one rally, he debuted a new instrumental song entitled “Mr. Crump,” which quickly became a popular tune. Crump was running as a reform candidate, promising to eradicate vice from the streets of Memphis. Many of the denizens of Beale Street took a dim view of Crump’s reform proposals, and some added derogatory lyrics to Handy’s song. Inspired by these street lyricists, Handy composed words to his composition that incorporated their scornful phrasing: “Mr. Crump won’t ’low no easy riders here…We don’t care what Mr. Crump don’t ’low: We gon’ to bar’l-house anyhow. Mr. Crump can go and catch hisself some air.” Recognizing the popularity of his tune, Handy decided that the song should be published. Writing in his autobiography, Handy explained:

But the idea of perpetuating the song in any form raised problems. To begin with, I was now embarrassed by the words. With Mr. Crump holding forth as mayor, I couldn’t get the consent of my mind to keep on telling his honor to catch hisself some air…So, in a mood of warm sentiment for the city that had been so good to me, and in memory of the nameless folk singers who had brought forth blues, I decided on a new title. “Mr. Crump,” still unpublished, became the “Memphis Blues.”

Beale Street, seen here in 1944, inspired W.C. Hand...