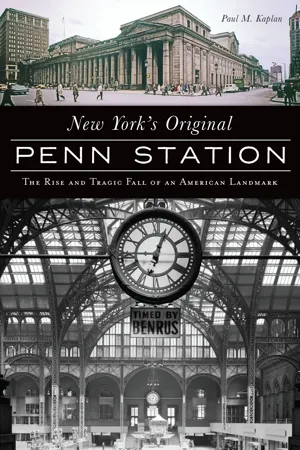

![]()

Chapter 1

THE DISCONNECTED RAILROAD JOURNEY

The Pennsylvania Railroad Corporation (PRR) had a persistent problem. It was the most extensive, busiest railway in the nation with ten thousand miles of track extending through the American heartland. But it could not connect to the country’s largest city and center of commerce. Passengers arriving from New Jersey had to disembark from the train and take a ferry over the much-trafficked Hudson River to reach Manhattan’s shores.

Passenger ferries had to share the river with cargo carrying ice, coal, corn, wheat or other goods depending on the season. “Every 10 minutes a Pennsylvania Railroad ferry headed across the Hudson River threading a gauntlet of oceangoing ships, ferries operated by other railroads, tugs, lighters, car floats of one sort or another. The congestion of watercraft on the Hudson River was becoming intolerable.”2

The ferry rides were rife with problems. They were subject to weather changes. At times, they were dangerous. From a passenger standpoint, they were uncomfortable. For time-pressed commuters, they were arduous and slow. Perhaps in previous centuries, passengers may not have expected much more. But the railroad raised their expectations.

Upon arriving on Manhattan’s shores, most passengers would be greeted with the rough-and-tumble West Street downtown. The area was not desirable. It was a noisy, confusing, hustle and bustle of crowds and merchants. The New York Tribune described the West Street waterfront neighborhood where passengers would enter in unflattering terms. It was “a waterfront as squalid and dirty and ill-smelling as that of any Oriental port lined with storage and cold-storage warehouses and large commission houses. It looked gloomy and forbidding.”3 The prominent newspaper also described the neighborhood as “a whirlpool of slime, muck, wheels, hoofs, and destruction.” Various modes of transportation competed for space on the crowded streets: express wagons, clanging trolley cars and horse-pulled carriages. Worse yet, the area was crime-ridden at night from gangs that hovered around the deserted docks.

Improving the passenger experience was undoubtedly a reason the PRR wanted to reach Manhattan’s shores by rail. But there was also a compelling business reason. The disjointed journey into Manhattan often slowed traffic. This broken journey was a problem for both passenger and freight movement, and it resulted in lost revenues.

What’s more, New York was the center of commerce for the United States—and one of the most influential cities in the world. Not being able to cross the Hudson or East River to the island of Manhattan was an affront to the PRR, the industry’s dominant railway. As the country’s most extensive railroad, it hauled more freight and transported more passengers than any competitor. “By 1900, the Pennsylvania Railroad was the largest corporation in the world. With over 100,000 employees, its operating budget was second only to the federal government’s.”4

In this era, railroads dominated the economy, trade and transportation. Jill Jonnes, the author of Conquering Gotham, explained the significance of the railroads to the country at large: “The railroads completely remade and redefined every aspect of life in America. They knit the whole country together and really created an entirely new economy. And it was a very industrialized economy, and it was a very urbanized economy.”5

The expansion of railroads ignited the economy. Suddenly, goods could be transported more quickly and more efficiently. Railroads reduced transportation costs markedly. Historian Martin Albro proclaimed, “In all of the human past, no event has so swiftly and profoundly changed the basic order of things as had the coming of the railroad.”6 Yet, as Albro pointed out, the changes were also catastrophic, as the carnage it produced in people and property from accidents and collateral damage was unprecedented.

With this lofty plan to knit the country together, the Pennsylvania Railroad attempted to connect to New York’s shores for more than thirty years. But the surrounding rivers would not be tamed. Some engineers suggested a large-scale bridge. However, the price tag was a startling $50 million (about $1.3 billion in present dollars). Its length would need to be about twice that of the Brooklyn Bridge. Since most trains were steam locomotives, going through long, arduous tunnels under the Hudson River seemed impossible, if not downright dangerous.

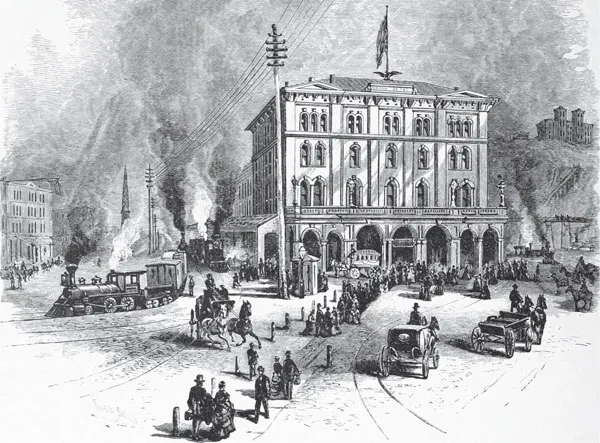

The Pennsylvania Railroad Corporation in 1875 in Pennsylvania would become the largest and most influential company in the United States. Wikimedia Commons.

VANDERBILT’S RAILROAD EMPIRE

In 1901, there were few significant means of connecting the island of Manhattan to its surrounding areas. There was the majestic and gracious Brooklyn Bridge connecting Manhattan and Brooklyn. That was the only East River crossing. The next one, the Williamsburg Bridge, opened in 1903. There was only one train line, called the New York Central Railroad, owned by the robber barron William Vanderbilt, one of the world’s wealthiest men and the descendant of the famed Cornelius Vanderbilt. This railroad had the profound competitive advantage of coming into Manhattan when others could not. Its trains came from upstate New York and ran through the east bank of the Hudson, near the Harlem River and into Manhattan. The New York Central had bridges over the Harlem River at the head of Park Avenue and Spuyten Duyvil, their current locations. There were some road bridges over the Harlem River, including the oldest at Kingsbridge. There was also the aqueduct at the High Bridge, built in 1848, which served as a link in the Croton aqueduct bringing fresh water into Manhattan from the Bronx.

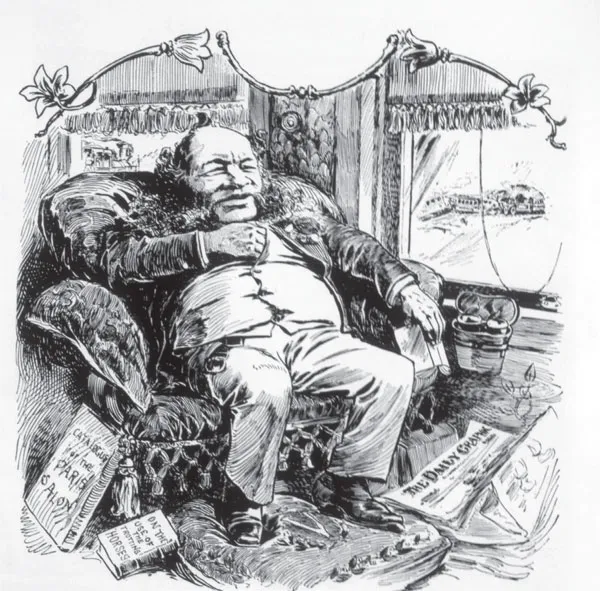

Railroad mogul William Henry Vanderbilt depicted saying, “The public be damned” in a New York Daily Graphic political cartoon, 1882. Shutterstock.

The only functional railroad line during this period was William Vanderbilt’s New York Central. William was not known for his concern for passengers. History has shown him as ruthless and greedy. He is said to have remarked, “Let the public be damned.” Though not customer friendly, he was the PRR’s fiercest competitor. He had succeeded in connecting his railway to Manhattan, a feat the Pennsylvania Railroad had been trying for decades.

One cannot overstate the influence of these railroads at the time. Their leaders wielded disproportionate power and control. They were the hub of the economy, perhaps like Wall Street houses and hedge funds are today. James Bryce, a British politician, observed of this American phenomenon that “[t]hese railway kings are among the greatest men, perhaps I may say are the greatest men in America. They have more power, than perhaps anyone in political life, except the President and Speaker.”7

For decades, railroads besides the PRR longed to enter Manhattan. They wanted to take on Vanderbilt’s empire. But like the PRR, they also wanted to provide the convenience for passengers, saving them the huge hassles of taking the ferries across the Hudson into the hustle and bustle of rough New York neighborhoods.

ALEXANDER CASSATT: THE RAILROAD INNOVATOR

Few had thought of this challenge more than Alexander Cassatt, the former first vice-president of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Many thought of him as the most brilliant railroad official in the United States.8 In pondering the conundrum of his large railway’s inability to reach Manhattan’s shores, he remarked to a fellow engineer, “I have never been able to reconcile myself to the idea that a railroad system like the Pennsylvania should be prevented from entering the most important and populous city in the country by a river less than a mile wide.”9

In the early 1880s, the promising forty-two-year-old railroad executive had unexpectedly resigned from his post. This announcement came as a big surprise not only to his company but also to the industry at large. Cassatt was not leaving for another role in a different company. He resigned to enjoy an early retirement. Some surmised that Cassatt was irked at being passed over as the railway’s president in 1880 by George P. Roberts. More likely, though, Cassatt desired a life free of the daily concerns of an executive.

The once promising railroad executive signed his letter of resignation. The letter noted that he “wanted more time at my [his] disposal than anyone occupying so responsible a position in railroad management can command.”10

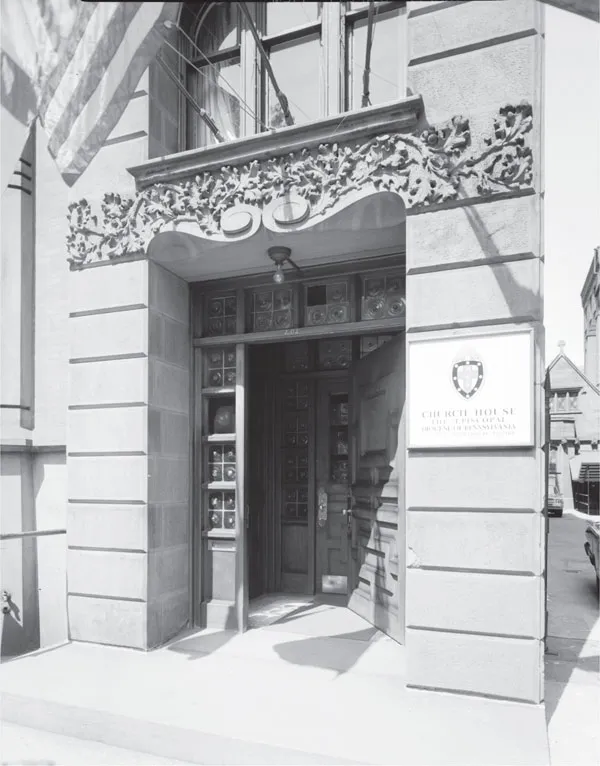

An 1850s townhouse in Philadelphia that served as the home of Alexander J. Cassatt; his sister, painter Mary Cassatt; and Fairman Rogers, a prominent scientist and civil engineering professor. The house was demolished in 1972. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs.

Portrait of Alexander Cassatt, one of the early visionaries of New York’s Penn Station and tunnels underneath the Hudson and East Rivers. Shutterstock.

Born into a wealthy family, he had the means to retire early. His father made his fortune in banking and real estate in Pennsylvania’s two major cities, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. Not uncommon of wealthy families at the time, the Cassatts spent considerable time in Europe when Alexander was young. Who could have known the influence Europe would have on both Alexander and his sister, Mary. She would ultimately become an expatriate in Paris and one of the most influential impressionist painters. She was and is famous for painting domestic scenes, such as a mother bathing her child. The U.S. Post Office later honored her life with a commemorative stamp.

Tutored in French and German, Alexander Cassatt preferred the hard sciences. He studied at the well-known Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in upstate New York. Upon graduating, his career collided with the outbreak of the Civil War. He began his career at a railway in Georgia but soon moved north as the war broke out. Though from an affluent family, Cassatt worked his way up the corporate ladder at the Pennsylvania Railroad. He joined as a surveyor’s assistant, carrying the leveling rod for a low wage. For a few years, Cassatt roughed through treacherous terrain, surveying the land in desolate places for the railroad.

Commemorative stamp of famed impressionist artist Mary Cassatt, known for painting domestic scenes. Shutterstock.

He was a hard worker, but more than that, he understood accounting and financials. His superiors took notice. Patricia Davis’s End of the Line: Alexander Cassatt and the Pennsylvania Railroad described an encounter.11 His supervisor asked Cassatt a series of accounting questions. “Cassatt reeled off the figures. Scott was amazed at his memory. He wondered how Cassatt knew these accounting numbers by heart. ‘Oh, I think it’s a pretty good scheme to go through the books every few days so that if anything happened to the bookkeeping department, I might not be left in the lurch.’” Other superiors noted that Cassatt exhibited a “natural talent for machinery and when riding over the road he would almost invariably be found handling the locomotive, while the engineer rested.”12

The young employee soon advanced up the ranks. He helped the railroad expand in the Midwest. Unlike most railroad employees, who were “doers,” Cassatt stood out for his unconventional and, at times, controversial thinking. He challenged superiors to rethink key decisions. He influenced the company to adopt the air brake. Produced by George Westinghouse, this air break allowed heavier trains to run more safely. It was subsequently used in the railway’s advertising: “Speed, Comfort, and Safety Guaranteed by Steel Rails, Iron Bridges, Stone Ballast, Double Track, Westinghouse Air Breaks, and the Most Improved Equipment.”

As Cassatt’s career was taking off, so was his love life. He was smitten by Lois Buchanan, the daughter of an Episcopal minister. She was also the niece of ex-president James Buchanan. He was considered one of the nation’s worst presidents, but his niece was still proud. The engineer showed his poetic side when writing her, “I see you now as you sat at the table yesterday evening—your face and hair illuminated into the most beautiful color—the roses in the bouquet could not vie with the beauty of your complexion and your eyes—the brightest in the world—never was there a more engaging picture.”13

In an industry marked by corruption and back-room deals, Cassatt stood apart. He resented the bullying he saw take place. He felt uneasy about a secret deal his company had struck with Standard Oil. As an act of appeasement to Rockefeller and his Standard Oil, Pennsylvania Railroad president Thomas Scott offered secret rebates. It was a two-sided giveaway. Scott offered Rockefeller a secret rebate not only on Standard Oil’s shipments but also for shipments of its competitors. This ploy tipped the playing field for Standard Oil and swelled its profits. Consequently, it paved the way f...