![]()

1 THE BASICS

GETTING THERE

OVERLAND

So you want to go to the Greek Olympic Games? You may be disconcerted to learn that getting there is far from straight-forward. This may be the premier event in the Greek sporting calendar, but it takes place in a remote rural backwater located a good distance from any major thoroughfare.

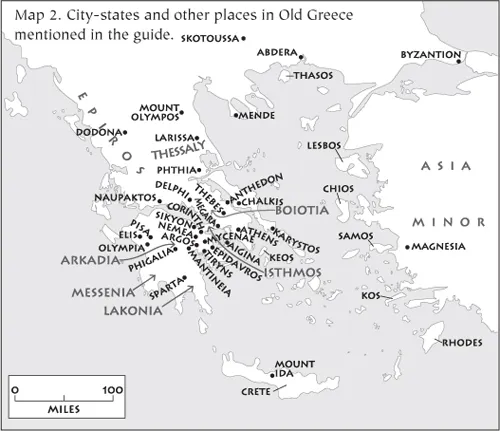

The Games are hosted by the city of Elis, a minor state tucked away in the northwestern Peloponnese, and Olympia itself, the sacred site where the contests are held, lies some thirty-six miles to the southeast. This means the site is a long way from all the major Greek cities. If you are coming from Central Greece, Athens is 120 miles distant, Thebes 110; if from within the Peloponnese, Corinth is seventy-five miles away, Argos and Sparta both sixty. (These distances are approximations: there are no accurate long-distance measurements in ancient Greece.)

The actual travelling distance is much longer, as few of the roads are straight, and many wind through hill country. The ‘roads’, moreover, are atrocious – just rough tracks – which makes travelling in any sort of vehicle slow, uncomfortable and expensive. Carts drawn by mules, oxen or horses (in ascending order of cost) are available for hire, but usually only for short distances across local plains; you will then have to walk the hill-country and hire again on the far side. An alternative, especially if you are heavily laden with baggage, is to hire a donkey or mule, which may take you the whole way. The problem – apart from the expense – will be finding one, with tens of thousands of people on the move. Anyone on a tight budget is likely to find themselves walking. You can certainly assume that those passing you on the road on horseback or in horse-drawn chariot are rich.

The Greeks are used to walking. Life is simple, most people relatively poor, and the terrain arduous, so it is often the best way. People tend to reckon the distances between places in walking-time. The workers in the Peiraieus Harbour consider a trip to Athens and back, around nine miles in total, an easy day. An army is expected to march between fifteen and seventeen miles in a day. The thirty-six mile procession from Elis to Olympia at the start of the Games takes two days. If you are a good walker, you can probably manage fifteen to twenty miles a day, even on cross-country tracks.1

Is it safe? This is the question that everyone asks. Greece is divided into some 1,000 independent city-states. Many are bitter rivals, warfare is endemic, and it is quite common for there to be several local wars being waged in different parts of Greece at the same time. To give an idea, over the last century Athens has been at war three years out of every four.

Despite this, travelling across Greece to the Olympics is relatively safe. Because Greek armies are citizen-militias made up of ordinary farmers, military campaigns are usually restricted to spring and summer – that is, between sowing and harvest. Most campaigns do not result in pitched battle, and if they do, it is often by pre-arrangement between belligerents. Even when territory is being laid waste, with crops cut down and buildings demolished, civilians are rarely targeted, and religious sanctuaries hardly ever plundered.2 Moreover, anyone en route to the Olympics is considered a pilgrim, under divine protection, such that any kind of hostility or violence amounts to violation of a strict religious taboo.

It is as well to know this, since travelling any distance overland will involve crossing numerous borders, and in some cases passing through actual war zones. The borders are unmarked and unguarded. Passports do not exist. But during the Games, the land is under a Panhellenic ‘Sacred Truce’, which effectively guarantees safe passage through the territory of any state to all those going to or coming from Olympia. The Sacred Truce does not – as some people naïvely imagine – mean that the fighting stops. Rather, it allows the Games to take place despite the fighting, as they did throughout the long and bitter Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta in the late fifth century BC.

Even so, you should take care. State authorities maintain order inside city precincts, but they do not police the local countryside. Brigands are not unknown in the more remote areas, and many live not only outside the laws of men, but also without regard for the precepts of the gods. There are places in Greece where the protective mantle of the Sacred Truce is somewhat ragged.3

BY SEA

The alternative is to go by sea. Due to the parlous state of the roads and the expense of overland travel, water transport, wherever possible, is always first choice in ancient Greece. An ox will consume the equivalent of its own load in a month of haulage work; over the same period, the crew of a ship will consume only a tiny fraction of their cargo.4

Olympia is only nine miles from the sea, and the River Alpheios, which runs past the site, is navigable for light craft. Even if you are coming from other parts of mainland Greece, it may be preferable to go around the coast by ship than to travel overland. But if you are coming from any of the islands or the colonies, there is, of course, no choice but to travel at least part of the way by sea.

There are no passenger ferries. All Greek sailing ships are designed to take cargo. They are small, short, broad-beamed, wind-dependent, and vulnerable in a storm. Average speed in favourable conditions is around five knots. On the other hand, the crew is small and space ample, so the ship can carry everything it needs, and once at sea you may not need to put into port until you reach your destination.

1. An ancient merchantman. Going to the Olympics by sea usually means perching on top of the cargo.

You will see large rowing vessels, which are much faster, cruising at seven or eight knots, and capable of up to thirteen knots in short bursts. But these are triremes – warships – built for speed and power rather than ocean-going voyages. The whole of the inside of the hull is taken up with wooden benches to accommodate 170 rowers, with minimal space for carrying water and provisions, and none at all for passengers. You cannot get to Olympia on a warship. And you would not want to. A trireme is likely to take on water and sink if a storm gets up. The journey would take longer because the vessel has to beach every night. And the stench of 170 heaving, sweating, tight-packed bodies inside the hull during high summer can be overpowering.

That is not to say that conditions on the trading vessels employed as ferries during the Games are pleasant. Ship-owners are liable to charge extortionate prices for nothing more than a perch on top of the cargo. For anyone on a tight budget, it will almost certainly be a matter of creating your own improvised berth, either in the gloom of the hold or on the open deck above, taking a chance on the personal hygiene of whoever pitches up as proximate neighbours.

Once aboard and on the move, there is a premium on endurance, patience and tolerance. Assuming favourable winds all the way (unlikely), the voyage takes at least a day from Corinth, two from Athens (including being hauled across the Isthmos), and five from Syracuse in eastern Sicily. From the most distant Greek cities – Ampurias in Spain, or Phasis on the Caucasus side of the Black Sea – the journey can take a fortnight.

The only way to cut the journey time would be to go direct, across open sea, but it is virtually impossible to persuade a Greek skipper to risk this, even in the fairly storm-free summer months. Hugging the coast is dangerous enough: a sudden squall can drive any sort of Greek vessel onto the rocks. Nervous passengers will spend much of the voyage praying to Poseidon for deliverance and pouring libations over the side. Of course, if coming from Naukratis in Egypt or Kyrene in Libya, there is no choice but to cross the Mediterranean. The libations will then be more generous.

So, going by sea, you are in for the long haul. You will be lucky if the ship is more than twenty metres long. It will have hurdlework above the gunwales designed to increase capacity, and the skipper can be guaranteed to have packed the vessel to maximise profit, perhaps taking on a mix of passengers and cargo (there being a captive market at the destination). With the crush onboard and the swaying of the vessel, sleep is virtually impossible. Expect to arrive at Olympia exhausted.5

Poor transport links are the key reason the Olympics tend to be a Western Greek event, with disproportionate numbers of athletes and spectators coming from southern Italy, Sicily and the Adriatic. The Olympics is one of four top festivals – known as the ‘crown’ games – but they are the least accessible. The Isthmian and Nemean Games, both on the opposite side of the Peloponnese and easily reached by sea, tend to attract Eastern Greeks from the island and coastal cities of the Aegean, while the Pythian Games at Delphi are best supported from Central and Northern Greece. Nonetheless, despite occupying the worst location, Olympia has achieved an unchallengeable position as Greece's premier sports festival (see pp. 126ff).6

When you finally arrive, Olympia, nestled in a hollow surrounded by gentle hills, can look idyllic. The leisurely River Alpheios runs in multiple streams through a wide flood-plain on the southern edge of the site, while its narrow tributary, the Kladeos, runs beside the western boundary. The northern side is dominated by a steep-sided conical peak, the Hill of Kronos. The whole region is rich with cornfields, vineyards, olive groves and cattle pasture. Whether you have come over the rugged mountain passes of Arkadia or have island-hopped by sea, Olympia may seem a good place to have come to.7

But you may not have noticed, being wholly preoccupied with the traffic jam and the crowds, as hundreds of carts and chariots, thousands of mules and horses, and tens of thousands of people nudge their way into the Olympic Village sprawling along the north bank of the Alpheios. At least there is no ticket barrier – the Olympic Games are free. But that is not to say they are cheap and easy. You will need to have come prepared. This may be the biggest religious and sporting festival in ancient Greece. There may be 100,000 spectators staying for a week. But there are no facilities of any kind. Everyone has to fend for themselves.

ALPHEIOS AND ARETHUSA

Western Greeks, especially Syracusans, think of a visit to Olympia as a homecoming. The link between the western Peloponnese and Sicily is mythologised in the story of Alpheios and Arethusa.

Arethusa was a nymph, huntress, and follower of Artemis, goddess of the wild woods and virgin huntress. One summer's day, hot and tired from the hunt, she came upon the River Alpheios, running clear and cool, shaded by poplars and willows along the bank. She stripped off and dived in.

Looking up from the depths was the river god. Aroused by the beauty of the naked nymph swimming above, Alpheios surged upwards in a whirl of foaming water, groping towards Arethusa.

S...