- 228 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

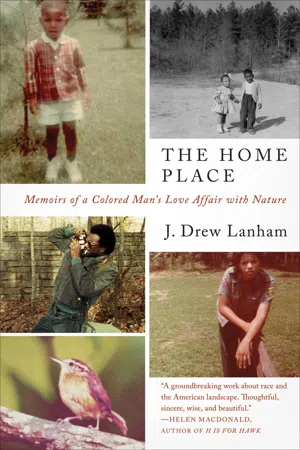

"A groundbreaking work about race and the American landscape, and a deep meditation on nature…wise and beautiful."—Helen Macdonald, author of

H is for Hawk

A Foreword Reviews Best Book of the Year and Nautilus Silver Award Winner

In me, there is the red of miry clay, the brown of spring floods, the gold of ripening tobacco. All of these hues are me; I am, in the deepest sense, colored.

Dating back to slavery, Edgefield County, South Carolina—a place "easy to pass by on the way somewhere else"—has been home to generations of Lanhams. In The Home Place, readers meet these extraordinary people, including Drew himself, who over the course of the 1970s falls in love with the natural world around him. As his passion takes flight, however, he begins to ask what it means to be "the rare bird, the oddity."

By turns angry, funny, elegiac, and heartbreaking, The Home Place is a meditation on nature and belonging by an ornithologist and professor of ecology, at once a deeply moving memoir and riveting exploration of the contradictions of black identity in the rural South—and in America today.

"When you're done with The Home Place, it won't be done with you. Its wonders will linger like everything luminous."— Star Tribune

"A lyrical story about the power of the wild…synthesizes his own family history, geography, nature, and race into a compelling argument for conservation and resilience."— National Geographic

A Foreword Reviews Best Book of the Year and Nautilus Silver Award Winner

In me, there is the red of miry clay, the brown of spring floods, the gold of ripening tobacco. All of these hues are me; I am, in the deepest sense, colored.

Dating back to slavery, Edgefield County, South Carolina—a place "easy to pass by on the way somewhere else"—has been home to generations of Lanhams. In The Home Place, readers meet these extraordinary people, including Drew himself, who over the course of the 1970s falls in love with the natural world around him. As his passion takes flight, however, he begins to ask what it means to be "the rare bird, the oddity."

By turns angry, funny, elegiac, and heartbreaking, The Home Place is a meditation on nature and belonging by an ornithologist and professor of ecology, at once a deeply moving memoir and riveting exploration of the contradictions of black identity in the rural South—and in America today.

"When you're done with The Home Place, it won't be done with you. Its wonders will linger like everything luminous."— Star Tribune

"A lyrical story about the power of the wild…synthesizes his own family history, geography, nature, and race into a compelling argument for conservation and resilience."— National Geographic

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Home Place by J. Drew Lanham in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Flock

The Home Place

Home is a place we all must find, child. It’s not just a place where you eat or sleep. Home is knowing.

IT WAS HOME: EDGEFIELD, SOUTH CAROLINA, A SMALL COUNTY on the western edge of the Palmetto State. The county’s name is well earned. With its western flank tucked tightly against the banks of the once mighty but now dammed Savannah River, on the edge ecologically between Upstate and the Lowcountry, Edgefield contains an incredible natural wealth of mountain, piedmont, and coastal plain.

Among South Carolina’s forty-six counties, Edgefield is not large, covering only some five hundred square miles. The political boundaries drawn by human hands give it the appearance on maps of a cartoonish chicken’s head, its squared-off comb to the north, huge triangular beak pointing east toward the Atlantic, and shortened neck jutting to the southwest. Nature sketched the westward boundary where Stevens and Turkey Creeks skirt along the raggedy rear of the bird’s head and form the long border with McCormick County. Surrounded by piedmont places to the north—Greenwood, McCormick, and Saluda—and Aiken, an upper–coastal plain county to the south, Edgefield is a transition zone, with each of the imaginary poultry’s portions harboring ecological treasures. Growing up near the bird’s scrawny neck—in the south-central part of the county, only a few miles from the Savannah River and an equidistant stone’s throw from the sprawl of North Augusta and the sleepy town of Edgefield—I was privy to the beauty and diversity of a spot most ignore.

Edgefield is many places rolled into one. With the exception of saltwater and high peaks, there’s not much that can’t be found there. Droughty sand holds onto remnant stands of longleaf pine and stunted turkey oaks in the southern and eastern extremes where the upper coastal plain peters out. In the soggy bottoms along many of the rivers and creeks, rich alluvial soils grow splotchy-barked sycamores and warty hackberries to girths so big that two large men joined hand to hand couldn’t reach around them. A few buttressed bald cypresses draped in Spanish moss sit in tea-stained sloughs. Between the extremes of wet and dry, high and low, even the sticky clay nourishes a surprising variety of hardwoods; slow-growing upland oaks and tight-grained, tough-as-nail hickories grow alongside fast-rising tulip poplars and opportunistic sweetgum. In the understory redbud and dogwood trees sit in the shade of the dominants, blooming briefly in spring before the canopy closes with green overhead.

Loblolly pine, the sylvan savior of southern soil, is everywhere. A tree that grows best in moist bottomlands, it climbed the hills out of the swamps with some help from human hands and colonized eroding lands. Loblolly is a fast grower that stretches tall and mostly straight in forests that have been touched occasionally by fire and saw. In open stands, where the widely spaced trees can grow with broom sedge and Indian grass waving underneath, bobwhite quail, Bachman’s sparrows, and a bevy of other wildlife can find a place to call home. But where flames and forestry have been excluded, spindly trees fight with one another for sun and soil and will grow thick like the hair on a dog’s back. In those impenetrable stands white-tailed deer find secure bedrooms but little else dwells.

Most of the county sits in the lower piedmont. This Midlands province stretches like a belt, canted southwest to northeast, across the state’s thickened waist. Torn apart first by agriculture, then by unbridled development, the fragmented middle sits between the more spectacular coastal plain and the mountains.

Coastward, you’ll find black-water swamps, brackish marshes, and disappearing cathedrals of longleaf pine that hide species both common and rare. Red-cockaded woodpeckers, diamondback rattlesnakes, and gopher tortoises hang on in some places where the longleaf persists. Painted buntings splash color across the coastal scrub and alligators bellow in rebounded numbers among wading wood storks.

Northward, the modest Southern Appalachians are bounded by the escarpment the Cherokee called the “Blue Wall.” The place not so long ago called the “Dark Corner” still stirs the imagination as gorges rush wild and cool with white water and a few persistent brook trout linger in hidden pools. Moist coves crowded with canopies of hardwoods sit below and among a few granite monoliths that folks flock to see. Within the memory of a three-hundred-year-old poplar this was the backcountry: a wilderness with “panthers,” elk, and wood bison roaming canebrakes and rhododendron hells. Now peregrine falcons and common ravens patrol the skies while black bears grow fat on Allegheny blackberries and the easy pickings in exclusive gated communities.

Sitting on either flank of the broad and broken piedmont, the mountains and the coast harbor opportunities for wildness that the worn-out region in between has lost to easy progress. But Edgefield County, caught in the middle of all the apparent mediocrity of the piedmont, is yet a hidden gem, a source of biodiversity that is easy to pass by on the way to somewhere else.

There are still priceless places where nature hangs on by tooth, talon, and tendril. Most of Edgefield is rural. There are trees everywhere, though most of them reside on private lands, where there is a priority set on pines over pavement. Significant portions of the Sumter National Forest’s Long Cane Ranger District lie in the county, providing public access to places where nature is the first consideration. Farming and forestry provide diversity within the tree-dominated matrix. I grew up in the southwestern outreaches of the county, in a ragged, two-hundred-acre Forest Service inholding. From heaven—or from a high-flying bird’s viewpoint—I imagine it looked like a hole punched into the Long Cane Ranger District. That gap in the wildness was my Home Place.

In the 1970s, when wild turkeys were still trying to establish a clawhold everywhere else, they were common enough on the Home Place as to be almost unremarkable. I’d often surprise a flock as they fed in the bottomland pasture. Most of the big birds would take off running for the nearest wood’s edge, but a couple of gobblers always lifted off, powerfully clearing the tree line while cackling loudly at my intrusion.

Like the wild turkeys, deer weren’t really common in the wider world. But whitetails were abundant in the woods and fields of the Home Place. To Daddy, they were pests. Handsome in their foxy red coats, the deer claimed our bean fields as their own in the summer. They seemed to know that there was security in that season, with worries of hidden hunters forgotten until fall.

Daddy put many of the Home Place acres to work growing produce. Watermelon, cantaloupe, butter beans, purple-hull peas, and an array of other crops grew fast and flavorful on the bottomland terraces and sandy soil up on the hills. Tons of melons and hundreds of bushels of beans were the product of his and Mama’s hard work. The bounty wasn’t just for us, though. Daddy would load up his truck with the fresh vegetables and sell them to city and suburban folks who craved the flavor of locally grown foods not found in grocery stores. The money was an important supplement to the paltry pay he and Mama made as schoolteachers.

The investment in the crops—the plowing, planting, and fertilizing—would all be for naught, though, if the four-legged foraging machines had their way. The garden’s only chance at survival was an eight-foot-high electric fence and a phalanx of scarecrows draped in Daddy’s sweatiest, smelliest clothes. Should the fence fail and the deer’s noses unriddle the scarecrow ruse, the last line of defense was an old British Enfield .303 rifle. Daddy would sit on the roof and try to pick off one or two of the deer but he was seldom successful. Even with his constant attention to defending the garden he’d often find a sizable portion of the new crop gone overnight, the tender seedlings neatly nipped and ruminating in the belly of a whitetail that had figured out how to breach the gauntlet while we slept.

Knowing that the Home Place was surrounded by the deer heaven of the National Forest and that our fields and gardens were open buffets in the midst of it all, a couple of Daddy’s teacher friends—Mr. Sharpe and Mr. Ferguson—asked to hunt the property. Beyond the rooftop plinking Daddy didn’t deer hunt, but he believed that any pressure exerted on the bean eaters couldn’t hurt. He said yes. The two white men became the only people I remember Daddy ever trusting to hunt on the Home Place, free to roam the property and exact the revenge that my father couldn’t. Mr. Sharpe and Mr. Ferguson showed up on Saturday mornings in fall dressed in camouflage and carrying bows or rifles. They sought the whitetails with a dawn-to-dusk fervor, arriving early and leaving late. What did they do out there all day? Where did they go? It was puzzling to see the extraordinary lengths they took—getting up before the sun did and dressing like trees and bushes—just to pursue animals that grazed casually, like so many slender brown cattle, right in our backyard. It seemed to me the hunters were making something that should’ve been easy hard. But while I don’t remember ever seeing any fruits of their labors, they kept coming back and seemed happy just to be “out there.”

Beyond the white-tailed deer and the wild turkeys, wildlife was everywhere. In every natural nook and cranny—a stump hole, a dry creek bed, or a burrow in the ground—there was something furred, feathered, finned, or scaled that scurried, swam, or flew. I was amazed by it all. Curiosity grew as I explored and learned the signs of the wild souls I seldom actually saw: the delicate doglike trace of a fox; the handlike pawprints of raccoons and opossums; mysterious feathers that had floated to earth, gifts from unknown birds.

I craved knowledge about the wildlife that lived around us. I read every book I could about the creatures that shared the Home Place kingdom with me. I pored over encyclopedias and piled up library fines. Field guides were treasure troves of information: pictures stacked side by side with brief descriptions of what, where, and when. I went back outdoors, where I walked, stalked, and waited to see as many wild things as I could. I collected tadpoles to watch them grow into froglets; I caught butterflies and gazed into their thousand-lensed eyes. Birds were everywhere and as I learned to identify them by sight their songs sunk into my psyche, too. Nature was often the first and last thing on my mind, morning to night.

An April morning full of birdsong and the distant rumblings of gobbling longbeards was life in stereo. Bobwhite quail had conversations with one another from weedy ditches and thorny thickets. On my rambles I would usually flush a covey or two. The birds exploded from blackberry brambles, flying scattershot in every direction with wings a-whirring, to find refuge elsewhere. The sudden flurry never failed to push my pulse to pounding. Within a few minutes the reassembly calls—Pearlie! Pearlie!—drifted across the pasture to bring the clan back together again. On warm summer nights, barred owls boomed their eerie calls and cackles back and forth across the creek bottom as the numbing chants of whip-poor-wills and choruses of katydids and crickets lulled me to sleep.

Today, Edgefield is still a rich refuge for wild things. Most of them don’t attract the attention that deer and turkeys do. Hand-standing spotted skunks secret themselves in hedgerows and old fields. Webster’s salamanders hide in the litter of the forest floor. Christmas darters, Carolina heelsplitters, yellow lampmussels, and eastern creekshells won’t win any contests for charisma but the decorative little fish and trio of freshwater mussels survive in Edgefield’s creeks and not many other places. Many rare plants are found there, too. These rooted and leafed things are more often than not overlooked even though their lyrical names demand attention: adder’s tongue, streambank mock orange, shoals spider-lily, yellow sunnybell, Oglethorpe oak, eared goldenrod, Carolina birds-in-a-nest, small skullcap, and enchanter’s nightshade.

Edgefield has been less welcoming of—and less of a refuge for—human diversity. Under regressive and racist governors who fostered and promoted policies aimed squarely at exclusion and violence, the power base in Edgefield kept things stuck in a state of antebellum stagnation, separate and nowhere near equal. While the South has long laid claim to a culture that values manners, loyalty, honor, and a slower pace of living, there are other, less admirable traits that ooze out from between the niceties. A heaping of hypocrisy is often served alongside the southern hospitality. Double standards are as common as ragweed and persistent as kudzu across the region. The “good old days” that some pine for weren’t the best for all of us. But Edgefield was still my refuge, primarily because it was and is a sanctuary for creatures that aren’t subject to the prejudices of men.

My memory continues to run like a rabbit around the times spent in the small piedmont place I called home. It weaves and winds through woods and wetlands to reconnect me to my nature-loving roots. That pleasant wandering is reason enough for remembering—and returning—home.

A rusting, dented black mailbox teetering atop a decaying post marked the spot: Route 1, Box 29, Republican Road. Driving west you bore left at the mailbox, onto the dusty dirt road where the county had abandoned regular maintenance to chance and persistent complaints. If you stayed straight on that road for about a quarter of a mile, you’d see a brick house, tinted somewhere between orange and red, the hue of sun-faded clay. The Ranch was a typical 1970s dwelling, nothing spectacular, but mostly modern. It was comfortable and a place Daddy and Mama had worked hard to build. It had been a much smaller house until my parents bought an old army barracks and attached it to the little four-room affair that had been the Lanham abode. They encased the new addition in these clay-colored bricks, added a touch of distinction with white columns on the front porch, and called it home.

The porch looked out over a yard Mama had tried to cover with a slow-growing patch of carpetlike Zoysia grass. But it never lived up to her expectations, and weeds and Bermuda grass had to suffice for lawn. Behind the Ranch a huge hay shed sheltered food for the cattle, Daddy’s farm equipment, and almost everything else he thought might be of some future use. There was a chicken coop in the corner of the shed, and on the far side and out of sight (but not smell) a pigpen.

All of it—the Ranch, the hay shed with its tacked-on animal pens—was surrounded by nature. Well-tended gardens, crop fields, and rolling pastures buffered the Home Place from the government timberland. There was even a wetland of sorts, which in later years I would learn was really an open cesspool—the Ranch’s own homemade sewage system.

The homestead was also buffered from the outside world. Mama and Daddy were progressive thirtysomethings who’d come through the 1960s civil rights movement. They were still overcoming discrimination but saw a way to provide better for all of us, improving and enlarging their condition. Inside the Ranch there were the decorative signs of 1970s progress: faux-wood paneling and sculpted carpeting in gaudy colors. My big brother, Jock; older sister, Julia (“Bug”); and little sister, Jennifer, all grew up there. For me, though, it was mostly a part-time home. A good portion of my life up until I was fifteen was spent at the other, less-than-modern house that sat across the pasture.

That house—the Ramshackle—was down another road in both space and time. My grandmother Mamatha’s place was everything the brick Ranch wasn’t. It had a rusting (and leaky) tin roof, six tiny rooms, and an exterior of brittle, white tiles that were loose or missing in places. The house had a snaggletoothed look where the black tar paper showed through the gapped tile teeth. The porch roof had a ragged hole where she’d shot blindly one night at a hooting owl she claimed was a bad omen.

The yard was Mamatha’s pride and joy. She would sit on the wood-planked front porch on warm spring days, admiring her green-thumbed handiwork. Over her five or six decades...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Me: An Introduction

- FLOCK

- FLEDGLING

- FLIGHT

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author