eBook - ePub

Mind Without Fear

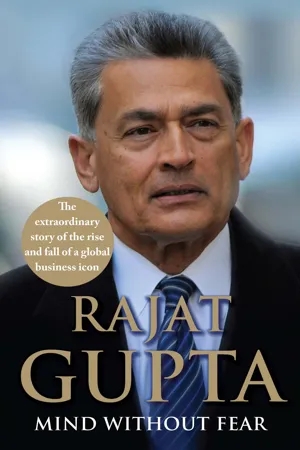

The Extraordinary Story of the Rise and Fall of a Global Business Icon

- 354 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"

A propulsive narrative filled with boldfaced names from business and politics. At times, it is a dishy score settler."—

The New York Times

For nine years, Rajat Gupta led McKinsey & Co.—the first foreign-born person to head the world's most influential management consultancy. He was also the driving force behind major initiatives such as the Indian School of Business and the Public Health Foundation of India. A globally respected figure, he sat on the boards of distinguished philanthropic institutions such as the Gates Foundation and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, and corporations, including Goldman Sachs, American Airlines, and Procter & Gamble.

In 2011, to the shock of the international business community, Gupta was arrested and charged with insider trading. Against the backdrop of public rage and recrimination that followed the financial crisis, he was found guilty and sentenced to two years in jail. Throughout his trial and imprisonment, Gupta has fought the charges and maintains his innocence to this day.

In these pages, Gupta recalls his unlikely rise from orphan to immigrant to international icon as well as his dramatic fall from grace. He writes movingly about his childhood losses, reflects on the challenges he faced as a student and young executive in the United States, and offers a rare inside glimpse into the elite and secretive culture of McKinsey, "the Firm." And for the first time, he tells his side of the story in the scandal that destroyed his career and reputation. Candid, compelling, and poignant, Gupta's memoir is much more than a courtroom drama; it is an extraordinary tale of human resilience and personal growth.

For nine years, Rajat Gupta led McKinsey & Co.—the first foreign-born person to head the world's most influential management consultancy. He was also the driving force behind major initiatives such as the Indian School of Business and the Public Health Foundation of India. A globally respected figure, he sat on the boards of distinguished philanthropic institutions such as the Gates Foundation and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, and corporations, including Goldman Sachs, American Airlines, and Procter & Gamble.

In 2011, to the shock of the international business community, Gupta was arrested and charged with insider trading. Against the backdrop of public rage and recrimination that followed the financial crisis, he was found guilty and sentenced to two years in jail. Throughout his trial and imprisonment, Gupta has fought the charges and maintains his innocence to this day.

In these pages, Gupta recalls his unlikely rise from orphan to immigrant to international icon as well as his dramatic fall from grace. He writes movingly about his childhood losses, reflects on the challenges he faced as a student and young executive in the United States, and offers a rare inside glimpse into the elite and secretive culture of McKinsey, "the Firm." And for the first time, he tells his side of the story in the scandal that destroyed his career and reputation. Candid, compelling, and poignant, Gupta's memoir is much more than a courtroom drama; it is an extraordinary tale of human resilience and personal growth.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mind Without Fear by Rajat Gupta in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Crisis

O Krishna, drive my chariot between the two armies.

I want to see those who desire to fight with me.

With whom will this battle be fought?

—Bhagavad Gita, 1:21–22

1

Solitary

Let me not beg for the stilling of my pain,

but for the heart to conquer it….

Let me not crave in anxious fear to be saved,

but hope for the patience to win my freedom.

—Rabindranath Tagore, Fruit-Gathering, 79

FMC Devens correctional facility, Massachusetts, October 2014

Four concrete walls and a cold concrete floor. One small window but not enough light to read. A steel door with a grimy plastic window and a small slot in the center, locked shut. A narrow metal bunk with sharp edges, fixed to the wall, and a metal toilet with no seat or curtain for privacy. This was to be my home for the foreseeable future, which wasn’t really foreseeable at all. I had no idea how long they would keep me in the “special housing unit” or SHU—a prison euphemism for solitary confinement.

It was a shoelace, of all things, that landed me here. I bent down to tie it, right as the Corrections Officer (CO) came by for the “stand-up count.” A few seconds earlier or later and I’d have been fine, standing to attention outside my bunk in the prison camp, as I did every morning at precisely ten, every afternoon at four, and every night at ten. The rotating blue light on the ceiling flashed to alert us that the guard was about to begin his walk through the dormitory, counting each inmate. The rules specify you must be standing straight, and not move or speak during the count. While technically I wasn’t upright, there was no way that my improper stance had impeded his ability to count me.

But it didn’t really matter. If it hadn’t been this it would have been something else. As I’ve learned the hard way, if someone in a position of unchecked power wants to lock you up, they can come up with an excuse to do so. It doesn’t take much at all. A moment of carelessness. A misjudgment. Bad timing.

I was jailed on June 17, 2014, for the crime of securities fraud, generally known as insider trading. In my case, specifically, I had been charged with being part of a conspiracy to pass privileged “nonpublic” information about Goldman Sachs and Procter & Gamble (P&G), two organizations on whose boards I sat, to Galleon hedge fund manager Raj Rajaratnam, who then bought or sold stock in those companies and made a profit, based on his “inside” knowledge.

There was no such conspiracy. Although I did not know it at the time, Rajaratnam had indeed cultivated an extensive network of insiders, each of whom he compensated well for providing him with tips. But I was never one of them. I did no trading in either of those stocks, I received no payments, and made no money. Raj was a business colleague (a poor choice, on my part, but not a criminal one) and my calls to him during 2008 and 2009 were all made in that context.

To prove insider trading, as it is legally defined, the government needed to prove three things: one, that I passed nonpublic information to Rajaratnam; two, that I did so as part of an explicit quid pro quo agreement in which I knew he would trade on it; and, three, that I received some benefit in return. They had evidence of none of these—no wiretap recordings of information being passed, no emails, no money trail, and no direct witnesses. Rajaratnam himself was never formally charged with illegally trading either Goldman or P&G, although in 2011 he was charged with and found guilty of insider trading in numerous other stocks, including Google, Polycom, Hilton, and Intel. The logic of charging me with these violations when they did not have evidence enough to charge the man who allegedly profited from them baffles me to this day. Moreover, no one could come up with a reasonable explanation for why I, a trusted advisor to countless corporations who had held sensitive insider information for decades, would suddenly decide to betray my fiduciary duties, and for no personal benefit. And yet I was found guilty, fined heavily, and sentenced by the judge to twenty-four-months’ imprisonment. The basis of my conviction was a handful of circumstantial interactions and hearsay statements that an overly zealous prosecutor spun into a conspiratorial narrative—one that was all too easy for a jury to believe in the wake of the financial crisis.

How did I end up labeled “the recognizable public face of the financial industry’s greed,” as one television anchor put it on the day of my arrest?1 I am an immigrant, born in Kolkata, one of the first wave of Indians to make their way to the US after the Civil Rights Act paved the way for landmark immigration law reform in the mid-1960s. When I arrived, in 1971, to attend Harvard Business School, I was one of only four Indians in my class. With few role models, I rose to the top of my field, becoming a consultant at the storied firm McKinsey & Company and working there for decades, eventually being elected the first non-American-born head of the firm. At the time of the charges, I’d already served my maximum term of nine years as McKinsey’s leader, and was still consulting part-time, while pursuing new opportunities in private equity and spending more than half of my time on global philanthropic causes. I also served on several prominent corporate boards, including Goldman Sachs and P&G.

In the eyes of the prosecutor, the Justice Department, and the general public, I was a big fish—a high-profile businessman with connections to the titans of industry and government. The Occupy Wall Street protesters who cheered my arrest didn’t care that I’d had nothing to do with the sub-prime mortgage meltdown that had triggered the financial crisis. Almost no one directly responsible for the crisis had been charged, and, meanwhile, ordinary Americans were losing their homes and their jobs. Now, finally, there was someone in the dock who was associated with major brands and household names. I was an easy target at a time when the public was desperate for someone—anyone—to be held accountable.

Bad Guy

“You don’t really like it here, do you?”

The Corrections Officer, a dour, heavyset man with a florid complexion, sat behind his desk, typing something on his computer. Following the shoelace incident, I had immediately made my way to speak to him, hoping to apologize and explain myself. Through the glass wall behind him, I could see into the TV room, which doubles as a visitors’ room on weekends. Just that afternoon, I had passed several hours there with Aditi, the third of my four daughters, catching up with her life. I’d listened empathetically to her stories, advised her on her career, and done my best to play a father’s role despite my circumstances. I treasured this kind of one-on-one time with my girls, even if it took place in a glass-walled room under fluorescent lights, amid a hubbub of conversations and vending machines. Now, with the visitors gone, the TV was turned back on, though the inmates seemed much more interested in peering through the window at my visit with the CO than in watching whatever inane show was playing on the screen.

The CO’s question struck me as odd. Like it here? I wasn’t aware we were supposed to like being in jail. And no, I didn’t exactly like it. But I suspected that the CO’s frustration with me actually stemmed from the fact that I was more content than most. Yes, I had many dark days, revisiting every detail of the events that landed me here, second-guessing my choices, agonizing over my mistakes. Yet in a curious way, I was quite happy, day-to-day, at the prison camp. I’d found a kind of equanimity in my daily routine. I walked for miles each morning on the track, enjoying the mild fall weather and the beauty of the surrounding foliage. I had friends. I played card games and Scrabble. I’d started a book club and a bridge club. There was a group of over-sixty guys with whom I’d eat breakfast and try to solve the world’s problems. Every weekend I had visitors—there were a hundred names on my list, which I knew irked my counselor. I followed the rules, as best I could, but I didn’t walk around like a repentant criminal. I felt more like a political prisoner.

So I knew full well that this reprimand wasn’t about my ill-timed shoe tying—it was an attempt to break my spirit. The guards took my intact dignity as a personal affront. They weren’t bad people, but they were keenly attuned to the dynamics of power and they expected inmates to be subservient. This particular guard was actually one of the more benign characters—he’d been there forever and rarely left his desk. There was only one thing he cared about: the count. “If you mess with the count, you disrespect him,” my fellow inmates had told me. “Don’t mess with the count and you’ll be okay.”

I apologized to the CO for my mistake and assured him it would not happen again, but he shook his head. “I warned you,” he said. “I warned you.” This was true—I had been a few seconds late for the count once before, lost in thought over a tricky move on a Scrabble board, and I had gotten off with a warning. Clearly, there would be no leniency this time around. He was writing up an incident report, he informed me, and I would be called in due course. Dismissed, I made my way to dinner. I knew I should eat, because if I was to be taken to the SHU there was no knowing when my next half-decent meal would be, but I felt sick to my stomach and could barely manage a few bites.

My mind was occupied with my upcoming visits—my wife, Anita, was due to come the next day with my other three daughters, Geetanjali (known as Sonu), Megha, and Deepali (known as Kushy). Two friends were flying in from Germany and India the following week. Would I be allowed to see them? And would my family worry about me even more when they heard? I knew I could cope; I was not sure I could convince them that I could cope. When the announcement blared out telling me to report to the CO’s office, I left my largely untouched dinner and set out to learn my fate.

The CO handed me the incident report he had written up, and asked me if it was accurate. It stated, correctly, that I had been tying my shoelace, but also that I had been listening to music, which I had not. Trying to adopt a deferential tone, but determined not to play his game, I told him that essentially it was accurate, but some details were wrong.

“So you’re disagreeing with me?”

“No,” I said carefully, “some of the details are incorrect, but I guess it does not matter. It is true that I was not standing for the count.” His expression made it clear that I had failed his test—I was not supposed to challenge his version of events.

“The disciplinary unit will decide on your punishment,” he told me, “but if I were you, I would get ready to go to the SHU.” Turning back to his computer, he left no doubt that our conversation was over.

Back at my bunk, I was inundated with advice from long-time inmates, many of them veterans of the SHU.

“Take a shower, while you can.”

“Put away your valuables.”

“Call your wife.”

“Give your wife’s number to a friend so he can call her.”

“Eat.”

I sat, frozen, the information coming at me too fast to process. The small cubicle, with its two bunks, two closets, two footlockers, and two chairs, suddenly felt like a home of sorts, compared to what awaited me at the SHU. I felt a strange pang at the thought of leaving it. Quickly, I gathered my few important possessions—my spare eyeglasses and my music player—and gave them to a friend for safekeeping. Before I had time to call Anita, I was summoned to the guards’ office.

Here, I was handcuffed. When I asked to use a restroom, the guards said no. After some time, one of the guards appeared with three plastic bags containing all my belongings, which he threw down carelessly on one side of the office. I wondered if I would see them again, and was grateful my friend had the things that mattered to me.

Eventually, four guards marched me to my new accommodations. I was put in a holding cell, strip-searched, and given an orange SHU uniform to wear. The entire process seemed unnecessarily rough and dehumanizing. I was not referred to by name; rather, they called me “the bad guy.” Still handcuffed, I was taken to my cell, where they locked me in and then instructed me to stick my hands through a small slot in the door so they could remove the cuffs. I asked if I could make a phone call to Anita and let her know not to come, but I was told “maybe next week.” Next week? My family were coming tomorrow, driving several hours to see me. The guard just shrugged. “So?” he asked as he walked away. I was left alone, sitting on the small steel stool, to adjust to my new surroundings and wrestle with the sense of injustice that once again threatened to overwhelm me.

Involuntary Simplicity

The cell was in fact not unfamiliar, since this was not the first time I’d been in the SHU. Four months earlier, on my arrival at FMC Devens, I’d spent my first few nights in an identical cell, before being transferred to the “camp” as the minimum security facility was known. I had hoped I would never be back here. Every inmate knows, however, that you can end up in the SHU at any time, for any reason. Friends would suddenly disappear for days, sometimes weeks, returning with a gaunt, haunted look and a heightened subservience to the guards. Now, it was my turn. Frustrated, I lay back on the lumpy, plastic-covered mattress, squashed to less than an inch thick by the weight of previous occupants, and closed my eyes.

As they often had during my imprisonment, my thoughts turned to my father. He too had spent many months confined to a cell. Although the context was completely different, I drew strength from his memory. More than seventy years earlier, Ashwini Gupta had been a freedom fighter on the front lines of India’s struggle for independence. He was jailed repeatedly by the British and suffered greatly at their hands. As a child, I remember staring at the knotted scar running the length of his back. When I was old enough to understand, he told me he had been beaten in jail until the flesh split open. The poor medical care he received left him with one leg shorter than the other, by almost two inches, and a permanent limp. Another scar commemorated the surgery that removed one of his lungs after a severe case of tuberculosis almost killed him. His British overlords had deliberately locked him up with a TB patient so that he too would become infected with the disease, fully intending that, like so many others, he would die in prison, suffering and alone.

He never said much about that episode—indeed, it was only much later in life that I learned the full story from other family members, including the fact that his infection had not been accidental. He only survived because, by a stroke of fate, one of the jailers in the prison where he lay racked by fever turned out to be an old friend and classmate, now working for the British. Seeing my father close to death, he arranged for an ambulance to take him to hospital, and also contacted his sister, my aunt, who came to care for him. If it had not been for that man, my father would have died in that cell.

Born in Kolkata in 1908, my father was a proud Bengali who exemplified the intellectual prowess and fiery, independent spirit of his people. His own health, safety, and happiness were never a primary concern in the fight for independence. Although he met my mother, Pran Kumari, in his early thirties, they were only wed in early 1947, when independence was visible on the horizon. My sister Rajashree (who I call Didi, meaning older sister) was born before the year was out, and I followed on December 2, 1948, with...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Part I: Crisis

- Part II: Karma Yoga

- Part III: Trial

- Part IV: Imprisonment and Freedom

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Acknowledgments

- Appendix: Timeline of Rajat Gupta’s Life

- Index