eBook - ePub

Roman Emperor Zeno

The Perils of Power Politics in Fifth-Century Constantinople

- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"A very useful read for anyone interested in the Later Roman Empire, the fall of the Western Empire, and the emergence of the Byzantine State." —The NYMAS Review

Peter Crawford examines the life and career of the fifth-century Roman emperor Zeno and the various problems he faced before and during his seventeen-year rule. Despite its length, his reign has hitherto been somewhat overlooked as being just a part of that gap between the Theodosian and Justinianic dynasties of the Eastern Roman Empire which is comparatively poorly furnished with historical sources.

Reputedly brought in as a counterbalance to the generals who had dominated Constantinopolitan politics at the end of the Theodosian dynasty, the Isaurian Zeno quickly had to prove himself adept at dealing with the harsh realities of imperial power. Zeno's life and reign is littered with conflict and politicking with various groups—the enmity of both sides of his family; dealing with the fallout of the collapse of the Empire of Attila in Europe, especially the increasingly independent tribal groups established on the frontiers of, and even within, imperial territory; the end of the Western Empire; and the continuing religious strife within the Roman world. As a result, his reign was an eventful and significant one that deserves this long-overdue spotlight.

"Crawford's work on the life and reign of Zeno is a good introduction for a general audience to the complexities of the late fifth-century Roman Empire, telling a series of long and complex stories compellingly in a traditional fashion." — Bryn Mawr Classical Review

Peter Crawford examines the life and career of the fifth-century Roman emperor Zeno and the various problems he faced before and during his seventeen-year rule. Despite its length, his reign has hitherto been somewhat overlooked as being just a part of that gap between the Theodosian and Justinianic dynasties of the Eastern Roman Empire which is comparatively poorly furnished with historical sources.

Reputedly brought in as a counterbalance to the generals who had dominated Constantinopolitan politics at the end of the Theodosian dynasty, the Isaurian Zeno quickly had to prove himself adept at dealing with the harsh realities of imperial power. Zeno's life and reign is littered with conflict and politicking with various groups—the enmity of both sides of his family; dealing with the fallout of the collapse of the Empire of Attila in Europe, especially the increasingly independent tribal groups established on the frontiers of, and even within, imperial territory; the end of the Western Empire; and the continuing religious strife within the Roman world. As a result, his reign was an eventful and significant one that deserves this long-overdue spotlight.

"Crawford's work on the life and reign of Zeno is a good introduction for a general audience to the complexities of the late fifth-century Roman Empire, telling a series of long and complex stories compellingly in a traditional fashion." — Bryn Mawr Classical Review

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Under Pressure: The Roman Empire of the Fifth Century

‘[Cato] makes speeches in the Senate as if he were living in Plato’s Republic, instead of this sewer of Romulus.’

Cicero, Letters to Atticus II.1.8

Appearances Can be Deceiving: Decline, Division and Disunity

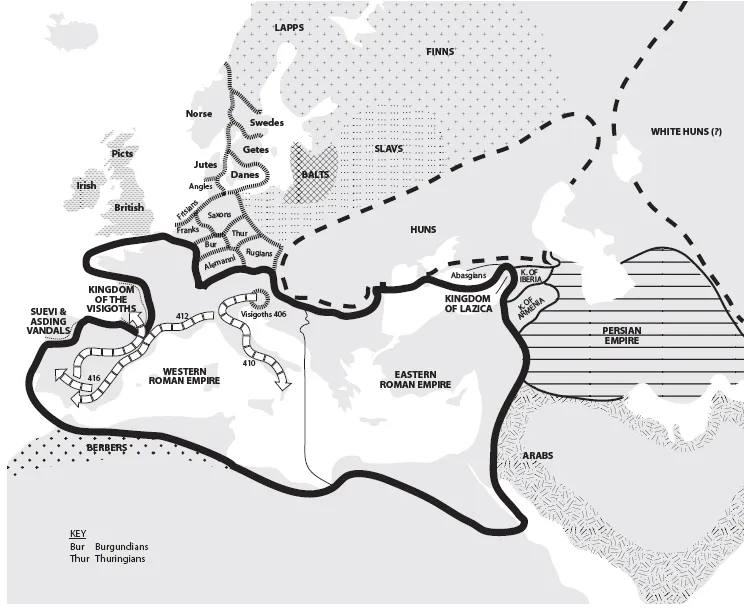

Look at a map of the Roman Empire in 420 and you might be forgiven for thinking that talk of a decline was a little overblown. In terms of outline, the empire does not look all that different from its fourth-century predecessor. Even a generation later at the outset of the 450s, while some regions had fallen out of imperial control – Britain, western Gaul, western Spain and the province of Africa – the overall integrity of the empire appears to be sound. But appearances can be deceiving. On such maps, the eye is immediately drawn to the presence of barbarian tribes establishing their own proto-kingdoms on formerly imperial territory: Franks, Burgundians and Goths in Gaul, Suebi in Spain, Vandals in Africa and the opening gambits of German tribes in Britain. Surely their establishment had been at the point of a sword, bringing all kinds of death, destruction and decline to the Roman Empire?

The great movement of Germanic peoples – the Völkerwanderung – had seen numerous tribes cross into Roman territory either as displaced refugees, desperate migrants or opportunistic invaders; however, it is too simplistic to say that this influx caused the imperial infrastructure to crumble. The Roman state had proven capable of resisting such intrusions along the Rhine-Danube frontier in the past, and at least two barbarian tribes operating on Roman territory by the turn of the fifth century – the Goths and the Franks – were there by the invitation of the Roman government. Something had to have changed within the Roman Empire for its policies to fail so spectacularly in the late fourth century. The lack of clarity about what that something might have been was summed up by Alexander Demandt in his 1984 work, Der Fall Roms, where he tabulated a list of 210 reasons for the decline of the Roman Empire.1

While some Roman decline seems assured, looking at the same map would seem to present a more definitive confirmation of the division of the Roman Empire into eastern and western halves; however, again, the reality was not so straightforward. The division of 395 was hardly the first time there had been more than one emperor ruling different parts of the empire at the same time. The fourth century had begun under the ‘rule of four’ that had been the Tetrarchy; the death of Constantine I in 337 had seen the empire divided between his three surviving sons; while there had been at least two reigning emperors since Valentinian I elevated his brother Valens in March 364. None of these was ever taken to be a proposed permanent division of the empire into separate states, so there is no reason to suggest that the succession of Arcadius and Honorius as eastern and western Augustus respectively on the death of their father, Theodosius I, in 395 was meant to represent one either.

Roman Empire in 420

Dynastically, there was no divide at all. Aside from a brief western interlude with the usurpation of Ioannes in 423–425, the Theodosian dynasty ruled both halves of the empire until the mid-450s. Eastern emperors frequently acted on what they saw as their duty to maintain the dynastic stability and territorial integrity of at least some parts of the west. Eastern forces campaigned in the west and several western Augusti owed their selection to an emperor of Constantinople. In terms of laws, most generated by Constantinople or Ravenna would feature the name of both emperors, so long as he was recognized by the respective imperial courts. Right up until the expiration of the western empire, and indeed beyond that, this division into Eastern and Western Roman Empires was technically non-existent.

In reality, there was a growing division between East and West as the fifth century progressed. Many aspects of what would make for a permanent split were in place before the death of Theodosius I. The growth of Constantinople had made it so that the empire had two imperial capitals, each with its own court, Senate, armies, clearly defined spheres of influence and all attendant bureaucracies. These alone had not been a problem during the periods of east/west division of the fourth century; the major differences post-395 came in the type of governments which controlled each half. In the last months of his reign, Theodosius had left his eldest son Arcadius to rule at Constantinople while he travelled west to deal with the usurpation of Eugenius; however, Arcadius was still only 17 and needed help, with the choice falling on the praetorian prefect Rufinus. As Arcadius proved uninterested in ruling, this gave the Constantinopolitan government a civilian feel. This contrasted with the more military government set up under Stilicho in the West after Theodosius’ victory over Eugenius at Frigidus. The subsequent demise of Theodosius left these civilian and military-led governments in place, with Stilicho and Rufinus appointed as guardians of their respective young emperors. This contrast was exacerbated by Stilicho’s claim that he had been named guardian of both Theodosian sons. This led to political confrontation between East and West, which distracted Stilicho and undermined the imperial response to the likes of Alaric.

The longevity of several Theodosian emperors also proved a significant issue. It was not only Arcadius who proved unsuited to imperial rule – Honorius, Theodosius II and Valentinian III were all long-reigned but largely ineffective. These emperors also acceded to power at young ages: Honorius was 10, Theodosius II was 7 and Valentinian III was just 6. This allowed other individuals to lead the imperial government. Theodosian women like Galla Placidia, Pulcheria, Eudocia and Eudoxia wielded increasing influence over the future of the dynasty, providing a legacy for Verina and Ariadne of the House of Leo. The failure of Theodosian emperors to take the field at the head of the army after 395 saw increasing power fall to generals such as Stilicho, Flavius Constantius and Aetius. The effect was slightly delayed in the East by a limited demilitarization, but as will be seen, Aspar was a well-established power behind the throne by the mid-450s. Along with the Suevo-Goth Ricimer in the West, the Alan Aspar also demonstrates the rise of Romanized barbarians within the military hierarchies.

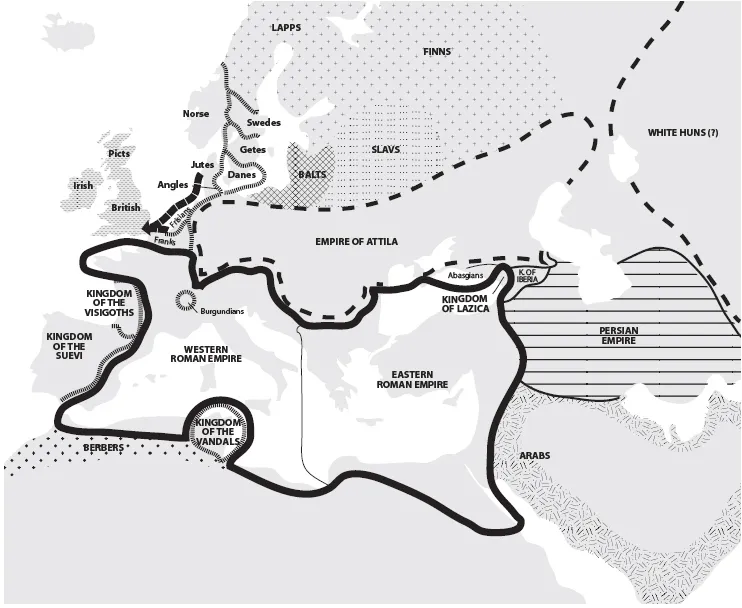

Roman Empire in 450

The rise of non-Theodosian or non-imperial powers behind the throne led to divergent and even opposing policies. This was exacerbated by Ravenna and Constantinople facing different problems caused by their differing geography. Barbarians crossing the Rhine or Danube into western territory were immediately into the heart of the western empire, and while Illyricum and Thrace were similarly vulnerable, the eastern empire ruled a wide arc of rich territory from the walls of Constantinople through the Middle East to Egypt, which was largely free from invasion. In the West, not even those provinces separated from the European continent by the sea – Africa and Britain – proved safe from barbarian conquest. Therefore, while it was not a planned and definitive political split in 395, dynastic politics, personal ambitions, geography and military decline made it one with the fullness of time.

It was not just politically that the Roman Empire was no longer quite so united. The fourth century had seen the triumph of Christianity in the Roman Empire, going from a persecuted minority to the faith of the imperial family and ultimately the empire itself within a century. One of the biggest reasons why Christianity had been so successful was its strong organization, taking many of its cues from the Roman Empire itself. However, without a persecuting pagan empire to provide a lightning rod for all the energies of the Church, Christianity become more introspective. Local autonomy, regional cultures and philosophical debate sparked disagreements over various aspects of doctrine.

This meant that while the Roman state was united under Christianity, Roman Christianity was far from united. The focus of this doctrinal dispute was the divinity of Jesus of Nazareth – as the Son of God, had He been created by God and was therefore in some way inferior? Succeeding Ecumenical Councils – Nicaea in 325, Constantinople in 381, Ephesus in 431 and Chalcedon in 451 – had attempted to settle this issue, but the introduction of various terms only served to further muddy the waters and provide more areas of disagreement. The decline of the western empire and the growth of Constantinople as an imperial capital also prompted disunity within the Church hierarchy. The pope came under pressure from the patriarch of Constantinople in terms of influence, while other eastern patriarchates – Antioch, Alexandria and Jerusalem – rankled under the doctrinal and hierarchal primacy of Constantinople. This was to cause significant trouble not just for the Roman church but also imperial authorities, with Zeno spending a lot of his reign attempting to find solutions to these problems.

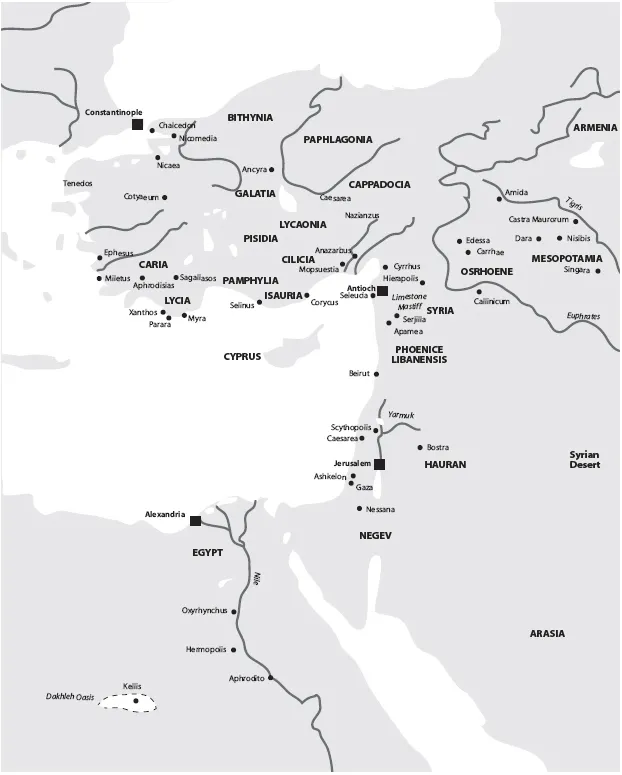

Eastern Provinces

Christianity may have won out in the fourth century, but that did not mean that other faiths disappeared overnight. Various forms of paganism remained prevalent throughout the fifth century, although those issues may be as much Christians portraying pagans as more of a political and religious nuisance than they really were. Jews were portrayed in a similar light, with past revolts used as justification for viewing them as ‘fifth columnists’; however, the only involvement Zeno would have with Jews was when Christian groups partook in their own anti-Semitism. It was the other ethno-religious group in Palestine who were to cause Zeno political, religious and military trouble: the Samaritans.

The Spectre of Attila

The Samaritans were not the only internal military problem faced by Constantinople in its eastern provinces. As will be seen, Zeno’s own Isaurian countrymen continued to be a source of considerable political and military disturbance. The eastern Roman provinces also bordered a series of non-Roman kingdoms. Where there had once been the Achaemenid Persian Empire crushed by Alexander the Great, and then the Parthian kingdom, which had resisted the triumvirs Crassus and Antony, there was now the Sassanid Persian Empire. Since the 230s, Romano-Persian relations had seen repeated conflict; however, while the territorial and religious squabbles of the other kingdoms of the Middle East – Armenia, Iberia, Lazica and Caucasian Albania – might occasionally drag in the two great powers, Rome and Persia had their own internal and external distractions. This meant that the ‘apparently neverending cycle of armed confrontations’2 took a prolonged rest during the fifth century.

The quiet which overtook the fifth century eastern frontier could not have come at a better time for Constantinople as its other major frontier, the Danube, was coming under increasing pressure. Legionary bases all along the river put vast amounts of wealth in the pockets of soldiers, leading to a significant number of towns of increasing size such as Naissus and Singidunum growing in the Danubian hinterland. This combination of military and agricultural infrastructure on top of the rugged terrain saw Danubian manpower become much sought after, leading to men of such origins becoming candidates for imperial power throughout the third and fourth centuries. This imperial backing saw those towns not only grow further but become adorned with temples, churches, palaces, theatres, aqueducts, roads, statues and villas.

However, these decades of growth came to a shuddering halt in the late fourth century. The crushing of the Limigantes by Constantius II in the late 350s upset the tribal balance beyond the Danube, with the Goths establishing themselves as a dominant force. They proved a very tough nut for Valens to crack in 367–369,3 although he was successful enough to leave the Goths desperate to seek his permission to settle in the empire. The subsequent disaster at Adrianople in 378 was only the beginn...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction A Roman Game of Thrones

- List of Emperors and Kings

- List of Maps

- List of Illustrations

- Chapter 1 Under Pressure: The Roman Empire of the Fifth Century

- Chapter 2 The Romanized ‘Barbarians’: Isauria and the Origins of Zeno

- Chapter 3 Enemies in the State: The Gothic ‘Nations’ of the Theoderici

- Chapter 4 Puppet on a String? The Reign of Leo I

- Chapter 5 The Pressure Grows: Huns, Vandals and Assassins

- Chapter 6 The Puppet Becomes the Butcher: The End of Aspar

- Chapter 7 A Father Succeeding his Son: The Making of Flavius Zeno Augustus

- Chapter 8 A Brief Imperial Interlude: The Usurpation of Basiliscus

- Chapter 9 Beholden to All: The Price of Zeno’s Restoration

- Chapter 10 All Quiet on the Eastern Front?

- Chapter 11 Zeno, the Christological Crisis and Imperial Religious Policy

- Chapter 12 A Long Time Coming: The Revolt of Illus

- Chapter 13 Zeno, Theoderic and the End of the Western Roman Empire

- Chapter 14 Demonic Possession, Vivisepulture and a Woman Scorned: The Death of Zeno and the Succession

- Conclusions The Paradoxes of Zeno Augustus

- Appendix The ‘Fatal Throw’ – Zeno’s Game of TαβLλη

- Endnotes

- Bibliography

- Plate section

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Roman Emperor Zeno by Peter Crawford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.