![]()

1

Robert E. Lee

An abrupt downpour washed out the event, but it could not forestall Robert E. Lee’s deification. On February 22, 1884, a crowd of fifteen thousand converged on Tivoli Circle in New Orleans to witness the unveiling of the Lee Monument. After Lee’s death in 1870, the Lee Monumental Association raised $10,000 for a young New York sculptor, Alexander Doyle, to create a sixteen-and-a-half-foot statue in bronze and raised an additional $26,000 for the local architect John Roy to erect a sixty-foot marble column set on top of a pyramidal base of granite. It was a prodigious accomplishment, considering that the city had suffered financial ruin in the Panic of 1873. The 104-foot structure, along with the Shot Tower (1883) and the New Orleans National Bank (1882), defined the cityscape when engineers were just beginning to master the challenge of building vertically on a high water table.

The Monumental Association included notables such as General P. G. T. Beauregard, CSA; Louisiana Supreme Court justice and Confederate veteran Charles Erasmus Fenner; and the cotton merchant Michael Musson, uncle of Edgar Degas. It was Carnival season, and the Committee of Arrangements organized the event like the tableaux of a Mardi Gras ball. Historians have marked the period between 1870 and 1914 as an “era of invented tradition” in which events were staged as if they were steeped in ancient ritual.1 The pageantry of the Lee memorial was the first of its kind, coming six years before Richmond followed suit. The program was to honor Robert E. Lee with a poem written specifically for the unveiling, as well as a lengthy oration by Judge Fenner. Three thousand chairs were set on the west side of the monument for ladies who arrived an hour before the festivities were to commence. On the platform were six hundred seats for big donors, nabobs, the Louisiana Supreme Court, members of Congress, the Monumental Association, and the Ladies Confederate Monumental Association; consuls-general of France, Great Britain, Germany, Mexico, the Netherlands, and the Dual Monarchy of the Austro-Hungarian Empire; and Confederate royalty, including Jefferson Davis and his two daughters; Lee’s two daughters, Mary and Mildred; and Mrs. T. S. Kennedy, the daughter of Confederate secretary of war Stephen Mallory. All the Confederate veterans’ groups, the associations of the Armies of Tennessee and Northern Virginia, and the Confederate States Calvary were represented; and significantly, in a spirit of reconciliation, two posts of the GAR (Union veterans of the Grand Army of the Republic), along with a National Guard unit from Detroit, were there by invitation. At the foot of the monument, the flags of the foreign consulates fluttered in the wind as a band struck up Richard Wagner’s “Grand March Rienzi.” But just as the proceedings were about to begin at 2:00, the sky grew dark, and a torrential rain drove the crowd indoors. Yet the veterans of the blue and gray were undeterred, and when two “maimed veterans” pulled a cord revealing the sculpture, a loud cheer went up.

The ceremony resumed for the dignitaries in the armory of the Washington Artillery, the most prestigious and oldest of New Orleans military units. Charles Fenner, president of the association, presented the monument to Mayor William Behan, who, as a young officer in the Washington Artillery, had surrendered with Lee at Appomattox. Fenner, who was never lost for words, used the occasion to link Louisiana to the Lee myth: “Louisiana is entitled to a full share in the glory of Lee. Her sons illustrated by her valor every field on which his fame was won.”2 President of the Association of the Army of Northern Virginia and future governor Francis T. Nicholls assured Lee’s daughters, “The blood of Louisiana was poured out on a hundred hills and plains of Virginia: but they had done it willingly for Robert E. Lee and for duty.”3

Alexander Doyle was twenty-seven years old the year of the unveiling, and though he lacked the talent of an Augustus Saint-Gaudens, he was extraordinarily prolific. One newspaper claimed that, at thirty-three, “he had done more public monuments than any other sculptor, and was producer of more than a fifth of those standing in the country.”4 Scion of a wealthy family in Steubenville, Ohio, Doyle was taken by his parents to Italy, where he was raised to be an aesthete, studying music, painting, and sculpture. After two years in the states to finish high school, he resumed his studies in sculpture in Italy, returning in 1878 to start a business in New York City. And it was a business; Doyle’s family owned a limestone quarry in Indiana, and he parlayed his family’s connections in limestone, granite, and marble into commissions for sculptures.5 He would go on to produce five major works in New Orleans.

Doyle’s Lee, on close inspection, leaves the viewer cold; as a work of art, it does not move or evoke. Stolid and phlegmatic, it is not the kindly “Marse Robert” of hagiographers. It clearly lacks the technical virtuosity of Doyle’s other works such as the bronze statue of Albert Sidney Johnston located at the Army of Tennessee tumulus in Metairie Cemetery. It also lacks the profundity of his elegant marble sculpture of Margaret Haughery or the majesty of his equestrian statue of Beauregard, which graced the entrance of City Park until 2017.6 Yet high up on his perch, General Lee had an aesthetic. The effect was more totemic and theatrical than artistic. Doyle’s Lee was coolly poised to face another Yankee invasion with his arms folded, facing north; the statue projected the defiance that was essential to the Lost Cause myth. And while New Orleans begged credulity as a Confederate city, the idea of the monument dedication by urban elites was to leave no doubt that New Orleans had come to rival Richmond as a bastion of Confederate civic ideology.

According to the Jung scholar Joseph L. Henderson, “As a general rule it can be said that the need for hero symbols arises when the ego needs strengthening.”7 New Orleans had undergone a double humiliation, military defeat and Federal occupation from 1862 to 1877. Along with the rest of the South, Confederate veterans and partisans turned to the Lost Cause as a palliative. The narrative turned into a catechism—Southern valor and heroism were to be celebrated; secession was about a constitutional disagreement, with the South defending its rights as a sovereign state, and slavery a nonissue. In his own life, Robert E. Lee preferred to “obliterate the marks of civil strife” regarding memorials but became the patron saint of the Lost Cause. As a symbol, he assuaged Southern guilt and gave hope to the vanquished. He held a mirror up to the South, and later to the whole country, of a civilization lost only to be replaced by Gilded Age plutocrats and the avarice that defined the era.

It was not a coincidence that the dedication took place on George Washington’s birthday. By the 1880s, southern apologists aggressively attempted to link the Confederacy to a national mythology through the Lee persona. Lee’s connections to Washington were legitimate, since his father was the Revolutionary War hero “Light-Horse Harry” Lee, who was a favorite of the commander in chief, and Lee the son married Mary Custis, the step-great-granddaughter of Washington. That Lee took up arms against the United States was a mere technicality. In a great example of Gilded Age legerdemain, the Confederate cause became patriotic, and Lee, as Kirk Savage has argued, “was the obvious man to personify a newly revised, newly remembered Confederacy—a Confederacy that pretended to have fought a heroic struggle not for slavery but for liberty, defined as the right of states to self-determination.”8 In his oration at the dedication, Judge Fenner defended secession as positively American, a tradition that went back to the colonial separation from Great Britain. The problem was that by 1860, the North had embraced Daniel Webster’s theory of a national government, as opposed to the Southerners who had remained loyal to the idea of a federal government and its concomitant state compact theory of government. Hence the war was simply a misunderstanding, and Lee himself was “one of the greatest of Americans.”9

The dedication speech played in the New Orleans newspapers the next day. No Lost Cause tropes were spared for Lee’s ascension to the empyrean. Fenner started with Lee’s lineage, which was apropos at a time when Americans were obsessed with race and ethnicity:

The blood which coursed in his veins descended in purest strain through an illustrious ancestry running back to William the Conqueror every record of which indicates a race of hereditary gentlemen. That the blood of Launcelot Lee who landed with the Conqueror and of Lionel who fought with the Coeur De Lion, had not degenerated as it percolated through the centuries is evidenced by the history of the American Lee whose founder was Richard Lee, a courier of Charles the First.10

Part of a Southern myth constructed in the 1850s was the notion that Southerners descended from the Normans; hence the feudal martial tradition that differentiated them from the Anglo-Saxons of the North, who were more interested in pecuniary gain.11 This also played into the Cavalier myth that the South, especially Virginia, was a refuge of royalists in the English Civil War, while the Roundheads flocked to New England, creating a dour society that hanged witches and heretics.12 Lee was the paladin of Sir Walter Scott novels, a fixation in the South, where jousting tournaments became a craze in the 1890s. While the idea of a Norman inheritance faded after the war, the conceit that the South was a superior civilization refused to die. Even H. L. Mencken, who regarded the South of his own era as a cultural wasteland, wrote in 1920 that, before the Civil War, the South had been “a civilization of manifold excellences—perhaps the best that the Western Hemisphere had ever seen—undoubtedly the best that These States have ever seen.”

America was still predominantly an evangelical country in the Gilded Age. Lee, by resisting the “glittering temptation” of the field command of the Federal army in 1861, had replicated Christ’s temptation in the desert. Like Jesus, Fenner professed, Lee was actually never really tempted: “My study of his character forbids me to believe that such considerations ever assumed the dignity of a temptation to him.”13 Purity of spirit defined Lee, and he constituted what American Protestants desperately wanted to see in themselves.

Nevertheless, the social Darwinists also revered Lee. When it came to ranking the human species, he was on the top pseudoscience rung, the apotheosis of the Anglo-Saxon Christian gentleman. As Thomas Connelly has argued, Lee was becoming a national hero at a time when the country was “threatened by unsettling forces,” namely, eastern and southern European immigration, along with a rapacious industrialization.14 Charles Francis Adams, a Union army veteran, brother of the historian Henry Adams, and an ardent social Darwinist, gave a paper to the American Antiquarian Society in 1901 honoring Lee titled “The Confederacy and the Transvaal: A People’s Obligation to Robert E. Lee.” Looking to the Boer War as a cautionary tale after the fact, Adams argued that Lee had saved the country by sending his men home rather than into the mountains to carry on a protracted guerrilla war.15 By doing so, Lee promoted reconciliation.

Reconciliation and the Lost Cause became two sides of the same coin in the 1880s. The celebration of Southern manhood and valor was a way to rebuild the country. The caveat was that the South could reconcile on its own terms. Two independent narratives developed in the North and South, and any rights Southern Blacks achieved during Reconstruction withered away. In New Orleans, where Confederate and Union army veterans lived in the same locale, and where there had been a critical mass of Unionists during the war, reconciliation was a necessity if the city was going to regain its prewar status as a preeminent economic power. And according to Louis Harlan, Republican merchants of the city tended toward a “Whiggish Republicanism” more interested in “sugar protection and internal subsidies for river and harbor improvements and railroads” than a radical vision.16 Reconciliation was good for business, and gradually the Confederate faction offered up its own terms that became the standard civic ideology.

Reconciliation in New Orleans officially started with US soldiers and sailors marching on Mardi Gras in the Rex parade of 1876. The New Orleans Times wrote, “It clearly indicates what has been reiterated that nowhere could be found people more truly devoted to the nation, nor more anxious to obliterate all acrimony than we of the South.” As David Potter argued, regional identity and national identity are, in fact, complementary rather than antithetical, and as long as the South could reconcile on its own terms, “patriotism to the nation,” as Rollin Osterweis averred, became largely peculiar to the South.17

Six months before the Lee dedication, the Joseph A. Mower post of the GAR received a letter from a joint committee of the Associations of the Armies of Northern Virginia and Tennessee: “The reciprocal feelings of respect and amity that have grown up between your organization and those we represent lead the committee to hope that you will find it possible to give them active cooperation in the mimicry of war they desire to represent.”18 The “mimicry of war” was to be a Civil War–style reenactment to raise money for a Confederate Soldiers’ Home in the Crescent City. The veterans’ associations promoted the affair as a “Grant Lottery Scheme.” For a dollar ticket, one could view the entertainment to be held at the Fairgrounds and participate in the drawing for one hundred prizes ranging from a “handsome cottage” on Constance Street worth $1,500 to a cup and saucer.19

Significantly, the event was billed not as a North-South contest but simply as a two-day battle between the home team and the invaders, with Union and Confederate veterans on both sides. Ten thousand spectators attended, and by all accounts, the event was a grand success: charges and retreats, flanking maneuvers, firefights, and artillery barrages provided the onlookers with an authentic Civil War experience. The newspapers covered the reenactment like a sporting event and even participated in the sham with laconic reportage such as “Major Willett of the Veterans Battalion had his lower jaw torn off by a shell, but this is not confirmed.”20 After the valiant adversaries fought to a draw, participants and spectators repaired to the Great Hall of the Fairgrounds and danced into the morning hours.

By the day of the dedication of the Lee Monument, reconciliation had become the norm. After laudatory remarks about Lee’s heritage, the perfection of both Lee’s appearance and his soul, the legality of secession, Lee’s genius as a field commander, and the Lost Cause, Fenner was careful to end his address by praising the Union veterans: “Let nothing I have said be constituted as disparaging the valor of the Union troops, the skill of their leaders or the splendor of their achievements.”21

But for some citizens, reconciliation came at a price. Less than a mile away from the dedication, a special committee of the US Senate under Republican George Hoar of Massachusetts conducted hearings regarding elections in Copiah County, Mississippi. The situation was so explosive that the committee conducted the investigation in New Orleans rather than Hazlehurst, the county seat. The violence stemmed from a movement by a former sheriff, John Prentiss “Print” Matthews, to organize an Independent Party that included both poor Black and white farmers. Mathews came from a prominent slaveholding family but had sided with the Union throughout the war. During Reconstruction, he became a powerful Republican, serving three terms as sheriff. Copiah County had a slim Black majority, with approximately 14,000 Blacks to 13,000 whites. When Matthews organized his Independent Party in 1883 and lured some white Democrats into the ranks, the local Democratic Party formed a paramilitary organization of “night riders” with 150 armed men who terrorized the Black population by murder and torture. The leader of the group, Erastus Wheeler, was actually a friend of Matthews, which makes it all the more bizarre that it was Wheeler who fired a double-barreled shotgun into Matthews’s chest on election day, mortally wounding him.22 Matthews had two sons away at college and two daughters and a wife at home. The Democrats carried the county by two thousand votes. Wheeler was acquitted by an all-white jury under the claim of self-defense.

Senator Hoar’s majority report was a scathing indictment of the political situation in Copiah County. The minority report of the Democratic senators was a disgrace: the paramilitary group was just some lawless individuals who had no connection to the Democratic Party, Black witnesses were unreliable, and Matthews probably had it coming to him for stirring up trouble. The two Democratic senators on the committee, Eli Saulsbury of Delaware and Benjamin F. Jonas of Louisiana, were seated on the platform at the monument dedication that would transform military defeat into moral victory and establish Lee for all eternity as an American hero.

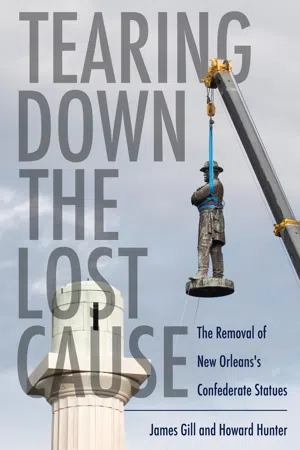

The crowd was too enraptured to contemplate the lesson of Ozymandias and could never have imagined the scene that would unfold on that very spot 134 years later. Where former rebels had attended what amounted to Lee’s canonization, a later generation would gather in distinctly unreverential mood when the day for the statue’s removal arrived. It was the ultimate indignity for an icon that had dominated the skyline for generations, but a feeling almost of anticlimax reigned around Lee Circle. A sense that the occasion was historic and portentous was much more in evidence in an antebellum Greek revival building a few blocks away, where Mayor Mitch Landrieu rose to his feet just as masked workers clambered onto a crane and prepared to winch the statue from its perch on May 19, 2017. Landrieu was there to explain his rationale for removing the Confederate memorials from the streets of...