- 318 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Contributions by José Alaniz, Ian Blechschmidt, Paul Fisher Davies, Zanne Domoney-Lyttle, David Huxley, Lynn Marie Kutch, Julian Lawrence, Liliana Milkova, Stiliana Milkova, Kim A. Munson, Jason S. Polley, Paul Sheehan, Clarence Burton Sheffield Jr., and Daniel Worden

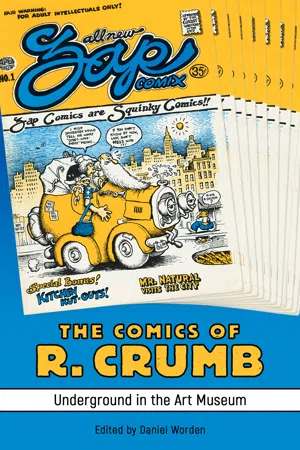

From his work on underground comix like Zap and Weirdo, to his cultural prominence, R. Crumb is one of the most renowned comics artists in the medium's history. His work, beginning in the 1960s, ranges provocatively and controversially over major moments, tensions, and ideas in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, from the counterculture and the emergence of the modern environmentalist movement, to racial politics and sexual liberation.

While Crumb's early work refined the parodic, over-the-top, and sexually explicit styles we associate with underground comix, he also pioneered the comics memoir, through his own autobiographical and confessional comics, as well as in his collaborations. More recently, Crumb has turned to long-form, book-length works, such as his acclaimed Book of Genesis and Kafka. Over the long arc of his career, Crumb has shaped the conventions of underground and alternative comics, autobiographical comics, and the "graphic novel." And, through his involvement in music, animation, and documentary film projects, Crumb is a widely recognized persona, an artist who has defined the vocation of the cartoonist in a widely influential way.

The Comics of R. Crumb: Underground in the Art Museum is a groundbreaking collection on the work of a pioneer of underground comix and a fixture of comics culture. Ranging from art history and literary studies, to environmental studies and religious history, the essays included in this volume cast Crumb's work as formally sophisticated and complex in its representations of gender, sexuality, race, politics, and history, while also charting Crumb's role in underground comix and the ways in which his work has circulated in the art museum.

From his work on underground comix like Zap and Weirdo, to his cultural prominence, R. Crumb is one of the most renowned comics artists in the medium's history. His work, beginning in the 1960s, ranges provocatively and controversially over major moments, tensions, and ideas in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, from the counterculture and the emergence of the modern environmentalist movement, to racial politics and sexual liberation.

While Crumb's early work refined the parodic, over-the-top, and sexually explicit styles we associate with underground comix, he also pioneered the comics memoir, through his own autobiographical and confessional comics, as well as in his collaborations. More recently, Crumb has turned to long-form, book-length works, such as his acclaimed Book of Genesis and Kafka. Over the long arc of his career, Crumb has shaped the conventions of underground and alternative comics, autobiographical comics, and the "graphic novel." And, through his involvement in music, animation, and documentary film projects, Crumb is a widely recognized persona, an artist who has defined the vocation of the cartoonist in a widely influential way.

The Comics of R. Crumb: Underground in the Art Museum is a groundbreaking collection on the work of a pioneer of underground comix and a fixture of comics culture. Ranging from art history and literary studies, to environmental studies and religious history, the essays included in this volume cast Crumb's work as formally sophisticated and complex in its representations of gender, sexuality, race, politics, and history, while also charting Crumb's role in underground comix and the ways in which his work has circulated in the art museum.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Comics of R. Crumb by Daniel Worden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Comics & Graphic Novels Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University Press of MississippiYear

2021Print ISBN

9781496833761, 9781496833754eBook ISBN

9781496833778Part IV

THE FINE ART COMICS

Chapter 10

ROBERT CRUMB AND THE ART OF COMICS

DAVID HUXLEY

A distinctive feature of Robert Crumb’s career has been the early, and continuing, interest in his work from art historians. He was featured in the journal Art and Artists as early as 1969. In 1972, art critic Robert Hughes described him as “a kind of American Hogarth,” and in Terry Zwigoff’s 1995 documentary Crumb, Hughes describes him as “the Bruegel of the last half of the twentieth century.” The list of respected art historians queuing up to praise Crumb is quite impressive, and this has generated a great deal of critical material. As early as 1981, Don Fiene’s R. Crumb Checklist compiled 170 pages listing works by, and writings on, Crumb. Subsequent years have done nothing to dampen critical interest in his work, and for a man who has a reputation as a recluse, he has given a large number of interviews throughout his career.

ART AND GRAPHICS: A VIEW FROM THE 1960S

The idea of discussing Crumb in relation to art is hampered by the massive problem of defining “art” itself. There are also many various ways of defining practitioners—they might be described as artists, fine artists, illustrators, graphic artists, or indeed comic artists. Each term carries a different connotation in relation to the perceived status of the person described. In practical terms, it is impossible to resolve these problems in the space available here. In the field of the visual arts, everything from a “readymade” to a Pollock drip painting to a Leonardo anatomical drawing could be included. Thus, indeed, it might not be possible to provide an adequate definition even with much more space available—the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy takes nineteen pages and over ten thousand words in an attempt at a definition and includes a disclaimer that the exercise may in the end be fruitless: “[T]he phenomena of art are, by their nature, too diverse to admit of the unification that a satisfactory definition strives for, or that a definition of art, were there to be such a thing, would exert a stifling influence on artistic creativity” (Adajian 2018).

When asked about the status of his “readymades” as art, the iconoclast artist Marcel Duchamp explained:

Can we try to define art? We have tried. Everybody has tried. In every century there is a new definition of art, meaning that there is no one essential that is good for all centuries. So if we accept the idea of trying not to define art, which is a very legitimate conception, then the readymade comes in as a sort of irony, because it says, “Here is a thing that I call art, but I didn’t even make it myself.” As we know, “art,” etymologically speaking, means “to hand make.” (Hamilton 2018)

The rest of this chapter will be, in effect, a discussion that leads to an implied definition of art, one that can account for the comics of R. Crumb and the potential view of him as a “fine artist.” Toward this end, I will analyze the nature and quality of Crumb’s drawings and the influences on his style. One facet of Crumb’s comics art is that, despite the fact that it is largely mechanically reproduced through printing, it nonetheless bears intentional marks of the “handmade,” a notion that connects Crumb to people like Duchamp and also figures prominently in Crumb’s own understanding of his work as art.

Yet Crumb’s attitude to fine art is made crystal clear on the back cover of a 1969 issue of Plunge into the Depths of Despair comics. Under the headline “Drawing Cartoons Is Fun!,” a simple stick-figure version of Crumb indicates a bearded, haloed figure on a pedestal in a traditional artist’s smock. The figure is labeled “Faker” in large letters, and the text explains: “ART is just a racket. A HOAX perpetrated on the public by so-called Artists’ who set themselves up on a pedestal and promoted by panty waste [sic] ivory-tower intellectuals and sob-sister ‘critics’ who think the world owes them a living!” Over a photograph of a woman fondling a shoe, the text continues: “It doesn’t take a ‘genius’ to transform the photo on the left into the cartoon below! A sense of humor is all that’s needed!” Unfortunately, Crumb’s drawing is a skillful cartoon that owes little to the photographic source, which rather undermines the claim next to the drawing that “[t]here is no such thing as ‘inborn talent.’” Nevertheless, Crumb’s distaste for the art world is palpable, if somewhat ironic in relation to his current standing in the art world.

The difficulty of drawing like Crumb is demonstrated in a parody of his work that appeared in the January 1972 issue of National Lampoon, a publication that is characterized by its extreme irreverence. This issue, titled “Is Nothing Sacred?,” features an image on the cover of Che Guevara being hit in the face by a large egg. The Crumb parody, “Fritz the Star,” was written by Michael O’Donoghue, and the first two pages are essentially an attack on Crumb’s Fritz the Cat through film director Ralph Bakshi’s animation of the character, which Crumb hated unreservedly. The strip in National Lampoon was drawn by the perfectly capable and often dynamic cartoonist Randall Enos, and although he is able to catch something of the early look of Fritz in some panels, his crosshatching carries none of the conviction and control found in Crumb’s work. The third page shows “Crumbland,” a kind of underground Disneyland, but there is none of the strong design and clear composition so often found in Crumb. On the final page, there is a version of Crumb (which does not catch his style at all) who is described as “America’s best-paid underground cartoonist,” and who exclaims: “Honest, kids, I haven’t sold out! My staff and I are gonna keep dishin’ up those swell commix about ’51 Hudsons and big lipped spades that say ‘Yowsuh!’ and ‘Sho ’nuff!’ and ‘Lawzy me!’ and cakewalking ketchup bottles and gandy goose and chubby squab-job teenyboppers with shiny boots and wow hooters …” (O’Donoghue 1972, 61). The parody in fact largely misses the point, as Crumb, often struggling for money, prided himself in not “selling out.”

In an issue of The People’s Comics from 1972, in “The Confessions of R. Crumb,” the author sits at his desk with a note saying, “Notice: R. Crumb does not sell out.” Next to this is a trash basket with crumpled paper showing offers from “big time publishers” and agencies, which Crumb occasionally did receive. National Lampoon is also somewhat hypocritical in criticizing the potentially racist and sexist content of Crumb’s work, as the same issue features another item by O’Donoghue, “The Vietnamese Baby Book,” which today still retains the ability to shock. (Indeed, it is probably more shocking now than it was in the climate of 1972.) While a publication like National Lampoon parodies Crumb’s success while making visible Crumb’s distinction from mainstream cartooning, some of the first interest in Crumb from the traditional art world came even earlier, in 1969, when an edition of the august British art journal Art and Artists featured an article on American underground comics. In fact, the main focus of the article is Crumb’s compatriot, the equally controversial S. Clay Wilson, and the cover features a violent, blood-soaked, full-color image of Wilson’s pirate characters, with the journal’s title stylized as Art ‘n Artists. The six-page article has more illustrations of Wilson’s work, as well as works by other Zap Comix collective members Victor Moscoso, Gilbert Shelton, and Rick Griffin. Crumb’s importance is acknowledged in the text, where his sex comics are seen as a liberating force. The author, David Zack, comments: “If the matter comes to a fair trial, it would be easy to show Zap, Snatch and Jiz have all sorts of aesthetic value” (1969, 14). He quotes extensively from Crumb’s comics and admires his style, writing, “Zap and Snatch do more than take pop images as high art material, a la Warhol, Indiana, Lichtenstein, Ramos, Thibaud. They extend the scope of popular art” (15). As we will see in due course, some later critics would see them in a different light. Although many fine art critics have continued to value Crumb’s work, some comic historians, fellow cartoonists, and cultural historians have been highly critical of him.

On the other hand, there is little written about Crumb’s way with words. His “Keep on Truckin’” image, its history and influence, are well known, but his work is littered with memorable text from “It’s only lines on paper, folks!” to “More sick humor which serves no purpose.” All of this is delineated in Crumb’s distinctive lettering, a painstaking style with small serif marks on capital letters. The back pages of early issues of Zap Comix display his flair for design, with his lettering playing an important part. The back page of Zap #6 has “Cliffy the Clown” explaining: “You can help to solve the overpopulation problem this quick, easy way! This year, why not COMMIT SUICIDE!?” Below a leering clown face, that last line is executed in large, rounded letters, picked out in red. With a red explosion carrying the message “Too many people!” and several different lettering styles and sizes, the page is both attention grabbing and classically designed. Indeed, Crumb’s comic pages are similar in that he nearly always uses a simple layout of six to eight pages, delineated in a shaky, hand-drawn line. The page designs he creates are made up of positive use of white space, solid blacks, and his usual cross-hatching. The overall effect is to allow the drawings to breathe, at the same time creating a satisfying and balanced pattern design across the whole page.

In the early part of his career, Crumb’s influence was felt outside the field of comics—it extended to the whole field of graphics. In 1971, Print magazine published an article titled “The Critique of Pure Funk” by Patricia Dreyfus, with a classic image of Fritz the Cat fondling his girlfriend above the title. Dreyfus describes “Funk” as “the kind of layout, drawing or photograph that makes the viewer gasp, with delight or disgust, ‘They can’t be serious!’” (1971, 13). Dreyfus interviewed a series of designers, who attributed this new aesthetic to the influence of underground comics and Crumb in particular. Peter Bramley of Cloud Studio commented: “Comix tell you about how people really feel. R. Crumb is into the mundane—you know, garbage and gas stations—but it’s still about people living together and relating to each other” (Dreyfus 1971, 62). Michael Gross, art director for National Lampoon, added: “We like to shake people up—it’s a kind of Lenny Bruce attitude; the shock makes it even funnier” (Dreyfus 1971, 63). Other advertising images in the article show a range of influences. Even if advertisements or humor occasionally water down the shocking content of some underground comics, the impact of Crumb (in particular) and his peers is evident. Marks have meaning, and Crumb’s drawing style amounts to a “statement” even before the content of his work is examined in more detail; advertisers can claim countercultural connections just by appropriating an underground drawing style.

ART AND COMICS IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

After the underground boom died away, only a handful of artists were able to remain in the public eye. Crumb, perhaps along with Art Spiegelman, are rare examples of comic-book artists who achieved a wider cultural and artistic significance in the late twentieth century than is normal in the field. Bart Beaty and Benjamin Woo have pointed out that Crumb holds a unique position for a comic book artist, writing: “On the basis of specifically art-world prestige, Crumb is an elite cartoonist” (2016, 39). Beaty and Woo further argue that, although Crumb has this status in the art world, he is less studied in academic terms by comics scholars than some other artists, in particular Art Spiegelman and Alison Bechdel. The reasons for this, they believe, are twofold: “First, … Crumb works almost exclusively in shorter forms. Second, the interpretive strategies that are dominant in humanistic studies of culture are confounded by the deeply troubling content of much of Crumb’s work” (30).

Beaty and Woo summarize their argument thus: “Unlike his friend Art Spiegelman, who is celebrated for a few great works (well, really one), Crumb is celebrated as a total artist.… Spiegelman may be known for producing Maus, but Robert Crumb is known for producing R. Crumb, and in the art world that makes all the difference” (41). They establish that figures who have produced one well-regarded graphic novel are the most written-about artists from a comics scholars’ point of view (mainly artists, but with the addition of one writer, Alan Moore). Crumb’s status, however, depends on both the catalogue raisonné–like publishing of his entire oeuvre by Fantagraphics Books, and the high prices achieved by his original artwork. The art world appears to be more forgiving of Crumb’s sometimes controversial subject matter, and in Europe, in particular, he has been well regarded for some time. Part of this is due to how Crumb’s work has been placed in fine arts traditions.

Brandon Nelson, although he recounts some problems with Crumb’s imagery, sees elements in Crumb’s work that relate to surrealism: “[T]he fetishized female bodies that so preoccupy Crumb … are turned over and around, folded and twisted and bent.…Salvador Dali is a highly visible precursor to

Crumb’s use of the female form, as seen in such works as Le Rêve” (2017, 152). For Ian Buruma, “his graffiti-like caricatures of animal greed and cruel lust in twentieth century America are closer to George Grosz than any artist I can think of. Like Grosz, Crumb is a born satirist, who brandishes his pencil like a stiletto. But he is funnier than the German artist, and wackier” (2006, 26).

However Crumb’s later work has not always been to the liking of scholars and critics. Despite Crumb’s pride in not selling out, he was again accused of this because of his 2009 Book of Genesis. In an interview, comics historian Paul Gravett pointed out to Crumb that “[a]mong the reviews of your Book of Genesis, Michel Faber in the Guardian wrote that it comes across as the fruits of indentured drudgery” (Gravett 2012). Crumb responded: “It sure felt like indentured drudgery when I was working on it,” and in another interview he explained, “Well, the truth is kind of dumb, actually. I did...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: R. Crumb in Comics History

- I. Aesthetics of the Underground

- II. Political Imaginaries

- III. Cartoons of Scripture, Self, and Society

- IV. The Fine Art of Comics

- Selected Bibliography of Works by R. Crumb

- Contributors