Graphene-based 3D Macrostructures for Clean Energy and Environmental Applications

- 440 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Graphene-based 3D Macrostructures for Clean Energy and Environmental Applications

About this book

With escalating global population, increased consumption of fossil fuels, spiralling energy demand, rapid environmental degradation and global climate change, energy and environmental issues are receiving considerable attention worldwide from the purview of sustainable development. In order to address these complex and interlinked challenges, the development of new materials for affordable green energy technologies (batteries, supercapacitors, fuel cells and solar cells) and environmental remediation methods (adsorption, photocatalysis, separation, and sensing) is essential. Three-dimensional graphene-based macrostructures (3D GBMs) are of great interest in these applications given their large surface area and adaptable surface chemistry.

Graphene-based 3D Macrostructures for Clean Energy and Environmental Applications provides a critical and comprehensive account of the recent advances in the development and potential applications of high performance 3D GBMs for tackling global energy and environmental issues in a sustainable manner. Particular attention is paid to the fabrication schemes, modulation of physiochemical properties, and their integration into practical devices, and the roles of surface chemistry and pore morphology, as well as their interplay, on the overall performance of 3D GBMs are examined.

With contributions from authors around the world this book is a useful resource for both environmental scientists interested in sustainable energy and remediation solutions and materials scientists interested in applications for 3D GMBs.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

*E-mail: [email protected]

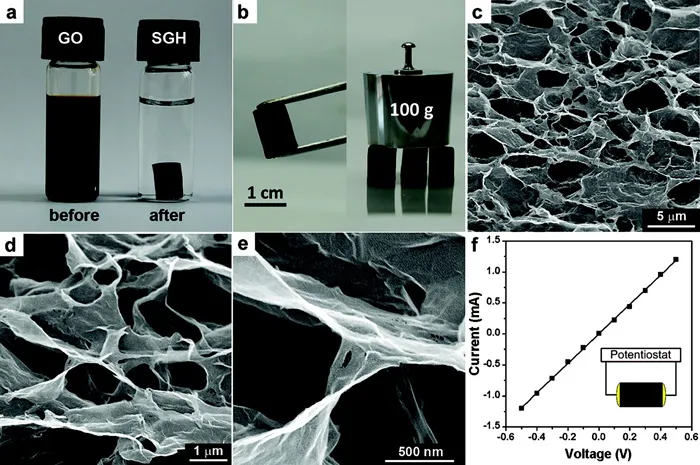

Graphene aerogels are promising materials for the next generation of energy and environmental technologies. They exhibit good electrical conductivity, large surface areas, extraordinary mechanical properties, and as composites can possess a wide range of novel functionalities. However, in order to truly harness their potential, one must understand how the design and assembly of these 3D graphene networks impact their final properties. In this chapter, we explore the various types of graphene-based aerogels reported to date and how their architecture impacts their ultimate performance.

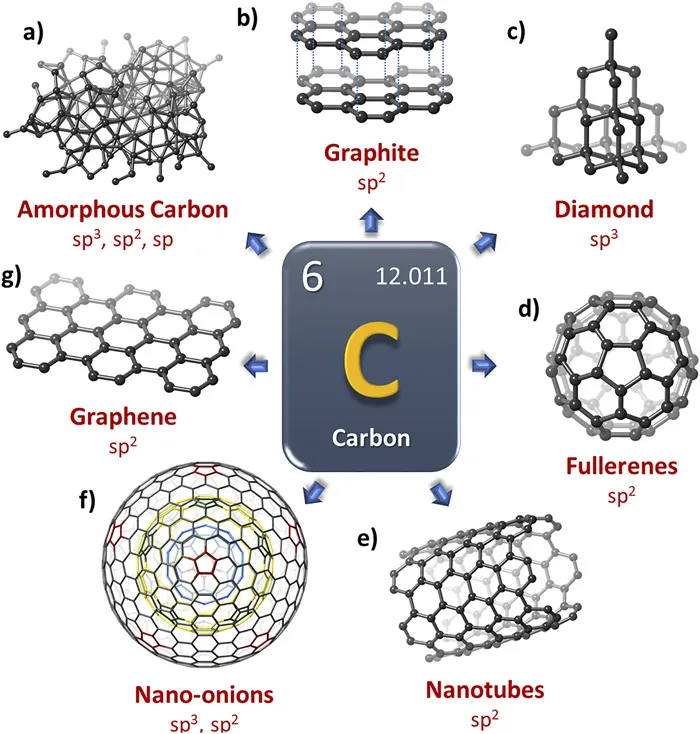

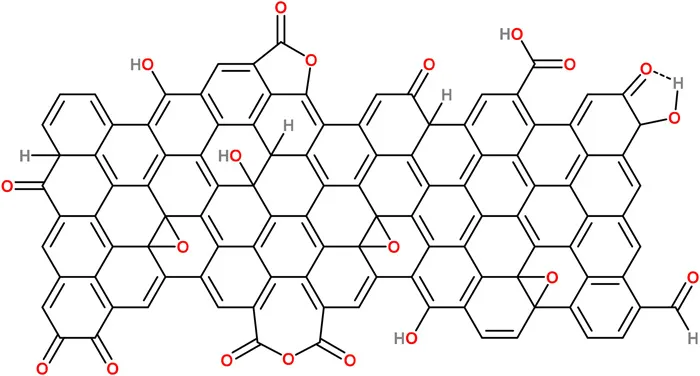

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Graphene Aerogels

1.2.1 Sol–Gel Hydrogels, Freeze-drying, Gelation Methods

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Preface

- Contents

- Chapter 1 Engineering the Architecture of 3D Graphene-based Macrostructures

- Chapter 2 Structure–Property Relationships in 3D Graphene-based Macrostructures

- Chapter 3 Flexible 3D Graphene-based Electrodes for Ultrahigh Performance Lithium Ion Batteries

- Chapter 4 3D Graphene-based Materials for Enhancing the Energy Density of Sodium Ion Batteries

- Chapter 5 Ultrafast Charging Supercapacitors Based on 3D Macrostructures of Graphene and Graphene Oxide

- Chapter 6 3D GBM-supported Transition Metal Oxide Nanocatalysts and Heteroatom-doped 3D Graphene Electrocatalysts for Potential Application in Fuel Cells

- Chapter 7 3D Graphene-based Scaffolds with High Conductivity and Biocompatibility for Applications in Microbial Fuel Cells

- Chapter 8 Highly Efficient Dye-sensitized Solar Cells with Integrated 3D Graphene-based Materials

- Chapter 9 Fuelling the Hydrogen Economy with 3D Graphene-based Macroscopic Assemblies

- Chapter 10 Harvesting Solar Energy by 3D Graphene-based Macroarchitectures

- Chapter 11 3D Graphene-based Macrostructures as Superabsorbents for Oils and Organic Solvents

- Chapter 12 Fast and Efficient Removal of Existing and Emerging Environmental Contaminants by 3D Graphene-based Adsorbents

- Chapter 13 Freestanding Photocatalytic Materials Based on 3D Graphene for Degradation of Organic Pollutants

- Chapter 14 3D Graphene-based Macroassemblies for On-site Detection of Environmental Contaminants

- Chapter 15 Graphene-based Macroassemblies as Highly Efficient and Selective Adsorbents for Postcombustion CO2 Capture

- Chapter 16 Artificial Photosynthesis by 3D Graphene-based Composite Photocatalysts

- Subject Index