Cleaning Data for Effective Data Science

Doing the other 80% of the work with Python, R, and command-line tools

- 498 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Cleaning Data for Effective Data Science

Doing the other 80% of the work with Python, R, and command-line tools

About this book

Think about your data intelligently and ask the right questions

Key Features

- Master data cleaning techniques necessary to perform real-world data science and machine learning tasks

- Spot common problems with dirty data and develop flexible solutions from first principles

- Test and refine your newly acquired skills through detailed exercises at the end of each chapter

Book Description

Data cleaning is the all-important first step to successful data science, data analysis, and machine learning. If you work with any kind of data, this book is your go-to resource, arming you with the insights and heuristics experienced data scientists had to learn the hard way.

In a light-hearted and engaging exploration of different tools, techniques, and datasets real and fictitious, Python veteran David Mertz teaches you the ins and outs of data preparation and the essential questions you should be asking of every piece of data you work with.

Using a mixture of Python, R, and common command-line tools, Cleaning Data for Effective Data Science follows the data cleaning pipeline from start to end, focusing on helping you understand the principles underlying each step of the process. You'll look at data ingestion of a vast range of tabular, hierarchical, and other data formats, impute missing values, detect unreliable data and statistical anomalies, and generate synthetic features. The long-form exercises at the end of each chapter let you get hands-on with the skills you've acquired along the way, also providing a valuable resource for academic courses.

What you will learn

- Ingest and work with common data formats like JSON, CSV, SQL and NoSQL databases, PDF, and binary serialized data structures

- Understand how and why we use tools such as pandas, SciPy, scikit-learn, Tidyverse, and Bash

- Apply useful rules and heuristics for assessing data quality and detecting bias, like Benford's law and the 68-95-99.7 rule

- Identify and handle unreliable data and outliers, examining z-score and other statistical properties

- Impute sensible values into missing data and use sampling to fix imbalances

- Use dimensionality reduction, quantization, one-hot encoding, and other feature engineering techniques to draw out patterns in your data

- Work carefully with time series data, performing de-trending and interpolation

Who this book is for

This book is designed to benefit software developers, data scientists, aspiring data scientists, teachers, and students who work with data. If you want to improve your rigor in data hygiene or are looking for a refresher, this book is for you.

Basic familiarity with statistics, general concepts in machine learning, knowledge of a programming language (Python or R), and some exposure to data science are helpful.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

1

Tabular Formats

Tidy datasets are all alike, but every messy dataset is messy in its own way.–Hadley Wickham (cf. Leo Tolstoy)

import *, we do so here to bring in many names without a long block of imports:from src.setup import * %load_ext rpy2.ipython %%R library(tidyverse) Tidying Up

After every war someone has to tidy up.–Maria Wisława Anna Szymborska

- Tidiness and database normalization

- Rows versus columns

- Labels versus values

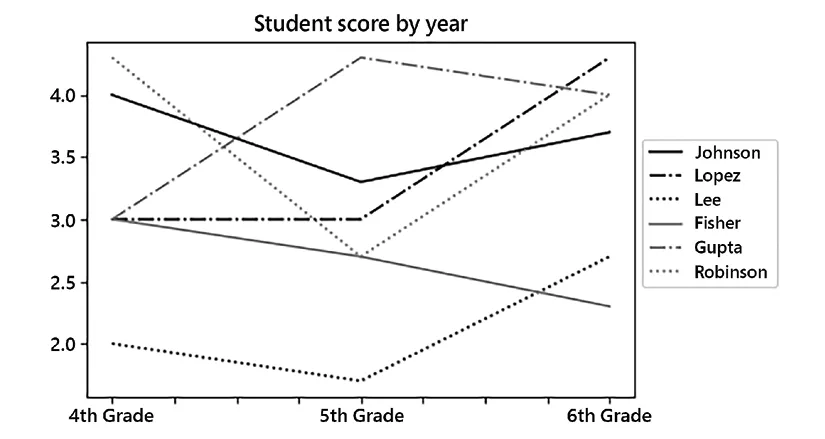

students = pd.read_csv('data/students-scores.csv') students Last Name First Name 4th Grade 5th Grade 6th Grade 0 Johnson Mia A B+ A- 1 Lopez Liam B B A+ 2 Lee Isabella C C- B- 3 Fisher Mason B B- C+ 4 Gupta Olivia B A+ A 5 Robinson Sophia A+ B- A # Generic conversion of letter grades to numbers def num_score(x): to_num = {'A+': 4.3, 'A': 4, 'A-': 3.7, 'B+': 3.3, 'B': 3, 'B-': 2.7, 'C+': 2.3, 'C': 2, 'C-': 1.7} return x.map(lambda x: to_num.get(x, x)) (students .set_index('Last Name') .drop('First Name', axis=1) .apply(num_score) .T .plot(title="Student score by year") .legend(bbox_to_anchor=(1, .75)) );

DataFrame.melt() method can perform this tidying. We pin some of the columns as id_vars, and we set a name for the combined columns as a variable and the letter grade as a single new column. This Pandas method is slightly magical and takes some practice to get used to. The key thing is that it preserves data, simply moving it between column labels and data values:students.melt( id_vars=["Last Name", "First Name"], var_name="Level", value_name="Score" ).set_index(['First Name', 'Last Name', 'Level']) First Name Last Name Level Score Mia Johnson 4th Grade A Liam Lopez 4th Grade B Isabella Lee 4th Grade C Mason Fisher 4th Grade B ... ... ... ... Isabella Lee 6th Grade B- Mason Fisher 6th Grade C+ Olivia Gupta 6th Grade A Sophia Robinson 6th Grade A 18 rows × 1 columns %%R library('tidyverse') studentsR <- read_csv('data/students-scores.csv') studentsR ── Column specification ──────────────────────────────────────...Table of contents

- Preface

- PART I: Data Ingestion

- PART II: The Vicissitudes of Error

- PART III: Rectification and Creation

- PART IV: Ancillary Matters

- Why subscribe?

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app