eBook - ePub

John Sayles

About this book

John Sayles is the very paradigm of the contemporary independent filmmaker. By raising much of the funding for his films himself, Sayles functions more independently than most directors, and he has used his freedom to write and produce films with a distinctive personal style and often clearly expressed political positions. From The Return of the Secaucus Seven to Sunshine State, his films have consistently expressed progressive political positions on issues including race, gender, sexuality, class, and disability.

In this study, David R. Shumway examines the defining characteristic of Sayles's cinema: its realism. Positing the filmmaker as a critical realist, Shumway explores Sayles's attention to narrative in critically acclaimed and popular films such as Matewan, Eight Men Out, Passion Fish, and Lone Star. The study also details the conditions under which Sayles's films have been produced, distributed, and exhibited, affecting the way in which these films have been understood and appreciated. In the process, Shumway presents Sayles as a teacher who tells historically accurate stories that invite audiences to consider the human world they all inhabit.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

John Sayles |

Critical Realist

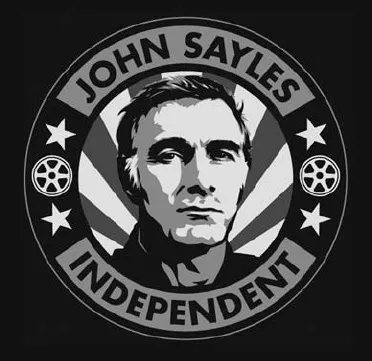

John Sayles: Independent

The one word most often associated with John Sayles is independent. He has been throughout most of his career referred to as America’s leading independent filmmaker. More recently, he has been called both the grandfather and the godfather of American independent cinema. He may be the only filmmaker in the world whose face appears on a seal or medallion. This medallion graces the first page of johnsayles.com, and has appeared after the credits of some of his films. It shows a drawing of Sayles’s face, with a legend imprinted around the outside: at the top, “John Sayles,” and at the bottom, “Independent” (see figure 1). This designation describes Sayles’s relationship to the film industry accurately. He has made only one film within the traditional Hollywood system, where the studio, rather than the director, retains control over casting and cutting.

Figure 1. A symbol of independence: the John Sayles Medallion, from johnsayles.com. |

Sayles’s own definition of independence is not, however, focused on the relationship of a film to the industry:

No matter how it’s financed, no matter how high or low the budget, for me an independent film emerges when filmmakers started out with a story they wanted to tell and found a way to make that story. If they ended up doing it in the studio system and it’s the story they wanted to tell, that’s fine. If they ended up getting their money from independent sources, if they ended up using their mother’s credit cards, that doesn’t matter. (Carson, “Independent” 129).

Sayles therefore considers Martin Scorcese, Spike Lee, Oliver Stone, and Tim Burton independents despite the fact that they have all made movies within the studio system (Smith 250–51). Like them, Sayles has consistently found ways to make the stories he wants to make, though one might add that because of those stories, he has a greater struggle to make them.

Yet, there is something also misleading about the way in which “independent” seems to have become almost a part of Sayles’s name. Sayles no more makes films by himself than did Howard Hawks or John Ford. Indeed, there is no director more conscious of the fact that film is a collaborative medium. In discussing his work in interviews, he always speaks of “our film,” not “my film.” Those who have worked with him describe the relations on a shoot, not as a hierarchy, but as a community, where the various participants are treated in an egalitarian manner. The image of rugged individualism, which the “independent” label seems to carry, is antithetical to Sayles’s practice and to his vision.

Sayles’s association with independent cinema also accurately reflects his pioneering role in a movement that developed beginning around 1980 and that might be said to have recently come to an end. As Yannis Tzioumakis has shown, there has always been an independent film sector, in which he includes, for example, producer David O. Selznick in the late 1930s and early 1940s, the production company Walt Disney Pictures in the 1930s, and United Artists as a distributor of independent films from its inception in 1920 until it was sold to a conglomerate in 1967. In the 1960s, major hits like The Graduate (Mike Nichols, 1967) and Easy Rider (Dennis Hopper, 1969) were produced by entities other than the major studios. But the meaning of the term “independent” had shifted by the end of the 1970s, in part because the industry had consolidated, with film production now controlled by a handful of conglomerates—and in part because of production trends within these companies that focused on making megaprofits on blockbusters like Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975) and Star Wars (George Lucas, 1977). Film had long been an industrial commodity, and during the 1970s, it seemed to become all the more so. But even as the average cost of a Hollywood film was increasing exponentially, the amount of money required to make a movie was actually declining as equipment became less expensive and more readily available.

While avant-garde filmmakers such as Stan Brackage and Jonas Mekas had long made films without the benefit of a production company, very few narrative films were made that way. Sayles’s most significant predecessor was John Cassavetes, who beginning with Shadows in 1959, wrote, directed, and sometimes edited low-budget and aesthetically innovative films funded by the money he made acting in studio productions. In 1974, he set up his own distribution company, Faces International, to distribute A Woman under the Influence when he could not find another company willing to take on the film. Cassavetes’s commitment to his own vision was a model for many of the auteurs of 1970s, such as Martin Scorcese, and Sayles has called him a major influence.

When Sayles made his first film, Return of the Secaucus Seven, he has said that there were four companies that were in the business of distributing films made outside of mainstream Hollywood (quoted in Anderson). Getting an independent film distributed to theaters was so unusual that Sayles thought his film’s best chance to be seen was probably on Public Television, and he consciously shot the film with the small screen in mind. The film’s surprising success at the box office and enthusiastic critical reception demonstrated the viability of this new mode of filmmaking. New distributors emerged to handle an increasing number of films made outside of the industry. These films often produced a good return on their small investments, and were thus attractive from a business perspective. The trend culminated in the transformative success of sex, lies, and videotape (Steven Soderbergh, 1989), which a small independent company called Miramax acquired after its screening at the Sundance Film Festival. The film’s $24 million gross on a $1.2 million cost made independent film something the studios wanted, and they created or acquired divisions to distribute and eventually produce them—rendering, of course, the economic meaning of “independent” moot.

Because Sayles has been defined by his position outside of the industry, in what follows I am attentive to issues of finance and distribution. Although a study of a director who has not been so defined might reasonably ignore his or her position in the market, one cannot deal with Sayles accurately without considering his struggles with financing and distributing his work. I therefore discuss the financing, distribution, and reception of Sayles’s films, using the best information available. The point of this is certainly not to buy into the current obsession with box-office performance as a measure of a film’s worth, but to make clear the conditions under which Sayles’s films have been produced and exhibited, conditions which have affected the way in which these films have been understood and appreciated.

During the 1980s, however, another meaning of the term “independent” emerged that was rooted in “the kinds of formal/aesthetic strategies they adopt” rather than economics and their relationship to the broader social, cultural, political or ideological landscape (King 2). For some scholars, formal considerations seem to be most important. So, when Juan Suárez observes, “[Jim] Jarmusch has often been regarded as the main exponent of independent cinema in the 1980s and 1990s,” it is clearly because of the innovative form his films display (6). Suárez points out that the influence of Jarmusch’s films can be seen in the work of Hal Hartley, Sofia Coppola, and Richard Linklater, among others, while Sayles, though often cited as an inspiration by other aspiring filmmakers, does not seem to have been much copied. Others identified as leading independents, including Todd Haynes, Kevin Smith, Gus Van Sant, and Soderbergh, exemplify the sense of “independent” as a filmmaker who experiments with narrative, visual form, or genre, regardless of how the film is financed.

Sayles’s critical stance toward American society and its politics is the defining characteristic of his cinema, but that stance has not been expressed through the stylistic experimentation often thought to be required for it. Radical politics are attributed to Jarmusch and Haynes in part because of their style. Sayles has said, “I’m totally uninterested in form for its own sake. But I am interested in story-telling technique” (Smith 100). That distinction is reinforced by his way of discussing his own films in interviews and DVD commentaries, where his concern is mainly how the story got told. He thinks of himself as an artisan or craftsperson, but not as an artist or the maker of “art films.” In this sense, Sayles has much in common with studio era directors such as Howard Hawks, who also conceived of themselves as craftsmen and storytellers.

In answering a question about style posed by interviewer Gavin Smith, Sayles offered a longish discussion of Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, and the new journalism, where he asserted, “I was never interested in it, because I felt that the article wasn’t about this actor or this singer or this politician. The article was about Tom Wolfe, about Gay Talese” (101). This suggests that Sayles wants his audience not to be thinking about him, but about the events and characters he is presenting. The answer also implies that Sayles feels a kinship with traditional journalists who give you the story, not their own personalities. Sayles’s visual style, then, is always at the service of his story, and he is on occasion visually inventive when the story demands it. He is much more innovative in his narrative structures, which often deviate from standard Hollywood formulas. Yet because “independent” cinema since Cassavetes has been associated with style rather than story, Sayles may be subject to expectations he has no desire to fulfill.

John Sayles: Realist

When Sayles is called a realist in the press, it is usually expressed as the Los Angeles Times did in 1995, calling him a “master of gritty realism and champion of the American working class” (Black in Carson, Interviews 171). Realism here means a particular kind of content, and that content is connected to a traditionally leftist position of support for workers. These are both aspects of Sayles’s realism, but many of his films are neither gritty nor are focused on a particular class. Sayles’s realism is much broader, including his focus on story and character and his commitment to the idea that film can tell us something about the world out of cinema. Sayles has said, “I always want people to leave the theater thinking about their own lives, not about other movies” (Vecsey in Carson, Interviews 96). The desire to make films that make people think about their own lives gets at the essence of the director’s realism. What Sayles says he learned from Cassavetes’s films was “that you could have recognizable human behavior on the screen” (Smith 51). Whereas film theory and at least some film practice have since the 1970s called into question is the whole idea of realism in cinema, Sayles has never wavered from his ambition to tell us the truth about the world beyond the screen using various means available to the makers of fictions. In arguing that Sayles is best understood as a “critical realist,” I’m disagreeing with Mark Bould, who in his study of Sayles holds that “he has been long engaged in developing American naturalist filmmaking” (6). Bould compares Sayles to Zola, in that the filmmaker’s narrative method tends to present social problems “as social facts, as results, as caput mortuum of a social process,” as Georg Lukács complained about the French naturalist (“Narrate or Describe?” 113–14). Sayles has been influenced by the American naturalist tradition, especially through the work of Nelson Algren, which he cites as an early influence on his fiction. But his films do not reveal a commitment to naturalism as an artistic form or as an ideology, lacking entirely any sense of the predetermined decline of individuals not possessed of the strongest traits. Sayles may often seem pessimistic, but this is better explained by Antonio Gramsci’s maxim, “pessimism of intellect, optimism of the will,” than it is by attributing to him a secret belief in biological determinism. Sayles’s characters are never merely spectators, as Lukács believes Zola’s are, but are always engaged in a struggle with the reality they confront. Still, political projects are meaningless without hope, since only a possibility of success, however limited or remote, makes such projects rational endeavors. Sayles’s films never express complete hopelessness, but there are instances, which I discuss later, where their pessimism of the intellect comes close to negating any optimism of the will.

Lukács asserts, “The central aesthetic problem of realism is the adequate presentation of the complete human personality” (Studies 7). This is a view that Sayles might well share, because his films are peopled by an enormous range of characters and he strives to make them full-rounded. He takes his film characters so seriously that he writes biographies of them for his actors to read. And like the great Hungarian critic, Sayles understands that the human personality exists only within a definite social order. His films always give us characters who live in a particular time and place, belong to a recognizable class, and have a specific social role—almost always including work. But there are limits to how much a more or less orthodox Marxist like Lukács can enlighten us about the realism of a filmmaker who, whatever his personal relationship to the Marxist tradition, clearly does not regard it as the final truth about history and society. Lukács, the Hegelian Marxist, believed that it was possible to know society as a totality, and he believed that realists like Honoré de Balzac presented both human beings and society as “complete entities” (Studies 6). Sayles is skeptical of all claims to completeness, and would surely not claim it for any of his films. He may indeed accept the notion that society is a whole, but as a filmmaker all he can do is give us different perspectives or experiences of it. Unlike Lukács, Sayles brings no overarching preconception about the nature of reality to his films, assuming neither that history is a dialectical march toward utopia, nor that the current social arrangements are natural and inevitable.

Much of the formal experimentation featured in the independent films of the 1980s and 1990s is antirealist. It is hard to imagine that antirealist film theory, and the antirealism of poststructuralism more generally, did not have some influence on this trend. The 1970s critique of realism derived from poststructuralism, especially from Roland Barthes’s dismissal of the referentiality of the text. For Barthes, what is of interest is not what a text can tell us about a world it claims to represent, but rather what it tells us about writing and reading—that is about itself and other texts. Thus in S/Z, Barthes asserts, “It is necessary to disengage the text from its exterior and its totality” (Quoted in MacCabe, “Realism” 140). If Barthes’s position is extreme, it is not atypical of modernist and postmodernist criticism, which has consistently been skeptical of representation and which has read works of art primarily in terms of their relations to other works of art.

The critique that film theory made of Classical Hollywood cinema held that the process of making films seemed to be a transparent window on reality, the films offering the illusion of realism, i.e., an objective representation of reality, instead of the ideologically inflected representation it actually presented. Perhaps the most influential theorist of realism in film was Colin MacCabe. Like modernist critics of realism, he associated it with empiricism, but for him the chief problem was not realism’s naïveté or lack of complexity, but its silent transmission of ideology. Hollywood films were seen as covertly ideological, and their realism was understood as an aspect of the false consciousness they were accused of purveying. This critique was applied to most fiction films, which were deemed realist despite the rather obvious unreality of many of them. The notion of Hollywood as a “dream factory” that triumphed by selling patent escapism largely disappeared from film studies at this time. “Realism” in 70s film theory was often called bourgeois, an assertion of a deep ideological connection between the form of Hollywood film and the ruling class that produced it.

Realism was not only accused of ignoring the fact of filmic mediation, but of claiming to present a complete picture of the world that was itself complete and without contradiction. Thus MacCabe argued that realism denies the viewer access to “contradictory positions available discursively to the subject” (64). The realist film offers a single point of view, for which it claims perfection, and which offers to the viewer an “imaginary plentitude” (67). Curiously then, this New Left criticism is attacking realism for doing exactly what Lukács claimed it ought to do, present the social totality. Lukács thought that realism presented the contradictions existing in society, while MacCabe wanted films that acknowledged the contradictions of discourse about society.

One of the effects of illusionistic realism was that style had to be subordinated to narrative so that the audience would focus only on the story and not think about the way it was presented to them. According to Robert Ray, “The ideological power of Classic Hollywood’s procedure is obvious: under its sponsorship, even the most manufactured narratives came to seem spontaneous and ‘real.’ A spectator prevented from detecting style’s role in a mythology’s articulation could only accede to that mythology’s ‘truth’” (55). Film theorists therefore argued that anything that disrupted the illusion of realism, especially any violation of standard Hollywood visual conventions, could be construed as an act of resistance. Such violations would expose the supposed natural form of cinema as arbitrary and ideologically determined.

Sayles’s work would seem to represent a solid rebuke to this attack on realism. His films are not only realist in intention, but by conscious design they subordinate style to narrative. Sayles’s films suggest that the ideological work of Hollywood was not a function of its form, its failure to call attention to its own mediation, but to its narrow, affirmative vision, especially during the years of the production code. He sees the problem not as one of cinematic language, but of cinematic content. He might accept the idea that Hollywood films present a partial view of the world as if it were complete, but his answer to that is to show what is missing. His films depict a world quite different from “the cinema of affluence” of contemporary Hollywood (O’Sullivan in Carson, Interviews 87). Sayles’s realism shows us a world that we are not expecting and in which we may not feel comfortable.

A significant element o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- John Sayles: Critical Realist

- Interviews With John Sayles

- Filmography

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access John Sayles by David R. Shumway in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film Direction & Production. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.