- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

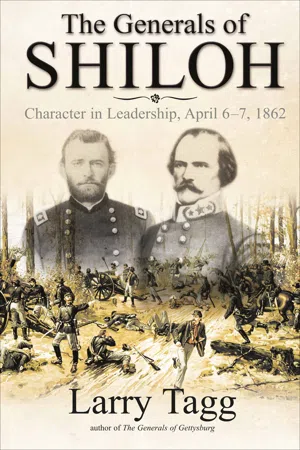

About this book

The author of

The Generals of Gettysburg examines the characters and actions of the military leadership at this Tennessee Civil War battle.

"Character is destiny," wrote the Greek philosopher Heraclitus more than twenty-five centuries ago. Most writers of military history stress strategy and tactics at the expense of the character of their subjects. Larry Tagg remedies that oversight with The Generals of Shiloh, a unique and invaluable study of the high-ranking combat officers whose conduct in April 1862 helped determine the success or failure of their respective armies, the fate of the war in the Western Theater, and, in turn, the fate of the American union.

Tagg presents detailed background information on each of his subjects, coupled with a thorough account of each man's actions on the field of Shiloh and, if he survived that battle, his fate thereafter. Many of the great names are found here in this early battle, from Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman, and Don Carlos Buell to Albert S. Johnston, Braxton Bragg, and P. G. T. Beauregard. Many more men, whose names crossed the stage of furious combat only to disappear in the smoke on the far side, also populate these pages. Each acted in his own unique fashion. This marriage of character ("the features and attributes of a man") with his war record offers new insights into how and why a particular soldier acted a certain way, in a certain situation, at a certain time.

Nineteenth century combat was an unforgiving cauldron. In that hot fire some grew timid and listless, others demonstrated a tendency toward rashness, and the balance rose to the occasion and did their duty as they understood it. This book explores all of their individual stories.

"Does a good job of shining a bright light upon the great preponderance of highly placed citizen-generals in the Shiloh armies." — Civil War Books and Authors

"Character is destiny," wrote the Greek philosopher Heraclitus more than twenty-five centuries ago. Most writers of military history stress strategy and tactics at the expense of the character of their subjects. Larry Tagg remedies that oversight with The Generals of Shiloh, a unique and invaluable study of the high-ranking combat officers whose conduct in April 1862 helped determine the success or failure of their respective armies, the fate of the war in the Western Theater, and, in turn, the fate of the American union.

Tagg presents detailed background information on each of his subjects, coupled with a thorough account of each man's actions on the field of Shiloh and, if he survived that battle, his fate thereafter. Many of the great names are found here in this early battle, from Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman, and Don Carlos Buell to Albert S. Johnston, Braxton Bragg, and P. G. T. Beauregard. Many more men, whose names crossed the stage of furious combat only to disappear in the smoke on the far side, also populate these pages. Each acted in his own unique fashion. This marriage of character ("the features and attributes of a man") with his war record offers new insights into how and why a particular soldier acted a certain way, in a certain situation, at a certain time.

Nineteenth century combat was an unforgiving cauldron. In that hot fire some grew timid and listless, others demonstrated a tendency toward rashness, and the balance rose to the occasion and did their duty as they understood it. This book explores all of their individual stories.

"Does a good job of shining a bright light upon the great preponderance of highly placed citizen-generals in the Shiloh armies." — Civil War Books and Authors

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Generals of Shiloh by Larry Tagg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Army of the Tennessee

Major General

Ulysses Simpson Grant

On the day Fort Sumter fell, Ulysses “Sam” Grant was working as a clerk at his family’s leather goods store in his hometown of Galena, in the remote northwest corner of Illinois. Grant had lived in the town for less than a year and few people knew him. But because of his West Point education and 15-year career in the Army, a few townsmen persuaded him to preside over a Union rally two days later.

At the rally, Congressman Elihu Washburne and attorney John Rawlins gave stirring speeches and inspired enough enlistments to fill a full 100-man company from Galena. Afterward, the congressman made a point of seeking out Grant, intrigued that in his hometown there lived a West Pointer and Mexican War officer whom he did not know. Washburne was immediately impressed with Grant, whose ideas on politics and the organizing and equipping of the new Union regiments were already well developed.

Grant never returned to the family store. He spent the next two weeks drilling and uniforming Galena’s new infantry company, although he declined to be its captain in order to remain available for a higher post. When the company went to Springfield for mustering-in, he went with it. After the Galena men boarded a train for Cairo, Illinois, with the 11th Illinois Infantry regiment on April 30, Grant was invited by Governor Richard Yates (who had heard about Grant from Washburne) to remain in the state capital, without rank but with the duty of organizing and mustering in new Illinois regiments.

Grant drew notice by doing his job ably and without fanfare, and Governor Yates (again, after conferring with Washburne) named Grant as colonel of the new 21st Illinois Infantry on June 15, 1861. Grant’s regiment was assigned to guard a railway line in northern Missouri. Grant marched his regiment toward Missouri on July 3, and for the next six weeks, he earned valuable experience as the colonel of a regiment in the volunteer army. Perhaps his greatest epiphany came on July 14, after he had received orders to seek out and destroy a Confederate regiment under Col. Thomas Harris. As he approached the Rebel camp, Grant remembered later, “My heart kept getting higher and higher until it felt to me as though it was in my throat. I would have given anything then to have been back in Illinois, but I had not the moral courage to halt and consider what to do.” When he found the enemy camp abandoned, Grant wrote:

My heart resumed its place. It occurred to me at once that Harris had been as much afraid of me as I had been of him. This was a view of the question I had never taken before; but it was one I never forgot afterwards. From that event to the close of the war, I never experienced trepidation upon confronting an enemy, though I always felt more or less anxiety. I never forgot that he had as much reason to fear my forces as I had his.

During Grant’s tenure at the head of the 21st Illinois in northern Missouri, on July 25 Abraham Lincoln appointed John C. Fremont to command the Western Department. A week or so later came news that Lincoln had created 34 new brigadiers to lead the new brigades of the Union army. For political reasons, he had parceled generalships out to states in the same manner as postmasterships and other Federal appointments. Illinois was entitled to four generals, to be chosen by the Illinois congressmen. The first one was given to Grant, at the request of Lincoln’s and Grant’s mutual friend, Elihu Washburne. (The other three were Stephen A. Hurlbut, Benjamin M. Prentiss, and John A. McClernand—all of whom would be division commanders under Grant nine months later at the battle of Shiloh.)

Fremont ordered Grant to assume command of the District of Southeast Missouri, with its tiny force of three regiments, headquartered at Cairo, Illinois. Although Fremont would say later that he recognized Grant’s “dogged persistence” and “iron will,” he almost certainly did not realize the significance of his choice. On September 1, 1861, Grant took the reins of what would soon prove to be the most important district in the West, and began to organize what would be the future Army of the Tennessee.

Aside from the capital at Washington, there was no strategic point valued so highly as Cairo, where the nation’s mightiest rivers, the Mississippi and the Ohio, met, and which pointed downward like a dagger into the junction between two slave states, Kentucky and Missouri. Southern Illinois itself, settled largely by Virginians and Kentuckians, was strongly sympathetic to the Confederate cause. The government’s first act in the West, in the first week after the fall of Fort Sumter, had been to hurry 595 men onto trains in Chicago and speed them to Cairo. One town native wrote, “The importance of taking possession of this point was felt by all, and that, too, without waiting the arrival and organization of a brigade.”

Once there, Grant was immediately and relentlessly aggressive. Col. Theodore Lyman, who worked with him later in the war, wrote, “He habitually wore an expression as if he had determined to drive his head through a brick wall and was about to do it.” From his first days at Cairo, Grant was constantly scheming how to get at the stronger Confederate army camped at Columbus, Kentucky, a day’s march away.

At the same time, Grant was fastidious in his attention to administrative detail, the same trait Congressman Washburne had discovered the previous spring in Galena. From his first days at his new headquarters at Cairo, he was unrelentingly thorough. When Major General Henry Halleck replaced Fremont as head of the Department of the Missouri on November 9, 1861, Halleck, whose strengths were organization and management, was impressed with the tidiness of Grant’s command, and was persuaded to keep Grant on at his post in Cairo.

Grant was one of few Civil War generals who saw value in keeping his men active and giving them their head. He exercised his green recruits by sending them on constant patrols in the swampy lowlands of nearby Missouri and Kentucky. In those restless, watchful fall weeks, his little army operated entirely in this tiny but important tract of land, a semicircle extending south from Cairo with a radius of fifteen miles, with Columbus, Kentucky and Belmont, Missouri—the two Rebel strongpoints straddling the Mississippi River—at its southernmost edge. Grant’s stance was always aggressive, always tugging at the leash, an attitude which he imparted to the men under his command. Here was the major difference between himself and his opposite at Columbus, Confederate General Leonidas Polk, who was content to play a defensive role and “let sleeping dogs lie.” This difference would manifest itself in the fighting mettle of the armies at the great tests of Fort Donelson and Shiloh in the coming winter and spring.

After two months of probes and patrols, the men were spoiling for a fight. To oblige their lust for battle, Grant on November 6, 1861 put 3,500 men in five regiments, plus artillery and cavalry, onto transports, floated them down the Mississippi, landed them on the Missouri shore above Belmont and rode at their head toward the Rebel camp.

After the battle of Belmont that followed, both sides claimed victory, but Grant ever afterward maintained that, by fighting their way through the Rebel line not just once, into the enemy camp, but again, on the way back to their transports, his men gained confidence in their fighting ability, and that their baptism of fire at Belmont steeled them for what lay ahead.

Too, the battle of Belmont showed Grant as a battlefield leader, one his men trusted and loved as a soldier. Part of this derived from his unmatched ability as a horseman—his men loved seeing his grace on a mount—and part from his physical courage. He shared his men’s danger when bullets started to fly, and had a horse shot from under him during the fighting. The men also saw for the first time the indomitability that he showed in battle. He would never incite the wild cheering and hat-waving that George McClellan did back East. Rather, he inspired a quiet loyalty.

Another talent crucial to Grant’s success as a leader of men was his ability, rare among generals, to write clear orders—he spent hours in the evening personally writing out his instructions for the next day’s maneuvers. When he was done with one order, he would push it from the table onto the floor and start on the next. When he went to bed, an orderly would gather up the paper slips and take them to the chief of staff, who would distribute them to his subordinates.

In December 1861, Grant’s tiny District of Southeast Missouri was merged into the District of Cairo, Department of the Missouri. By this time Grant’s command had grown to 16 regiments in four brigades, all clustered in riverfront posts near the junction of the Mississippi and the Ohio.

Early 1862 was a time of frustrating inactivity, east and west. In the nation’s capital, George McClellan was in bed with typhoid fever, and Lincoln did not know what the general’s plans were. Desperate at the impasse, President Lincoln moaned to his quartermaster general, “The bottom is out of the tub! What should I do?” General Halleck in St. Louis responded by ordering a “demonstration” into western Kentucky by Grant’s force at Cairo, in concert with the new “turtles”—175-foot-long armored gunboats with 13 guns each, machines that would revolutionize warfare along the inland rivers. Halleck’s order to move south, even though it was designed only as a feint, was one which the restless Grant eagerly accepted. The expedition went forward on January 14, and, although it accomplished little, it yielded one important result: when the gunboats neared Fort Henry in their ascent of the Tennessee River, they saw that it was weak and poorly sited.

The most promising avenue of advance into the Confederate interior was up the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers. Grant had for weeks been persistently requesting permission to attack Fort Henry, the gateway to the upper Tennessee Valley. In that desolate winter, at the nadir of Union fortunes, Halleck, on January 28, 1862, granted Grant’s request.

On February 1, in preparation for an assault on Fort Henry, Grant transported his newly assembled army of about 15,000 men up the Ohio and Tennessee rivers and had it ashore near Fort Henry by February 5. Leading the column of steam transports up the river were four of the new ironclad gunboats, with three timberclad gunboats for added firepower. As it turned out, the capture of Fort Henry was accomplished the next day entirely by the gunboats while most of the garrison fled. As a result, the Tennessee River was opened to the Union army as far south as Muscle Shoals in northern Alabama.

Grant had already determined to “keep the ball moving” (his words) by advancing on the nearby Fort Donelson, ten miles to the east on the Cumberland River. He held a council of war with his subordinates (the only time in the war he would ever do so), and they voiced unanimous approval of the advance. On February 12, Grant plunged onto the muddy trails to Fort Donelson, the nearby gateway to the Cumberland and thus Nashville and central Tennessee.

There the combined Confederate garrisons of Forts Henry and Donelson, with reinforcements from nearby Tennessee and Kentucky brigades, waited behind their earthworks. In the crucible of the subsequent fighting at Ft. Donelson, Grant showed a willingness to improvise the command structure of his army according to the demands of the battle, improvising a new 3rd Division from regiments that arrived by steamboat during the combat.

Fort Donelson surrendered on February 16, 1862, and Grant was promoted to major general, effective the same day. As the news spread, gloom in the North over the war became euphoria. Grant’s victory had deprived the South of an army of 13,000 Rebel soldiers captured there. Too, it completely collapsed the Confederate front. One week later, Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston, at the head of the main Confederate army in Bowling Green, Kentucky, retreated through Nashville, Tennessee, heading south. A week after that, Polk’s army evacuated the “Gibraltar of the West” at Columbus on the Mississippi.

Halleck, from his office in St. Louis, created a new district, the District of West Tennessee, and made Grant the commander while Grant’s headquarters were still at Fort Donelson. Grant’s new district was unique in that it had no geographical limits, but consisted only in Grant’s forces that were to operate with him on the Tennessee River.

On February 21, Grant reorganized the Army of the District of West Tennessee, now grown to 27,000 men, into four divisions. The 1st, 2nd and 3rd Divisions remained essentially the same as they were at Fort Donelson, and a 4th Division, under Brig. Gen. Stephen Hurlbut, was cobbled together from regiments more recently arrived by steamboat, mostly from Illinois.

Halleck simultaneously decided to create a fifth division for Grant. On February 14, immediately after the capture of Fort Henry, Halleck had given his friend, Brig. Gen. William T. Sherman—who was attempting to rebuild his reputation after being dismissed for “insanity” the previous November—command of a new division based at Paducah, consisting of regiments Halleck was forwarding from all over his department. On March 1, Halleck added it to Grant’s command.

With the latest additions, Grant reported his army’s strength as just under 40,000 men.

On the same day he added Sherman’s division to Grant’s army, Halleck ordered Grant to move his army up the Tennessee River on a raid with the purpose of destroying railroad bridges and telegraph lines vital to Confederate communications in western Tennessee. On March 4, Grant starting marching his forces at Fort Donelson, which then consisted of the 1st, 3rd, and 4th Divisions, back to Fort Henry to embark for the advance up the Tennessee River.

It was not clear that it was any longer Grant’s army to command, however. After the victory at Fort Donelson, he had rushed C. F. Smith’s 2nd Division up the Cumberland River to Clarksville, Tennessee—a leap toward the prize of Nashville. This placed Smith’s division in Don Carlos Buell’s neighboring Department of the Cumberland, and Halleck, always sensitive on the subject of department lines, hit the roof. Repeated misunderstandings in communications between Grant in Tennessee and Halleck at his headquarters in St. Louis—inevitable in the far-flung Western Theater—inflamed Halleck’s petty jealousies now that Grant, the muddy-booted hero of Fort Donelson, was suddenly the nation’s darling. So on March 4, Halleck wired Grant ordering him to hand control of the upcoming Tennessee River operation to Brig. Gen. Charles F. Smith. Halleck told Grant himself to wait behind at Fort Henry.

Smith, now leading the expedition, floated his 2nd Division back down the Cumberland and Ohio rivers, then up the Tennessee to Savannah, Tennessee, the river town closest to the Union army’s next strategic objective: the crucial railroad hub at Corinth, Mississippi, only 34 miles to the southwest. Smith’s flotilla arrived at Savannah in the second week of March, the same week the steamboat fleets bearing Brig. Gen. Lew Wallace’s 3rd Division and Sherman’s 5th Division labored upriver.

It took 24 hours for Sherman’s 5th Division, on 17 steamboat transports, to cover the 100 miles from Paducah to Savannah, where it arrived on March 11.

Wallace’s 3rd Division disembarked on March 12 at Crump’s Landing, on the west bank of the Tennessee a mile or so upriver from Savannah. Wallace occupied the landing with his infantry, then sent his cavalry straight west on an expedition that destroyed the north-south Mobile & Ohio Railroad trestle north of Corinth at Beach Creek. (Within 36 hours, however, the Confederates had repaired the bridge.)

That same week, Halleck’s relentless lobbying of Lincoln for unrivaled authority in the west was rewarded: Lincoln’s “War Order #3” merged the three departments west of the Appalachians into a new Department of the Mississippi under Halleck, and made Brig. Gen. Buell’s Army of the Ohio part of Halleck’s command.

In another development important to the campaign, on March 12 General Smith fell while boarding a skiff at Savannah and cut his shin badly. Brig. Gen. W.H.L. “Will” Wallace replaced him as commander of the 2nd Division, while Grant was reinstated in control of the expedition. In the coming weeks, the seemingly minor injury would fester and kill Smith.

On March 14, Sherman steamed further upriver to accomplish the other bridge-burning mission. He moved his division to the mouth of Yellow Creek, from which he marched south and attempted to torch the Bear Creek bridge on the east-west Memphis & Charleston Railroad. Forced to abandon the movement because of rain and high water, S...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- ARMY OF THE TENNESSEE: Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant

- ARMY OF THE OHIO: Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell

- ARMY OF THE MISSISSIPPI:

- FIRST ARMY CORPS: Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk

- SECOND ARMY CORPS: Maj. Gen. Braxton Bragg

- THIRD ARMY CORPS: Maj. Gen. William J. Hardee

- RESERVE CORPS: Brig. Gen. John C. Breckinridge

- Afterword

- Critical Bibliography

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author