- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

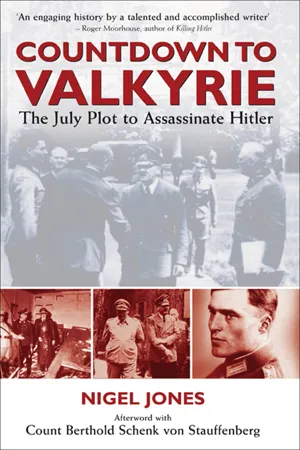

There were over forty plots to assassinate Hitler— This is the "compelling, fast-paced account" of the one that came closest to succeeding (

Publishers Weekly).

The July Plot of 1944 was masterminded by Count Claus von Stauffenberg, a member of the German General Staff, who had been rushed back from Africa after losing his left eye and right hand. For his injuries, he had been decorated as a war hero. However, he'd never been a supporter of Nazi ideology—and he was increasingly attracted by the approaches of the German resistance movement.

After an attempt to assassinate Hitler in November 1943 failed, Stauffenberg developed a new plot to kill him at the Wolf's Lair, fortified underground bunkers, on July 20, 1944. Besides the führer's assassination, Stauffenberg organized plans to take over command of the German forces and sue for peace with the Allies. With the help of photographs, explanatory maps, and diagrams, author Nigel Jones dissects the events leading up to the attempt, the events of the day in minute-by-minute detail, and the aftermath in which the conspirators were hunted down. No other work on the July Plot contains such a full explanation of this attempt on Hitler's life—in addition to a forensic analysis of the day, the book includes short biographies of the key characters involved, the first-person recollections of witnesses, and a "what if" section explaining the likely outcome of a successful assassination.

"An engaging history by a talented and accomplished writer." —Roger Moorhouse, author of Killing Hitler

The July Plot of 1944 was masterminded by Count Claus von Stauffenberg, a member of the German General Staff, who had been rushed back from Africa after losing his left eye and right hand. For his injuries, he had been decorated as a war hero. However, he'd never been a supporter of Nazi ideology—and he was increasingly attracted by the approaches of the German resistance movement.

After an attempt to assassinate Hitler in November 1943 failed, Stauffenberg developed a new plot to kill him at the Wolf's Lair, fortified underground bunkers, on July 20, 1944. Besides the führer's assassination, Stauffenberg organized plans to take over command of the German forces and sue for peace with the Allies. With the help of photographs, explanatory maps, and diagrams, author Nigel Jones dissects the events leading up to the attempt, the events of the day in minute-by-minute detail, and the aftermath in which the conspirators were hunted down. No other work on the July Plot contains such a full explanation of this attempt on Hitler's life—in addition to a forensic analysis of the day, the book includes short biographies of the key characters involved, the first-person recollections of witnesses, and a "what if" section explaining the likely outcome of a successful assassination.

"An engaging history by a talented and accomplished writer." —Roger Moorhouse, author of Killing Hitler

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Countdown to Valkyrie by Nigel Jones in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World War II. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

| 1 | A Good German The Early Life of Count Claus von Stauffenberg |

Jettingen, 15 November 1907: boy twins are born to Caroline, Countess von Stauffenberg, at one of the family’s several country properties in the province of Swabia in south-western Germany. Very unusually, this is the second set of male twins that the countess has borne her husband, Count Alfred von Stauffenberg, Lord Chamberlain to the king and queen of the small state of Württemberg. Just over two years before, on the Ides of March 1905, one year after their marriage, and on the anniversary of Julius Caesar’s assassination, she had presented her husband with another pair: Alexander and Berthold. As they grew up, Alexander would be merry and musical, but smaller in stature and academically less gifted than his brilliant twin. Berthold, whose salient physical feature was his luminous, penetrating eyes, would grow up closer to his younger brother Claus in their good looks, keen intellects and in their courageous, mystically chivalrous temperaments.

(Left to right) Countess Caroline Schenk von Stauffenberg with Alexander, Berthold and Claus, c.1910.

Sadly, of Countess Stauffenberg’s second set of twins, only one survived: Konrad died the day after his birth, but Claus grew to be the family’s favoured Benjamin: tall, dark and handsome, with a natural ease of manner and grace that charmed almost all those who entered his circle. The Stauffenbergs were a noble family who had lived among the rolling wooded hills of Swabia for centuries, and traced their ancient lineage, and family name – Schenk – back to the Middle Ages.

The first record of a Stauffenberg – the name derives from a long-vanished Swabian fortress on a conical hill near Hechingen – is of a certain ‘Hugo von Stophenberg’ in 1262. From 1382, the family can be traced in an unbroken line of descent. The Stauffenbergs followed professions suitable to their status: there were many soldiers, including warriors who served on Germany’s ever restive eastern borders with the Teutonic Knights or the Knights of St John. Other family members, however, showed more spiritual than temporal inclinations, and the family produced a number of clerics and university scholars. In Claus von Stauffenberg the two strains – worldly and mystic, military and ecclesiastic – united in one commanding, towering personality, just as he inherited his handyman father’s practical capability, alongside his mother’s contrasting dreamy literary tendencies.

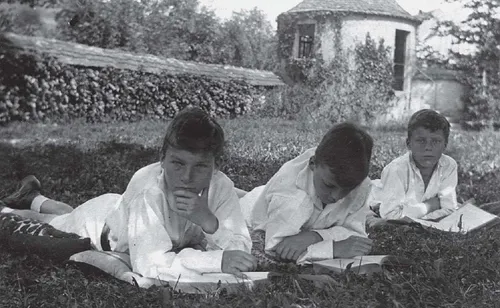

(Left to right) Alexander, Claus and Berthold in the garden of Lautlingen Castle, c.1918.

Alexander, Claus and Berthold in the Old Castle, Stuttgart.

In 1698 one Stauffenberg became a hereditary baron, and a century later in 1791, to reward the staunchly Catholic family’s loyalty to the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperors who reigned in Vienna, another Stauffenberg was promoted to become a hereditary imperial count (Graf). Claus von Stauffenberg’s title of count had been granted to his great-grandfather, Baron Franz von Stauffenberg, by Ludwig II, the unstable, castle-building king of Bavaria, in 1874. Over the centuries the family had acquired extensive estates on the borders of Bavaria and Swabia, including Claus’s birthplace, Jettingen, and the ‘castle’ (Schloss) – in reality a small manor house at Lautlingen in the ‘Swabian Alps’ hills – where the brothers would do much of their growing up. Their early childhood was spent at the Alte Schloss (Old Castle), an ancient royal residence in the heart of the Swabian capital Stuttgart, long the seat of their royal masters, the monarchs of Württemberg.

The boys’ father, Alfred, was appointed Lord Chamberlain in 1908, a year after Claus’s birth. Valued for his practical, no-nonsense skills in running the royal estates as well as his own – he was not above wallpapering a room, or taking the family gardens in hand personally – Alfred’s position gave his family the run of the royal residences and a familiarity with casually superior aristocratic ways that were to become second nature to them. The boys affected a casual, even eccentric style of dress that in Claus’s case would lead to charges of slovenliness when he joined the army. The attitude of not caring what others thought extended to the family table, where guests were astonished by their habit of communicating in growls and grunts rather than words, a private language they called ‘signalling’.

Family concert in Lautlingen: Berthold (with violin); Alexander (piano) and Claus (cello), 1917.

Countess Caroline was a complete contrast to her gruff, unsentimental husband, both in her background and in her unworldly, languorous character. Where he was a south German and Catholic in religion, she was a Lutheran Protestant from Germany’s harsh north-eastern coast. Born Caroline Üxküll-Gyllenbrand, she was descended from the notable soldier Field Marshal August von Gneisenau, who had galvanised Prussian resistance to Napoleon. Fluent in French and English, the countess loved art and the theatre, and enthused her three sons with her passion for literature and languages. All the boys were precocious learners, though their interests diverged: Alexander was silent, sedate and philosophical; Berthold fiercely intellectual and academic; while Claus was the fearless warrior: riding horses and scrambling up rocks from an early age. When confronted with a problem Claus always sought a solution, even if it was a ‘quick fix’. All three brothers loved the outdoor pursuits that came with their cultivation of the family estates: haymaking, riding, skiing and walking the high Alpine pastures came as easily to them as knocking on doors and running away did to city boys.

Lautlingen, 31 July 1914: the Stauffenberg family were enjoying their annual summer holidays at Schloss Lautlingen when the news came through that would disrupt their rural idyll – and that of the rest of Europe – forever. Germany was mobilising for war. Already, her forces were moving according to pre-arranged timetables, crowding onto trains carrying them across the Rhine into Belgium and France, an invasion that would bring Britain into the conflict, and turn a European struggle into the First World War. In the east huge Russian armies were moving into the Teutonic heartland of east Prussia – the area of the Masurian Lakes around Rastenburg that Claus von Stauffenberg would one day come to know all too well.

The following day, 1 August 1914, Countess von Stauffenberg decided to follow her husband back to the family apartments on the second floor of the Old Castle in Stuttgart. An air of excitement, even hysteria had swept over the nation. Even the sleepy Swabians, a people mocked by other Germans for their placid, cautious nature, were caught up in the prevailing excitement.

Within days came the first news of the fighting: on 13 August 1914 a cousin, Clemens von Stauffenberg, was reported killed; and on 28 August there was an air-raid alarm over Stuttgart. The boys were infected by the war: young Claus – just seven years old – dissolved into a flood of tears at the thought that the war would almost certainly be over before he was old enough to fight in it. All the brothers wrote poems hymning the successes of German arms; Berthold showed a particular interest in the Kaiser’s High Seas Fleet that would one day blossom into a naval career.

The Stauffenberg family felt the war’s depredations like all other Germans: in March 1917 Alfred von Hofacker, the boys’ cousin, fell at Verdun. Alfred’s brother Casar, a future close collaborator of Claus in the conspiracy against Hitler, was taken prisoner by the French in October 1918, and remained in captivity until 1920.

The British naval blockade bit hard, forcing Countess von Stauffenberg to abandon her regular tea stall at Stuttgart station for lack of supplies. In 1917 the boys shouldered scythes and went out into the fields around Lautlingen to help bring the harvest home in place of the men who were away at war. Caroline’s sister, Countess Alexandrine von Üxküll, head of the Württemberg Red Cross, returned from Russia after a nightmare nine-month journey by train and sledge to bring supplies and solace to German prisoners of war shivering in remote Siberian camps. She told tales of a vast country in the throes of revolution, where atrocities and spreading inhumanity were but a foretaste of the terrible decades to come.

Russia’s withdrawal from the war early in 1918 came too late to stave off Germany’s defeat. After the failure of the last-gasp German spring 1918 offensives in the west, the collapse came quickly. Squeezed by the blockade and subsisting on a diet largely composed of turnips and ersatz food, the working classes were in an angry, resentful mood, and ready to listen to the revolutionary message coming out of Russia. As German armies reeled back at the front, the country’s rulers asked for an armistice, only to find the spectre of red revolution stalking the Fatherland too.

Stuttgart, 9 November 1918: throughout German history 9 November is a date that recurs like a tolling bell. In 1989, it was the day that the Berlin Wall came down, reuniting the nation sundered by the Second World War. In 1938 as the storm clouds of that war gathered, it was the date of the infamous Reichskristallnacht – the most blatant display of the Hitler regime’s murderous hostility towards the Jews – when mobs inspired by the authorities had torched synagogues, trashed shops, looted property and beaten and arrested hundreds of Germany’s Jews in naked displays of toxic hate that shocked and horrified the world. In 1918, 9 November was the day when revolution engulfed Germany.

King Wilhelm II of Württemberg – not to be confused with Kaiser Wilhelm II of all Germany, whose abdication and flight to Holland occurred on this fateful day – had already given orders, as strikes and disorders erupted across even previously peaceful Swabia, that no one should attempt to defend Württemberg’s local monarchy with arms. The king had always enjoyed a cosy, typically Swabian intimacy with his subjects, and now, as always, he walked alone and unguarded through Stuttgart’s streets, despite the flying of red flags and noisy demonstrators calling for peace and revolution. At the request of his ministers, the king called an assembly to devise a new republican constitution. At 11 a.m., a mob invaded the royal palace, and Count Alfred von Stauffenberg was one of the loyal servants who prevented the intruders from gaining access to the royal apartments. Even so, a red flag was hoisted above the palace and the king – accompanied by Count Stauffenberg – left the city for his hunting lodge at Bebenhausen. Stauffenberg senior took charge of the subsequent negotiations between the king and the new republican authorities, and the monarch abdicated on 30 November.

Meanwhile, on 11 November 1918, the armistice ending the war had come into force. Claus von Stauffenberg spent his eleventh birthday on 15 November in tears; he had resented the king’s refusal to defend the monarchy by force, and did not want, he said, to ‘celebrate the saddest birthday in my short life’. During the next few months the Stauffenbergs, staying largely at Lautlingen while a new town flat in Stuttgart’s Jagerstrasse was prepared for them, experienced vicariously Germany’s chaotic political events.

A Communist revolution, spearheaded by the Spartacus League led by Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, was crushed by the paramilitary Freikorps – remnants of the old Imperial Army and young right-wing volunteers – employed by, but hostile to, the new Social Democratic government of Friedrich Ebert. The Spartacus rising in January 1919 in Berlin was bloodily suppressed, and Liebknecht and Luxemburg were murdered. In Germany’s second city, Munich, a ‘Soviet republic’ led at first by German anarchists, then by professional revolutionaries sent by Lenin, was similarly crushed by the Freikorps. This left Bavaria, Swabia’s neighbour, a happy hunting ground for right-wing extremists who found the atmosphere of the Bavarian capital more tolerant of their constant anti-republican conspiracies than ‘red’ Berlin.

Swabia was largely spared such disorders, and the Stauffenberg brothers continued their education at the Eberhard Ludwig Gymnasium, one of Stuttgart’s most prestigious schools. In their spare time the brothers often visited the theatre, though their father refused to set foot in Stuttgart’s former Royal Theatre since it had fallen into the hands of republicans. They relished the classic giants of the German stage – Goethe, Schiller and Hölderlin (the latter two were fellow Swabians) – and themselves acted in a production of Shakespeare’s tragedy about the assassination of a tyrant, Julius Caesar.

Also to their father’s disapproval, the brothers fell under the influence of Germany’s Jugendbewegung – the youth movement known as the Wandervogel (Wandering Birds). This had originated before the war in which many of its young members had sacrificed themselves, and was much given to long hikes through Germany’s fields and forests. At night the Wandervogel would camp out and recite poetry or strum songs on their guitars around the camp fire. Owing something to Britain’s Boy Scouts, and resembling the later Beatniks, the Wandervogel were generally nationalist in their political views, although some dabbled in idealistic socialist notions too. There was also a strong streak of mysticism in the movement, a semi-pantheist identification with the ‘soul’ of Germany. The group joined by the Stauffenbergs – the ‘New Pathfinders’ – were particularly influenced by the ideas of the poet Stefan George.

Now largely forgotten, George was then a hugely influential figure in Germany. An aloof, austere man who affected a late nineteenth-century ‘decadent’ artists’ style of dress – long hair, floppy beret, smock, with an expression of mocking disdain on his chiselled features – George was famous for his peripatetic lifestyle. Disdaining a permanent home, he travelled constantly to stay at the residences of his devoted young – and exclusively male – disciples. His privately published poetry was not widely known, but to the self-appointed elite who followed him, his verses were guiding stars.

Homosexual in tone, and heavy with portentous symbolism, George’s poetry prophesied the coming of a ‘New Reich’ (the title of one of his works). Like ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Prologue: High Summer in the Wolf’s Lair

- 1. A Good German: The Early Life of Count Claus von Stauffenberg

- 2. Seizing the State: The Irresistible Rise of Hitler’s Nazis

- 3. Rule of the Outlaws

- 4. Hitler’s March to War

- 5. Hitler’s War

- 6. Lone Wolf: Georg Elser and the Bomb in the Beerhall

- 7. The Devil’s Luck: Henning von Tresckow and the Army’s Plots against Hitler

- 8. Enter Stauffenberg: The Head, Heart and Hand of the Conspiracy

- 9. Valkyrie: 20 July 1944

- 10. Retribution: Hitler’s Revenge

- Afterword with Count Berthold Schenk von Stauffenberg

- Dramatis Personae

- Guide to Sites

- Acknowledgements and Sources