- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

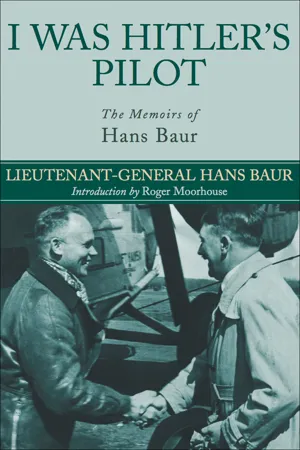

A chilling memoir by the man who flew the Führer.

A decorated First World War pilot, Hans Baur was one of the leading commercial aviators of the 1920s before being pitched into the thick of it as personal pilot to a certain "Herr Hitler." Hitler, who loathed flying, felt safe with Baur and would allow no one else to pilot him. As a result, an intimate relationship developed between the two men and it is this which gives these memoirs special significance. Hitler relaxed in Baur's company and talked freely of his plans and of his real opinions about his friends and allies.

Baur was also present during some of the most salient moments of the Third Reich; the Röhm Putsch, the advent of Eva Braun, Ribbentrop's journey to Moscow, the Bürgerbräukeller attempt on Hitler's life; and, when war came, he flew Hitler from front to front. He remained in Hitler's service right up to the final days in the Führerbunker. In a powerful account of Hitler's last hours, Baur describes his final discussions with Hitler before his suicide; and his last meeting with Magda Goebbels in the tortuous moments before she killed her children. Remarkably, throughout it all, Baur's loyalty to the Führer never wavered. His memoirs capture these events in all their fascinating and disturbing detail.

A decorated First World War pilot, Hans Baur was one of the leading commercial aviators of the 1920s before being pitched into the thick of it as personal pilot to a certain "Herr Hitler." Hitler, who loathed flying, felt safe with Baur and would allow no one else to pilot him. As a result, an intimate relationship developed between the two men and it is this which gives these memoirs special significance. Hitler relaxed in Baur's company and talked freely of his plans and of his real opinions about his friends and allies.

Baur was also present during some of the most salient moments of the Third Reich; the Röhm Putsch, the advent of Eva Braun, Ribbentrop's journey to Moscow, the Bürgerbräukeller attempt on Hitler's life; and, when war came, he flew Hitler from front to front. He remained in Hitler's service right up to the final days in the Führerbunker. In a powerful account of Hitler's last hours, Baur describes his final discussions with Hitler before his suicide; and his last meeting with Magda Goebbels in the tortuous moments before she killed her children. Remarkably, throughout it all, Baur's loyalty to the Führer never wavered. His memoirs capture these events in all their fascinating and disturbing detail.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access I Was Hitler's Pilot by Hans Baur in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

The First War in the Air

I WAS BORN in Ampfing near Mühldorf on the River Inn in southern Bavaria in the year 1897; but when I was only two years old my parents moved to Munich. I began my career as a commercial apprentice in Kempten, and but for the war I might have spent the rest of my life in an office.

I was seventeen when the First World War broke out. A wave of patriotic enthusiasm went through the country, sweeping me with it, and I volunteered for service. Too young and not big enough to carry a heavy pack, was the verdict. And this was what first turned my attention to the air – after all, airmen didn’t have to carry packs, so I decided to try my luck again, in the air this time. And to make quite certain my application would not get lost anywhere on the way I wrote direct to the Kaiser. I didn’t get a reply from the Kaiser, but a letter did come after a while from the air force depot at Schleissheim informing me that for the moment they needed no further recruits; if, however, at any time in the future . . .

That was in September 1915. I waited impatiently for about a month, and then I wrote to the Kaiser again. In due course another letter arrived from Schleissheim, and this time I was told to report on 25 November, which I did with tremendous enthusiasm, quite convinced that within a few weeks I should be in the air.

As a very raw recruit I was given two months’ training – but not in the air – and then posted to Bavarian Air Detachment 1B. When I arrived I was welcomed amiably enough, but my extreme youth induced a general ‘Germany’s last hope’ sort of atmosphere, which wasn’t very encouraging.

After several months in the office I asked my commanding officer whether I couldn’t put in a little time in the evenings with the planes – and with a grin he agreed. After that I was allowed to help the mechanics clean the engines. That wasn’t my idea at all, but at least I was actually nearer the planes than before. From time to time notices came in asking for volunteers for flying service, and as I was in the office I saw them first, so one day I approached my commanding officer again and asked him to let me volunteer. After a while he gave way, and sent me off to Verviens, where the volunteers were sifted. There were one hundred and thirty-six of us in all, and most of the others were big, strapping fellows who made me feel very small; many of them were already veterans with decorations. But to everybody’s surprise, four weeks later ‘Pioneer Hans Baur’ (that was my exalted rank) received instructions to report to the Air Training School at Milbersthofen.

I was already keenly interested in technical matters, and I had learned a good bit at Schleissheim, so I found it easy enough to reach the technical standard required. After that came actual flying training at Gersthofen, where we were formed into groups of six, each under an instructor. I was the first of my batch to take my solo test – after I had done only eighteen flights with an instructor; the usual number was between thirty-five and forty. So far we had learned only take-offs and landings, and now I enquired from a more advanced pupil how you spiralled – our instructor hadn’t told us anything about that.

When a pupil made his first solo flight no other machine was allowed in the air; everyone concentrated on the test, and it created quite a tense atmosphere. I did mine in an Albatross with a hundred-horsepower engine, a reliable trainer which did about seventy-five miles an hour. I felt calm and confident, and I took off without incident and went up to about two thousand five hundred feet. I had never been up so high before – not more than a thousand feet with the instructor. Then I shut off the engine and did exactly what the advanced pupil had told me. Turning left I spiralled round, and when I thought I was dipping a little too much I easily corrected it. It was all quite simple, and at about six hundred feet I flattened out, flew my obligatory round and then made a perfect landing.

My instructor was far more excited about it than I was, and he didn’t know what to do: dress me down or praise me, so he did both alternately. The second and third tests I did without the spiral, and with that I qualified. I was obviously cut out for a pilot. After that I was sent as an observer to an artillery training school (where they used live shells) to take the place of a pilot who had been killed in a crash. I was there six weeks, and after that my application to be posted once again to my old 1B was granted and I was back again on active service – and not in the office this time.

My first nine days in France were spent chasing my old comrades around, because they were constantly being transferred, but I caught up with them at last, and this time my reception by the old hands was enthusiastic. There was a particularly good reason for it, because I had been reported killed in a crash. The victim turned out to have been a comrade of the same name.

It was some days before the weather became fit for flying, but at last I was able to get into the air. It was a DFW, and I put it through its paces very thoroughly, trying out everything I had learned. When I came down to a perfect landing the ground personnel and the observers cheered, though the other pilots, mostly strangers to me, weren’t so enthusiastic. After that there was no shortage of observers anxious to go into the air with me, for an observer is completely dependent on his pilot.

A few days after that came the big German offensive, and I flew an armoured infantry-support machine. No less than five thousand guns had been massed, an unprecedented number for those days, and they put up a creeping barrage, which was probably our chief danger, for we naturally had to fly very low. Heavy mist made visibility poor, but from time to time we could see the trenches below. Our men were gathering in their advanced positions, but there was no sign of the French, and their front-line trenches were empty. No doubt the heavy barrage was keeping them in their dugouts.

After about three hours of flying backwards and forwards along the front line we flew over into French territory, and there we saw long columns of men, and horse-drawn carts and lorries. We decided to machine-gun and bomb them, our ‘bombs’ being hand-grenades in clusters of six. Our attack produced a panic; horses reared, carts overturned, and the column came to a halt in confusion. Of course, we were soon under heavy fire, and our wings were riddled. My engine was hit, too, and we had to get back behind our own lines, which we just succeeded in doing; but in landing I hit a telegraph pole, and the machine turned upside down. Fortunately my observer and I sustained only superficial injuries, but we had to tramp about twelve miles before we could find a telephone to let our squadron know what had happened to us. In addition to our accident, our squadron had lost two other planes and their crews.

After that I spent a few days at base and then returned to duty. This usually consisted of two and sometimes even three flights a day, each of between three and four hours, so we were kept busy. So far our machines had not been suitable for air combat, but now we were equipped with the Hannoveraner, the CL.3a, a small and reliable double-decker powered by a 185-horsepower Argus engine capable of a speed of over a hundred miles an hour, very fast for those days, and armed with two machine-guns, one fired by the pilot, the other by his observer. Up to the end of the war I shot down nine French planes, which was the top ace record for pilots flying artillery observation and infantry-support planes. But one of them gave me the fright of my life. We shot it down in poor visibility, and as it crashed we suddenly thought it was one of our own. Fortunately it turned out to be a French ‘Breque’, and we discovered that we had mistaken a black and white squadron marking on the plane’s rudder, for the familiar black and white German cross.

The war ended on 9 November. As Squadron-Leader I was instructed to take back my squadron from Sedan, where we were at the time, to Fürth in Bavaria. The weather was very poor, and visibility was low, but as far as I was concerned that wasn’t the trouble at all. We had machine-gun belts in a case between me and the engine, and the armourer had forgotten to chock them so that the munitions case didn’t slip. It did, and I could no longer control the plane properly. When I realised that I was losing height and practically out of control, I did my best to land, but we crashed. My observer was flung clear and came off with a few scratches, and French peasants who had been at work in the fields ran up and released me from the wreckage. We set fire to the plane and did the rest of the journey by car. But when we got to the old imperial city not one of the other planes had arrived. They had all been compelled to make forced landings on account of the weather.

PART TWO

The German Lufthansa

A PERIOD OF uncertainty and impatient waiting followed, for I didn’t know quite what to do, but on 15 January 1919, the first military air-mail service was founded, and out of five hundred Bavarian wartime pilots six were chosen – of whom I was one. The Entente Powers allowed us ten old Rumpler C.1s, each powered by a 150-horsepower engine and capable of just over ninety miles an hour – nothing extraordinary, but good enough to start with. Later on we were allowed a couple of Fokker D.7s, the last word in one-seater fighter planes. I was delighted to try them out, and this was the plane with which I first looped the loop.

These were the days of the revolution in Germany, with a Soviet Government in Fürth and another one in Munich, and for a time I served as a pilot with the Free Corps founded by Ritter von Epp; but things gradually settled down again. Soviet Governments – at least in Germany – became a thing of the past, and the great idea now was to earn a living. What other way was there for me but in the air?

By the terms of the Versailles Treaty, Germany was not allowed to manufacture planes, and the authorities had to obtain Entente permits for any they had in use. Such permits were not easy to get, even for civil airlines. For example, the Bavarian Luft-Lloyd was allowed four machines, and the Rumpler Air Line, which had its headquarters in Augsburg, the same number. The Rumpler planes maintained a service Augsburg – Munich – Fürth – Leipzig – Berlin.

I applied for a pilot’s job with the Bavarian Luft-Lloyd. On 26 October 1921, I received my civil air-pilot’s licence (Number 454) from the Reich Ministry of Transport and on 15 April 1922, I became a pilot for the Bavarian Luft-Lloyd in Munich. There were three of us in all: Kneer, Wimmer and myself, and even in 1922 we had only old wartime machines: three Rumpler C.1s and an Albatross B.2. The Rumplers were powered by Benz 150-horsepower engines, whilst the Albatross had a Mercedes 120-horsepower engine.

Before the official opening of the new line, Wimmer and I made a trial flight to Constance. We had been in the air about an hour when the engine began to knock. I advised Wimmer, who was piloting the plane, to land, but we disagreed about the cause of the trouble and he decided to fly on. We actually got as far as Friedrichshafen, but then there was a big bang and the cabin filled with smoke. My diagnosis had been right, but Wimmer managed to crash-land us. He was uninjured, but I got a nasty bang in the face. Unfortunately the plane, a Rumpler, was a total wreck, and this meant that we now had one machine less for the line, for in those days replacements were almost impossible to obtain.

However, with the three old machines we had left we did manage to run a fairly regular daily service to Constance, a distance of one hundred and twelve miles; a mere nothing nowadays, but with the machines we had, and against constant west winds, it was quite an achievement. Each of us had his turn of duty every third day. If we were unlucky we got the Albatross, an old training plane with a top speed of about seventy-five miles an hour – which meant that when we had to fly against headwinds of fifty or fifty-five miles an hour, which was often the case in the spring and autumn, we were really doing only about twenty or twenty-five miles an hour, so that five hours and more for the short journey was nothing unusual. But we couldn’t carry enough petrol with us for such flying times, and this meant that we had to make intermediate landings to tank up, which delayed us still further.

It sounds almost unbelievable now, and present-day airline pilots can have no conception of the difficulties we had to contend with. Our first passengers had to be tough, too, and I often felt sorry for them as they sat there wrapped up like Arctic explorers. There was no room in the plane even for what little luggage they were allowed to take, and it had to be strapped on outside, where it broke the airflow. In summer, though the flying time was shorter, the old engines would often lose oil, and headwinds would spray it back into the passengers’ faces. The windscreen was small and right in front, so that when we flew through rain and hail, as, of course, we often had to, the passengers got it full in their faces, and it was as though they were being scourged. Such experiences weren’t particularly good publicity, either, and very often a man who had chanced it once decided that he’d go by train next time. But we did our best for our passengers, and in the end . . .

Late in 1922 we obtained the first plane that was ever specifically built as a passenger-carrying machine. It was the Junkers F.13. It had a proper cabin with four passenger seats, and as there was a second seat beside the pilot – in those days we didn’t have mechanics with us – it could carry five passengers. In the following year, Junkers Luftverkehr took over our Bavarian Luft-Lloyd. Professor Junkers was aiming at a Trans-European Airline Union, and he succeeded in linking Switzerland, Hungary, Latvia, Estonia, Sweden and Austria with Germany into a really big network of air services.

Progress was fairly rapid now: new services to Vienna, Zürich and Berlin were opened, and, in addition, various special flights – for example, to the Passion Play in Oberammergau – were organised. This latter was very difficult, because although it was easy enough to find a place to land there, the take-off was a very different matter because of the soft, boggy ground. However, we managed it. We would take off from Munich at 07.00 hours and fly back again at 18.00 hours when the performance was over for the day.

It was on one of these flights that I had my first really prominent passenger: Nuntius Pacelli, the present Pope Pius XII. For his benefit I was instructed to make a detour on the way back to fly over the Zugspitze, because he was an enthusiastic mountaineer. It was perfect flying weather that day, and in the evening sunshine as we returned the view over the Alps was simply breath-taking in its beauty. The Nuntius was enthralled, and when we landed in Munich he shook hands with me and thanked me warmly for an unforgettable experience.

The lines from Munich to Vienna and Zürich were opened on 14 May 1923, and with this the first civil air-mail services were in operation. My colleague Kneer inaugurated the Zürich line, and I did the same for Vienna. Our high-ups and representatives of the Bavarian Government were present when we set off, for air transport history was about to be made.

From Munich I flew direct eastward by compass until I came to the Inn. From Linz I reached Traun, and there I picked up the Danube, and flew along it – which was just as well, because the weather had greatly deteriorated and visibility was poor. I made a safe landing on the airfield, thanks in part to an improvised landing cross which had been laid out for me.

A large crowd had assembled to greet us – I had two journalists and a third passenger with me – and we were welcomed by representatives of the Austrian Government and of the Austrian airline company, whilst many reporters and press photographers recorded the epoch-making event for posterity. The distance was two hundred and eighty-four miles, and we flew it in two hours and forty minutes.

I took off again at 13.00 hours for the return journey to Munich, where I landed safely, to be welcomed once again by a large crowd. The next day I flew the Munich – Zürich line, whilst my colleague Kneer took over the Vienna trip, and thenceforth we changed turn and turn about.

After a few weeks of this we began to have trouble with our engines, both with the 160-horsepower Mercedes and the 185-horsepower BMW. Neither of them was made to stand up to such constant use, and the number of engine-trouble emergency landings increased, though fortunately they all went off smoothly. Our directors made no difficulties when we had to break off a scheduled flight in this way, but they didn’t much care for it when there was any damage, for our machine park was still very inadequate. To encourage us to avoid damage they began to pay us accident-free bonuses for each trip.

As we had to reckon increasingly with engine-trouble, we spent most of our flying time keeping our eyes open for emergency landing sites; as soon as you had found and passed one you looked out for the next, until you happily landed at your destination – or had to use one of them. This naturally meant a greatly increased strain on us, but with care we managed to avoid trouble. Such forced landings were, of course, a great nuisance for our passengers, who had taken the plane in order to get to their destination quickly, and now perhaps found themselves in some remote village with no idea when they would finally arrive.

We had a good deal of trouble with headwinds, too, and they were very frequent on that line. On one occasion on the return journey it took me four hours to get to Linz, which isn’t even half-way to Munich – and I had a big-business man on board who had to get from Munich to Karlsruhe on important business. Instead of going on to Munich, we had to land in Wels to tank up, and by that time the weather was so bad I couldn’t take off. I told my passengers truthfully that it would be madness to fly in such weather, because the mountains would be invisible in the rain clouds. At that time, of course, instrument flying was unknown, and it would have meant flying low along the valleys, following the railway lines – and keeping a weather eye open for church steeples. But my passenger declared that unless he got to his destination in time he would be ruined; and he made such a song and dance about it that, against my better judgment, I agreed to make the attempt.

I managed to take off, and the flight to Munich along the railway line through the valleys was successful, and so was the landing. But the whole flight took over seven hours. He could have done it in nine by train. The next day we flew back to Vienna in two hours and ten minutes, a new record.

One day in Zürich my first crowned head came on board: King Boris of Bulgaria. He flew with me to Munich and on to Vienna, and went on from there by train, later I was to fly him to Hitler a good many times.

Our biggest difficulty was still with our engines, because Germany was as yet not allowed to manufacture any, but we finally obtained British Sidley Puma engines, and with these our troubles were over.

On 20 July 1923, we extended our lines down to the Balkans, and the connection from Vienna to Budapest was maintained by a Hungarian company using a Junkers F.13 on floats, a so-called hydroplane. Later on the service was carried on by flying-boats. The following year the line was extended from Zürich on to Geneva, so that we now had a really long air service Geneva – Zürich – Munich – Vienna – Budapest. The outline of the great network of air services which was later to cover Europe was already beginning to take shape, and the regularity of our flights and the absence of any serious accidents were gradually winning the general public over to air travel, which people were at first inclined to regard as foolhardy and dangerous.

But accidents were not always easy to avoid. I well remember what would have been a very bad one, but for the extra care I took because I happened to be flying Dr Schürff, an Austrian Cabinet Minister who was a great supporter of air travel. Although the machine had been overhauled, I decided to make a trial start from the hangar. For some reason the machine swung round to the right. I taxied back to the start and tried again – with the same result. And my efforts to correct the swing made it even more pronounced. Then I tried a ...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- PART ONE - The First War in the Air

- PART TWO - The German Lufthansa

- PART THREE - With Hitler Over Germany

- PART FOUR - The Second World War

- PART FIVE - In Russian Hands

- Index