- 480 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"A very impressive piece of work, and it is unlikely to be surpassed for many years . . . A very valuable guide to Napoleon's last great victory" (HistoryOfWar.org).

With this third volume, John Gill brings to a close his magisterial study of the war between Napoleonic France and Habsburg Austria. The account begins with both armies recuperating on the banks of the Danube. As they rest, important action was taking place elsewhere: Eugene won a crucial victory over Johann on the anniversary of Marengo, Prince Poniatowski's Poles outflanked another Austrian archduke along the Vistula, and Marmont drove an Austrian force out of Dalmatia to join Napoleon at Vienna. These campaigns set the stage for the titanic Battle of Wagram.

Second only in scale to the slaughter at Leipzig in 1813, Wagram saw more than 320,000 men and 900 guns locked in two days of fury that ended with an Austrian retreat. The defeat, however, was not complete: Napoleon had to force another engagement before Charles would accept a ceasefire. The battle of Znaim, its true importance often not acknowledged, brought an extended armistice that ended with a peace treaty signed in Vienna.

Gill uses an impressive array of sources in an engaging narrative covering both the politics of emperors and the privations and hardship common soldiers suffered in battle. Enriched with unique illustrations, forty maps, and extraordinary order-of-battle detail, this work concludes an unrivalled English-language study of Napoleon's last victory.

"Sheds new light on well-known stages in the battle . . . he has covered more than just an epochal battle in a magnificent book that will satisfy the most avid enthusiasts of Napoleonic era military history." — Foundation Napoleon

With this third volume, John Gill brings to a close his magisterial study of the war between Napoleonic France and Habsburg Austria. The account begins with both armies recuperating on the banks of the Danube. As they rest, important action was taking place elsewhere: Eugene won a crucial victory over Johann on the anniversary of Marengo, Prince Poniatowski's Poles outflanked another Austrian archduke along the Vistula, and Marmont drove an Austrian force out of Dalmatia to join Napoleon at Vienna. These campaigns set the stage for the titanic Battle of Wagram.

Second only in scale to the slaughter at Leipzig in 1813, Wagram saw more than 320,000 men and 900 guns locked in two days of fury that ended with an Austrian retreat. The defeat, however, was not complete: Napoleon had to force another engagement before Charles would accept a ceasefire. The battle of Znaim, its true importance often not acknowledged, brought an extended armistice that ended with a peace treaty signed in Vienna.

Gill uses an impressive array of sources in an engaging narrative covering both the politics of emperors and the privations and hardship common soldiers suffered in battle. Enriched with unique illustrations, forty maps, and extraordinary order-of-battle detail, this work concludes an unrivalled English-language study of Napoleon's last victory.

"Sheds new light on well-known stages in the battle . . . he has covered more than just an epochal battle in a magnificent book that will satisfy the most avid enthusiasts of Napoleonic era military history." — Foundation Napoleon

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Napoleon's Defeat of the Habsburgs Volume III by John H. Gill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 19th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Clearing the Strategic Flanks

CHAPTER 1

War Along the Vistula

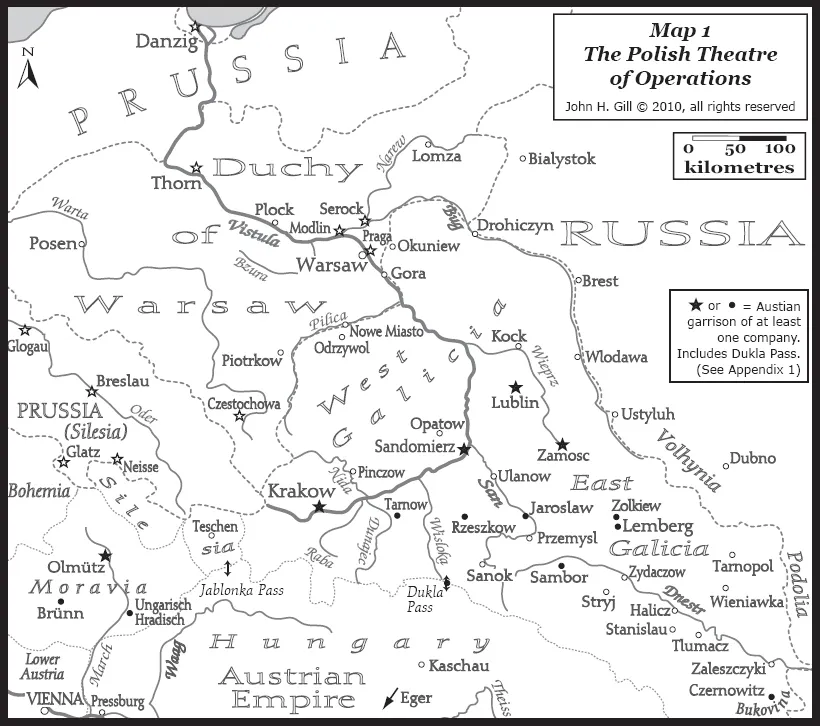

Poland was the second most important theatre of operations in the initial stages of Austrian planning for war in 1809.1 Although it had slipped to third place in March as Italy assumed greater prominence, Poland remained a key element in Austria’s strategy, from both a military and a political standpoint. On the military side, a Habsburg invasion force was to ‘drive on Warsaw with overwhelming strength’, knocking the Poles out of the war and thus removing a potential threat to the Austrian strategic rear before turning west to join the Hauptarmee in central Germany.2 Politically, Vienna hoped to purchase Prussia’s participation in the conflict by offering King Friedrich Wilhelm III captured Polish territory, including Warsaw. It was further hoped that the Austrian advance would drive Polish troops onto Prussian lands, provoking a confrontation and perhaps forcing the reluctant Prussian monarch to ally himself with Austria.3 Alternatively, parts of Poland might be offered to the tsar to keep Russia out of the war. Finally, a resounding Habsburg victory could be expected to dampen any insurrectionary thinking among the discontented ethnic Poles of Austrian Galicia. With these goals in mind, Charles’s instructions to GdK Archduke Ferdinand Karl Josef d’Este, the commander of VII Corps, stressed speed, surprise, and the importance of making an impression on ‘public opinion’. Apparently concerned that Ferdinand would dissipate his strength by making unnecessary detachments, the Generalissimus enjoined him to keep his force together and to conduct his operations ‘with such vigour that nothing can resist you; the enemy’s embarrassment must be exploited and he must be left no time to recover until Your Grace is assured of his harmlessness.’4 These words, written on 28 March, resonate with irony, given the debilities that the Main Army would display in precisely these areas during the campaign in Bavaria.

Ferdinand, his family displaced from northern Italy, was fired by a sense of injustice and had been a passionate proponent of war with France, earning the nickname ‘war trumpet’ for his determined advocacy.5 He was approaching his twenty-eighth birthday in April 1809 and had previously participated in combat during the 1799 and 1800 campaigns in Germany with varying fortunes, including the cataclysm at Hohenlinden. In 1805, newly promoted to General der Kavallerie, he had been the nominal commander of the Habsburg army that invaded Bavaria, but escaped the ignominy of capture by fleeing to Bohemia before the surrender at Ulm. He later had the better of Wrede in a series of minor engagements near Iglau.6 Young, ambitious, and sure of himself, his desire for military glory may have been further piqued, as Pelet suggests, by the residual taint of the flight from Ulm (deserved or not).7 He certainly regarded the Poles as second-rate foes who would be easily vanquished, and he looked forward to taking his corps west to engage the ‘real’ enemy in the principal theatre of operations.8 This corps, with some 24,040 infantry and 5,750 cavalry, was structured like its fellows within the Hauptarmee but, owing to its independent mission and the open terrain in which it was to operate, it had twice as much light horse (four instead of two regiments) and its own miniature cavalry reserve of two cuirassier regiments.9 It was also assigned a large artillery component of ninety-four guns, though only seventy-six of these were on hand at the start of hostilities. In general, VII Corps was superior to its Polish adversaries in training and experience, but some infantry regiments had a high proportion of brand-new inductees and several were recruited wholly or partially from ethnic Poles of Galicia.10 Many of these men were unwilling subjects of the Habsburg crown and clearly preferred the cause of independence espoused by their brothers in the Duchy of Warsaw. Their sympathies and restiveness demanded special vigilance on the part of their commanders and in several instances led to serious desertion problems. In addition to Ferdinand’s field formations, approximately 7,600 to 8,000 men were available to defend Austrian Galicia in the army’s rear. This small force, under the orders of FML Fürst Friedrich Carl Wilhelm Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen, was composed almost entirely of depot troops—raw recruits who were only beginning to learn how to handle their muskets and manoeuvre in formation. Further second-line forces (ten Landwehr battalions) were designated to garrison Krakow, a critical supply base and fortress guarding the entry to Moravia.

Though the Austrians enjoyed broad advantages in training, experience, and numbers, VII Corps lacked a bridging train.11 This would prove a serious deficiency in a theatre dominated by the broad Vistula and intersected by numerous smaller watercourses. Given that Sandomierz was the only fortified crossing over the Vistula between Krakow and Warsaw, ‘prudence commanded him [Ferdinand] to make himself master of the Vistula,’ as Polish Captain Roman Soltyk noted in his history of the war.12 A secure crossing site with fortified bridgeheads on both banks could have been constructed before the war (albeit at the risk of provocation) as ‘a pivot for his operations’, to permit VII Corps to operate either west or east of the great river with equal facility.13 Instead, Ferdinand, with no bridging equipment, found his operations confined to the western (left) bank and he only gave thought to a suitably sited and protected crossing after his opening moves had failed to produce a decisive result. For contemporaries, the triangle of Polish fortifications at Modlin, Serock, and Praga was also critical; a later observer calls them ‘the strategic core’ of the duchy, locations where the Poles could recruit, train, and, if necessary, recuperate in relative safety.14 Soltyk notes that Ferdinand lacked a siege train that might have allowed him to reduce these key points and others (such as Thorn), but such an encumbrance would have been inconsistent with the need for rapid operations.15 Furthermore, as Ferdinand did not expect serious resistance from the Poles, he did not see this lacuna as a serious matter. Indeed, he founded his strategic thinking on the assumption that the Prussians would soon join the war and mop up Polish remnants while VII Corps marched west. This notion of imminent Prussian intervention on Austria’s behalf— inspired in part by the steady correspondence he maintained with Oberst Graf Goetzen, the pro-war governor of Prussian Silesia—seems to have evolved into a firm conviction in the archduke’s mind, an illusion that would guide his actions in the coming weeks.16

On the other side of the border, the Polish army commanded by GD Prince Joseph Poniatowski was inferior to the Austrian field force in almost every respect. The disparity in numbers was especially glaring. Where Ferdinand rode at the head of 29,800 men with seventy-six guns initially (rising to ninety-four), Poniatowski had barely 14,200 men and forty-one pieces on hand at the opening of the war. This figure included a small contingent of Saxon troops who, when the war broke out, were already under orders to return to their kingdom. Apart from the Saxons, this was largely a new army as far as its soldiery was concerned, having only come into existence in the latter stages of the 1806–7 war. Additionally, it was in the middle of a major reorganisation as third battalions were being created for each infantry regiment and company strength was expanding from 95 to 140 men to conform to the French model. Beyond the small field army, Polish troops constituted major portions of the garrisons in Danzig, Stettin, and Küstrin, a requirement that deprived Poniatowski of three infantry regiments (5th, 10th, and 11th) and the 4th Chasseurs. A few of these units, along with thousands of new conscripts and volunteers, would be drawn into the fighting in Poland during the course of the conflict, and men of the 4th Chasseurs would find themselves in action against German insurgents. Furthermore, three of the duchy’s infantry regiments (4th, 7th, and 9th)— one-quarter of its foot soldiers—were committed to the French adventure in Spain. These deductions left Poniatowski with a mere five regiments of Polish infantry, five of cavalry, and his Saxon contingent of two battalions and two hussar squadrons in the Warsaw area when the Austrians crossed the border. The only immediate reinforcement he could expect was the 12th Infantry in Thorn, which would hardly compensate for the impending loss of the Saxons. The Polish leadership, however, counted on nationalistic enthusiasm to increase the power and endurance of their forces. With a vision of national liberation as inspiration, they hoped to foment rebellion in Habsburg territory, raise the countryside against any Austrian invasion, and field large numbers of new formations once the campaign began.

Compared with their troops, many of the Polish generals and senior officers had amassed considerable combat experience fighting under French banners or in battle with Russia and Prussia since the early 1790s. The two most tested, competent, and popular—GD Jan Henryk Dabrowski and GD Joseph Zajaczek—however, thoroughly detested one another, and neither had much use for Poniatowski. These and other intrigues and suspicions at the top levels of the army cancelled out much of the experience that these men and their subordinates had accrued over the years and created fissures that had the potential to compound the army’s other problems.17 Moreover, the prince, 46 years old in 1809, was the son of an Austrian general and had himself served as a Habsburg officer for several years. Poniatowski had demonstrated courage, coolness, a talent for light cavalry operations, and an abiding interest in training in the course of his military apprenticeship, but this personal history left him vulnerable to malicious innuendo about confused loyalties and lingering pro-Austrian sympathies. Ferdinand certainly thought there were Habsburg attachments to exploit.18 After leaving Habsburg service, Poniatowski was placed—more or less against his will—in command of large Polish forces during 1792 and 1794. He had not shone, so his military competence also came into question, but Napoleon had appointed him as minister of war and de facto army commander when the duchy was established in ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Maps and Tables

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Conventions

- Table of Comparative Military Ranks and German Noble Titles

- Prologue

- Part I: Clearing the Strategic Flanks

- Part II: Wagram, Znaim, and Peace

- Epilogue

- Appendices

- Abbreviations

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Errata