- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

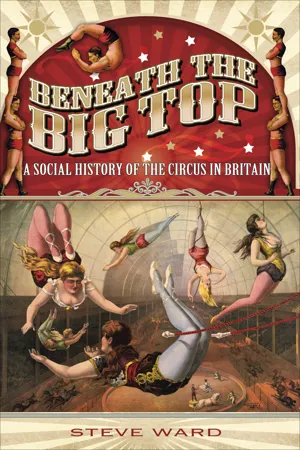

About this book

"A valuable and illuminating read, shedding a lot of light on the political, economic and technological factors that have driven circus evolution" (

The Circus Diaries).

Beneath the Big Top is a social history of the circus, from its ancient roots to the rise of the "modern" tented travelling shows. A performer and founder of a circus group, Steve Ward draws on eyewitness accounts and contemporary interviews to explore the triumphs and disasters of the circus world. He reveals the stories beneath the big top during the golden age of the circus and the lives of circus folk, which were equally colorful outside the ring:

• Pablo Fanque, Britain's first black circus proprietor

• The Chipperfield dynasty, who started out in 1684 on the frozen Thames

• Katie Sandwina, world's strongest woman and part-time crime-fighter

• The Sylvain brothers, who fell in love with the same woman in the ring

"As a former circus performer and now teacher and circus professional I thoroughly enjoyed this book!! The Circus has such a rich history and Steve does an amazing job at not only chronicling it but also telling entertaining and wonderful stories throughout. The photos are also amazing!! I recommend this book for both circus professionals and also for everyone else . . . it is a fabulous read for all!!" —Carrie Heller, Circus Arts Institute (Atlanta, GA)

Beneath the Big Top is a social history of the circus, from its ancient roots to the rise of the "modern" tented travelling shows. A performer and founder of a circus group, Steve Ward draws on eyewitness accounts and contemporary interviews to explore the triumphs and disasters of the circus world. He reveals the stories beneath the big top during the golden age of the circus and the lives of circus folk, which were equally colorful outside the ring:

• Pablo Fanque, Britain's first black circus proprietor

• The Chipperfield dynasty, who started out in 1684 on the frozen Thames

• Katie Sandwina, world's strongest woman and part-time crime-fighter

• The Sylvain brothers, who fell in love with the same woman in the ring

"As a former circus performer and now teacher and circus professional I thoroughly enjoyed this book!! The Circus has such a rich history and Steve does an amazing job at not only chronicling it but also telling entertaining and wonderful stories throughout. The photos are also amazing!! I recommend this book for both circus professionals and also for everyone else . . . it is a fabulous read for all!!" —Carrie Heller, Circus Arts Institute (Atlanta, GA)

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

From Ancient Roots to the Restoration: The Circus Survives

The sun beats down on the central courtyard in the Palace of Knossos in Crete. It is early afternoon and the crowd, in holiday mood, has been gathering since morning, thronging the Royal Road from the nearby port of Heraklion up towards the palace. Latecomers, pushing through the central gateway, jostle for position with the already eager spectators settled around the edge of the courtyard, as the crowd murmurs in anticipation. The courtyard, covering a space roughly equal to that of half the area of a football pitch, is surrounded by the whitewashed walls of the palace, decorated with brightly coloured frescoes; reds, blues and yellows all reflecting in the bright sun.

Then the rumbling of the crowd swells as, through one of the gateways, the acrobats enter – young men and boys stripped bare to the waist. They acknowledge the crowd as they parade around, waving and smiling, and then turn to face a gateway at the far end of the courtyard. A door swings open and the crowd roars as into the arena explodes a bull; wild-eyed and snorting, it twists and turns in confusion. Gradually the bull settles and the acrobats step forward.

Youths leaping over a bull c.1,500 BC. Scene from a fresco originally in the Palace of Knossos Crete, now in the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion. (Photograph by the author)

One, a tall, bronzed young man, moves towards the bull and the crowd holds its breath as the bull fixes its eyes upon the man. It paws the ground, creating a small cloud of dust as slowly it tosses its head and begins its charge. The young man stands his ground fearlessly as the bull approaches until, at the last moment as the bull lowers it horns, he leaps forward in a graceful swallow dive. Passing clean between the horns of the bull and placing his hands on the animal’s back, he somersaults to the ground. The crowd roars its approval. In a swirl of dust the bull turns in bewilderment as another youngster steps up. The bull charges towards him and this time the acrobat grasps the horns and uses them as a lever to assist his somersault over the beast. The crowd roars again and the spectacle continues, the acrobats making a fearless variety of somersaults over the charging animal.

This was a scene played out some 2,000 years ago in ancient Crete. Using contemporary fresco paintings, jewellery, pottery and other artefacts, the eminent archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans put forward the idea that ‘bull leaping’ was a regular occurrence in the Minoan culture. But what has it to do with the history of the circus?

If, for a moment, we strip away the artistry of the performer, then circus is very much an exhibition of physical skill, courage and mastery. The acrobat in the circus ring displays an obvious physical skill and courage, but also a mastery over the natural force of gravity; the animal trainer displays skill, courage and mastery over the animal. Circus at its basic level is a spectacle and as such, according to A. Coxe in the 1951 work, A Seat at the Circus, demands that, ‘Man, brought face to face with either events or other men, should react to them … there must be something physical about a spectacle; boxing is a spectacle, chess is not’. Presented before an audience this spectacle may take the form of entertainment, ritual or ceremony.

And that is just what the ‘bull leaping’ of Knossos was – a spectacle. Circus at its basic level and ‘bull leaping’ still continues today in the town of Mont de Marsan in the Gascony region of France, where brightly clad sauteurs (leapers) take part in the Course Landaise. This interaction between man and animal as an entertainment is not so far removed from the equestrian acts of the modern circus. As one 91-year-old lady commented on her childhood visit to the circus, ‘I liked the bareback riding and the girls who jumped on and off the horses and did pirouettes on their backs. It was all very clever, I thought’.

It is not just the Minoan culture that shows us physical ‘circus’ activities being presented. A wall painting in the fifteenth tomb at Beni Hassan in Egypt depicts both women jugglers and acrobats and dates from around 1900 BC. A century earlier, also in Egypt, the young Pharaoh Pepi gave the first recorded performance of a clown. He wrote, ‘He is a divine spirit – something to rejoice and delight the heart’. In the ancient Greece of 700 BC, wandering clown figures known as deikeloktas were seen in Sparta. Meanwhile, in China the tradition of circus goes back some 4,000 years and is steeped in symbolism. For example, the plates used in the skilful plate spinning acts symbolise the sun, and the performer is the intermediary between the people and the sun.

The Circus Neronius in Rome: an oval structure providing a space for chariot races and other spectacles. (Library of Congress)

Some scholars have traced the origins of the circus only as far back as the Roman Empire and the Circus Maximus in Rome. The Circus Maximus was an oval-shaped structure in which chariot races and other large-scale spectacles were held, frequently of a barbaric nature, often with the slaughter of both men and animals. Certainly the slaughter of man and beast as witnessed in the Circus Maximus was physical, yet the physicality of circus is predetermined. Every move is meticulously prearranged and choreographed, unlike the events of the Circus Maximus.

Other, more recognisably traditional, physical circus skills were presented during the Roman period. In Dinner with Trimalchio (part of Petronius’ Satyricon), Petronius writes about acrobats arriving at a dinner party. He goes on to say that acrobats are a common sight at the circus but hardly the sort of people to have at a dinner party, though the host Trimalchio seems to think that these acrobats are artistic. In his writing, Petronius not only describes in reasonable detail an act that would not be amiss in a present day circus performance but actually uses the phrase ‘at the circus’. From this we can assume that such acts of physical skill were common within the Roman period and presented in a specific dedicated performance space. The sixth century Roman historian Procopius gives a portrait of the Empress Theodora, who was trained as an infant in the arts of the stage and the ‘floor show’.

As the Roman Empire spread its tentacles across the world it transported much of its culture with it, even to the far-flung outpost of Britain. Large Roman amphitheatres have been excavated at St Albans and at Chester and, as it has been recorded that acrobats and jugglers were used as a ‘warm up’ to main events in the amphitheatre, it is logical to assume that Romans settling in Britain and other European countries would have enjoyed similar entertainments to those at home in Rome: gladiatorial combat, theatre, dance and acrobats, jugglers and other such amusements. Whereas we might recognise these skills described by Petronius as being a ‘circus style’ entertainment, the only connection between our modern circus and the Circus Maximus of Rome lies in name only.

With the decline of the Roman Empire in the fifth century AD, Britain entered a period very often referred to as the ‘Dark Ages’. Over the next 500 years, until the Norman invasion, Britain saw an influx of differing Germanic and Nordic tribes, each with their own distinct culture. Each had its own tradition of individual entertainers, sometimes retained by a nobleman, sometimes itinerant. These entertainers – frequently referred to as a scop and accompanied very often by a harp – were skilled at recitation, story telling, music and singing. From these traditions emerged the character of the jongleur.

The figure of the jongleur appeared somewhere between the ninth and tenth centuries. He was much more of an all-round performer and very often assisted minstrels and troubadours with displays of physical skills – skills that we would recognise today in a circus performance. It is significant that the French word jongleur is derived from jogleur, the word for a juggler, which in itself is derived from the Latin ioculator or joker. A jongleur was very often skilled in music, poetry, singing, juggling, acrobatics, dancing, fire eating, conjuring and presenting animals, as well as buffoonery. One unidentified jongleur is referred to by G. Speaight (1980), who writes about, ‘his ability to sing a song well, to make tales to please young ladies, and to be able to play the gallant for them if necessary. He could throw knives into the air and catch them without cutting his fingers and could jump rope most extraordinary and amusing. He could balance chairs and make tables dance; could somersault and walk doing a handstand’.

Medieval jugglers (one male, the other female) perform together. (Library of Congress)

One can imagine the scene in the great manorial halls of the early medieval period. There in the smoky and gloomy interior, lit only by candle or torchlight, with the lord of the manor and his entourage seated at the top table and the lesser beings seated along each side, stands our lonely jongleur. He begins by singing a well-known song before ending this with a back flip. The lord is amused and claps in appreciation. Those seated around him follow suit.

Encouraged by this, our jongleur then takes up some knives from a nearby table and he begins to juggle; first three, then four and maybe even five, to the delight and astonishment of his audience. And so he runs through his routine, each new skill meeting with much approval, until he completes his act by blowing a huge plume of fire into the air. He is pleased with his performance, the audience is pleased and, above all, the lord of the manor is pleased. Our jongleur can eat tonight!

However, jongleurs were not always seen in the best light. The fourteenth century Italian poet Petrarch referred to jongleurs as ‘people of no great wit and impudent beyond measure’. But if this was the case for the jongleur, then there was another type of performer who attracted even less respect – the gleeman. Whereas the jongleur often performed for noblemen, gleemen were distinctly individual itinerant performers who plied their trade at fairs, festivals and celebrations. Although often as individually skilled as the jongleurs, as entertainers they were considered the lowest of the low. Already, even at this early stage in history, the travelling performer was considered an ‘undesirable’ character; someone on the fringe of society who was not to be trusted.

The jongleur is not to be confused with the minstrel and the troubadour, whose main respective functions were to play music and sing, and to recite lyrical and romantic poetry. Minstrels were predominantly musicians and singers of poetry. Of French origin, from the eleventh century they were initially retainers at court and employed to entertain their masters’ guests with music and song. Many became proficient on the instruments of that period – the fiddle, the cittern, the bagpipes and the flageolet.

As courts grew more and more sophisticated, so minstrels were replaced by troubadours, who were usually educated men (and sometimes women), and who composed their own lyrical poetry based around the themes of chivalry and courtly love. Often troubadours recited their poetry to a musical accompaniment. As troubadours replaced minstrels, so minstrels became more itinerant and very often the troubadours would attack the jongleurs and minstrels in their poetry.

To maintain a degree of professionalism and quality, King Edward IV ordered in 1469 that all jongleurs should join a guild under his patronage, namely the Guild of Royal Minstrels, thereby placing all minstrels, troubadours and jongleurs under one banner. A guild was a form of professional organisation of the time. A jongleur had to join this guild or else cease performing, although many probably continued to do so illegally. Over 100 years before this, the minstrels of Paris had also been formed into a guild with the same rule. During the medieval period itinerant performers, once perceived as being on the fringe of society, were now being endorsed and given respectability through royal patronage.

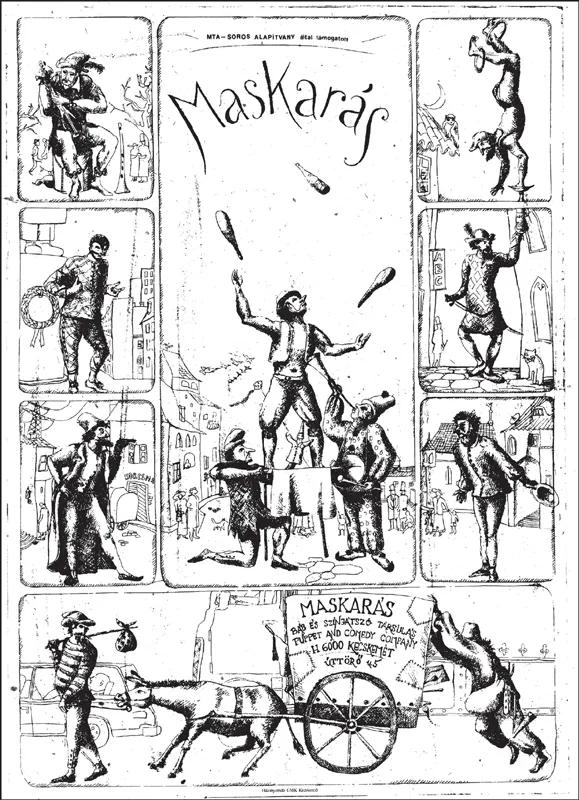

A poster for the company Maskarás, who base their performances upon medieval-style entertainments. (Author’s collection)

The character of the jongleur has also appeared in literature. In 1892, Anatole France wrote the story, ‘Le Jongleur de Notre Dame’, which, in turn, was based upon a thirteenth century medieval legend by Gautier de Coincy. Jules Massanet later adapted the story for the stage in 1902 and produced it as an opera in three acts under the same name. In the story a poor juggler becomes a monk and he has no gift to offer to the statue of the Virgin Mary except his skill. Because of this he is accused of heresy but the statue comes to life and blesses him.

Whilst the role of the jongleur continued throughout medieval times, another figure also developed: the jester. Familiar to many of us, he appears on playing cards in his multicoloured clothing, with bells dangling from his fool’s hat and clutching a stick with a pig’s bladder attached to it. This colourful portrayal of a jester is very much derived from the image of an Elizabethan jester, as described much later by Francis Douce in 1807.

‘The King’s Fool’: A modern interpretation of the court jester, carrying his sceptre topped with a fool’s head. (Library of Congress)

According to Douce, the jester’s coat was parti-coloured, with bells at the skirt and elbow. The hose sometimes had legs of contrasting colours. The hood, resembling a monk’s cowl, fell down over the head and shoulders and was sometimes decorated with asses’ ears or cockscomb. The jester carried an official sceptre or bauble, a short stick ending in a fool’s head or perhaps, a doll or puppet. Also sometimes attached was a pig’s bladder, with which the jester beat those who had offended him. The seventeenth century Flemish artist, Jacob Jordaens, portrayed the figure of the fool in several of his works. In Merry Company on a Terrace, the fool can be seen in the background holding aloft his sceptre with a fool’s head on it. In the works Folly and Cleopatra and Fool, the figure is shown in a monk-like cowl, to which are attached bells.

Jesters came from a wide variety of backgrounds; some from simple peasant stock, others from the world of clerics, and even from universities. Some were retained at court whilst others, the greater number by far, were itinerant but there was always the chance of being spotted by a nobleman and moved to higher circles. At a time when social mobility was very constrained and farm...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 From Ancient Roots to the Restoration: The Circus Survives

- Chapter 2 Acrobats, Ale and Aristocrats: The Eighteenth Century Age of Decadence

- Chapter 3 Clowns, Competition and Conflagrations: The Circus is Born!

- Chapter 4 The Queen and the ‘Lion King’: The Rise of the Nineteenth Century Menageries

- Chapter 5 Spectacles, Disasters and Murder: The Victorian Circus

- Chapter 6 Railways and Rings: The Circus in Nineteenth Century America

- Chapter 7 Magic, Movies and Music Halls: Stiff Competition for the Late Nineteenth Century British Circus

- Chapter 8 The Circus Goes to War: 1900–1919

- Chapter 9 Decades of Depression: The Circus Between the Wars

- Chapter 10 Fighting for Survival: The 1940s–1960s

- Chapter 11 And So the Wheel Turns: The Circus from 1970 to the Present

- Select Bibliography

- Sources on the British Circus Industry

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Beneath the Big Top by Steve Ward in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.